Circular Dormitories Between City and Private Life

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Udviklingsplan Udviklingsplan

Finansministeriet Finansministeriet UDVIKLINGSPLAN Slots- og Ejendomsstyrelsen Løngangstræde 21 1468 København K Tlf.: 33 92 63 00 Slots- og Ejendomsstyrelsen har ansvaret og brugernes ønsker og behov. Til dette formål E-mail: [email protected] for nogle af de mest betydningsfulde danske udarbejder og reviderer styrelsen løbende www.ses.dk slotte, palæer og haver. Det er styrelsens opgave udviklingsplaner for slottene og haverne. at optimere samfundets nytte af disse anlæg, således at de bevares og nyttiggøres i dag En udviklingsplan må ikke forveksles med og for fremtiden. en egentlig handlingsplan. De aktiviteter, som skitseres i udviklingsplanen, bliver løbende CHRISTIANIAOMRÅDETS VOLDANLÆG Det er en grundlæggende forpligtelse, at anlæg- taget op til revision og gennemførelsen afhænger gene bevares, så kommende generationer kan af faktorer som brugerhensyn, anlæggenes opleve dem som autentiske, velbevarede anlæg aktuelle tilstand, økonomi etc. med stor kulturhistorisk fortælleværdi. Det er samtidig en forpligtelse at sikre anlæggene Udviklingsplanerne fastlægger strategier synlighed og tilgængelighed for offentligheden for havens bevaring, udvikling og nyttiggørelse og understøtte de rekreative, turistmæssige og forholder sig til og imødegår forskellige og identitetsbærende potentialer, som denne problematikker i relation hertil. På den måde del af kulturarven repræsenterer. sikres et gennemarbejdet perspektiv for den videre udvikling. Slots- og Ejendomsstyrelsen skal sikre, at statens slotte og haver fortsat udvikles under en afbalanceret afvejning af bevaringsforpligtigelsen UDVIKLINGSPLAN CHRISTIANIAOMRÅDETS VOLDANLÆG Finansministeriet SEPTEMBER 2006 UDVIKLINGSPLAN CHRISTIANIAOMRÅDETS VOLDANLÆG SEPTEMBER 2006 INDHOLD CHRISTIAniAOMRÅDETS VOLDANLÆG . 4 RELATION TIL ANDEN PLANLÆGninG . 8 HISTORIEN . 12 EN DEL AF FÆSTninGSRinGEN . 24 CHRISTIAniAOMRÅDETS VOLDANLÆG I DAG . 28 BEBYGGELSE . 30 TRÆER . 32 GRÆS OG KRAT . 34 VANDOMRÅDERNE . 36 STIER OG ADGANGSFORHOLD . 38 NATURKVALITETER . -

The Launch of the Harbour Circle, 29 May Program

PROGRAM FOR THE LAUNCH OF THE HARBOUR CIRCLE, 29 MAY 1 11:00-17:00 7 10:00 TO 17:30 COPENHAGEN BICYCLES LAUNCH OF THE HARBOUR CIRCLE – THE DANISH EXPERIENCE The official inauguration of the Harbour Circle will take place at the northern Begin your cycling experience at the Copenhagen Bicycles store, end of Havnegade from 11:00-11:30. Copenhagen Major of Technical and Environ- which offers bikes for hire. Knowledgeable guides look forward mental Affairs Morten Kabell and Director of the Danish Cyclist Federation Klaus to showing you around on bike rides along the Harbour Circle Bondam will hold speeches. Bring your bike or rent one locally and join them starting at 11:00. The store also offers support services such as when they inaugurate the Harbour Circle with a bicycle parade starting from Havnegade and continuing over the bridges of Knippelsbro, Cirkelbroen and compressed air for your bike tires and a cloth to wipe your bike Bryggebroen before returning to Havnegade via Kalvebod Brygge and Christians clean. Do like the Danes – and hop on a bike! Brygge, a route totalling 7km. Havnegade will be a celebration zone with on-stage NYHAVN 44, 1058 COPENHAGEN music and deejay entertainment in addition to bicycle concerts, bicycle stalls and www.copenhagenbicycles.dk bicycle coffee and food vendors. The event is hosted by Master Fatman on his cargo bike. Come and join the party! HAVNEGADE, 1058 KØBENHAVN K 2 11:30-16:30 BIKE PARADE 8 11:00-17:00. OPEN HOUSE AT ALONG THE HARBOUR CIRCLE FÆSTNINGENS MATERIALGÅRD/BLOX After the initial bike parade there will be regular departures of Learn more about the BLOX project – the new home of the Danish Architecture cycling teams all day from Havnegade along the new route. -

Planning and Promotion of Cycling in Denmark - Study Trip April 28-30, 2019

Planning and Promotion of Cycling in Denmark - Study Trip April 28-30, 2019 The study includes lectures about Odense, Copenhagen and Gladsaxe (a Copenhagen suburb, entitled "This Year's Bicycle Municipality" by Danish Cyclists' Federation 2016). Besides lectures there will be plenty of bicycle trips in and outside Copenhagen, some of them on bicycle super highways, others in combination with public transport, all of which will enable the participants to experience Danish cycling themselves. The study trip offers several opportunities for formal and informal discussions. Sunday, April 28, 2019 (optional) 19:30-21:00 Evening get together. Monday, April 29, 2019 08:30-10:00 Bicycle excursion in central Copenhagen, passing Dronning Louises Bro (Europe’s busiest bicycle street) and other high- level bicycle facilities, ending at Cyklistforbundet (Danish Cyclists’ Federation). 10:00-11:00 Klaus Bondam, director of Cyklistforbundet (Danish Cyclists' Federation) and former Mayor of Traffic in Copenhagen: How to campaign for cycling in a bicycle friendly environment. 11:00-12:00 Bicycle excursion to Islands Photo: Jens Erik Larsen Brygge via the iconic Cykelslangen and Bryggebroen. 12:00-13:00 Lunch 13:00-14:00 City of Copenhagen, Bicycle Program Office: Promotion of cycling in Copenhagen, current strategy and main inputs and outcomes. 14:00-14:45 Sidsel Birk Hjuler, manager of project "Supercykelstier": Cycle Superhighways in the Capital Region, challenges and results. 14:45-15:00 Coffee break 15:00-16:00 Troels Andersen, senior traffic planner from Odense Municipality: Odense City of Cyclists, planning, public relations and realization. 16:00-16:15 Jens Erik Larsen and Thomas Krag: Reflections on the day’s excursions and introduction to the last part. -

Today's Adult English Language Learner

Meeting the Language Needs of TODAY’S ADULT ENGLISH LANGUAGE LEARNER Companion Learning Resource CONTENTS INTRODUCTION About This Resource 2 How Can We Meet the Language 3 Needs of Today’s Adult ELLs? How to Navigate This Resource 4 INSTRUCTIONAL IMPLICATIONS What Is Rigorous Adult ELA 5 Instruction? What Does Rigorous Adult ELA 6 Instruction Look Like? Welcome to Meeting the Language Needs of Today’s Adult English CONCEPTS IN ACTION Engaging Learners With 7 Language Learner: Companion Learning Resource. Here you will find Academic Language Teaching Through Projects to Meet examples of approaches, strategies, and lesson ideas that will lead you 13 Rigorous Language Demands to more engaging, rigorous, and effective English language acquisition Accessing Complex Informational Texts 18 (ELA) instruction. You will also find numerous links to websites, videos, Employing Evidence in Speaking 21 audio files, and more. Each link is an invitation to explore rigorous ELA and Writing Building Content Knowledge 23 instruction more deeply, guiding you to enhanced teaching and learning! Conclusion 25 ADDITIONAL RESOURCES Companion Learning Resource A project of American Institutes for Research Resource Index 26 Acknowledgments: Author: Patsy Egan Vinogradov, ATLAS, Hamline University Reviewer: Susan Finn Miller, Lancaster Lebanon IU 13 Works Cited 27 Editors: Mariann Fedele-McLeod and Catherine Green Appendix: Permissions INTRODUCTION ABOUT THIS RESOURCE Adult English language learners (ELLs) are in transition. They are receiving adult education services in order to transition into the next phase in their lives. To do this successfully, they may need to become more comfortable and confident in navigating their communities, obtain skills to find or advance employment, This RESOURCE or perhaps earn a college degree. -

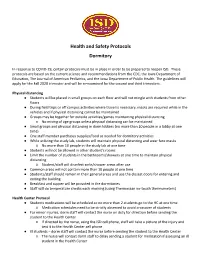

Health and Safety Protocols Dormitory

Health and Safety Protocols Dormitory In response to COVID-19, certain protocols must be in place in order to be prepared to reopen ISD. These protocols are based on the current science and recommendations from the CDC, the Iowa Department of Education, The Journal of American Pediatrics, and the Iowa Department of Public Health. The guidelines will apply for the Fall 2020 trimester and will be re-examined for the second and third trimesters. Physical distancing ● Students will be placed in small groups on each floor and will not mingle with students from other floors ● During field trips or off campus activities where travel is necessary, masks are required while in the vehicles and if physical distancing cannot be maintained * ● Groups may be together for outside activities/games maintaining physical distancing ○ No mixing of age groups unless physical distancing can be maintained ● Small groups and physical distancing in dorm lobbies (no more than 10 people in a lobby at one time) ● One staff member purchases supplies/food as needed for dormitory activities * ● While utilizing the study lab, students will maintain physical distancing and wear face masks ○ No more than 10 people in the study lab at one time ● Students will not be allowed in other student’s rooms ● Limit the number of students in the bathrooms/showers at one time to maintain physical distancing ○ Student/staff will disinfect sinks/shower areas after use ● Common areas will not contain more than 10 people at one time ● Students/staff should remain in their general areas -

Velkommen Til Københavns Havn

Fyr: Ind- og udsejling til/fra Miljøstation Jernbanebroen Teglværksbroen Alfred Nobels Bro Langebro Bryghusbroen Frederiksholms Kanal/ Sdr. Frihavn Lystbådehavn Frihøjde 3 m. Frihøjde 3 m. Frihøjde 3 m. Frihøjde 7 m. Frihøjde 2 m. Slotsholms kanal er ikke tilladt, når NORDHAVNEN Sejlvidde 17 m. Sejlvidde 15 m. Sejlvidde 15 m. Sejlvidde 35 m. Sejlvidde 9,4 m. besejles fra syd de to røde signalfyr blinker Knippelsbro Ind- og udsejling til Indsejlingsrute J Frihøjde 5,4 m. Langelinie havnen til Sdr. Frihavn Sejlvidde 35 m. vinkelret på havnen FREDERIKSKA Lystbåde skal sejle Amerika Plads HAVNEHOLMEN øst for gule bøjer ENGHAVEBRYGGE Chr. IV’s Bro Nyhavnsbroen en TEGLHOLMEN Midtermol SLUSEHOLMEN Frihøjde 2,3 m. Frihøjde 1,8 m. Langelinie KALVEBOD BRYGGE Sejlvidde 9,1KASTELLET m. SLOTSHOLMEN ederiksholms Kanal r F AMAGER FÆLLED Amaliehaven Nyhavn NORDRE TOLDBOD ISLANDS BRYGGE Chris tianshavns Kanal kanal retning Sjællandsbroen Slusen Lille Langebro DOKØEN Indsejling forbeholdt Frihøjde 3 m. Max. bredde 10,8 m. Frihøjde 5,4 m. NYHOLM Sejlvidde 16 m. Max. længde 53 m. Sejlvidde 35 m. CHRISTIANSHAVN REFSHALEØEN erhvervsskibe HOLMEN (NB Broerne syd Herfra og sydpå: for Slusen max. 3 m. Bryggebroen ARSENALØEN Ikke sejlads for sejl i højden). Se slusens Den faste sektion åbningstider på byoghavn. Frihøjde 5,4 m. dk/havnen/sejlads-og-mo- Sejlvidde 19 m. Cirkelbroen Trangravsbroen Al sejlads med lystbåde torbaade/ Svingbroen Frihøjde 2,25 m. Frihøjde 2,3 m. gennem Lynetteløbet Sejlvidde 34 m. Sejlvidde 9 m. Sejlvidde 15 m. Christianshavns Kanal Inderhavnsbroen sejles nord - syd Frihøjde 5,4 m. Sejlvidde 35 m. PRØVESTENEN Lavvande ØSTHAVNEN VELKOMMEN TIL Erhvervshavn – al sejlads er forbeholdt KØBENHAVNS HAVN erhverstrafikken Velkommen til hovedstadens smukke havn. -

DAILY Commoiwealth, MANSION HOUSE, W EI SI U Ell HOUSE

his country, in the battles of Palo Alto, Reseca de Leave was granted to bring in the following bills: Also a bill to amend an act entitled, an act to THE DAILY COMMONWEALTH. la Palma.and Monterey, and in his last and unparal- To Mr. GARNETT a bill for the benefit of the construct a road from Rochester to Russeilville; re- Frankfort Advertisements. leled achievement at Buena Vista their admiration heirs of J. II. Andersen, deceased; referred. ferred. of his virtues, his modesty, his justice, his kindness To Mr. ASKINS a bill to revise and amend the To Mr. HUGHES a bill for the benefit of FRANKFORT.. WEDNESDAY, JAN. 5, 1843. and benevolence to the soldiers under his command, charter of Augusta, CytithJana and Georgetown Clerks in Union Circuit and County Courts; re- FRANKFORT SHOE STORE, and that, if possible, more elevated and manly spir- Turnpike road; referred. ferred. (Sign of the Hig lloot.) KENTUCKY LEGISLATURE. it of moderation and magnanimity, which he has Also a bill to provide for running a line between Mr. HUGHES offered the following: uniformly displayed towards the defeated and pros- the counties of 31cCracken and Pendleton; referred. Resolved, That the committee on the Judiciary be subscriber would respectfully tall the attention r.f his THE curtomers and visiters generally, to Lis large stock of foes hereby tender to him the McAd-amiz- instructed to inquire as to the propriety of publishing IN SENATE. trate of his country To Mr. TALBUTT a bill to grade and e of Kentucky There- all local laws, &.C.; lost. -

W E've a Story to T Ell December 16, 2018

N N I V E R S h A A t A IN R A Child’s View of the Living Nativity N T BR 5 U O Y O 7 O The Living Nativity has been a ministry of our church for over 50 years. My family moved K . M to Birmingham in 1970 and I can remember participating when I was a child. Back then, the manger was on the driveway coming down from the preschool education porte cochere. Gabriel and the multitude of angels appeared on the roof of the porte cochere. To get to the roof, the 1944 2019 angels were told to hold the bottom of their white robe in their mouth and climb an old ladder. B Years later, the old ladder was replaced by steps on some scaffolding. You had to watch those A H angels. If you turned your back, they would start throwing rocks off the roof at the shepherds P C T U R down below. I S T C H When my son was four, someone asked him what he wanted to be in the Living Nativity. He carefully thought for a minute and announced he wanted to be one of the sheep. For the 50th anniversary of the show, we had angels ranging from 2 to 92. What an exciting time to see so many generations coming together, listening to Dr. Nelson’s voice telling the story of the birth of Christ. One of the families living near the church has a special needs N I V E R child. -

How Educators Can Advocate for English Language Learners

How Educators Can Advocate for English Language Learners ALL IN! TABLE OF CONTENTS LISTEN UP! ...................................................................................................................4 WHY ADVOCATE FOR ENGLISH LANGUAGE LEARNERS? ...............................6 Underserved and Underrepresented .................................................................7 All Advocacy Is Local .............................................................................................8 Demographics Are Destiny ..................................................................................9 ADVOCACY IN ACTION ......................................................................................... 10 Five Steps to ELL Advocacy ................................................................................11 Web Resources ....................................................................................................13 Additional Rtng ....................................................................................................13 CURRICULUM ACCESS AND LANGUAGE RIGHTS............................................ 15 Ensuring Equal Access ........................................................................................15 Valuing Home Languages ..................................................................................16 Advocacy Strategies ............................................................................................16 Scenario 1 .............................................................................................................17 -

National Register of Historic Places Registration Form

NPS Form 10-900 OMB No. 1024-0018 United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form This form is for use in nominating or requesting determinations for individual properties and districts. See instructions in National Register Bulletin, How to Complete the National Register of Historic Places Registration Form. If any item does not apply to the property being documented, enter "N/A" for "not applicable." For functions, architectural classification, materials, and areas of significance, enter only categories and subcategories from the instructions. 1. Name of Property Historic name: _Cedar Hill _________________________________________________ Other names/site number: Reed, Mrs. Elizabeth I.S., Estate;_________________________ “Clouds Hill Victorian House Museum”____________________ Name of related multiple property listing: ____N/A_______________________________ (Enter "N/A" if property is not part of a multiple property listing _____ _______________________________________________________________________ 2. Location Street & number: __4157 Post Road___________________________________________ City or town: _Warwick____ State: __RI_ Zip Code: __ 02818___County: _Kent______ Not For Publication: Vicinity: ____________________________________________________________________________ 3. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act, as amended, I hereby certify that this x nomination ___ request for determination -

Copenhagen Canals

MIN. MINUTES TO THE GOBOAT BASE MIN. Approximately the time it takes to sail straight back to GoBoat. COPENHAGEN 30 MIN TO BASE NO STOPPING It is prohibited to stop in areas marked CANALS MIN. with this sign out of respect for our MIN. neighbours. SERVICE NO: +45 40 26 14 64 MIN. RED MARKING It is prohibited to sail in areas marked with red because of shallow water and known to be a restricted area. KYSSETRAPPEN SHALLOW WATER! INDERHAVNSBROEN The yellow buoys indicate shallow water. Please keep a distance! QUIET ZONE S KAYAKBAR We kindly ask you to keep the noise STREET FOOD MARKET level to a minimum in the quiet zone. ONE WAY TRAFFIC KNIBBELSBRO 40 MIN TO BASE The arrows mark the direction of the CHRISTIANSHAVN BÅDUDLEJ. trafficinthecanals.Itisprohibitedand dangerous to sail in the direction against thetraffic. LANGEBRO TRAFFIC LIGHT Do not sail through the canal when faced with a red light. Position the boat at the side of the canal and wait for yellow light. GREEN ISLAND ISLANDS BRYGGE MIN. ISLANDS BRYGGE KULTURHUS FISKETORVET BRYGGEBROEN BLOX Culture center - a magnet for urban life, architecture, design and new ideas . 30 MIN TO BASE AMALIENBORG Amalienborg is the main residence of the Danish Royal Family. TEGLVÆRKET Oasis in the sourthern part of the MIN. harbour with beach, bar, music and MOORING PICNICMIN.TOILET foodmarket. MIN.MIN. MIN. THE OPERA 1 HOUR TO BASE The national opera house of Denmark. MIN. AALBORG MIN. UNIVERSITET MOORING CHRISTIANIA Mooring spaces where you are Freetown & autonomous neighbourhood TV2 MIN. allowed to dock. -

Dormitory Norms

DORMITORY NORMS V:11.18.18SS OBJECTIVE OF SYRACUSE UNIVERSITY: A primary objective of the Syracuse Madrid dormitory program is to integrate students into Spanish society. Through this experience, students will have the opportunity to engage with Spanish students and improve their Spanish language skills while learning about Spain and experiencing Spanish culture. The residence hall, Colegio Mayor El Faro, inaugurated in September 2016 is a luxury student housing facility in the heart of Madrid, situated in the Moncloa neighborhood of downtown Madrid and is a 25-minute walk or a quick commute to the Syracuse Madrid Center. The rooms are furnished, including a safety deposit box, a small kitchenette with a sink, mini-fridge, and microwave. Bed linens and bath towels are provided and laundered weekly by the cleaning staff. Three daily meals in the El Faro cafeteria are included in this option. 1. INTRODUCTION • Syracuse Madrid students make up a small portion of those who live in the building. Other residents include Spanish and international students enrolled at local universities or in other study abroad programs. • Prior to arrival, students will have the opportunity to state their housing preferences and/or special needs. At this time, a specific roommate or random roommate may also be requested. • Syracuse Madrid prohibits discrimination based on gender, race, sexual orientation, gender identity and expression, politics and/or religion. • Students will be provided with breakfast, lunch and dinner during established and published times. Students who attend UAM or the IE in Spain may pay an increased program fee to cover additional room and board costs, where applicable.