Economic Development Strategies Aimed at Boosting Employment

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Transforming the Springboks: Re-Imagining the South African Nation Through Sport

This paper is a post-print of an article published in Social Dynamics 29:1 (2003): 27-48. The definitive version is available at: http://www.africanstudies.uct.ac.za/downloads/29_1farquharson.zip Transforming the Springboks: Re-imagining the South African Nation through Sport 1 Karen Farquharson and Timothy Marjoribanks Abstract Nation-building occurs not only through the creation of formal institutions, but also through struggles in cultural and symbolic contexts. In apartheid South Africa, the rugby union Springboks both symbolised and institutionalised a racially based form of ‘bounded citizenship’. In post-apartheid South Africa, the Springboks have emerged as a contested and significant site in the attempt to build a non-racial nation through reconciliation. To explore these contests, we undertook a qualitative thematic analysis of newspaper discourses around the Springboks, reconciliation and nation-building in the contexts of the 1995 and 1999 Rugby World Cups. Our research suggests, first, that the Springboks have been re-imagined in newspaper discourses as a symbol of the non-racial nation-building process in South Africa, especially in ‘media events’ such as the World Cup. Second, we find that there are significant limitations in translating this symbolism into institutionalised practice, as exemplified by newspaper debates over the place of ‘merit’ in international team selection processes. We conclude that the media framing of the role of the Springboks in nation-building indicates that unless the re-imagination of the Springboks is accompanied by a transformation in who is selected to represent the team, and symbolically the nation, the Springboks’ contribution to South African nation-building will be over. -

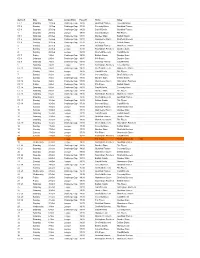

Coventry Blaze Fixtures 18/19

COVENTRY BLAZE FIXTURES 18/19 Day Date Month Home or Away Opposition Competition Face-Off Saturday 25 August Away Cardiff Devils Pre-Season 7.00pm Sunday 26 August Home Cardiff Devils Pre-Season 5.15pm Wednesday 29 August Home Milton Keynes Lightning Pre-Season 7.30pm Saturday 1 September Home Amiens Gothiques Pre-Season 7.00pm Sunday 2 September Home Amiens Gothiques Pre-Season 5.15pm Wednesday 5 September Away Milton Keynes Lightning Pre-Season 7.30pm Saturday 8 September Away Guildford Flames Challenge Cup 6.00pm Sunday 9 September Home Guildford Flames Challenge Cup 5.15pm Saturday 15 September Away Milton Keynes Lightning Challenge Cup 7.00pm Sunday 16 September Home Nottingham Panthers Elite League 5.15pm Saturday 22 September Away Cardiff Devils Challenge Cup 7.00pm Sunday 23 September Home Milton Keynes Lightning Elite League 5.15pm Saturday 29 September Home Glasgow Clan Elite League 7.00pm Sunday 30 September Home Sheffield Steelers Elite League 5.15pm Saturday 6 October Away Nottingham Panthers Elite League 7.00pm Sunday 7 October Home Belfast Giants Elite League 5.15pm Saturday 13 October Away Manchester Storm Elite League 7.00pm Sunday 14 October Home Manchester Storm Elite League 5.15pm Saturday 20 October Away Glasgow Clan Elite League 7.00pm Sunday 21 October Home Milton Keynes Lightning Challenge Cup 5.15pm Saturday 27 October Away Fife Flyers Elite League 7.15pm Sunday 28 October Home Cardiff Devils Challenge Cup 5.15pm Wednesday 31 October Away Sheffield Steelers Elite League 7.30pm Saturday 3 November Away Cardiff -

INSIDE... Editor’S Letter

Club Journal October 2018 The magazine for all CIU members 75 p Union members enjoy a night out at Sheffield Dogs INSIDE... Editor’s Letter . 2 Club News . 3 CIU Racing Club . 9 Club of the Month . 11 HQ . 14 Club Outings . 18 Union General Secretary Kenneth D Green CMD (2nd 21 from right) and Dransfields Crossword . Managing Director Chris Haley (2nd from left) make a presentation to a race winner Hundreds of CIU members enjoyed the 2018 Central Club Stakes. Dransfields CIU Greyhound Racenight held Union General Secretary Kenneth D Green at Sheffield’s Owlerton Stadium on Tuesday, CMD said: “It was another great night out at September 18. Owlerton Stadium and it was very pleasing to e annual event saw a number of CIU see so many CIU people enjoying the food and officials in attendance, including General hospitality. Secretary Kenneth D Green CMD, President “ank you to all the clubs who came along George Dawson CMD and NEC members and to the suppliers who sponsored races on John Batchelor and Les Hepworth CMD. the night.” ere was some thrilling action out on the e CIU Greyhound Sweepstake was won Club of the Month: track with a total of 14 races taking place by New Silkworth RBL Club and West Oxford throughout the evening, including the Democrats Club who both selected Heat 5, Rossington Labour Dransfields Sheffield Stadium Sprint, the ABV Trap 6. Wholesalers Stakes, the Beerpiper Ltd Race, e clubs shared the prize money of £1,200 & Social Club the Chemisphere UK Race and the Barnsley between them. -

Dinnington Newsletter Online

Dinnington High School Newsletter Contents Welcome School News We hope you enjoy our latest newsletter! As wrappers and cutlery, instead of plastics. We ever, I am immensely proud of all that our have recycling bins for paper and cans. We are students achieve in so many different ways and also in the middle of a big project to have new Rewards Ceremonies 04 the support they receive from their teachers. boilers (for which we got a grant) so we should Almost weekly, we are wishing good luck to be more efficient at keeping our school warm. Normandy 04 students who take part in such an array of sporting, dance and racing activities. This We finished the year with a fabulous Sports The BIG Show 05 newsletter provides just a small glimpse of all Presentation, Rewards trips, Celebration Fundraising 05 that our awesome students do. Assemblies, foreign trips, Sports Day, Duke of Edinburgh and, in the last week, a whole week World Book Day 06 There is always an array of highlights for us to with our new Y6 students. We never have a Kindness & Co 06 reflect on each year. One of my annual quiet week at Dinnington as we strive to give favourites is the ‘Random Act of Kindness Week’ students a wide range of experiences to Transition 07 (or three weeks as it is at Dinnington). A huge enhance their learning. Results Day 10 thanks to those of you who supported the effort by sending cans for the food bank or As ever, we remain hugely appreciative of your warm things for the Cathedral homeless project. -

2019 Tokyo Marathon Statistical Information

2019 Tokyo Marathon Statistical Information Tokyo Marathon All Time list Performance Time Performers Name Nat Place Date 1 2:03:58 1 Wilson Kipsang KEN 1 26 Feb 2017 2 2:05:30 2 Dickson Chumba KEN 1 25 Feb 2018 3 2:05:42 Dickson Chumba 1 23 Feb 2014 4 2:05:51 3 Gideon Kipketer KEN 2 26 Feb 2017 5 2:05:57 4 Tadese Tola ETH 2 23 Feb 2014 6 2:06:00 5 Endeshaw Negesse ETH 1 22 Feb 2015 7 2:06:11 6 Yuta Shitara JPN 2 25 Feb 2018 8 2:06:25 Dickson Chumba 3 26 Feb 2017 9 2:06:30 7 Sammy Kitwara KEN 3 23 Feb 2014 10 2:06:33 8 Stephen Kiprotich UGA 2 22 Feb 2015 11 2:06:33 9 Amos Kipruto KEN 3 25 Feb 2018 12 2:06:34 Dickson Chumba 3 22 Feb 2015 13 2:06:42 10 Evans Chebet KEN 4 26 Feb 2017 14 2:06:47 Gideon Kipketer 4 25 Feb 2018 15 2:06:50 11 Dennis Kimetto KEN 1 24 Feb 2013 16 2:06:54 12 Hiroto Inoue JPN 5 25 Feb 2018 17 2:06:56 13 Feyisa Lilesa ETH 1 28 Feb 2016 18 2:06:58 14 Michael Kipyego KEN 2 24 Feb 2013 19 2:06:58 Michael Kipyego 4 23 Feb 2014 20 2:07:05 15 Peter Some KEN 5 23 Feb 2014 21 2:07:20 16 Shumi Dechasa BRN 4 22 Feb 2015 22 2:07:22 Peter Some 5 22 Feb 2015 23 2:07:23 17 Viktor Röthlin SUI 1 17 Feb 2008 24 2:07:25 18 Markos Geneti ETH 6 22 Feb 2015 25 2:07:30 Feyisa Lilesa 6 25 Feb 2018 26 2:07:33 19 Bernard Kipyego KEN 2 28 Feb 2016 27 2:07:34 Dickson Chumba 3 28 Feb 2016 28 2:07:35 20 Hailu Mekonnen ETH 1 27 Feb 2011 29 2:07:37 Michael Kipyego 1 26 Feb 2012 30 2:07:37 21 Geoffrey Kamworor Kipsang KEN 6 23 Feb 2014 31 2:07:39 22 Masato Imai JPN 7 22 Feb 2015 32 2:07:39 23 Alfers Lagat KEN 5 26 Feb 2017 33 2:07:40 24 Deresa Chimsa -

2007 – a New Dawn When Young Stars Will Emerge

UPDATE Newsletter of the European Athletic Association 4|06 December European Athletic Association | Avenue Louis-Ruchonnet 18 | 1003 Lausanne (Switzerland) Phone +41 (21) 313 43 50 | Fax +41 (21) 313 43 51 | Email offi [email protected] | www.european-athletics.org Message from European Athletics President Hansjörg Wirz 2007 – A new dawn when young stars will emerge We come to the end of another successful These events play a crucial part in the year for European Athletics and we can look development of our sport and it is no surprise back on the season gone by, the highlight of to see that Christian Olsson, Susanna Kallur which was the best ever European Athletics and Yelena Isinbayeva, who were all crowned Championships, with a great deal of pride. European Champions in Gothenburg last summer, were all previous champions at U23 The year began with the European Athletics level. Indoor Cup in front of a full house in Lievin, France, on the fi rst weekend of March. It has long been the policy of European The men’s competition, which was won Athletics, to focus our fi nancial resources by the host nation, went down to the fi nal into these “developmental” competitions event and in the end could have been won and ensure that there is an appropriate level by any one of four nations. For me, this of competitions for Europe’s young athletes weekend epitomised what makes our Cup at an important stage in their physical competitions so special: teamwork, national development. I have no doubt that a number passion, togetherness and above all, a sense of future champions at senior level will be of unpredictability about the end result! on show in Debrecen and Hengelo next summer. -

Annual Report 2019 2 Newcastle Eagles Community Foundation

ANNUAL REPORT 2019 2 NEWCASTLE EAGLES COMMUNITY FOUNDATION FACTS AND FIGURES 2018-19 schools 81 participated 7,048 young people extra-curricular school9 clubs 6 1 took part established within the council champion of East End of Newcastle finals champions final 419 all the BBL squad players deliver Hoops 4 Health roadshows young people have attended 0 3 times club teams compete or more within our junior 76 central venue league 72 OVER OVER players club or after 49 school sites 2,000 800 attending competing in 5 to 9 clubs our central years olds every venue league 12 week every week officiating receiving staff for CVL 1,500 coaching more than foundation school club sites 7 trustees 22 across the region full time 7,000 staff volunteer hours 9 part time donated this season 40 staff zero our clubs cater from 5 years old to senior age groups core-funding ANNUAL REPORT 2019 3 INTRODUCTION 2018-19 was a landmark year for the Eagles Community Foundation, with a long term vision realised when we all moved into the Eagles Community Arena (ECA). It is impossible to properly articulate in these pages the gratitude to all past and present employees, partners, sponsors, funders, and volunteers who have made this possible. 2018/19 has seen us continue the fine work across the community and in schools, and the most exciting development of all has been the capacity we have as an organization to now host all of our holiday camps, tournaments, leagues and events at our own facility. All of our users have benefited from the outstanding facilities, and we are continually building bridges across the entire North East community to grow our provision, delivery and the opportunities for all interested in sport. -

Plymouth Raiders V DBL Sharks Sheffield

GAME PACK Plymouth Raiders v DBL Sharks Sheffield Sunday 4 February 2018 4:00 PM BBL Championship Plymouth Pavillions Head to Head Plymouth Raiders DBL Sharks Sheffield Overall: Championship 13 30 Trophy 0 4 Cup 1 1 Play Offs 1 0 Total 15 35 Home: Championship 9 18 Trophy 0 1 Cup 0 1 Play Offs 1 0 Total 10 20 Away: Championship 4 12 Trophy 0 3 Cup 1 0 Play Offs 0 0 Total 5 15 @ Neutral Venue: Championship 0 0 Trophy 0 0 Cup 0 0 Play Offs 0 0 Total 0 0 Last 10 Matches: 4 6 Biggest Win by 29 point(s) 02/10/16 @ EIS Sheffield by 43 point(s) 01/10/10 @ EIS Sheffield 95-66 BBL Championship 116-73 BBL Championship Last Win by 29 point(s) 02/10/16 @ EIS Sheffield by 5 point(s) 13/10/17 @ EIS Sheffield 95-66 BBL Championship 83-78 BBL Championship Past Meetings Plymouth Raiders v DBL Sharks Sheffield 2017/2018 29/04/2018 CH Plymouth Pavillions Plymouth Raiders - Sheffield Sharks 04/02/2018 CH Plymouth Pavillions Plymouth Raiders - Sheffield Sharks 13/10/2017 CH EIS Sheffield Sheffield Sharks 83- 78 Plymouth Raiders 2016/2017 05/03/2017 CH Plymouth Pavillions Plymouth Raiders 81- 87 Sheffield Sharks 25/11/2016 CH EIS Sheffield Sheffield Sharks 87- 78 Plymouth Raiders 02/10/2016 CH EIS Sheffield Sheffield Sharks 66- 95 Plymouth Raiders 2015/2016 17/04/2016 CH Plymouth Pavillions Plymouth Raiders 84- 76 Sheffield Sharks 04/03/2016 CH Plymouth Pavillions Plymouth Raiders 82- 77 Sheffield Sharks 31/01/2016 TRO Quarter Finals Plymouth Pavillions Plymouth Raiders 73- 99 Sheffield Sharks 29/01/2016 CH EIS Sheffield Sheffield Sharks 74- 68 Plymouth Raiders -

2021/22 Schedule

Game # Day Date Competition Faceoff Home Away CC 1 Saturday 18-Sep Challenge Cup 18:00 Guildford Flames Coventry Blaze CC 2 Sunday 19-Sep Challenge Cup 17:30 Coventry Blaze Guildford Flames CC 3 Saturday 25-Sep Challenge Cup 19:00 Cardiff Devils Guildford Flames 1 Saturday 25-Sep League 19:00 Coventry Blaze Fife Flyers CC 4 Saturday 25-Sep Challenge Cup 19:00 Dundee Stars Belfast Giants CC 5 Saturday 25-Sep Challenge Cup 19:00 Manchester Storm Sheffield Steelers CC 6 Sunday 26-Sep Challenge Cup 17:30 Fife Flyers Belfast Giants 2 Sunday 26-Sep League 18:00 Guildford Flames Manchester Storm 3 Sunday 26-Sep League 16:00 Nottingham Panthers Dundee Stars 4 Sunday 26-Sep League 16:00 Sheffield Steelers Cardiff Devils CC 7 Friday 1-Oct Challenge Cup 19:00 Belfast Giants Dundee Stars CC 8 Saturday 2-Oct Challenge Cup 19:15 Fife Flyers Dundee Stars CC 9 Saturday 2-Oct Challenge Cup 18:00 Guildford Flames Cardiff Devils 5 Saturday 2-Oct League 19:00 Nottingham Panthers Coventry Blaze CC 10 Saturday 2-Oct Challenge Cup 19:00 Sheffield Steelers Manchester Storm 6 Sunday 3-Oct League 18:00 Cardiff Devils Fife Flyers 7 Sunday 3-Oct League 17:30 Coventry Blaze Sheffield Steelers CC 11 Sunday 3-Oct Challenge Cup 17:00 Dundee Stars Belfast Giants CC 12 Sunday 3-Oct Challenge Cup 17:30 Manchester Storm Nottingham Panthers CC 13 Friday 8-Oct Challenge Cup 19:30 Fife Flyers Belfast Giants CC 14 Saturday 9-Oct Challenge Cup 19:00 Cardiff Devils Coventry Blaze CC 15 Saturday 9-Oct Challenge Cup 19:00 Dundee Stars Fife Flyers CC 16 Saturday 9-Oct Challenge Cup -

Tale of Cities Tale of C

TaleTale of citiesc A practitioner’s guide to city recovery By Anne Power, Astrid Winkler, Jörg Plöger and Laura Lane 2 Contents Introduction 4 Industrial cities in their hey-day 5 Historic roles 6 Industrial giants 8 Industrial pressures 14 Industrial collapse and its consequences 15 Economic and social unravelling 16 Cumulative damage and the failures of mass housing 18 Inner city abandonment 24 Surburbanisation 26 Political unrest 27 Unwanted industrial infrastructure 28 New perspectives, new ideas, new roles 31 Symbols of change 32 Big ideas 35 New enterprises 36 Massive physical reinvestment by cities, 37 governments and EU Restored cities 38 New transport links 47 Practical steps towards recovery 49 Building the new economy 50 – Saint-Étienne’s Design Village and the survival of small workshops – Sheffi eld’s Advanced Science Park and Cultural Industries Quarter – Bremen’s technology focus – Torino’s incubators for local entrepreneurs – Belfast’s innovative reuse of former docks – Leipzig’s new logistics and manufacturing centres Building social enterprise and integration 60 Building skills 64 Upgrading local environments 67 Working in partnership with local communities 71 Have the cities turned the corner? 75 New image through innovative use of existing assets 76 Where next for the seven cities? 81 An uncertain future 82 Conclusion 84 Appendix 85 3 Introduction This documentary booklet traces at ground level social and economic in the seven cities and elsewhere with suggestions and comments. progress of seven European cities observing dramatic changes in Our contact details can be found at the back of the document. We industrial and post-industrial economies, their booming then shrinking know that we have not done justice to the scale of work that has gone populations, their employment and political leadership. -

Sheffield & Rotherham Joint Employment Land Review Final

Sheffield & Rotherham Joint Employment Land Review Final Report Sheffield City Council and Rotherham Metropolitan Borough Council 15 October 2015 50467/JG/RL Nathaniel Lichfield & Partners Generator Studios Trafalgar Street Newcastle NE1 2LA nlpplanning.com This document is formatted for double sided printing. © Nathaniel Lichfield & Partners Ltd 2015. Trading as Nathaniel Lichfield & Partners. All Rights Reserved. Registered Office: 14 Regent's Wharf All Saints Street London N1 9RL All plans within this document produced by NLP are based upon Ordnance Survey mapping with the permission of Her Majesty’s Stationery Office. © Crown Copyright reserved. Licence number AL50684A Sheffield & Rotherham Joint Employment Land Review : Final Report Contents 1.0 Introduction 1 Scope of Study................................................................................................. 1 Methodology .................................................................................................... 2 Structure of the Report ..................................................................................... 3 2.0 Policy Review 5 National Documents ......................................................................................... 5 Sub-Regional Documents ................................................................................ 8 Rotherham Documents .................................................................................. 10 Sheffield Documents ..................................................................................... -

Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} Sky's the Limit British Cycling's Quest To

Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} Sky's the Limit British Cycling's Quest to Conquer the Tour de France by Richard Moore Sky's the Limit: Wiggins and Cavendish: the Quest to Conquer the Tour de France: Cavendish and Wiggins: The Quest to Conquer the Tour deFrance. Sky's the Limit On Sunday 22 July, Bradley Wiggins became the first British rider ever to win the Tour de France. It was the culmination of years of hard work and dedication and a vision begun with the creation of Team Sky. This is the inside story of that journey to greatness. Full description. "synopsis" may belong to another edition of this title. Richard Moore, whose excellent Heroes, Villains And Velodromes chronicled Britain's success in Beijing, was given generous access by Brailsford and Team Sky, but this is not an authorised book and is all the better for that. His well-informed, pacy account of last year's debut season has the twists and turns of a thriller, because things did not go to plan. --Independent on Sunday. About the Author : Richard Moore is a freelance journalist who has written on sport, art and literature, contributing to the Scotsman, Scotland on Sunday, Herald, Guardian and Sunday Times. He was a member of the Scotland team in the Prutour, the nine-day cycling tour of Britain, and represented Scotland in the 1998 Commonwealth Games. His first book for HarperSport, In Search of Robert Millar, won Best Biography at the 2007 British Sports Book Awards. His Heroes, Villains and Velodromes was a bestseller for HarperSport in 2008, and in 2009 he ghosted Chris Hoy's autobiography.