A Global Survey of Current Zoo Housing and Husbandry Practices for Fossa: a Preliminary Review

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

VII. Bodies, Institutes and Centres

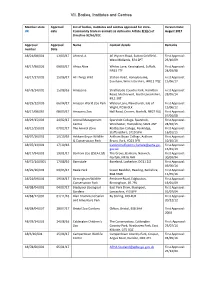

VII. Bodies, Institutes and Centres Member state Approval List of bodies, institutes and centres approved for intra- Version Date: UK date Community trade in animals as defined in Article 2(1)(c) of August 2017 Directive 92/65/EEC Approval Approval Name Contact details Remarks number Date AB/21/08/001 13/03/17 Ahmed, A 46 Wyvern Road, Sutton Coldfield, First Approval: West Midlands, B74 2PT 23/10/09 AB/17/98/026 09/03/17 Africa Alive Whites Lane, Kessingland, Suffolk, First Approval: NR33 7TF 24/03/98 AB/17/17/005 15/06/17 All Things Wild Station Road, Honeybourne, First Approval: Evesham, Worcestershire, WR11 7QZ 15/06/17 AB/78/14/002 15/08/16 Amazonia Strathclyde Country Park, Hamilton First Approval: Road, Motherwell, North Lanarkshire, 28/05/14 ML1 3RT AB/29/12/003 06/04/17 Amazon World Zoo Park Watery Lane, Newchurch, Isle of First Approval: Wight, PO36 0LX 15/06/12 AB/17/08/065 08/03/17 Amazona Zoo Hall Road, Cromer, Norfolk, NR27 9JG First Approval: 07/04/08 AB/29/15/003 24/02/17 Animal Management Sparsholt College, Sparsholt, First Approval: Centre Winchester, Hampshire, SO21 2NF 24/02/15 AB/12/15/001 07/02/17 The Animal Zone Rodbaston College, Penkridge, First Approval: Staffordshire, ST19 5PH 16/01/15 AB/07/16/001 10/10/16 Askham Bryan Wildlife Askham Bryan College, Askham First Approval: & Conservation Park Bryan, York, YO23 3FR 10/10/16 AB/07/13/001 17/10/16 [email protected]. First Approval: gov.uk 15/01/13 AB/17/94/001 19/01/17 Banham Zoo (ZSEA Ltd) The Grove, Banham, Norwich, First Approval: Norfolk, NR16 -

Table 7: Species Changing IUCN Red List Status (2014-2015)

IUCN Red List version 2015.4: Table 7 Last Updated: 19 November 2015 Table 7: Species changing IUCN Red List Status (2014-2015) Published listings of a species' status may change for a variety of reasons (genuine improvement or deterioration in status; new information being available that was not known at the time of the previous assessment; taxonomic changes; corrections to mistakes made in previous assessments, etc. To help Red List users interpret the changes between the Red List updates, a summary of species that have changed category between 2014 (IUCN Red List version 2014.3) and 2015 (IUCN Red List version 2015-4) and the reasons for these changes is provided in the table below. IUCN Red List Categories: EX - Extinct, EW - Extinct in the Wild, CR - Critically Endangered, EN - Endangered, VU - Vulnerable, LR/cd - Lower Risk/conservation dependent, NT - Near Threatened (includes LR/nt - Lower Risk/near threatened), DD - Data Deficient, LC - Least Concern (includes LR/lc - Lower Risk, least concern). Reasons for change: G - Genuine status change (genuine improvement or deterioration in the species' status); N - Non-genuine status change (i.e., status changes due to new information, improved knowledge of the criteria, incorrect data used previously, taxonomic revision, etc.); E - Previous listing was an Error. IUCN Red List IUCN Red Reason for Red List Scientific name Common name (2014) List (2015) change version Category Category MAMMALS Aonyx capensis African Clawless Otter LC NT N 2015-2 Ailurus fulgens Red Panda VU EN N 2015-4 -

Verzeichnis Der Europäischen Zoos Arten-, Natur- Und Tierschutzorganisationen

uantum Q Verzeichnis 2021 Verzeichnis der europäischen Zoos Arten-, Natur- und Tierschutzorganisationen Directory of European zoos and conservation orientated organisations ISBN: 978-3-86523-283-0 in Zusammenarbeit mit: Verband der Zoologischen Gärten e.V. Deutsche Tierpark-Gesellschaft e.V. Deutscher Wildgehege-Verband e.V. zooschweiz zoosuisse Schüling Verlag Falkenhorst 2 – 48155 Münster – Germany [email protected] www.tiergarten.com/quantum 1 DAN-INJECT Smith GmbH Special Vet. Instruments · Spezial Vet. Geräte Celler Str. 2 · 29664 Walsrode Telefon: 05161 4813192 Telefax: 05161 74574 E-Mail: [email protected] Website: www.daninject-smith.de Verkauf, Beratung und Service für Ferninjektionsgeräte und Zubehör & I N T E R Z O O Service + Logistik GmbH Tranquilizing Equipment Zootiertransporte (Straße, Luft und See), KistenbauBeratung, entsprechend Verkauf undden Service internationalen für Ferninjektionsgeräte und Zubehör Vorschriften, Unterstützung bei der Beschaffung der erforderlichenZootiertransporte Dokumente, (Straße, Vermittlung Luft und von See), Tieren Kistenbau entsprechend den internationalen Vorschriften, Unterstützung bei der Beschaffung der Celler Str.erforderlichen 2, 29664 Walsrode Dokumente, Vermittlung von Tieren Tel.: 05161 – 4813192 Fax: 05161 74574 E-Mail: [email protected] Str. 2, 29664 Walsrode www.interzoo.deTel.: 05161 – 4813192 Fax: 05161 – 74574 2 e-mail: [email protected] & [email protected] http://www.interzoo.de http://www.daninject-smith.de Vorwort Früheren Auflagen des Quantum Verzeichnis lag eine CD-Rom mit der Druckdatei im PDF-Format bei, welche sich großer Beliebtheit erfreute. Nicht zuletzt aus ökologischen Gründen verzichten wir zukünftig auf eine CD-Rom. Stattdessen kann das Quantum Verzeichnis in digitaler Form über unseren Webshop (www.buchkurier.de) kostenlos heruntergeladen werden. Die Datei darf gerne kopiert und weitergegeben werden. -

Dental and Temporomandibular Joint Pathology of the Kit Fox (Vulpes Macrotis)

Author's Personal Copy J. Comp. Path. 2019, Vol. 167, 60e72 Available online at www.sciencedirect.com ScienceDirect www.elsevier.com/locate/jcpa DISEASE IN WILDLIFE OR EXOTIC SPECIES Dental and Temporomandibular Joint Pathology of the Kit Fox (Vulpes macrotis) N. Yanagisawa*, R. E. Wilson*, P. H. Kass† and F. J. M. Verstraete* *Department of Surgical and Radiological Sciences and † Department of Population Health and Reproduction, School of Veterinary Medicine, University of California, Davis, California, USA Summary Skull specimens from 836 kit foxes (Vulpes macrotis) were examined macroscopically according to predefined criteria; 559 specimens were included in this study. The study group consisted of 248 (44.4%) females, 267 (47.8%) males and 44 (7.9%) specimens of unknown sex; 128 (22.9%) skulls were from young adults and 431 (77.1%) were from adults. Of the 23,478 possible teeth, 21,883 teeth (93.2%) were present for examina- tion, 45 (1.9%) were absent congenitally, 405 (1.7%) were acquired losses and 1,145 (4.9%) were missing ar- tefactually. No persistent deciduous teeth were observed. Eight (0.04%) supernumerary teeth were found in seven (1.3%) specimens and 13 (0.06%) teeth from 12 (2.1%) specimens were malformed. Root number vari- ation was present in 20.3% (403/1,984) of the present maxillary and mandibular first premolar teeth. Eleven (2.0%) foxes had lesions consistent with enamel hypoplasia and 77 (13.8%) had fenestrations in the maxillary alveolar bone. Periodontitis and attrition/abrasion affected the majority of foxes (71.6% and 90.5%, respec- tively). -

BIERZS 2007 Program and Abstracts

BIERZS 2007 Bear Information Exchange for Rehabilitators, Zoos & Program and Abstracts and Program Sanctuaries 24th - 26th August 2007 Pomona, CA BIERZS 2007 Welcome Dear BIERZS Delegate, Welcome Delegates ....................... 2 The BIERZS 2007 Planning Group, Sponsors, BIERZS 2007 Sponsors . 2-3 and Volunteers want to welcome you to the first international bear care symposium for Contents Planning Group ............................. 4 rehabilitator, zoo, and sanctuary bear care professionals. Our objective is to exchange Venue Information and Maps........ 5-8 bear care information, ideas and issues, and to build bridges of communication between our General Information ....................... 9 organizations in order maximize our strengths and resources in bear care and bear Volunteer Appreciation................. 10 conservation. This weekend you will enjoy three terrific venues, stimulating Egg Breaker ................................ 11 presentations, hands-on workshops, good food, new friends and excellent conversation. Program/Abstracts .................. 12-52 Thank you for participating and have fun. JOIN !!!! www.bearkeepers.net Poster Abstracts..................... 53-58 BIERZS 2007-Evaluation ......... 59-61 Sponsors · Animals Asia · AZA Bear Taxon Advisory Group · Carol J. McIntyre · Direct Medical Systems Direct Medical Systems-Portable Ultrasound · Friends Of The Moonridge Animal Park · International Wildlife Rehabilitation Council · Los Angeles Zoo and Botanical Gardens AZA BEAR TAG BIERZS 2007 Sponsors · Pet Ag · Polar -

ATIC0943 {By Email}

Animal and Plant Health Agency T 0208 2257636 Access to Information Team F 01932 357608 Weybourne Building Ground Floor Woodham Lane www.gov.uk/apha New Haw Addlestone Surrey KT15 3NB Our Ref: ATIC0943 {By Email} 4 October 2016 Dear PROVISION OF REQUESTED INFORMATION Thank you for your request for information about zoos which we received on 26 September 2016. Your request has been handled under the Freedom of Information Act 2000. The information you requested and our response is detailed below: “Please can you provide me with a full list of the names of all Zoos in the UK. Under the classification of 'Zoos' I am including any place where a member of the public can visit or observe captive animals: zoological parks, centres or gardens; aquariums, oceanariums or aquatic attractions; wildlife centres; butterfly farms; petting farms or petting zoos. “Please also provide me the date of when each zoo has received its license under the Zoo License act 1981.” See Appendix 1 for a list that APHA hold on current licensed zoos affected by the Zoo License Act 1981 in Great Britain (England, Scotland and Wales), as at 26 September 2016 (date of request). The information relating to Northern Ireland is not held by APHA. Any potential information maybe held with the Department of Agriculture, Environment and Rural Affairs Northern Ireland (DAERA-NI). Where there are blanks on the zoo license start date that means the information you have requested is not held by APHA. Please note that the Local Authorities’ Trading Standard departments are responsible for administering and issuing zoo licensing under the Zoo Licensing Act 1981. -

The Impact of Forest Logging and Fragmentation on Carnivore Species Composition, Density and Occupancy in Madagascar’S Rainforests

The impact of forest logging and fragmentation on carnivore species composition, density and occupancy in Madagascar’s rainforests B RIAN D. GERBER,SARAH M. KARPANTY and J OHNY R ANDRIANANTENAINA Abstract Forest carnivores are threatened globally by Introduction logging and forest fragmentation yet we know relatively little about how such change affects predator populations. arnivores are one of the most threatened groups of 2009 This is especially true in Madagascar, where carnivores Cterrestrial mammals (Karanth & Chellam, ). have not been extensively studied. To understand better the Declines of predators are often attributed to habitat loss effects of logging and fragmentation on Malagasy carnivores and fragmentation but few quantitative studies have we evaluated species composition, density of fossa examined how carnivore populations and communities 2002 Cryptoprocta ferox and Malagasy civet Fossa fossana, and change with habitat loss or fragmentation (Crooks, ; 2005 carnivore occupancy in central-eastern Madagascar. We Michalski & Peres, ). This is particularly true for ’ photographically-sampled carnivores in two contiguous Madagascar s carnivores, with knowledge lacking about ff (primary and selectively-logged) and two fragmented rain- their ecology and the e ects of anthropogenic disturbances 2010 forests (fragments , 2.5 and . 15 km from intact forest). (Irwin et al., ), especially in the eastern rainforest where Species composition varied, with more native carnivores in only short-term studies have been conducted (Gerber et al., 2010 16 the contiguous than fragmented rainforests. F. fossana was ). With only % of the original primary forests extant absent from fragmented rainforests and at a lower density in Madagascar and those remaining becoming smaller and 2007 in selectively-logged than in primary rainforest (mean more isolated over time (Harper et al., ), habitat loss −2 1.38 ± SE 0.22 and 3.19 ± SE 0.55 individuals km , respect- and fragmentation are serious threats to many endemic 2010 ively). -

An Educator's Resource to Texas Mammal Skulls and Skins

E4H-014 11/17 An Educator’s Resource to Texas Mammal Skulls and Skins for use in 4-H Wildlife Programs and FFA Wildlife Career Development Events By, Denise Harmel-Garza Program Coordinator I, Texas A&M AgriLife Extension Service, 4-H Photographer and coauthor, Audrey Sepulveda M.Ed. Agricultural Leadership, Education and Communications, Texas A&M University College Station, Texas 2017 “A special thanks to the Biodiversity Research and Teaching Collections at Texas A&M University for providing access to their specimens.” Texas A&M AgriLife Extension provides equal opportunities in its programs and employment to all persons, regardless of race, color, sex, religion, national origin, disability, age, genetic information, veteran status, sexual orientation, or gender identity. The Texas A&M University System, U.S. Department of Agriculture, and the County Commissioners Courts of Texas Cooperating. Introduction Texas youth that participate in wildlife programs may be asked to identify a skull, skin, scat, tracks, etc. of an animal. Usually, educators must find this information and assemble pictures of skulls and skins from various sources. They also must ensure that what they find is relevant and accurate. Buying skulls and skins to represent all Texas mammals is costly. Most educators cannot afford them, and if they can, maintaining these collections over time is problematic. This study resource will reduce the time teachers across the state need to spend searching for information and allow them more time for presenting the material to their students. This identification guide gives teachers and students easy access to information that is accurate and valuable for learning to identify Texas mammals. -

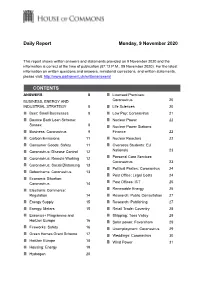

Daily Report Monday, 9 November 2020 CONTENTS

Daily Report Monday, 9 November 2020 This report shows written answers and statements provided on 9 November 2020 and the information is correct at the time of publication (07:12 P.M., 09 November 2020). For the latest information on written questions and answers, ministerial corrections, and written statements, please visit: http://www.parliament.uk/writtenanswers/ CONTENTS ANSWERS 8 Licensed Premises: BUSINESS, ENERGY AND Coronavirus 20 INDUSTRIAL STRATEGY 8 Life Sciences 20 Beer: Small Businesses 8 Low Pay: Coronavirus 21 Bounce Back Loan Scheme: Nuclear Power 22 Sussex 8 Nuclear Power Stations: Business: Coronavirus 9 Finance 22 Carbon Emissions 11 Nuclear Reactors 22 Consumer Goods: Safety 11 Overseas Students: EU Coronavirus: Disease Control 12 Nationals 23 Coronavirus: Remote Working 12 Personal Care Services: Coronavirus 23 Coronavirus: Social Distancing 13 Political Parties: Coronavirus 24 Debenhams: Coronavirus 13 Post Office: Legal Costs 24 Economic Situation: Coronavirus 14 Post Offices: ICT 25 Electronic Commerce: Renewable Energy 25 Regulation 14 Research: Public Consultation 27 Energy Supply 15 Research: Publishing 27 Energy: Meters 15 Retail Trade: Coventry 28 Erasmus+ Programme and Shipping: Tees Valley 28 Horizon Europe 16 Solar power: Faversham 29 Fireworks: Safety 16 Unemployment: Coronavirus 29 Green Homes Grant Scheme 17 Weddings: Coronavirus 30 Horizon Europe 18 Wind Power 31 Housing: Energy 19 Hydrogen 20 CABINET OFFICE 31 Musicians: Coronavirus 44 Ballot Papers: Visual Skateboarding: Coronavirus 44 Impairment 31 -

Redalyc.TRENDS in RESEARCH on TERRESTRIAL SPECIES of THE

Mastozoología Neotropical ISSN: 0327-9383 [email protected] Sociedad Argentina para el Estudio de los Mamíferos Argentina Pérez-Irineo, Gabriela; Santos-Moreno, Antonio TRENDS IN RESEARCH ON TERRESTRIAL SPECIES OF THE ORDER CARNIVORA Mastozoología Neotropical, vol. 20, núm. 1, 2013, pp. 113-121 Sociedad Argentina para el Estudio de los Mamíferos Tucumán, Argentina Available in: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=45728549008 How to cite Complete issue Scientific Information System More information about this article Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America, the Caribbean, Spain and Portugal Journal's homepage in redalyc.org Non-profit academic project, developed under the open access initiative Mastozoología Neotropical, 20(1):113-121, Mendoza, 2013 Copyright ©SAREM, 2013 Versión impresa ISSN 0327-9383 http://www.sarem.org.ar Versión on-line ISSN 1666-0536 Artículo TRENDS IN RESEARCH ON TERRESTRIAL SPECIES OF THE ORDER CARNIVORA Gabriela Pérez-Irineo and Antonio Santos-Moreno Laboratorio de Ecología Animal, Centro Interdisciplinario de Investigación para el Desarrollo Integral Regional, Unidad Oaxaca, Instituto Politécnico Nacional, Hornos 1003, 71230 Santa Cruz Xoxocotlán, Oaxaca, México [Correspondence: Gabriela Pérez Irineo <[email protected]>]. ABSTRACT. Information regarding trends in research on terrestrial species of the order Carnivora can provide an understanding of the degree of knowledge of the order, or lack thereof, as well as help identifying areas on which to focus future research efforts. With the aim of providing information on these trends, this work presents a review of the thematic focuses of studies addressing this order published over the past three de- cades. Relevant works published in 16 scientific journals were analyzed globally and by continent with respect of topics, species, and families. -

Visitor Attraction Trends England 2003 Presents the Findings of the Survey of Visits to Visitor Attractions Undertaken in England by Visitbritain

Visitor Attraction Trends England 2003 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS VisitBritain would like to thank all representatives and operators in the attraction sector who provided information for the national survey on which this report is based. No part of this publication may be reproduced for commercial purp oses without previous written consent of VisitBritain. Extracts may be quoted if the source is acknowledged. Statistics in this report are given in good faith on the basis of information provided by proprietors of attractions. VisitBritain regrets it can not guarantee the accuracy of the information contained in this report nor accept responsibility for error or misrepresentation. Published by VisitBritain (incorporated under the 1969 Development of Tourism Act as the British Tourist Authority) © 2004 Bri tish Tourist Authority (trading as VisitBritain) Cover images © www.britainonview.com From left to right: Alnwick Castle, Legoland Windsor, Kent and East Sussex Railway, Royal Academy of Arts, Penshurst Place VisitBritain is grateful to English Heritage and the MLA for their financial support for the 2003 survey. ISBN 0 7095 8022 3 September 2004 VISITOR ATTR ACTION TRENDS ENGLAND 2003 2 CONTENTS CONTENTS A KEY FINDINGS 4 1 INTRODUCTION AND BACKGROUND 12 1.1 Research objectives 12 1.2 Survey method 13 1.3 Population, sample and response rate 13 1.4 Guide to the tables 15 2 ENGLAND VISIT TRENDS 2002 -2003 17 2.1 England visit trends 2002 -2003 by attraction category 17 2.2 England visit trends 2002 -2003 by admission type 18 2.3 England visit trends -

University of Florida Thesis Or Dissertation Formatting

UNDERSTANDING CARNIVORAN ECOMORPHOLOGY THROUGH DEEP TIME, WITH A CASE STUDY DURING THE CAT-GAP OF FLORIDA By SHARON ELIZABETH HOLTE A DISSERTATION PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 2018 © 2018 Sharon Elizabeth Holte To Dr. Larry, thank you ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to thank my family for encouraging me to pursue my interests. They have always believed in me and never doubted that I would reach my goals. I am eternally grateful to my mentors, Dr. Jim Mead and the late Dr. Larry Agenbroad, who have shaped me as a paleontologist and have provided me to the strength and knowledge to continue to grow as a scientist. I would like to thank my colleagues from the Florida Museum of Natural History who provided insight and open discussion on my research. In particular, I would like to thank Dr. Aldo Rincon for his help in researching procyonids. I am so grateful to Dr. Anne-Claire Fabre; without her understanding of R and knowledge of 3D morphometrics this project would have been an immense struggle. I would also to thank Rachel Short for the late-night work sessions and discussions. I am extremely grateful to my advisor Dr. David Steadman for his comments, feedback, and guidance through my time here at the University of Florida. I also thank my committee, Dr. Bruce MacFadden, Dr. Jon Bloch, Dr. Elizabeth Screaton, for their feedback and encouragement. I am grateful to the geosciences department at East Tennessee State University, the American Museum of Natural History, and the Museum of Comparative Zoology at Harvard for the loans of specimens.