Season 2016-2017

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Season 2018-2019 the Philadelphia Orchestra

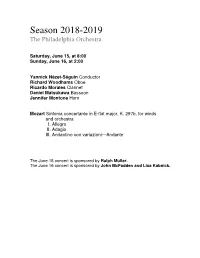

Season 2018-2019 The Philadelphia Orchestra Saturday, June 15, at 8:00 Sunday, June 16, at 2:00 Yannick Nézet-Séguin Conductor Richard Woodhams Oboe Ricardo Morales Clarinet Daniel Matsukawa Bassoon Jennifer Montone Horn Mozart Sinfonia concertante in E-flat major, K. 297b, for winds and orchestra I. Allegro II. Adagio III. Andantino con variazioni—Andante The June 15 concert is sponsored by Ralph Muller. The June 16 concert is sponsored by John McFadden and Lisa Kabnick. 24 The Philadelphia Orchestra Jessica Griffin The Philadelphia Orchestra Philadelphia is home and orchestra, and maximizes is one of the preeminent the Orchestra continues impact through Research. orchestras in the world, to discover new and The Orchestra’s award- renowned for its distinctive inventive ways to nurture winning Collaborative sound, desired for its its relationship with its Learning programs engage keen ability to capture the loyal patrons at its home over 50,000 students, hearts and imaginations of in the Kimmel Center, families, and community audiences, and admired for and also with those who members through programs a legacy of imagination and enjoy the Orchestra’s area such as PlayINs, side-by- innovation on and off the performances at the Mann sides, PopUP concerts, concert stage. The Orchestra Center, Penn’s Landing, free Neighborhood is inspiring the future and and other cultural, civic, Concerts, School Concerts, transforming its rich tradition and learning venues. The and residency work in of achievement, sustaining Orchestra maintains a Philadelphia and abroad. the highest level of artistic strong commitment to Through concerts, tours, quality, but also challenging— collaborations with cultural residencies, presentations, and exceeding—that level, and community organizations and recordings, the on a regional and national by creating powerful musical Orchestra is a global cultural level, all of which create experiences for audiences at ambassador for Philadelphia greater access and home and around the world. -

Rachmaninoff, Paganini, & the Piano; a Conversation

Rachmaninoff, Paganini, & the Piano; a Conversation Tracks and clips 1. Rachmaninoff in Paris 16:08 a. Niccolò Paganini, 24 Caprices for Solo Violin, Op. 1, Michael Rabin, EMI 724356799820, recorded 9/5/1958. b. Sergey Rachmaninoff (SR), Rapsodie sur un theme de Paganini, Op. 43, SR, Leopold Stokowski, Philadelphia Orchestra (PO), BMG Classics 09026-61658, recorded 12/24/1934 (PR). c. Fryderyk Franciszek Chopin (FC), Twelve Études, Op. 25, Alfred Cortot, Deutsche Grammophon Gesellschaft (DGG) 456751, recorded 7/1935. d. SR, Piano Concerto No. 3 in d, Op. 30, SR, Eugene Ormandy (EO), PO, Naxos 8.110601, recorded 12/4/1939.* e. Carl Maria von Weber, Rondo Brillante in E♭, J. 252, Julian Jabobson, Meridian CDE 84251, released 1993.† f. FC, Twelve Études, Op. 25, Ruth Slenczynska (RS), Musical Heritage Society MHS 3798, released 1978. g. SR, Preludes, Op. 32, RS, Ivory Classics 64405-70902, recorded 4/8/1984. h. Georges Enesco, Cello & Piano Sonata, Op. 26 No. 2, Alexandre Dmitriev, Alexandre Paley, Saphir Productions LVC1170, released 10/29/2012.† i. Claude Deubssy, Children’s Corner Suite, L. 113, Walter Gieseking, Dante 167, recorded 1937. j. Ibid., but SR, Victor B-24193, recorded 4/2/1921, TvJ35-zZa-I. ‡ k. SR, Piano Concerto No. 3 in d, Op. 30, Walter Gieseking, John Barbirolli, Philharmonic-Symphony Orchestra, Music & Arts MACD 1095, recorded 2/1939.† l. SR, Preludes, Op. 23, RS, Ivory Classics 64405-70902, recorded 4/8/1984. 2. Rachmaninoff & Paganini 6:08 a. Niccolò Paganini, op. cit. b. PR. c. Arcangelo Corelli, Violin Sonata in d, Op. 5 No. 12, Pavlo Beznosiuk, Linn CKD 412, recorded 1/11/2012.♢ d. -

Rachmaninoff's Rhapsody on a Theme By

RACHMANINOFF’S RHAPSODY ON A THEME BY PAGANINI, OP. 43: ANALYSIS AND DISCOURSE Heejung Kang, B.A., M.M. Dissertation Prepared for the Degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS UNIVERSITY OF NORTH TEXAS May 2004 APPROVED: Pamela Mia Paul, Major Professor and Program Coordinator Stephen Slottow, Minor Professor Josef Banowetz, Committee Member Steven Harlos, Interim Chair of Piano Jessie Eschbach, Chair of Keyboard Studies James Scott, Dean of the College of Music Sandra L. Terrill, Interim Dean of the Robert B. Toulouse School of Graduate Studies Kang, Heejung, Rachmaninoff’s Rhapsody on a Theme by Paganini, Op.43: Analysis and Discourse. Doctor of Musical Arts (Performance), May 2004, 169 pp., 40 examples, 5 figures, bibliography, 39 titles. This dissertation on Rachmaninoff’s Rhapsody on a Theme by Paganini, Op.43 is divided into four parts: 1) historical background and the state of the sources, 2) analysis, 3) semantic issues related to analysis (discourse), and 4) performance and analysis. The analytical study, which constitutes the main body of this research, demonstrates how Rachmaninoff organically produces the variations in relation to the theme, designs the large-scale tonal and formal organization, and unifies the theme and variations as a whole. The selected analytical approach is linear in orientation - that is, Schenkerian. In the course of the analysis, close attention is paid to motivic detail; the analytical chapter carefully examines how the tonal structure and motivic elements in the theme are transformed, repeated, concealed, and expanded throughout the variations. As documented by a study of the manuscripts, the analysis also facilitates insight into the genesis and structure of the Rhapsody. -

Ravel & Rachmaninoff

NOTES ON THE PROGRAM BY LAURIE SHULMAN, ©2017 2018 Winter Festival America, Inspiring: Ravel & Rachmaninoff ONE-MINUTE NOTES Martinů: Thunderbolt P-47. A World War II American fighter jet was the inspiration for this orchestral scherzo. Martinů pays homage to technology, the machine age and the brave pilots who risked death, flying these bombers to win the war. Ravel: Piano Concerto in G Major. Ravel was enthralled by American jazz, whose influence is apparent in this jazzy concerto. The pristine slow movement concerto evokes Mozart’s spirit in its clarity and elegance. Ravel’s wit sparkles in the finale, proving that he often had a twinkle in his eye. Rachmaninoff: Symphonic Dances. Rachmaninoff’s final orchestral work, a commission from the Philadelphia Orchestra, brings together Russian dance and Eastern European mystery. Listen for the “Dies irae” at the thrilling close. MARTINŮ: Thunderbolt P-47, Scherzo for Orchestra, H. 309 BOHUSLAV MARTINŮ Born: December 8, 1890, in Polička, Czechoslovakia Died: August 28, 1959, in Liestal, nr. Basel, Switzerland Composed: 1945 World Premiere: December 19, 1945, in Washington, DC. Hans Kindler conducted the National Symphony. NJSO Premiere: These are the NJSO premiere performances. Duration: 11 minutes Between 1941 and 1945, Republic Aviation built 15,636 P-47 Thunderbolt fighter planes. Introduced in November 1942, the aircraft was a bomber equipped with machine guns. British, French and American air forces used them for the last three years of the war. Early in 1945, the Dutch émigré conductor Hans Kindler commissioned Bohuslav Martinů—himself an émigré from Czechoslovakia who had resided in the United States since March 1941—to write a piece for the National Symphony Orchestra. -

Explore Unknown Music with the Toccata Discovery Club

Explore Unknown Music with the Toccata Discovery Club Since you’re reading this booklet, you’re obviously someone who likes to explore music more widely than the mainstream offerings of most other labels allow. Toccata Classics was set up explicitly to release recordings of music – from the Renaissance to the present day – that the microphones have been ignoring. How often have you heard a piece of music you didn’t know and wondered why it hadn’t been recorded before? Well, Toccata Classics aims to bring this kind of neglected treasure to the public waiting for the chance to hear it – from the major musical centres and from less-well-known cultures in northern and eastern Europe, from all the Americas, and from further afield: basically, if it’s good music and it hasn’t yet been recorded, Toccata Classics is exploring it. To link label and listener directly we run the Toccata Discovery Club, which brings its members substantial discounts on all Toccata Classics recordings, whether CDs or downloads, and also on the range of pioneering books on music published by its sister company, Toccata Press. A modest annual membership fee brings you, free on joining, two CDs, a Toccata Press book or a number of album downloads (so you are saving from the start) and opens up the entire Toccata Classics catalogue to you, both new recordings and existing releases as CDs or downloads, as you prefer. Frequent special offers bring further discounts. If you are interested in joining, please visit the Toccata Classics website at www.toccataclassics.com and click on the ‘Discovery Club’ tab for more details. -

The AMICA BULLETIN AUTOMATIC MUSICAL INSTRUMENT COLLECTORS’ ASSOCIATION JANUARY/FEBRUARY 2002 VOLUME 39, NUMBER 1 Mooluriil's MAGAZINE

The AMICA BULLETIN AUTOMATIC MUSICAL INSTRUMENT COLLECTORS’ ASSOCIATION JANUARY/FEBRUARY 2002 VOLUME 39, NUMBER 1 MoOLURIil'S MAGAZINE The Self-Playing Piano is It People who have watched these things closely have noticed that popular favor is toward the self-playing piano. A complete piano which will ornament your drawing-room, which can be played in the ordinary way by human fingers, or which. -'\ can be played by a piano player concealed inside the case, is the most popular musical instrument in the world to-day. The Harmonist Self-Playing Piano is the instrument which best meets these condi tions. The piano itself is perfect in tone and workmanship. The piano player at tachment is inside, is operated by perforated music, adds nothing to the size of the piano. takes up no room whatever, is always ready, is never in the way. We want everyone who is thinking of buying a piano to consider the great advan tage of getting a Harmonist, which combines the piano and the piano player both. It costs but little more than a good piano. but it is ten times as useful and a hundred times as entertaining. Write for particulars. ROTH ~ENGELHARDT Proprietors Peerless Piano Player Co. Windsor Aroade. Fifth Ave.. New York Please mention McClure·s when you write to ad"crtiscrt. 77 THE AMICA BULLETIN AUTOMATIC MUSICAL INSTRUMENT COLLECTORS' ASSOCIATION Published by the Automatic Musical Instrument Collectors’ Association, a non-profit, tax exempt group devoted to the restoration, distribution and enjoyment of musical instruments using perforated paper music rolls and perforated music books. -

Elizabeth Joy Roe, Piano

The John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts STEPHEN A. SCHWARZMAN , Chairman MICHAEL M. KAISER , President TERRACE THEATER Saturday Evening, October 31, 2009, at 7:30 presents Elizabeth Joy Roe, Piano BACH/SILOTI Prelude in B minor CORIGLIANO Etude Fantasy (1976) For the Left Hand Alone Legato Fifths to Thirds Ornaments Melody CHOPIN Nocturne in C-sharp minor, Op. 27, No. 1 WAGNER/LISZT Isoldens Liebestod RAVEL La Valse Intermission MUSSORGSKY Pictures at an Exhibition Promenade The Gnome Promenade The Old Castle Promenade Tuileries The Ox-Cart Promenade Ballet of the Unhatched Chicks Samuel Goldenberg and Schmuyle Promenade The Market at Limoges (The Great News) The Catacombs With the Dead in a Dead Language Baba-Yaga’s Hut The Great Gate of Kiev Elizabeth Joy Roe is a Steinway Artist Patrons are requested to turn off pagers, cellular phones, and signal watches during performances. The taking of photographs and the use of recording equipment are not allowed in this auditorium. Notes on the Program By Elizabeth Joy Roe Prelude in B minor Liszt and Debussy. Yet Corigliano’s etudes JOHANN SEBASTIAN BACH ( 1685 –1750) are distinctive in their effective synthesis of trans. ALEXANDER SILOTI (1863 –1945) stark dissonance and an expressive landscape grounded in Romanticism. Alexander Siloti, the legendary Russian pianist, The interval of a second—and its inversion composer, conductor, teacher, and impresario, and expansion to sevenths and ninths—is the was the bearer of an impressive musical lineage. connective thread between the etudes; its per - He studied with Franz Liszt and was the cousin mutations supply the foundation for the work’s and mentor of Sergei Rachmaninoff. -

Rachmaninoff's Piano Works and Diasporic Identity 1890-1945: Compositional Revision and Discourse

Western University Scholarship@Western Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository 8-7-2018 12:30 PM Rachmaninoff's Piano Works and Diasporic Identity 1890-1945: Compositional Revision and Discourse Renee MacKenzie The University of Western Ontario Supervisor Nolan, Catherine The University of Western Ontario Sylvestre, Stéphan The University of Western Ontario Kinton, Leslie The University of Western Ontario Graduate Program in Music A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree in Doctor of Musical Arts © Renee MacKenzie 2018 Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd Part of the Music Performance Commons Recommended Citation MacKenzie, Renee, "Rachmaninoff's Piano Works and Diasporic Identity 1890-1945: Compositional Revision and Discourse" (2018). Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository. 5572. https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd/5572 This Dissertation/Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship@Western. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository by an authorized administrator of Scholarship@Western. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Abstract This monograph examines the post-exile, multi-version works of Sergei Rachmaninoff with a view to unravelling the sophisticated web of meanings and values attached to them. Compositional revision is an important and complex aspect of creating musical meaning. Considering revision offers an important perspective on the construction and circulation of meanings and discourses attending Rachmaninoff’s music. While Rachmaninoff achieved international recognition during the 1890s as a distinctively Russian musician, I argue that Rachmaninoff’s return to certain compositions through revision played a crucial role in the creation of a narrative and set of tropes representing “Russian diaspora” following the 1917 Bolshevik Revolution. -

Toccata Classics Cds Are Also Available in the Shops and Can Be Ordered from Our Distributors Around the World, a List of Whom Can Be Found At

Recorded in the Great Hall of the Moscow Conservatoire on 25–27 June 2013 Recording engineers: Maria Soboleva (Piano Concerto) and Pavel Lavrenenkov (Cello Concerto) Booklet essays by Anastasia Belina and Malcolm MacDonald Design and layout: Paul Brooks, [email protected] Executive producer: Martin Anderson TOCC 0219 © 2014, Toccata Classics, London P 2014, Toccata Classics, London Come and explore unknown music with us by joining the Toccata Discovery Club. Membership brings you two free CDs, big discounts on all Toccata Classics recordings and Toccata Press books, early ordering on all Toccata releases and a host of other benefits, for a modest annual fee of £20. You start saving as soon as you join. You can sign up online at the Toccata Classics website at www.toccataclassics.com. Toccata Classics CDs are also available in the shops and can be ordered from our distributors around the world, a list of whom can be found at www.toccataclassics.com. If we have no representation in your country, please contact: Toccata Classics, 16 Dalkeith Court, Vincent Street, London SW1P 4HH, UK Tel: +44/0 207 821 5020 E-mail: [email protected] A student of Ferdinand Leitner in Salzburg and Leonard Bernstein and Seiji Ozawa at Tanglewood, Hobart Earle studied conducting at the Academy of Music in Vienna; received a performer’s diploma in IGOR RAYKHELSON: clarinet from Trinity College of Music, London; and is a magna cum laude graduate of Princeton University, where he studied composition with Milton Babbitt, Edward Cone, Paul Lansky and Claudio Spies. In 2007 ORCHESTRAL MUSIC, VOLUME THREE he was awarded the title of Honorary Professor of the Academy of Music in Odessa. -

Rachmaninoff's Early Piano Works and the Traces of Chopin's Influence

Rachmaninoff’s Early Piano works and the Traces of Chopin’s Influence: The Morceaux de Fantaisie, Op.3 & The Moments Musicaux, Op.16 A document submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Cincinnati in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts in the Division of Keyboard Studies of the College-Conservatory of Music by Sanghie Lee P.D., Indiana University, 2011 B.M., M.M., Yonsei University, Korea, 2007 Committee Chair: Jonathan Kregor, Ph.D. Abstract This document examines two of Sergei Rachmaninoff’s early piano works, Morceaux de Fantaisie, Op.3 (1892) and Moments Musicaux, Opus 16 (1896), as they relate to the piano works of Frédéric Chopin. The five short pieces that comprise Morceaux de Fantaisie and the six Moments Musicaux are reminiscent of many of Chopin’s piano works; even as the sets broadly build on his character genres such as the nocturne, barcarolle, etude, prelude, waltz, and berceuse, they also frequently are modeled on or reference specific Chopin pieces. This document identifies how Rachmaninoff’s sets specifically and generally show the influence of Chopin’s style and works, while exploring how Rachmaninoff used Chopin’s models to create and present his unique compositional identity. Through this investigation, performers can better understand Chopin’s influence on Rachmaninoff’s piano works, and therefore improve their interpretations of his music. ii Copyright © 2018 by Sanghie Lee All rights reserved iii Acknowledgements I cannot express my heartfelt gratitude enough to my dear teacher James Tocco, who gave me devoted guidance and inspirational teaching for years. -

Boston Symphony Orchestra Concert Programs, Season 90, 1970-1971

v^ BOSTON SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA FOUNDED IN 1881 BY HENRY LEE HIGGINSON THURSDAY B 2 FRIDAY -SATURDAY 16 1970-1971 NINETIETH ANNIVERSARY SEASON IP» STRADIVARI created for all time a perfect marriage of precision and beauty for both the eye and the ear. He had the unique genius to combine a thorough knowledge of the acoustical values of wood with a fine artist's sense of the good and the beautiful. Unexcelled by anything before or after, his violins have such purity of tone, they are said to speak with the voice of a lovely soul within. In business, as in the arts, experience and ability are invaluable. We suggest you take advantage of our extensive insurance background by letting us review your needs either business or personal and counsel you to an intelligent program. We respectfully invite your inquiry. CHARLES H. WATKINS & CO., INC Richard P. Nyquist, President Charles G. Carleton, Vice President 147 Milk Street Boston, Massachusetts 02109 542-1250 OBRION, RUSSELL & CO. Insurance of Every Description BOSTON SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA WILLIAM STEINBERG Music Director MICHAEL TILSON THOMAS Associate Conductor NINETIETH ANNIVERSARY SEASON 1970-1971 THE TRUSTEES OF THE BOSTON SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA INC. TALCOTT M. BANKS President FRANCIS W. HATCH PHILIP K. ALLEN Vice-President HAROLD D. HODGKINSON ROBERT H. GARDINER Vice-President E. MORTON JENNINGS JR JOHN L. THORNDIKE Treasurer EDWARD M. KENNEDY ALLEN G. BARRY HENRY A. LAUGHLIN RICHARD P. CHAPMAN EDWARD G. MURRAY ABRAM T. COLLIER JOHN T. NOONAN MRS HARRIS FAHNESTOCK MRS JAMES H. PERKINS THEODORE P. FERRIS IRVING W. RABB SIDNEY STONEMAN TRUSTEES EMERITUS HENRY B. -

The Singing Guitar

August 2011 | No. 112 Your FREE Guide to the NYC Jazz Scene nycjazzrecord.com Mike Stern The Singing Guitar Billy Martin • JD Allen • SoLyd Records • Event Calendar Part of what has kept jazz vital over the past several decades despite its commercial decline is the constant influx of new talent and ideas. Jazz is one of the last renewable resources the country and the world has left. Each graduating class of New York@Night musicians, each child who attends an outdoor festival (what’s cuter than a toddler 4 gyrating to “Giant Steps”?), each parent who plays an album for their progeny is Interview: Billy Martin another bulwark against the prematurely-declared demise of jazz. And each generation molds the music to their own image, making it far more than just a 6 by Anders Griffen dusty museum piece. Artist Feature: JD Allen Our features this month are just three examples of dozens, if not hundreds, of individuals who have contributed a swatch to the ever-expanding quilt of jazz. by Martin Longley 7 Guitarist Mike Stern (On The Cover) has fused the innovations of his heroes Miles On The Cover: Mike Stern Davis and Jimi Hendrix. He plays at his home away from home 55Bar several by Laurel Gross times this month. Drummer Billy Martin (Interview) is best known as one-third of 9 Medeski Martin and Wood, themselves a fusion of many styles, but has also Encore: Lest We Forget: worked with many different artists and advanced the language of modern 10 percussion. He will be at the Whitney Museum four times this month as part of Dickie Landry Ray Bryant different groups, including MMW.