Undertaking a Tree and Urban Forest Assessment in the City of Johannesburg

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Have You Heard from Johannesburg?

Discussion Have You Heard from GuiDe Johannesburg Have You Heard Campaign support from major funding provided By from JoHannesburg Have You Heard from Johannesburg The World Against Apartheid A new documentary series by two-time Academy Award® nominee Connie Field TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction 3 about the Have you Heard from johannesburg documentary series 3 about the Have you Heard global engagement project 4 using this discussion guide 4 filmmaker’s interview 6 episode synopses Discussion Questions 6 Connecting the dots: the Have you Heard from johannesburg series 8 episode 1: road to resistance 9 episode 2: Hell of a job 10 episode 3: the new generation 11 episode 4: fair play 12 episode 5: from selma to soweto 14 episode 6: the Bottom Line 16 episode 7: free at Last Extras 17 glossary of terms 19 other resources 19 What you Can do: related organizations and Causes today 20 Acknowledgments Have You Heard from Johannesburg discussion guide 3 photos (page 2, and left and far right of this page) courtesy of archive of the anti-apartheid movement, Bodleian Library, university of oxford. Center photo on this page courtesy of Clarity films. Introduction AbouT ThE Have You Heard From JoHannesburg Documentary SEries Have You Heard from Johannesburg, a Clarity films production, is a powerful seven- part documentary series by two-time academy award® nominee Connie field that shines light on the global citizens’ movement that took on south africa’s apartheid regime. it reveals how everyday people in south africa and their allies around the globe helped challenge — and end — one of the greatest injustices the world has ever known. -

7.5. Identified Sites of Significance Residential Buildings Within Rosettenville (Semi-Detached, Freestanding)

7.5. Identified sites of significance_Residential buildings within Rosettenville (Semi-detached, freestanding) Introduction Residential buildings are buildings that are generally used for residential purposes or have been zoned for residential usage. It must be noted the majority of residences are over 60 years, it was therefore imperative for detailed visual study to be done where the most significant buildings were mapped out. Their significance could be as a result of them being associated to prominent figures, association with special events, design patterns of a certain period in history, rarity or part of an important architectural school. Most of the sites identified in this category are of importance in their local contexts and are representative of the historical and cultural patterns that could be discerned from the built environment. All the identified sites were given a 3A category explained below. Grading 3A_Sites that have a highly significant association with a historic person, social grouping, historic events, public memories, historical activities, and historical landmarks (should by all means be conserved) 3B_ Buildings of marginally lesser significance (possibility of senstive alteration and addition to the interior) 3C_Buildings and or sites whose significance is in large part significance that contributes to the character of significance of the environs (possibility for alteration and addition to the exterior) Summary Table of identified sites in the residential category: Site/ Description Provisional Heritage Implications -

South Africa – Cape Restaurants

Recommended Restaurants – Johannesburg and Pretoria JOHANNESBURG AFRICAN CUISINE ITALIAN/MEDITERRANEAN Moyo - Melrose Arch 2 Medeo Restaurant at The Palazzo 13 Moyo - Zoo Lake 2 La Cucina Di Ciro 14 Pronto 14 ASIAN Café del Sol Botanico 15 Kong Roast 3 The Lotus Teppanyaki & Sushi Bar 3 STEAKHOUSE Wombles Steakhouse Restaurant 15 BISTRO Turn 'n' Tender Illovo 16 Eatery JHB 4 Coobs 4 CONTEMPORARY Cube Tasting Kitchen 5 PRETORIA Winehouse - Ten Bompas 5 CONTEMPORARY Level Four Restaurant 6 Blu Saffron 16 March Restaurant 6 De Kloof Restaurant 17 Roots at Forum Homini - Prosopa Waterkloof Muldersdrift 7 17 FINE DINING FINE DINING Luke Dale Roberts X (Saxon Hotel) 7 Kream 18 DW Eleven-13 8 Restaurant Mosaic at The Orient 18 Signature Restaurant 8 Pigalle - Michelangelo Towers 9 Pigalle - Melrose Arch 9 oneNINEone 10 AtholPlace Restaurant 10 The Residence 11 FRENCH Emoyeni 11 Le Souffle 12 INDIAN Ghazal 12 Vikrams 13 1 **To make early reservations, please contact your AAC consultant, the hotel concierge or the restaurant directly.** JOHANNESBURG AFRICAN CUISINE MOYO (Melrose Arch) Shop 5, The High St / Tel: +27 11 684 1477 http://www.moyo.co.za/moyo-melrose-arch/ From the food and décor to the music and live entertainment, moyo is strongly African in theme. The focus of the rich and varied menu is pan-African, incorporating tandoori cookery from northern Africa, Cape Malay influences and other dishes representing South Africa. In the heart of Johannesburg, the 350-seater, multi-level modern restaurant – clad in copper with pressed pebble walls - embodies Africa’s finest music and urban cuisine offerings. -

T H E Soweto Stroke Q Uestionnaire

R esearch A rticle T h e S o w e t o S t r o k e Q uestionnaire ABSTRACT A questionnaire was designed for a recent survey into the outcome LA HALE CJ EALES VU FRITZ of stroke patients in Soweto, named the Soweto Stroke Questionnaire (SSQ). It was based on the Barthel ADL Index (BI) but modified to suit the local context. This paper introduces the SSQ, and reports on its inter-rater reliability and its concurrent validity. Fifty-four subjects, in the age range 30 to 75 years, were interviewed and nineteen re-interviewed using the SSQ. Four different scores were calculated: a total score, a Barthel Index score, an Impairment score, and a Quality of Life score. The Pearson’s Correlation Coefficient was found to be high between the total score and the BI score. (r=0.948) which supports the concurrent validity of the developed questionnaire. In assessing the reliability of the SQQ, the Wilcoxin Test showed that there was no signifi cant difference between the initial and repeat interviews for the total score, the Barthel Index score, and the Impairment score (p<0,05). The Quality of Life Score came closer to a difference, but not statistically significantly so. These tests were collaborated by Bland and Altman graphs which showed that in 95% of the time, the questions were repeatable. Me Nemar’s Test of Symmetry showed that 34 out of 38 questions asked were found to have over 70% correlation. Four questions showed a lower correlation, the lowest being 63.16%. -

Middle Classing in Roodepoort Capitalism and Social Change in South Africa

Middle Classing in Roodepoort Capitalism and Social Change in South Africa Ivor Chipkin June 2012 / PARI Long Essays / Number 2 Contents Acknowledgements ..................................................................................... 3 Preface ........................................................................................................ 5 Introduction: A Common World ................................................................. 7 1. Communal Capitalism ....................................................................... 13 2. Roodepoort City ................................................................................ 28 3.1. The Apartheid City ......................................................................... 33 3.2. Townhouse Complexes ............................................................... 35 3. Middle Class Settlements ................................................................... 41 3.1. A Black Middle Class ..................................................................... 46 3.2. Class, Race, Family ........................................................................ 48 4. Behind the Walls ............................................................................... 52 4.1. Townhouse and Suburb .................................................................. 52 4.2. Milky Way.................................................................................. 55 5. Middle-Classing................................................................................. 63 5.1. Blackness -

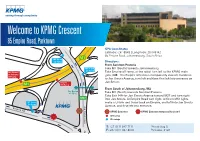

Welcome to KPMG Crescent

Jan Smuts Ave St Andrews M1 Off Ramp Winchester Rd Jan Smuts Off Ramp Welcome to KPMGM27 Crescent M1 North On Ramp De Villiers Graaff Motorway (M1) 85 Empire Road, Parktown St Andrews Rd Albany Rd GPS Coordinates Latitude: -26.18548 | Longitude: 28.045142 85 Empire Road, Johannesburg, South Africa M1 B M1 North On Ramp Directions: From Sandton/Pretoria M1 South Take M1 (South) towards Johannesburg On Ramp Jan Smuts / Take Empire off ramp, at the robot turn left to the KPMG main St Andrews gate. (NB – the Empire entrance is temporarily closed). Continue Off Ramp to Jan Smuts Avenue, turn left and then first left into entrance on Empire Jan Smuts. M1 Off Ramp From South of JohannesburgWellington Rd /M2 Sky Bridge 4th Floor Take M1 (North) towards Sandton/Pretoria Take Exit 14A for Jan Smuts Avenue toward M27 and turn right M27 into Jan Smuts. At Empire Road turn right, at first traffic lights M1 South make a U-turn and travel back on Empire, and left into Jan Smuts On Ramp M17 Jan Smuts Ave Avenue, and first left into entrance. Empire Rd KPMG Entrance KPMG Entrance temporarily closed Off ramp On ramp T: +27 (0)11 647 7111 Private Bag 9, Jan Jan Smuts Ave F: +27 (0)11 647 8000 Parkview, 2122 E m p ire Rd Welcome to KPMG Wanooka Place St Andrews Rd, Parktown NORTH GPS Coordinates Latitude: -26.182416 | Longitude: 28.03816 St Andrews Rd, Parktown, Johannesburg, South Africa M1 St Andrews Off Ramp Jan Smuts Ave Directions: Winchester Rd From Sandton/Pretoria Take M1 (South) towards Johannesburg Take St Andrews off ramp, at the robot drive straight to the KPMG Jan Smuts main gate. -

CITY of JOHANNESBURG – 24 May 2013 Structure of Presentation

2012/13 and 2013/14 BEPP/USDG REVIEW Portfolio Committee CITY OF JOHANNESBURG – 24 May 2013 Structure of Presentation 1. Overview of the City’s Development Agenda – City’s Urban Trends – Development Strategy and Approach – Capex process and implementation 2. Part One: 2012/13 Expenditure – Quarter One USDG expenditure 2012/13 – Quarter Two USDG expenditure 2012/13 – Quarter Three USDG expenditure 2012/13 – Quarter Four USDG expenditure 2012/13 – Recovery plan on 2012/13 USDG expenditure Part Two: 2013/14 Expenditure – Impact of the USDG for 2013/14 – Prioritization of 2013/14 projects 2 JOHANNESBURG DEMOGRAPHICS • Total Population – 4.4 million • 36% of Gauteng population • 8% of national population • Johanesburg is growing faster than the Gauteng Region • COJ population increase by 38% between 2001 and 2011. JOHANNESBURG POPULATION PYRAMID Deprivation Index Population Deprivation Index Based on 5 indicators: •Income •Employment •Health •Education •Living Environment 5 Deprivation / Density Profile Based on 5 indicators: •Income •Employment •Health •Education • Living Environment Development Principles PROPOSED BUILDINGS > LIBERTY LIFE,FOCUS AROUND MULTI SANDTON CITY SANDTON FUNCTIONAL CENTRES OF ACTIVITY AT REGIONAL AND LOCAL SCALE BARA TRANSPORT FACILITY, SOWETO NEWTOWN MAKING TRANSPORTATION WORK FOR ALL RIDGE WALK TOWARDS STRETFORD STATION BRT AS BACKBONE ILLOVO BOULEVARD BUILD-UP AROUND PUBLIC TRANSPORT NODESVRIVONIA ROADAND FACING LOWDENSGATE CORRIDORS URBAN RESTRUCTURING INVESTMENT IN ADEQUATE INFRASTRUCTURE IN STRATEGIC LOCATIONS -

West Wits Mining MLI (Pty) Ltd, Roodepoort, Johannesburg Metropolitan Municipality, Gauteng Province

West Wits Mining MLI (Pty) Ltd, Roodepoort, Johannesburg Metropolitan Municipality, Gauteng Province Proposed West Wits Mining Project: Various portions of farms, Vogelstruisfontein 231IQ & 233IQ, Roodepoort 236IQ & 237IQ, Vlakfontein 238IQ, Witpoortjie 245IQ, Uitval 677 IQ, Tshekisho 710 IQ, Roodepoort Magisterial District, Gauteng Heritage Impact Assessment Issue Date: 17 May 2019 Revision No.: 0.4 PGS Project No.: 298 HIA + 27 (0) 12 332 5305 +27 (0) 86 675 8077 [email protected] PO Box 32542, Totiusdal, 0134 Offices in South Africa, Kingdom of Lesotho and Mozambique Head Office: 906 Bergarend Streets Waverley, Pretoria, South Africa Directors: HS Steyn, PD Birkholtz, W Fourie Declaration of Independence ▪ I, Jennifer Kitto, declare that – ▪ General declaration: ▪ I act as the independent heritage practitioner in this application; ▪ I will perform the work relating to the application in an objective manner, even if this results in views and findings that are not favourable to the applicant; ▪ I declare that there are no circumstances that may compromise my objectivity in performing such work; ▪ I have expertise in conducting heritage impact assessments, including knowledge of the Act, Regulations and any guidelines that have relevance to the proposed activity; ▪ I will comply with the Act, Regulations and all other applicable legislation; ▪ I will take into account, to the extent possible, the matters listed in section 38 of the National Heritage Resources Act (NHRA) Act 25 of 1999, when preparing the application and any report -

Bibliography

Bibliography Adler, G. and Webster, E. (eds.) (2000) Trade Unions and Democratization in South Africa 1985±1998. London: Macmillan. Adler, J. (1994) `Life in an Informal Settlement'. Urban Forum, vol. 5, no. 2. Altbeker, A. and Steinberg, J. (1998) `Race, Reason and Representation in National Party Discourse, 1990±1992', in D. Howarth and A. Norval, (eds.) South Africa in Transition: New Theoretical Perspectives. London: Macmillan. Althusser, L. (1990) Philosophy and the Spontaneous Philosophy of the Scientists and Other Essays. London: Verso. Anacleti, O. (1990) `African Non-Governmental OrganisationsÐDo They Have a Future?' in Critical Choices for the NGO Community: African Development in the 1990s. Centre for African Studies, University of Edinburgh. ANC (African National Congress). (1980) `Strategies and Tactics', in B. Turok (ed.) Revolutionary Thought in the 20th Century. London: Zed Press. ANC (1985) Kabwe Consultative Conference. Unpublished minutes from the Commissions on Cadre Development and Strategies and Tactics. ANC (1986) `Attack! Attack! Give the Enemy No Quarter. Annual anniversary statement by the national executive committee of the ANC, 8 January 1986'. Sechaba, March edition. ANC (1994) The Reconstruction and Development Programme. Johannesburg: Uma- nyano Publications. Anon. (1985) `Building a tradition of resistance'. Work in Progress, no. 12. Anyang'Nyong'o, P. (ed.) (1987) Popular Struggles for Democracy in Africa. London: Zed Press. Atkinson, D. (1991) `Cities and Citizenship: Towards a Normative Analysis of the Urban Order in South Africa, with Special Reference to East London, 1950±1986'. Ph.D. thesis, University of Natal. Atkinson, D. (1992) `Negotiated Urban Development: Lessons from the Coal Face'. Centre for Policy Studies research report no. -

Memories of Johannesburg, City of Gold © Anne Lapedus

NB This is a WORD document, you are more than Welcome to forward it to anyone you wish, but please could you forward it by merely “attaching” it as a WORD document. Contact details For Anne Lapedus Brest [email protected] [email protected]. 011 783.2237 082 452 7166 cell DISCLAIMER. This article has been written from my memories of S.Africa from 48 years ago, and if A Shul, or Hotel, or a Club is not mentioned, it doesn’t mean that they didn’t exist, it means, simply, that I don’t remember them. I can’t add them in, either, because then the article would not be “My Memories” any more. MEMORIES OF JOHANNESBURG, CITY OF GOLD Written and Compiled By © ANNE LAPEDUS BREST 4th February 2009, Morningside, Sandton, S.Africa On the 4th February 1961, when I was 14 years old, and my brother Robert was 11, our family came to live in Jhb. We had left Ireland, land of our birth, leaving behind our beloved Grandparents, family, friends, and a very special and never-to-be-forgotten little furry friend, to start a new life in South Africa, land of Sunshine and Golden opportunity…………… The Goldeneh Medina…... We came out on the “Edinburgh Castle”, arriving Cape Town 2nd Feb 1961. We did a day tour of Chapmans Peak Drive, Muizenberg, went to somewhere called the “Red Sails” and visited our Sakinofsky/Yodaiken family in Tamboerskloof. We arrived at Park Station (4th Feb 1961), Jhb, hot and dishevelled after a nightmarish train ride, breaking down in De Aar and dying of heat. -

A Case Study on South Africa's First Shipping Container Shopping

Local Public Space, Global Spectacle: A Case Study on South Africa’s First Shipping Container Shopping Center by Tiffany Ferguson BA in Dance BA Interdisciplinary Perspectives on Urban America Hunter College of the City University of New York (2010) Submitted to the Department of Urban Studies and Planning in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master in City Planning at the MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY June 2018 © 2018 Tiffany Ferguson. All Rights Reserved The author hereby grants to MIT the permission to reproduce and to distribute publicly paper and electronic copies of the thesis document in whole or in part in any medium now known or hereafter created. Author____________________________________________________________________ Department of Urban Studies and Planning May 24, 2018 Certified by_________________________________________________________________ Assistant Professor of Political Economy and Urban Planning, Jason Jackson Department of Urban Studies and Planning Thesis Supervisor Accepted by________________________________________________________________ Professor of the Practice, Ceasar McDowell Department of Urban Studies and Planning Chair, MCP Committee 2 Local Public Space, Global Spectacle: A Case Study on South Africa’s First Shipping Container Shopping Center by Tiffany Ferguson Submitted to the Department of Urban Studies and Planning on May 24, 2018 in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master in City Planning Abstract This thesis is the explication of a journey to reconcile Johannesburg’s aspiration to become a ‘spatially just world class African city’ through the lens of the underperforming 27 Boxes, a globally inspired yet locally contested retail center in the popular Johannesburg suburb of Melville. By examining the project’s public space, market, retail, and design features – features that play a critical role in its imagined local economic development promise – I argue that the project’s ‘failure’ can be seen through a prism of factors that are simultaneously local and global. -

Exploring the Applicability of Location-Based Services to Delineate the State Public Transport Routes Integratedness Within the City of Johannesburg

infrastructures Review Exploring the Applicability of Location-Based Services to Delineate the State Public Transport Routes Integratedness within the City of Johannesburg Brightnes Risimati 1,* and Trynos Gumbo 2 1 Department of Quality and Operations Management, University of Johannesburg, Corner of Siemert and Beit Streets, Doornfontein, Johannesburg 2028, South Africa 2 Department of Town and Regional Planning, University of Johannesburg, Corner of Siemert and Beit Streets, Doornfontein, Johannesburg 2028, South Africa; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +27-783-326-246 Received: 30 May 2018; Accepted: 25 July 2018; Published: 1 August 2018 Abstract: In the past decade, Johannesburg has actively participated in the investment and development of the Gautrain and Rea Vaya public transportation modes. However, the state of route networks connectedness amongst the two public transport modes has not been well documented. Thus, this study aimed to delineate the extent of routes network integration among the two modes. The study adopted a phenomenological case study survey design which applied a mixed-method approach to gather spatial, qualitative and quantitative data. Crowd sourced datasets from Facebook and Twitter were collected, and analyzed using the kriging interpolation method and descriptive statistics. Key informant interviews were also used to unpack the status quo of the two modes. Results indicate that there are limited areas where the route networks between the two modes are currently integrated. Variations in income levels may be a factor currently preventing inter-transfer between the two modes. The Rea Vaya has proven successful in improving accessibility to economic opportunities, with 70% of the social media posts reflecting positive views regarding route and travel timetables.