Benwell's Lost Coal Mines a Walking Trail Sketch Plan: St

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2019 LS Polling Stations and Constituencies.Xlsx

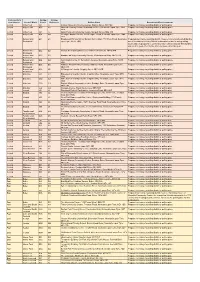

Parliamentary Polling Polling Constituency Council Ward District Reference Polling Place Returning Officer Comments Central Arthur's Hill A01 A1 Stanton Street Community Lounge, Stanton Street, NE4 5LH Propose no change to polling district or polling place Central Arthur's Hill A02 A2 Moorside Primary School, Beaconsfield Street, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE4 Propose no change to polling district or polling place 5AW Central Arthur's Hill A03 A3 Spital Tongues Community Centre, Morpeth Street, NE2 4AS Propose no change to polling district or polling place Central Arthur's Hill A04 A4 Westgate Baptist Church, 366 Westgate Road, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE4 Propose no change to polling district or polling place 6NX Central Benwell and B01 B1 Broadwood Primary School Denton Burn Library, 713 West Road, Newcastle Proposed no change to polling district, however it is recommended that the Scotswood upon Tyne, NE15 7QQ use of Broadwood Primary School is discontinued due to safeguarding issues and it is proposed to use Denton Burn Library instead. This building was used to good effect for the PCC elections earlier this year. Central Benwell and B02 B2 Denton Burn Methodist Church, 615-621 West Road, NE15 7ER Propose no change to polling district or polling place Scotswood Central Benwell and B03 B3 Broadmead Way Community Church, 90 Broadmead Way, NE15 6TS Propose no change to polling district or polling place Scotswood Central Benwell and B04 B4 Sunnybank Centre, 14 Sunnybank Avenue, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE15 Propose no change to polling district or -

Geological Notes and Local Details for 1:Loooo Sheets NZ26NW, NE, SW and SE Newcastle Upon Tyne and Gateshead

Natural Environment Research Council INSTITUTE OF GEOLOGICAL SCIENCES Geological Survey of England and Wales Geological notes and local details for 1:lOOOO sheets NZ26NW, NE, SW and SE Newcastle upon Tyne and Gateshead Part of 1:50000 sheets 14 (Morpeth), 15 (Tynemouth), 20 (Newcastle upon Tyne) and 21 (Sunderland) G. Richardson with contributions by D. A. C. Mills Bibliogrcphic reference Richardson, G. 1983. Geological notes and local details for 1 : 10000 sheets NZ26NW, NE, SW and SE (Newcastle upon Tyne and Gateshead) (Keyworth: Institute of Geological Sciences .) Author G. Richardson Institute of Geological Sciences W indsorTerrace, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE2 4HE Production of this report was supported by theDepartment ofthe Environment The views expressed in this reportare not necessarily those of theDepartment of theEnvironment - 0 Crown copyright 1983 KEYWORTHINSTITUTE OF GEOLOGICALSCIENCES 1983 PREFACE "his account describes the geology of l:25 000 sheet NZ 26 which spans the adjoining corners of l:5O 000 geological sheets 14 (Morpeth), 15 (Tynemouth), 20 (Newcastle upon Tyne) and sheet 22 (Sunderland). The area was first surveyed at a scale of six inches to one mile by H H Howell and W To~ley. Themaps were published in the old 'county' series during the years 1867 to 1871. During the first quarter of this century parts of the area were revised but no maps were published. In the early nineteen twenties part of the southern area was revised by rcJ Anderson and published in 1927 on the six-inch 'County' edition of Durham 6 NE. In the mid nineteen thirties G Burnett revised a small part of the north of the area and this revision was published in 1953 on Northumberland New 'County' six-inch maps 85 SW and 85 SE. -

Know Your Councillors 2019 — 2020

Know Your Councillors 2019 — 2020 Arthur’s Hill Benwell & Scotswood Blakelaw Byker Callerton & Throckley Castle Chapel Dene & South Gosforth Denton & Westerhope Ali Avaei Lord Beecham DCL DL Oskar Avery George Allison Ian Donaldson Sandra Davison Henry Gallagher Nick Forbes C/o Members Services Simon Barnes 39 The Drive C/o Members Services 113 Allendale Road Clovelly, Walbottle Road 11 Kelso Close 868 Shields Road c/o Leaders Office Newcastle upon Tyne C/o Members Services Newcastle upon Tyne Newcastle upon Tyne Newcastle upon Tyne Walbottle Chapel Park Newcastle upon Tyne Newcastle upon Tyne NE1 8QH Newcastle upon Tyne NE3 4AJ NE1 8QH NE6 2SY Newcastle upon Tyne Newcastle upon Tyne NE6 4QP NE1 8QH 0191 274 0627 NE1 8QH 0191 285 1888 07554 431 867 0191 265 8995 NE15 8HY NE5 1TR 0191 276 0819 0191 211 5151 07765 256 319 07535 291 334 07768 868 530 Labour Labour 07702 387 259 07946 236 314 07947 655 396 Labour Liberal Democrat Labour Labour Newcastle First Independent Liberal Democrat [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Marc Donnelly Veronica Dunn Melissa Davis Joanne Kingsland Rob Higgins Nora Casey Stephen Fairlie Aidan King 17 Ladybank Karen Robinson 18 Merchants Wharf 78a Wheatfield Road 34 Valley View 11 Highwood Road C/o Members Services 24 Hawthorn Street 15 Hazelwood Road Newcastle upon Tyne 441 -

The London Gazette, November 20, 1860

4344 THE LONDON GAZETTE, NOVEMBER 20, 1860. relates to each of the parishes in or through which the Ecclesiastical Commissioners for England, and the said intended railway and works will be made, in the occupation of the lessees of Tyne Main together with a copy of the said Gazette Notice, Colliery, with an outfall or offtake drift or water- will be deposired for public inspection with the course, extending from the said station to a p >int parish clerk of each such parish at his residence : immediately eastward of the said station ; on a and in the case of any extra-parochial place with rivulet or brook, in the chapelry of Heworth, in the parish clerk of some parish immediately ad- the parish of Jarrow, and which flows into the joining thereto. river Tyne, in the parish of St Nicholas aforesaid. Printed copies of the said intended Bill will, on A Pumping Station, with shafts, engines, and or before the 23rd day of December next, be de- other works, at or near a place called the B Pit, posited in the Private Bill Office of the House of at Hebburn Colliery, in the township of Helburn, Commons. in the parish of Jarrow, on land belonging to Dated this eighth day of November, one thou- Lieutenant-Colonel Ellison, and now in the occu- sand eight hundred and sixty. pation of the lessees of Hebburn Colliery, with an F. F. Jeyes} 22, Bedford-row, Solicitor for outfall or offtake drift or watercourse, extending the Bill. from the said station to the river Tyne aforesaid, at or near a point immediately west of the Staith, belonging to the said Hebburn Colliery. -

Northumberland and Durham Family History Society Unwanted

Northumberland and Durham Family History Society baptism birth marriage No Gsurname Gforename Bsurname Bforename dayMonth year place death No Bsurname Bforename Gsurname Gforename dayMonth year place all No surname forename dayMonth year place Marriage 933ABBOT Mary ROBINSON James 18Oct1851 Windermere Westmorland Marriage 588ABBOT William HADAWAY Ann 25 Jul1869 Tynemouth Marriage 935ABBOTT Edwin NESS Sarah Jane 20 Jul1882 Wallsend Parrish Church Northumbrland Marriage1561ABBS Maria FORDER James 21May1861 Brooke, Norfolk Marriage 1442 ABELL Thirza GUTTERIDGE Amos 3 Aug 1874 Eston Yorks Death 229 ADAM Ellen 9 Feb 1967 Newcastle upon Tyne Death 406 ADAMS Matilda 11 Oct 1931 Lanchester Co Durham Marriage 2326ADAMS Sarah Elizabeth SOMERSET Ernest Edward 26 Dec 1901 Heaton, Newcastle upon Tyne Marriage1768ADAMS Thomas BORTON Mary 16Oct1849 Coughton Northampton Death 1556 ADAMS Thomas 15 Jan 1908 Brackley, Norhants,Oxford Bucks Birth 3605 ADAMS Sarah Elizabeth 18 May 1876 Stockton Co Durham Marriage 568 ADAMSON Annabell HADAWAY Thomas William 30 Sep 1885 Tynemouth Death 1999 ADAMSON Bryan 13 Aug 1972 Newcastle upon Tyne Birth 835 ADAMSON Constance 18 Oct 1850 Tynemouth Birth 3289ADAMSON Emma Jane 19Jun 1867Hamsterley Co Durham Marriage 556 ADAMSON James Frederick TATE Annabell 6 Oct 1861 Tynemouth Marriage1292ADAMSON Jane HARTBURN John 2Sep1839 Stockton & Sedgefield Co Durham Birth 3654 ADAMSON Julie Kristina 16 Dec 1971 Tynemouth, Northumberland Marriage 2357ADAMSON June PORTER William Sidney 1May 1980 North Tyneside East Death 747 ADAMSON -

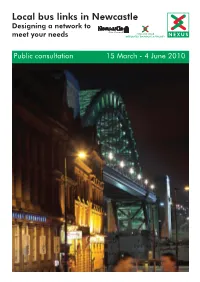

Local Bus Links in Newcastle Designing a Network To

Local bus links in Newcastle Designing a network to TYNE AND WEAR meet your needs INTEGRATED TRANSPORT AUTHORITY Public consultation 15 March - 4 June 2010 Local bus links in Newcastle Designing a network to meet your needs Public consultation People in Newcastle make 47 million bus journeys annually - that’s an average of more than 173 journeys a year for every resident! Nexus, Newcastle City Council and the Tyne and Wear Integrated Transport Authority (ITA) want to make sure the network of bus services in the area meets residents’ needs. To do this, Nexus has worked together with bus companies and local councils to examine how current services operate and to look at what improvements could be made to the ‘subsidised’ services in the network, which are the ones Nexus pays for. We have called this the Accessible Bus Network Design Project (see below). We want your views on the proposals we are now making to improve bus services in Newcastle, which you can find in this document. We want to hear from you whether you rely on the bus in your daily life, use buses only occasionally or even if you don’t – but might consider doing so in the future. You’ll find details of different ways to respond on the back page of this brochure. This consultation forms part of the Tyne and Wear Integrated Transport Authority’s Bus Strategy, a three year action plan to improve all aspects of the bus services in Tyne and Wear. Copies of the Bus Strategy can be downloaded from www.nexus.org.uk/busstrategy. -

Benwell Forty Years On

Benwell forty years on: Policy and change after the Community Development Project REPORT Fred Robinson and Alan Townsend 1 Published by: Centre for Social Justice and Community Action, Durham University, UK, 2016 [email protected] www.durham.ac.uk/socialjustice This account was prepared by Fred Robinson and Alan Townsend for Imagine North East, part of the Economic and Social Research Council funded project, Imagine – connecting communities through research (grant no. ES/K002686/2). Imagine North East explored aspects of civic participation in the former Community Development Project areas in Benwell (Newcastle) and North Shields. The views expressed are those of the authors. Further reports and other materials can be found at: https://www.dur.ac.uk/socialjustice/imagine/ About the authors: Fred Robinson is a Professorial Fellow, St Chad’s College, Durham University. He has undertaken extensive research on social and economic change in the North East and the impacts of public policy. Alan Townsend is Emeritus Professor of Geography, Durham University. His interests include planning, regional development and the geography of employment and unemployment. Acknowledgements: We are very grateful to the past and current policymakers interviewed for the research on which this report is based We would also like to thank Judith Green who commented on draft material, Dave Byrne for his earlier Census analyses, and Andrea Armstrong and Sarah Banks for editorial work. Contents Introduction 3 Policy 4 The aftermath of CDP: Inner city policy 4 Property-led regeneration 5 Involving the local community in regeneration partnerships: City Challenge 6 Single Regeneration Budget programmes 8 ‘Going for Growth’ 9 A new start? 11 Conclusion 13 Statistical section: Census indicators tracking change, 1971 to 2011 15 References 17 Timeline: Benwell and Newcastle upon Tyne Policies and Politics 19 Cover photo: West End Health Resource Centre, Benwell. -

S104 Bus Time Schedule & Line Route

S104 bus time schedule & line map S104 Arthur's Hill - Scotswood View In Website Mode The S104 bus line Arthur's Hill - Scotswood has one route. For regular weekdays, their operation hours are: (1) Scotswood: 7:45 AM Use the Moovit App to ƒnd the closest S104 bus station near you and ƒnd out when is the next S104 bus arriving. Direction: Scotswood S104 bus Time Schedule 23 stops Scotswood Route Timetable: VIEW LINE SCHEDULE Sunday Not Operational Monday 7:45 AM Stanhope Street-Social Club, Arthur's Hill Avolon Place, Newcastle Upon Tyne Tuesday 7:45 AM Stanhope Street-Avison Street, Arthur's Hill Wednesday 7:45 AM Avison Place, Newcastle Upon Tyne Thursday 7:45 AM Stanhope Street-Baxterwood Court, Arthur's Hill Friday 7:45 AM Frosterley Place, Newcastle Upon Tyne Saturday Not Operational Stanhope Street-Stanton Street, Arthur's Hill Stanhope Street-Brighton Grove, Arthur's Hill 17 Brighton Grove, Newcastle Upon Tyne S104 bus Info Arthur's Hill-Brighton Grove, Arthur's Hill Direction: Scotswood 7 Westgate Road, Newcastle Upon Tyne Stops: 23 Trip Duration: 30 min Newcastle C.A.V Campus, Fenham Line Summary: Stanhope Street-Social Club, Arthur's Hill, Stanhope Street-Avison Street, Arthur's Hill, Newcastle C.A.V Campus, Fenham Stanhope Street-Baxterwood Court, Arthur's Hill, Stanhope Street-Stanton Street, Arthur's Hill, West Road-The Plaza, Fenham Stanhope Street-Brighton Grove, Arthur's Hill, Arthur's Hill-Brighton Grove, Arthur's Hill, Newcastle West Road-Colston Street, Fenham C.A.V Campus, Fenham, Newcastle C.A.V Campus, Fenham, West -

Through the Years

Benwell through the years In Maps and Pictures St James’ Heritage & Environment Group in partnership with West Newcastle Picture History Collection This book is the result of a joint project between St James’ Heritage & Environment Group and West Newcastle Picture History Collection. It is based on an exhibition of maps and photographs displayed at St James’ Church and Heritage Centre in Benwell during 2015. All the photographs come from West Newcastle Picture History Collection’s unique archive of over 19,000 photographs of West Newcastle from the 1880s to date. The Ordnance Survey maps are reproduced by kind permission of the copyright holders. Acknowledgements St James’ Heritage & Environment Group and West Newcastle Picture History Collection are both wholly volunteer-run organisations. This book would not have been possible without the work of the many volunteers, past and present, who have collected photographs, carried out research on the history of this area, planned and curated exhibitions, and encouraged so many others to explore and enjoy the history of West Newcastle. We are grateful for the support of Make Your Mark who funded the production of this book and the Imagine North East project managed by Durham University and funded by the Economic and Social Research Council through the Connected Communities programme whose financial and other support made the original exhibition possible. ©St James’ Heritage & Environment Group and West Newcastle Picture History Collection, 2015 ISBN 978-0-992183-2-3 Published by St James’ Heritage & Environment Group, 2015 Series Editor: Judith Green All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored or introduced in any form without the prior permission of the publishers. -

Northumbria PCC Property Assets List December 2015

Asset List – Police and Crime Commissioner for Northumbria Status Address Line 1 Address Line 2 Address Line 3 Address Line 4 Address Line 5 Postcode Freehold Gillbridge Police Station Livingstone Road Sunderland Tyne & Wear SR1 3AW Leasehold Sunderland Central Police Sunderland Central Railway Row Sunderland Tyne & Wear SR1 3HE Office Community Fire Station Leasehold Proposed Sunderland Unit 7, Signal House Waterloo Place Sunderland Tyne & Wear SR1 3HT Central Neighbourhood Public Enquiry Office - Not yet open to the public Freehold Former Farringdon Hall Primate Road Sunderland Tyne & Wear SR3 1TQ Police Station – For Sale Leasehold Farringdon Neighbourhood Farringdon Community North Moor Road Sunderland Tyne & Wear SR3 1TJ Police Office Fire Station Freehold Southwick Police Station Church Bank Southwick Sunderland Tyne & Wear SR5 2DU Freehold Washington Police Station The Galleries Washington Tyne & Wear NE38 7RY Freehold Houghton Police Station Dairy Lane Houghton le Spring Sunderland Tyne & Wear DH4 5BH Freehold South Shields Police Station Millbank South Shields Tyne & Wear NE33 1RR Freehold Boldon Police Station North Road Boldon Colliery Tyne & Wear NE35 9AF Freehold Harton Police Station 187 Sunderland Road Harton South Shields Tyne & Wear NE34 6AQ Freehold Former Hebburn Police Victoria Road East Hebburn Tyne & Wear NE31 1XF Station – For Sale Leasehold Hebburn Police Office Hebburn Community Victoria Road Hebburn Tyne & Wear NE31 1UD Fire Station Leasehold Hebburn Neighbourhood Hebburn Central Rose Street Hebburn Tyne and -

Roman Catholic Registers

TYNE & WEAR ARCHIVES USER GUIDE 12 REGISTERS OF THE ROMAN CATHOLIC CHURCH This User Guide gives details of the registers held at this office for Catholic Parishes in Tyne and Wear, and microfilm copies available for some parishes outside Tyne and Wear. x = Baptisms m = marriages d = deaths Most of the registers listed below are now on microfilm and a reader should be booked in advance if you wish to consult these records. Please enquire in advance about access to any unlisted collections. REGISTERS FOR PARISHES IN TYNE & WEAR Annitsford, St John (MF 2047) x 1863-1919 m 1873-99 d 1863-1937 Backworth, Our Lady and St Edmund's (C.BA1) x 1901-55 m 1901-27 d 1901-21 Bells Close, St George (C.LM1) x 1869-1925 m 1872-1934 d 1884-85, 1903-30 Benton, St Aidan (C.LO7) x 1900-62 m 1911-57 d 1912-52 Benwell, St Joseph (C.NC103) x 1903-47 m 1904-75 d 1903-67 1 Birtley, St Joseph's (C.BI3) x 1745-1953 m 1846-1955 d 1856-1959 (includes x m b transcripts 1916-19 for Belgian Refugee Community at Elisabethville, Birtley) Blaydon, St Joseph's (C.BL4) x 1898-1936 m 1899-1921 d 1904-92 Byermoor, Sacred Heart (C.WH1) x 1869-1937 m 1873-1910 d 1873-1927 Byker, St Lawrence (C.NC63) x 1907-53 m 1907-47, 1974-89 d 1907-68 Chopwell, Our Lady of Lourdes with Sacred Heart, Low Westwood (C.WI12) x 1899-1945 m 1903-58 d 1904-85 Crawcrook, St Agnes (C.CK1) x 1892-1953, 1962-73 m 1894-1956, 1988-92 d 1902-57 Dunston, St Philip Neri (C.GA24) x 1882-1949 m 1884-1905, 1908-35 d 1882-96, 1902-54 Easington Lane, St Mary (C.EL4) x 1925-72 Elswick, St Michael See Newcastle, -

Buddle Collection Vols 20 24

Reference Code: NRO 3410 Papers of the North of England Institute of Mining and Mechanical Engineers NRO 3410/Bud Buddle Collection Creator(s): Buddle, John, d 1843, colliery viewer Buddle, John, d 1806, colliery viewer Immediate Source of Acquisition The papers were presented to the Mining Institute by Buddle Atkinson, a descendant of John Buddle's nephew, in various installments. Scope and Content The Buddle Collection comprises the working papers of John Buddle, d.1843; with some papers of his father, also John, d. 1806 and papers of other viewers collected by the Buddles in the course of their work The major part of the collection is a series of report and memoranda books compiled by John Buddle junior together with colliery journals and diaries of work. The collection also contains colliery notebooks of John Buddle senior, a series of lining books, personal papers and a collection of bound volumes of the papers of Thomas Young Hall, mining engineer, also collected by the Buddle Atkinson family NRO 3410/Bud/1-31 Colliery Memoranda of John Buddle. Extent and Form: 31 VOLUMES Physical characteristics: Half bound leather entitled Colliery Memoranda and labelled with volume number on spine, vols 1 - 28 approx 37cm x 26cm and vols 29 - 31 approx 26cm x 20cm, coat of arms of the Buddle Atkinson family inside front cover of each volume Scope and Content 31 volumes containing reports, correspondence, accounts and borings of John Buddle, senior and junior Arrangement Original numbered series, Reference: NRO 3410/Bud/20 Colliery Memoranda Creation dates: 1786 - 1838 Extent and Form: 105pp.