The University of Wisconsin-Eau Claire Tejano

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

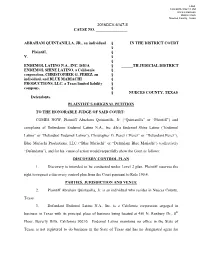

ABRAHAM QUINTANILLA, JR., an Individual § in the DISTRICT COURT § Plaintiff, § V

Filed 12/2/2016 3:52:11 PM Anne Lorentzen District Clerk Nueces County, Texas 2016DCV-6147-E CAUSE NO. ________________ ABRAHAM QUINTANILLA, JR., an individual § IN THE DISTRICT COURT § Plaintiff, § V. § § ENDEMOL LATINO N.A., INC. D/B/A § ______TH JUDICIAL DISTRICT ENDEMOL SHINE LATINO, a California § corporation, CHRISTOPHER G. PEREZ, an § individual, and BLUE MARIACHI § PRODUCTIONS, LLC, a Texas limited liability § company, § § NUECES COUNTY, TEXAS Defendants. PLAINTIFF’S ORIGINAL PETITION TO THE HONORABLE JUDGE OF SAID COURT: COMES NOW, Plaintiff Abraham Quintanilla, Jr. (“Quintanilla” or “Plaintiff”) and complains of Defendants Endemol Latino N.A., Inc. d/b/a Endemol Shine Latino (“Endemol Latino” or “Defendant Endemol Latino”), Christopher G. Perez (“Perez” or “Defendant Perez”), Blue Mariachi Productions, LLC (“Blue Mariachi” or “Defendant Blue Mariachi”) (collectively “Defendants”), and for his cause of action would respectfully show the Court as follows: DISCOVERY CONTROL PLAN 1. Discovery is intended to be conducted under Level 2 plan. Plaintiff reserves the right to request a discovery control plan from the Court pursuant to Rule 190.4. PARTIES, JURISDICTION AND VENUE 2. Plaintiff Abraham Quintanilla, Jr. is an individual who resides in Nueces County, Texas. 3. Defendant Endemol Latino N.A., Inc. is a California corporation engaged in business in Texas with its principal place of business being located at 450 N. Roxbury Dr., 8th Floor, Beverly Hills, California 90210. Endemol Latino maintains no office in the State of Texas, is not registered to do business in the State of Texas and has no designated agent for service of process in the State of Texas. -

La Frontera- the US Border Reflected in the Cinematic Lens David R

1 La Frontera- The U.S. Border Reflected in the Cinematic Lens David R. Maciel1 Introduction The U.S.-Mexico border/la frontera has the distinction of being the only place in the world where a highly developed country and a developing one meet and interact.2 This is an area of historical conflict, convergence, conflict, dependency, and interdependency, all types of transboundary links, as well as a society of astounding complexity and an evolving and extraordinarily rich culture. Distinct border styles of music, literature, art, media, and certainly visual practices have flourished in the region. Several of the most important cultural and artistic-oriented institutions, such as universities, research institutes, community centers, and museums are found in the border states of both countries. Beginning in the late 19th century and all the way to the present certain journalists, writers and visual artists have presented a distorted vision of the U.S. - Mexican border. The borderlands have been portrayed mostly as a lawless, rugged, and perilous area populated by settlers who sought a new life in the last frontier, but also criminals and crime fighters whose deeds became legendary. As Gordon W. Allport stated: 1 Emeritus Professor, University of New Mexico. Currently is Adjunct Professor at the Centro de Investigación y Docencia Económicas (CIDE) in Mexico City. 2 Paul Ganster and Alan Sweedler. The United States-Mexico Border Region: Implications for U.S. Security. Claremont CA: The Keck Center for International Strategic Studies, 1988. 2 [Stereotypes] aid people in simplifying their categories; they justify hostility; sometimes they serve as projection screens for our personal conflict. -

Selena Y Los Dinos

Case Study CX005.1 Last revised: February 24, 2014 Selena y los Dinos Justin Ward Selena Quintanilla-Perez was born in Texas on April 16, 1971 into an English-speaking Latino family of Jehovah’s Witnesses.1 Her father, Abraham Quintanilla, Jr. (“Quintanilla”) was an enterprising man who had spent his youth trying to make it in the Texas music scene as manager and member of a band called Los Dinos. Quintanilla took a job at a chemical plant when he settled down, but later left to open his own restaurant. During his (ultimately unsuccessful) effort to keep the struggling business afloat, he had the musically talented nine- year-old Selena perform live music to help attract customers. Although the restaurant failed, Selena continued to perform under the name Selena y los Dinos. She learned to sing in Spanish and began recording with local producers. After the eighth grade, she dropped out of school to pursue her musical career. The band remained in many ways a family affair: Quintanilla (once described as “the ultimate stage father”2) managed the group, her brother A.B. played bass guitar and wrote many of Selena’s songs, and she married the band’s guitarist, Chris Perez. By 1993, Selena was an award-winning Tejano singer and a rising star, having signed a record deal with Capitol/EMI (which had asked Selena to release albums as “Selena,” not “Selena y los Dinos”). She would go on to further musical success and to open a chain of boutique stores called Selena Etc. On February 7, 1993, Selena y los Dinos gave a free concert at Corpus Christi Memorial Coliseum. -

Mexico's Nashville, Its Country- Mexican Country Kitchen

till * 2 2 (i ii i I f a 1 I 25 I m MCXICO'S NASHVILLE B Y S E R G I O M A R T T N E Z Ano uY to Indepundencia (1910, Alfred Giles). MY MOTHER Ttus me that my grandfather In the 'NOs, radio programmers began Ezequiel liked parties and sharing good offering Mexicans music in their own times with his friends. We're talking language. Suddenly, norteno commanded about the If >0s, the young adulthood ot the eyes and ears ol all Mexico — and my grandparents, the childhood of my also of fans in the United States. Dances mother, a Monterrey of possibly 100,000 ireally concerts) drew up to 150,000 inhabitants. Almost every weekend, my people. To accommodate the crowds, grandparents converted their house into a norteno events were held in parks and kind of party hall. They butchered a even soccer stadiums. sheep or kid goat, or maybe a call if the Bronco's lead singer, Lupe Esparza, party was very big, and they arranged a opened his own recording studio in big pit barbecue. Or it they had a pig, Monterrey, and l.os Jemararios and other there was a little festival of chicharrones, I groups soon followed sun. Monterrey carnitas, and other delicacies of the became Mexico's Nashville, its country- Mexican country kitchen. music capital. Music wasn't lacking. It was norteno, Norteno's popularity favored an inter- the regional music of northeastern Mexico change between Mexico and the United — a rural, working-class music, the coun- States — not just a commercial inter- try music of Mexico. -

Section I - Overview

EDUCATOR GUIDE Story Theme: Street Art Subject: Los Cazadores del Sur Discipline: Music SECTION I - OVERVIEW ......................................................................................................................2 EPISODE THEME SUBJECT CURRICULUM CONNECTIONS OBJECTIVE STORY SYNOPSIS INSTRUCTIONAL OBJECTIVES INSTRUCTIONAL STRATEGIES EQUIPMENT NEEDED MATERIALS NEEDED INTELLIGENCES ADDRESSED SECTION II – CONTENT/CONTEXT ..................................................................................................3 CONTENT OVERVIEW THE BIG PICTURE SECTION III – RESOURCES .................................................................................................................6 TEXTS DISCOGRAPHY WEB SITES VIDEOS BAY AREA FIELD TRIPS SECTION III – VOCABULARY.............................................................................................................9 SECTION IV – ENGAGING WITH SPARK ...................................................................................... 11 Los Cazadores del Sur preparing for a work day. Still image from SPARK story, February 2005. SECTION I - OVERVIEW EPISODE THEME INSTRUCTIONAL STRATEGIES Street Art Individual and group research Individual and group exercises SUBJECT Written research materials Los Cazadores del Sur Group oral discussion, review and analysis GRADE RANGES K-12, Post-Secondary EQUIPMENT NEEDED TV & VCR with SPARK story “Street Art,” about CURRICULUM CONNECTIONS duo Los Cazadores del Sur Music, Social Studies Computer with Internet access, navigation software, -

Being Edward James Olmos: Culture Clash and the Portrayal of Chicano Masculinity

Studies in 20th & 21st Century Literature Volume 32 Issue 2 Theater and Performance in Nuestra Article 12 América 6-1-2008 Being Edward James Olmos: Culture Clash and the Portrayal of Chicano Masculinity Nohemy Solózano-Thompson Whitman College Follow this and additional works at: https://newprairiepress.org/sttcl Part of the Film and Media Studies Commons This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 4.0 License. Recommended Citation Solózano-Thompson, Nohemy (2008) "Being Edward James Olmos: Culture Clash and the Portrayal of Chicano Masculinity," Studies in 20th & 21st Century Literature: Vol. 32: Iss. 2, Article 12. https://doi.org/ 10.4148/2334-4415.1686 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by New Prairie Press. It has been accepted for inclusion in Studies in 20th & 21st Century Literature by an authorized administrator of New Prairie Press. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Being Edward James Olmos: Culture Clash and the Portrayal of Chicano Masculinity Abstract This paper analyzes how Culture Clash problematizes Chicano masculinity through the manipulation of two iconic Chicano characters originally popularized by two films starring dwarE d James Olmos - the pachuco from Luis Valdez’s Zoot Suit (1981) and the portrayal of real-life math teacher Jaime Escalante in Stand and Deliver (1988). In “Stand and Deliver Pizza” (from A Bowl of Beings, 1992), Culture Clash tries to introduce new Chicano characters that can be read as masculine, and who at the same time, display alternative behaviors and characteristics, including homosexual desire. The three characters in “Stand and Deliver Pizza” represent stock icons of Chicano masculinity. -

The Songs of Mexican Nationalist, Antonio Gomezanda

University of Northern Colorado Scholarship & Creative Works @ Digital UNC Dissertations Student Research 5-5-2016 The onS gs of Mexican Nationalist, Antonio Gomezanda Juanita Ulloa Follow this and additional works at: http://digscholarship.unco.edu/dissertations Recommended Citation Ulloa, Juanita, "The onS gs of Mexican Nationalist, Antonio Gomezanda" (2016). Dissertations. Paper 339. This Text is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Research at Scholarship & Creative Works @ Digital UNC. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholarship & Creative Works @ Digital UNC. For more information, please contact [email protected]. © 2016 JUANITA ULLOA ALL RIGHTS RESERVED UNIVERSITY OF NORTHERN COLORADO Greeley, Colorado The Graduate School THE SONGS OF MEXICAN NATIONALIST, ANTONIO GOMEZANDA A Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Arts Juanita M. Ulloa College of Visual and Performing Arts School of Music Department of Voice May, 2016 This Dissertation by: Juanita M. Ulloa Entitled: The Songs of Mexican Nationalist, Antonio Gomezanda has been approved as meeting the requirement for the Degree of Doctor of Arts in College of Visual and Performing Arts, School of Music, Department of Voice Accepted by the Doctoral Committee ____________________________________________________ Dr. Melissa Malde, D.M.A., Co-Research Advisor ____________________________________________________ Dr. Paul Elwood, Ph.D., Co-Research Advisor ____________________________________________________ Dr. Carissa Reddick, Ph.D., Committee Member ____________________________________________________ Professor Brian Luedloff, M.F.A., Committee Member ____________________________________________________ Dr. Robert Weis, Ph.D., Faculty Representative Date of Dissertation Defense . Accepted by the Graduate School ____________________________________________________________ Linda L. Black, Ed.D. -

Chicano Resistance in the Southwest

Chicano Resistance In The Southwest Alfred Porras, Jr. INTRODUCTION There are two dimensions of racism, economic and cultural, as indicated by Christine E. Sleeter (1). The first dimension involves “violent conquest, accompanied by the construction of a belief system that the conquering group is culturally and intellectually superior to the group it has conquered.” The second dimension involves ongoing attempts by the colonizing society to consolidate and stabilize control over the land and people, and to incorporate the people into the labor force in subordinate positions. At the cultural level, the colonizing group proclaims the superiority of its social system. During times of rebellion or instability, the dominant society reinforces its dominance through violence, and through assault on the culture, language, religion, or moral fiber of the subordinate group. (2) Based on this definition of racism I begin my study of Chicano resistance in the “American” Southwest, since Sleeter’s first dimension is clearly present in the United States military takeover “with forcible measures to overturn Mexican land-ownership claims and to undermine Mexican culture, the Spanish language, and the Catholic religion."(3) This curriculum unit concerning conflict and resolution has the purpose to dispel the myth of the sleeping giant or the idea that the Mexican American people are unaware of their political potential. This curriculum unit will address three basic questions. What is conflict and resistance? What are the roots of conflict? What are the different modes of resistance? According to Robert J. Rosenbaum, the history of the Mexican-American War of the mid-1800's indicates that it was a quick war and no real resistance occurred during the take over of Mexican land and during the imposition of dominance by the U.S. -

The Formation of Subjectivity in Mexican American Life Narratives

University of New Mexico UNM Digital Repository American Studies ETDs Electronic Theses and Dissertations 2-9-2011 Ghostly I(s)/Eyes: The orF mation of Subjectivity in Mexican American Life Narratives Patricia Marie Perea Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/amst_etds Recommended Citation Perea, Patricia Marie. "Ghostly I(s)/Eyes: The orF mation of Subjectivity in Mexican American Life Narratives." (2011). https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/amst_etds/34 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Electronic Theses and Dissertations at UNM Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in American Studies ETDs by an authorized administrator of UNM Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. i ii © 2010, Patricia Marie Perea iii DEDICATION por mi familia The smell of cedar can break the feed yard. Some days I smell nothing until she opens her chest. Her polished nails click against tarnished metal Cleek! Then the creek of the hinge and the memories open, naked and total. There. A satin ribbon curled around a ringlet of baby fine hair. And there. A red and white tassel, its threads thick and tangled. Look here. She picks up a newspaper clipping, irons out the wrinkles between her hands. I kept this. We remember this. It is ours. iv ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Until quite recently, I did not know how many years ago this dissertation began. It did not begin with my first day in the Ph.D. program at the University of New Mexico in 2000. Nor did it begin with my first day as a graduate student at the University of Texas at Austin in 1997. -

CORRIDO NORTEÑO Y METAL PUNK. ¿Patrimonio Musical Urbano? Su Permanencia En Tijuana Y Sus Transformaciones Durante La Guerra Contra Las Drogas: 2006-2016

CORRIDO NORTEÑO Y METAL PUNK. ¿Patrimonio musical urbano? Su permanencia en Tijuana y sus transformaciones durante la guerra contra las drogas: 2006-2016. Tesis presentada por Pedro Gilberto Pacheco López. Para obtener el grado de MAESTRO EN ESTUDIOS CULTURALES Tijuana, B. C., México 2016 CONSTANCIA DE APROBACIÓN Director de Tesis: Dr. Miguel Olmos Aguilera. Aprobada por el Jurado Examinador: 1. 2. 3. Obviamente a Gilberto y a Roselia: Mi agradecimiento eterno y mayor cariño. A Tania: Porque tú sacrificio lo llevo en mi corazón. Agradecimientos: Al apoyo económico recibido por CONACYT y a El Colef por la preparación recibida. A Adán y Janet por su amistad y por al apoyo desde el inicio y hasta este último momento que cortaron la luz de mi casa. Los vamos a extrañar. A los músicos que me regalaron su tiempo, que me abrieron sus hogares, y confiaron sus recuerdos: Fernando, Rosy, Ángel, Ramón, Beto, Gerardo, Alejandro, Jorge, Alejandro, Taco y Eduardo. Eta tesis no existiría sin ustedes, los recordaré con gran afecto. Resumen. La presente tesis de investigación se inserta dentro de los debates contemporáneos sobre cultura urbana en la frontera norte de México y se resume en tres grandes premisas: la primera es que el corrido y el metal forman parte de dos estructuras musicales de larga duración y cambio lento cuya permanencia es una forma de patrimonio cultural. Para desarrollar esta premisa se elabora una reconstrucción historiográfica desde la irrupción de los géneros musicales en el siglo XIX, pasando a la apropiación por compositores tijuanenses a mediados del siglo XX, hasta llegar al testimonio de primera mano de los músicos contemporáneos. -

Spanish Videos Use the Find Function to Search This List

Spanish Videos Use the Find function to search this list Velázquez: The Nobleman of Painting 60 minutes, English. A compelling study of the Spanish artist and his relationship with King Philip IV, a patron of the arts who served as Velazquez’ sponsor. LLC Library – Call Number: SP 070 CALL NO. SP 070 Aguirre, The Wrath of God Director: Werner Herzog with Klaus Kinski. 1972, 94 minutes, German with English subtitles. A band of Spanish conquistadors travels into the Amazon jungle searching for the legendary city of El Dorado, but their leader’s obsessions soon turn to madness. LLC Library CALL NO. Look in German All About My Mother Director: Pedro Almodovar with Cecilia Roth, Penélope Cruz, Marisa Perdes, Candela Peña, Antonia San Juan. 1999, 102 minutes, Spanish with English subtitles. Pedro Almodovar delivers his finest film yet, a poignant masterpiece of unconditional love, survival and redemption. Manuela is the perfect mother. A hard-working nurse, she’s built a comfortable life for herself and her teenage son, an aspiring writer. But when tragedy strikes and her beloved only child is killed in a car accident, her world crumbles. The heartbroken woman learns her son’s final wish was to know of his father – the man she abandoned when she was pregnant 18 years earlier. Returning to Barcelona in search on him, Manuela overcomes her grief and becomes caregiver to a colorful extended family; a pregnant nun, a transvestite prostitute and two troubled actresses. With riveting performances, unforgettable characters and creative plot twists, this touching screwball melodrama is ‘an absolute stunner. -

Movimiento Alterado”*

ANAGRAMAS - UNIVERSIDAD DE MEDELLIN Mecanismos discursivos en los corridos mexicanos de presentación del “Movimiento Alterado”* Tanius Karam Cárdenas** Recibido: 2 de mayo de 2013 – Aprobado: 7 de junio de 2013 Resumen En este texto hacemos un primer acercamiento a las formas de representación lingüística de sus letras y audiovisual del llamado “movimiento alterado”, (o corrido alterado) que presenta una nueva modalidad de narco - corrido mexicano. Para ello repasamos el concepto de narco - cultura en México; hacemos un resumen de la presencia del corrido en la cultura popular y de su doble mutación primero en narco - corrido y luego el auto - denominado “corrido alterado”. En la segunda parte de nuestro trabajo, describimos y analizamos dos de los principales videoclips de presentación de este auto - denominado “movimiento alterado” de corrido. Finalmente analizamos el vídeo interpretado por el “Komander” (“Mafia nueva”) donde se hace una caracterización del “nuevo mafioso”. A lo largo del análisis nos apoyamos eN distintas aspectos semióticos y pragmáticos que aplicamos a la letra, la música y la traducción narrativa en el videoclip. Palabras clave: violencia, corrido, narco - cultura, discurso, semiótica, videoclip. * El presente artículo es parte del proyecto “Nuevas expresiones de la violencia en la ecología cultural del México contemporáneo”. ** Investigador Universidad Anáhuac, México Norte. Doctor en Ciencias de la Información por la Universidad Complutense de Madrid. Es también miembro del Sistema Nacional de Investigadores. Es profesor - investigador de la Facultad de Comunicación de la Universidad Anáhuac, México Norte. Ha sido también profesor de la Ciudad de México (UACM). Ha sido profesor invitado de las universidades: Heinrich Heine (Dusseldorf, Alemania), de Toulouse (Francia), UnCuyo (Mendoza, Argentina), entre otras.