Al'riq: the Arab Tambourine

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

THE SHARED INFLUENCES and CHARACTERISTICS of JAZZ FUSION and PROGRESSIVE ROCK by JOSEPH BLUNK B.M.E., Illinois State University, 2014

COMMON GROUND: THE SHARED INFLUENCES AND CHARACTERISTICS OF JAZZ FUSION AND PROGRESSIVE ROCK by JOSEPH BLUNK B.M.E., Illinois State University, 2014 A thesis submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Colorado in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Master in Jazz Performance and Pedagogy Department of Music 2020 Abstract Blunk, Joseph Michael (M.M., Jazz Performance and Pedagogy) Common Ground: The Shared Influences and Characteristics of Jazz Fusion and Progressive Rock Thesis directed by Dr. John Gunther In the late 1960s through the 1970s, two new genres of music emerged: jazz fusion and progressive rock. Though typically thought of as two distinct styles, both share common influences and stylistic characteristics. This thesis examines the emergence of both genres, identifies stylistic traits and influences, and analyzes the artistic output of eight different groups: Return to Forever, Mahavishnu Orchestra, Miles Davis’s electric ensembles, Tony Williams Lifetime, Yes, King Crimson, Gentle Giant, and Soft Machine. Through qualitative listenings of each group’s musical output, comparisons between genres or groups focus on instances of one genre crossing over into the other. Though many examples of crossing over are identified, the examples used do not necessitate the creation of a new genre label, nor do they demonstrate the need for both genres to be combined into one. iii Contents Introduction………………………………………………………………………………… 1 Part One: The Emergence of Jazz………………………………………………………….. 3 Part Two: The Emergence of Progressive………………………………………………….. 10 Part Three: Musical Crossings Between Jazz Fusion and Progressive Rock…………….... 16 Part Four: Conclusion, Genre Boundaries and Commonalities……………………………. 40 Bibliography………………………………………………………………………………. -

Music of Ghana and Tanzania

MUSIC OF GHANA AND TANZANIA: A BRIEF COMPARISON AND DESCRIPTION OF VARIOUS AFRICAN MUSIC SCHOOLS Heather Bergseth A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTERDecember OF 2011MUSIC Committee: David Harnish, Advisor Kara Attrep © 2011 Heather Bergseth All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT David Harnish, Advisor This thesis is based on my engagement and observations of various music schools in Ghana, West Africa, and Tanzania, East Africa. I spent the last three summers learning traditional dance- drumming in Ghana, West Africa. I focus primarily on two schools that I have significant recent experience with: the Dagbe Arts Centre in Kopeyia and the Dagara Music and Arts Center in Medie. While at Dagbe, I studied the music and dance of the Anlo-Ewe ethnic group, a people who live primarily in the Volta region of South-eastern Ghana, but who also inhabit neighboring countries as far as Togo and Benin. I took classes and lessons with the staff as well as with the director of Dagbe, Emmanuel Agbeli, a teacher and performer of Ewe dance-drumming. His father, Godwin Agbeli, founded the Dagbe Arts Centre in order to teach others, including foreigners, the musical styles, dances, and diverse artistic cultures of the Ewe people. The Dagara Music and Arts Center was founded by Bernard Woma, a master drummer and gyil (xylophone) player. The DMC or Dagara Music Center is situated in the town of Medie just outside of Accra. Mr. Woma hosts primarily international students at his compound, focusing on various musical styles, including his own culture, the Dagara, in addition music and dance of the Dagbamba, Ewe, and Ga ethnic groups. -

WORKSHOP: Around the World in 30 Instruments Educator’S Guide [email protected]

WORKSHOP: Around The World In 30 Instruments Educator’s Guide www.4shillingsshort.com [email protected] AROUND THE WORLD IN 30 INSTRUMENTS A MULTI-CULTURAL EDUCATIONAL CONCERT for ALL AGES Four Shillings Short are the husband-wife duo of Aodh Og O’Tuama, from Cork, Ireland and Christy Martin, from San Diego, California. We have been touring in the United States and Ireland since 1997. We are multi-instrumentalists and vocalists who play a variety of musical styles on over 30 instruments from around the World. Around the World in 30 Instruments is a multi-cultural educational concert presenting Traditional music from Ireland, Scotland, England, Medieval & Renaissance Europe, the Americas and India on a variety of musical instruments including hammered & mountain dulcimer, mandolin, mandola, bouzouki, Medieval and Renaissance woodwinds, recorders, tinwhistles, banjo, North Indian Sitar, Medieval Psaltery, the Andean Charango, Irish Bodhran, African Doumbek, Spoons and vocals. Our program lasts 1 to 2 hours and is tailored to fit the audience and specific music educational curriculum where appropriate. We have performed for libraries, schools & museums all around the country and have presented in individual classrooms, full school assemblies, auditoriums and community rooms as well as smaller more intimate settings. During the program we introduce each instrument, talk about its history, introduce musical concepts and follow with a demonstration in the form of a song or an instrumental piece. Our main objective is to create an opportunity to expand people’s understanding of music through direct expe- rience of traditional folk and world music. ABOUT THE MUSICIANS: Aodh Og O’Tuama grew up in a family of poets, musicians and writers. -

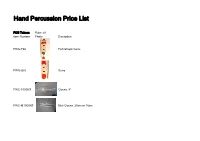

Hand Percussion Price List

Hand Percussion Price List FOB Taiwan Rate: 29 Item Number Photo Discription PWG-F86 Fish Shape Guiro PWG-S83 Guiro PWC-1000NT Claves, 8" PWC-M1000NT Mini Claves, 20cm or 18cm PWBG-T2 Two Tone Wood Block Scraper PWKH-RD Wooden Handle Castanet PWBG-1 Single Guiro Tone Block PSS-CC Coconut Shaker YD0-2H5A2 Drum Sticks, Hickory YD0-2M5A2 Drum Sticks, Maple YD0-2O5A Drum Sticks, Oak YD0-2H5AF(GR) Drum Sticks, Hickory, Fluorescent, 2-color YD0-2TB Timbale Sticks YD0-2RASBK Rods, anti-slip ORS-3111PU Recorder, Purple Transparent ORS-3111BL Recorder, Blue Transparent ORS-3111YE Recorder, Yellow Transparent ORS-3111OR Recorder, Orange Transparent ORS-3111GR Recorder, Green Transparent ORS-32BR Recorder, Brown ORS-32CR Recorder, Creamed Colored ORS-3221IB Recorder, Creamed Colored / Brown ORS-32PB Recorder, Pink / Light Blue PBS-H25 Sleigh Bell, 25 Bells PBS-H25B Sleigh Bell, 25 Bells (Brass Bell) PBS-M24 Mounted Sleigh Bell, 24 Bells PBS-M24B Mounted Sleigh Bell, 24 Bells (Brass Bell) PBS-H13 Sleigh Bell, 13 Bells PBS-H13B Sleigh Bell, 13 Bells (Brass Bell) PBS-H12 Sleigh Bell, 12 Bells PBS-M12 Mounted Sleigh Bell, 12 Bells PBS-M9 Sleigh Bell, 9 Bells PBS-M9B Sleigh Bell, 9 Bells (Brass Bell) PBS-M7 Sleigh Bell, 7 Bells PBS-M7B Sleigh Bell, 7 Bells (Brass Bell) PBS-M5 Sleigh Bell, 5 Bells PBS-M5B Sleigh Bell, 5 Bells (Brass Bell) PBS-M4 Sleigh Bell, 4 Bells PBS-M4B Sleigh Bell, 4 Bells (Brass Bell) PBS-H3 Sleigh Bell, 3 Bells PBS-H3B Sleigh Bell, 3 Bells (Brass Bell) PBS-M13 Mounted Sleigh Bell, 13 Bells PBS-M13B Mounted Sleigh Bell, 13 Bells -

The Music of the Bible, with an Account of the Development Of

\ \ ^ \ X \N x*S-s >> V \ X \ SS^^ \ 1 \ JOHN STAINER,M.A.,MUS,.DOC., Cornell University Library ML 166.S78 3 1924 022 269 058 CORNELL UNIVERSITY LIBRARY ^^S/C [7BRARY Cornell University Library The original of tliis book is in tine Cornell University Library. There are no known copyright restrictions in the United States on the use of the text. http://www.archive.org/details/cu31924022269058 THE MUSIC OF THE BIBLE WITH AN ACCOUNT OF THE Development of Modern Musical Instruments from Ancient Types BY JOHN STAINER, M.A.. MUS. DOC, MAGD. COLL., OXON. Cassell Fetter & Galpin LONDON, PARIS & NEW YORK. V Novell o, Ewer & Co.: LONDON. [all rights reserved.] PREFACE. No apology is needed, I hope, for issuing in this form the substance of the series of articles which I contributed to the Bible Educator. Some of the statements which I brought forward in that work have received further con- firmation by wider reading; but some others I have ventured to qualify or alter. Much new matter will be fotmd here which I trust may be of interest to the general reader, if not of use to the professional. I fully anticipate a criticism to the effect that such a subject as the development of musical instruments should rather have been allowed to stand alone than have been associated with Bible music. But I think all will admit that the study of the history of ancient nations, whether with reference to their arts, religion, conquests, or language, seems to gather and be concentrated round the Book of Books, and when once I began to treat of the com- parative history of musical instruments, I felt that a few more words, tracing their growth up to our own times, would make this little work more complete and useful than if I should deal only with the sparse records of Hebrew music. -

A Review of the Origin and Evolution of Uygur Musical Instruments

2019 International Conference on Humanities, Cultures, Arts and Design (ICHCAD 2019) A Review of the Origin and Evolution of Uygur Musical Instruments Xiaoling Wang, Xiaoling Wu Changji University Changji, Xinjiang, China Keywords: Uygur Musical Instruments, Origin, Evolution, Research Status Abstract: There Are Three Opinions about the Origin of Uygur Musical Instruments, and Four Opinions Should Be Exact. Due to Transliteration, the Same Musical Instrument Has Multiple Names, Which Makes It More Difficult to Study. So Far, the Origin of Some Musical Instruments is Difficult to Form a Conclusion, Which Needs to Be Further Explored by People with Lofty Ideals. 1. Introduction Uyghur Musical Instruments Have Various Origins and Clear Evolution Stages, But the Process is More Complex. I Think There Are Four Sources of Uygur Musical Instruments. One is the National Instrument, Two Are the Central Plains Instruments, Three Are Western Instruments, Four Are Indigenous Instruments. There Are Three Changes in the Development of Uygur Musical Instruments. Before the 10th Century, the Main Musical Instruments Were Reed Flute, Flute, Flute, Suona, Bronze Horn, Shell, Pottery Flute, Harp, Phoenix Head Harp, Kojixiang Pipa, Wuxian, Ruan Xian, Ruan Pipa, Cymbals, Bangling Bells, Pan, Hand Drum, Iron Drum, Waist Drum, Jiegu, Jilou Drum. At the Beginning of the 10th Century, on the Basis of the Original Instruments, Sattar, Tanbu, Rehwap, Aisi, Etc New Instruments Such as Thar, Zheng and Kalong. after the Middle of the 20th Century, There Were More Than 20 Kinds of Commonly Used Musical Instruments, Including Sattar, Trable, Jewap, Asitar, Kalong, Czech Republic, Utar, Nyi, Sunai, Kanai, Sapai, Balaman, Dapu, Narre, Sabai and Kashtahi (Dui Shi, or Chahchak), Which Can Be Divided into Four Categories: Choral, Membranous, Qiming and Ti Ming. -

Study Guide for the High School Percussionist

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers Graduate School 1965 Study guide for the high school percussionist Alan Anderson The University of Montana Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Anderson, Alan, "Study guide for the high school percussionist" (1965). Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers. 3698. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd/3698 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A STUDY GUIDE FOR THE HIGH SCHOOL PERCUSSIONIST by ALAN J. ANDERSON B. M. Montana State University, 1957 Presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of M aster of Music UNIVERSITY OF MONTANA 1965 Approved by: Chairman, Board of Exarqi rs D q^, Graduate School SEP 2 2 1965 D ate UMI Number: EP35326 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. UMT UMI EP35326 Published by ProQuest LLC (2012). Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. -

Quantum Leap Stormdrum 3 Manual

Quantum Leap Stormdrum 3 Virtual Instrument Users’ Manual QUANTUM LEAP STORMDRUM 3 VIRTUAL INSTRUMENT The information in this document is subject to change without notice and does not rep- resent a commitment on the part of East West Sounds, Inc. The software and sounds described in this document are subject to License Agreements and may not be copied to other media. No part of this publication may be copied, reproduced or otherwise transmitted or recorded, for any purpose, without prior written permission by East West Sounds, Inc. All product and company names are ™ or ® trademarks of their respective owners. Solid State Logic (SSL) Channel Strip, Transient Shaper, and Stereo Compressor licensed from Solid State Logic. SSL and Solid State Logic are registered trademarks of Red Lion 49 Ltd. © East West Sounds, Inc., 2013. All rights reserved. East West Sounds, Inc. 6000 Sunset Blvd. Hollywood, CA 90028 USA 1-323-957-6969 voice 1-323-957-6966 fax For questions about licensing of products: [email protected] For more general information about products: [email protected] http://support.soundsonline.com ii QUANTUM LEAP STORMDRUM 3 VIRTUAL INSTRUMENT 1. Welcome 2 About EastWest and Quantum Leap 3 Producer: Nick Phoenix 4 Percussionist: Mickey Hart 5 Credits 6 How to Use This and the Other Manuals 7 Online Documentation and Other Resources Click on this text to open the Master Navigation Document 1 QUANTUM LEAP STORMDRUM 3 VIRTUAL INSTRUMENT Welcome About EastWest and Quantum Leap Founder and producer Doug Rogers has over 35 years experience in the audio industry and is the recipient of many recording industry awards including “Recording Engineer of the Year.” In 2005, “The Art of Digital Music” named him one of “56 Visionary Artists & Insiders” in the book of the same name. -

The William Paterson University Department of Music Presents New

The William Paterson University Department of Music presents New Music Series Peter Jarvis, director Featuring the Velez / Jarvis Duo, Judith Bettina & James Goldsworthy, Daniel Lippel and the William Paterson University Percussion Ensemble Monday, October 17, 2016, 7:00 PM Shea Center for the Performing Arts Program Mundus Canis (1997) George Crumb Five Humoresques for Guitar and Percussion 1. “Tammy” 2. “Fritzi” 3. “Heidel” 4. “Emma‐Jean” 5. “Yoda” Phonemena (1975) Milton Babbitt For Voice and Electronics Judith Bettina, voice Phonemena (1969) Milton Babbitt For Voice and Piano Judith Bettina, voice James Goldsworthy, Piano Penance Creek (2016) * Glen Velez For Frame Drums and Drum Set Glen Velez – Frame Drums Peter Jarvis – Drum Set Themes and Improvisations Peter Jarvis For open Ensemble Glen Velez & Peter Jarvis Controlled Improvisation Number 4, Opus 48 (2016) * Peter Jarvis For Frame Drums and Drum Set Glen Velez – Frame Drums Peter Jarvis – Drum Set Aria (1958) John Cage For a Voice of any Range Judith Bettina May Rain (1941) Lou Harrison For Soprano, Piano and Tam‐tam Elsa Gidlow Judith Bettina, James Goldsworthy, Peter Jarvis Ostinato Mezzo Forte, Opus 51 (2016) * Peter Jarvis For Percussion Band Evan Chertok, David Endean, Greg Fredric, Jesse Gerbasi Daniel Lucci, Elise Macloon Sean Dello Monaco – Drum Set * = World Premiere Program Notes Mundus Canis: George Crumb George Crumb’s Mundus Canis came about in 1997 when he wanted to write a solo guitar piece for his friend David Starobin that would be a musical homage to the lineage of Crumb family dogs. He explains, “It occurred to me that the feline species has been disproportionately memorialized in music and I wanted to help redress the balance.” Crumb calls the work “a suite of five canis humoresques” with a character study of each dog implied through the music. -

What Is Belly Dance?

What Is Belly Dance? THE PYRAMID DANCE CO. INC. was originally founded in Memphis 1987. With over 30 years Experience in Middle Eastern Dance, we are known for producing professional Dancers and Instructors in belly dancing! The company’s purpose is to teach, promote, study, and perform belly dance. Phone: 901.628.1788 E-mail: [email protected] PAGE 2 CONTACT: 901.628.1788 WHAT IS BELLY DANCE? PAGE 11 What is the belly dance? Sadiia is committed to further- ing belly dance in its various The dance form we call "belly dancing" is derived from forms (folk, modern, fusion , traditional women's dances of the Middle East and interpretive) by increasing pub- North Africa. Women have always belly danced, at lic awareness, appreciation parties, at family gatherings, and during rites of pas- and education through per- sage. A woman's social dancing eventually evolved formances, classes and litera- into belly dancing as entertainment ("Dans Oryantal " in ture, and by continuing to Turkish and "Raqs Sharqi" in Arabic). Although the his- study all aspects of belly tory of belly dancing is clouded prior to the late 1800s, dance and producing meaning- many experts believe its roots go back to the temple ful work. She offers her stu- rites of India. Probably the greatest misconception dents a fun, positive and nur- about belly dance is that it is intended to entertain men. turing atmosphere to explore Because segregation of the sexes was common in the movement and the proper part of the world that produced belly dancing, men of- techniques of belly dance, giv- ten were not allowed to be present. -

NSR Presskit

w world m u s i c a n d p e r c u s s i o n “Anyone who enjoys the work of Codona should find Things That Happen Fast the kind of music to which they are, in fact, likely to wish to return to again and again.” - Jazz Journal International “The compositions are strong, and Robinson should be commended for the unique timbres he blended in each one. World View is a breath of fresh air.” - Percussive Notes “That he has mastered his instruments and has studied the masters well is evident in every tone.” - Drums and Percussion “The man is a musical conjurer!” - Voice in the Wind Performance Options 1) N. Scott Robinson - solo world percussion concert or assembly program - 1 hour. 2) Wind & Fire - N. Scott Robinson & Mark Holland - flute & world percussion show. 3) N. Scott Robinson & K.S. Resmi- Indian World Music - featuring world percussion andCarnatic vocal from South India. Workshops and school visits can be combined with any of the concert performance options listed above. For individual show descriptions, availability, fees, sound, and space requirements, please contact by e-mail. Also see my other social media sites: http://www.facebook.com/nscottrobinson & http://www.youtube.com/nscottrob. h t t p : / / w w w . n s c o t t r o b i n s o n . c o m Booking Contact: [email protected] Biography World percussionist N. Scott Robinson, Ph.D., is an eclectic and engaging musician Discography suitable for a wide range of audiences, from university appearances to concert halls. -

MP-Price-List-2020-EUR.Pdf

PRICE LIST 2020 EURO Model Description Price PICKUP PICKUP INSTRUMENTS NEW MPDS1 digital percussion stomp box 199,00 € NEW MPS1 analog percussion stomp box 89,00 € NEW MPSM stomp box mount 49,90 € FX10 fx pedal 169,00 € PBASSBOX pickup bassbox 129,00 € PSNAREBOX pickup snarebox 119,00 € NEW MIC-PERC percussion microphone 24,90 € KA9P-AB pickup kalimba, african brown 99,90 € PICKUP CAJONS NEW PAESLDOB artisan edition pickup cajon, solea line 299,00 € PWCP100MB pickup cajon, woodcraft professional, makah-burl frontplate 199,00 € PSC100B pickup cajon, snarecraft, baltic birch frontplate 149,00 € PSUBCAJ6B pickup vertical subwoofer cajon, baltic birch 249,00 € PTOPCAJ2WN pickup slaptop cajon, turbo, walnut playing surface 189,00 € PTOPCAJ4MH-M pickup slaptop cajon, mahogany playing surface 149,00 € NEW PBASSCAJ-KIT cocktail cajon kit 499,00 € NEW PBASSCAJ cocktail cajon 169,90 € NEW PBC1B pickup bongo cajon 79,90 € NEW PCST pickup cajon snare tap 74,90 € NEW PCTT pickup cajon tom tap 69,90 € NEW MMCS mini cajon speaker 59,90 € PA-CAJ cajon preamp 99,00 € NEW CMS cajon microphone stand 9,90 € CAJONS ARTISAN EDITION CAJONS AEMLBI martinete line, brazilian ironwood with ukola woodframe frontplate 1.199,00 € AEFLIH fandango line, indian heartwood frontplate 699,00 € AESELIH seguiriya line, indian heartwood frontplate 469,00 € AESELCB seguiriya line, canyon-burl frontplate 469,00 € AECLWN cantina line, walnut frontplate 499,00 € AEBLLB buleria line, lava-burl frontplate 299,00 € AEBLMY buleria line, mongoy frontplate 299,00 € AESLEYB soleà line,