WIM BLOCKMANS Rulers Ihroughout the Ages Have Feit the Need to Have

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download Thesis

MASTERARBEIT ANALYSING THE POTENTIAL OF NETWORK KERNEL DENSITY ESTIMATION FOR THE STUDY OF TOURISM BASED ON GEOSOCIAL MEDIA DATA Ausgeführt am Department für Geodäsie und Geoinformation der Technischen Universität Wien unter der Anleitung von Francisco Porras Bernárdez, M.Sc., TU Wien und Prof. Dr. Nico Van de Weghe, Universität Gent (Belgien) Univ.Prof. Mag.rer.nat. Dr.rer.nat. Georg Gartner, TU Wien durch Marko Tošić Laaer-Berg-Straße 47B/1028B, 1100 Wien 10.09.2019 Unterschrift (Student) MASTER’S THESIS ANALYSING THE POTENTIAL OF NETWORK KERNEL DENSITY ESTIMATION FOR THE STUDY OF TOURISM BASED ON GEOSOCIAL MEDIA DATA Conducted at the Department of Geodesy and Geoinformation Vienna University of Technology Under the supervision of Francisco Porras Bernárdez, M.Sc., TU Wien and Prof. Dr. Nico Van de Weghe, Ghent University (Belgium) Univ.Prof. Mag.rer.nat. Dr.rer.nat. Georg Gartner, TU Wien by Marko Tošić Laaer-Berg-Straße 47B/1028B, 1100 Vienna 10.09.2019 Signature (Student) ACKNOWLEDGMENTS If someone told me two years ago that I will sit now in a computer room of the Cartography Research Group at TU Wien, writing Acknowledgments of my finished master’s thesis, I would say “I don’t believe you!” This whole experience is something that I will always carry with me. Different cities, universities, people, cultures, learning and becoming proficient in a completely new field; these two years were a rollercoaster. First and foremost, I would like to thank my supervisor Francisco Porras Bernárdez, muchas gracias por tu paciencia, motivación y apoyo, por compartir tu conocimiento conmigo. Esta tesis fue posibile gracias a ti. -

Stories of the Saints

Conditions and Terms of Use PREFACE Copyright © Heritage History 2009 With the spread of Christ's teaching carried by the far- Some rights reserved travelled Apostles, the minds of men and women were touched with a great faith, their thoughts were absorbed with visions of This text was produced and distributed by Heritage History, an organization heaven and holy life on earth. Many gave up earthly desires and dedicated to the preservation of classical juvenile history books, and to the ways and devoted themselves to meditation on sacred things and promotion of the works of traditional history authors. to zealous missions and pilgrimages. In thought and feeling they The books which Heritage History republishes are in the public domain and lived in a region of their own, difficult now to conceive in its are no longer protected by the original copyright. They may therefore be reproduced perfect unworldliness. within the United States without paying a royalty to the author. Their clear belief in a heaven to which they would surely The text and pictures used to produce this version of the work, however, are pass stripped fear from their hearts, gave them a more than the property of Heritage History and are licensed to individual users with some human endurance in hardship and persecution, and an restrictions. These restrictions are imposed for the purpose of protecting the integrity unquenchable zeal in carrying their saving faith to distant lands of the work itself, for preventing plagiarism, and for helping to assure that and barbarous peoples. compromised or incomplete versions of the work are not widely disseminated. -

The Lives of the Saints

'"Ill lljl ill! i j IIKI'IIIII '".'\;\\\ ','".. I i! li! millis i '"'''lllllllllllll II Hill P II j ill liiilH. CORNELL UNIVERSITY LIBRARY Cornell University Library BR 1710.B25 1898 v.7 Lives of the saints. 3 1924 026 082 598 The original of this book is in the Cornell University Library. There are no known copyright restrictions in the United States on the use of the text. http://www.archive.org/details/cu31924026082598 *— * THE 3Utoe* of tt)e Saints; REV. S. BARING-GOULD SIXTEEN VOLUMES VOLUME THE SEVENTH *- -* . l£ . : |£ THE Itoes of tfje faints BY THE REV. S. BARING-GOULD, M.A. New Edition in 16 Volumes Revised with Introduction and Additional Lives of English Martyrs, Cornish and Welsh Saints, and a full Index to the Entire Work ILLUSTRATED BY OVER 400 ENGRAVINGS VOLUME THE SEVENTH KttljJ— PARTI LONDON JOHN C. NIMMO &° ' 1 NEW YORK : LONGMANS, GREEN, CO. MDCCCXCVIII *• — ;— * Printed by Ballantyne, Hanson & Co. At the Eallantyne Press *- -* CONTENTS' PAGE S. Athanasius, Deac. 127 SS. Aaron and Julius . I SS. AudaxandAnatholia 203 S. Adeodatus . .357 „ Agilulf . 211 SS. Alexanderandcomp. 207 S. Amalberga . , . 262 S. Bertha . 107 SS. AnatholiaandAudax 203 ,, Bonaventura 327 S. Anatolius,B. of Con- stantinople . 95 „ Anatolius, B.ofLao- dicea . 92 „ Andrew of Crete 106 S. Canute 264 Carileff. 12 „ Andrew of Rinn . 302 „ ... SS. Antiochus and SS. Castus and Secun- dinus Cyriac . 351 .... 3 Nicostra- S. Apollonius . 165 „ Claudius, SS. Apostles, The Sepa- tus, and others . 167 comp. ration of the . 347 „ Copres and 207 S. Cyndeus . 277 S. Apronia . .357 SS. Aquila and Pris- „ Cyril 205 Cyrus of Carthage . -

Royal Monastery of Brou

EN ROYAL MONASTERY The masterpiece OF BROU of an emperor’s daughter The Royal Monastery of Brou, an exceptional monument, is the result of the determination at the dawn of the Renaissance of a European Princess: Margaret of Austria (1480 – 1530), daughter of an emperor, Duchess of Savoy and Regent of the Netherlands. Its church, built to commemorate her love for her deceased husband Philibert the Handsome, is famous for its elegant tombs carved in marble and alabaster. The unity of its construction, its lavish decoration and its polychrome, glazed tiles make it a masterpiece of the Flamboyant Gothic style. The three two-storey cloisters, which reveal both the skill of the builders and the life of the monks, contain the Princess’s apartments and the rich collections of the Museum of Fine Art. The monastery Ground floor I D A Reception-ticket desk 19 B Gift and book shop 18 C Lift 10 D Toilets 11 20 9 8 7 21 E Church 25 24 F 22 H 6 6 F Convent buildings 12 5 and museum 4 2 G Parvis and sundial E 1 H Gardens 23 I Surrounding areas 3 A B C D Key features Entrance Exit 7-9 The tombs G 14 The Princess’s apartments 15 The great hall 16 The monks’ sleeping First Floor quarters Museum 19 What a Project! 17 13 16 15 14 C The Royal Monastery of Brou consists of three cloisters on two levels and over 4,000 m² of buildings for a community of between twelve and thirty monks. -

Bodies of Knowledge: the Presentation of Personified Figures in Engraved Allegorical Series Produced in the Netherlands, 1548-1600

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations 2015 Bodies of Knowledge: The Presentation of Personified Figures in Engraved Allegorical Series Produced in the Netherlands, 1548-1600 Geoffrey Shamos University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations Part of the History of Art, Architecture, and Archaeology Commons Recommended Citation Shamos, Geoffrey, "Bodies of Knowledge: The Presentation of Personified Figures in Engraved Allegorical Series Produced in the Netherlands, 1548-1600" (2015). Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations. 1128. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/1128 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/1128 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Bodies of Knowledge: The Presentation of Personified Figures in Engraved Allegorical Series Produced in the Netherlands, 1548-1600 Abstract During the second half of the sixteenth century, engraved series of allegorical subjects featuring personified figures flourished for several decades in the Low Countries before falling into disfavor. Designed by the Netherlandsâ?? leading artists and cut by professional engravers, such series were collected primarily by the urban intelligentsia, who appreciated the use of personification for the representation of immaterial concepts and for the transmission of knowledge, both in prints and in public spectacles. The pairing of embodied forms and serial format was particularly well suited to the portrayal of abstract themes with multiple components, such as the Four Elements, Four Seasons, Seven Planets, Five Senses, or Seven Virtues and Seven Vices. While many of the themes had existed prior to their adoption in Netherlandish graphics, their pictorial rendering had rarely been so pervasive or systematic. -

Brussels 1 Brussels

Brussels 1 Brussels Brussels • Bruxelles • Brussel — Region of Belgium — • Brussels-Capital Region • Région de Bruxelles-Capitale • Brussels Hoofdstedelijk Gewest A collage with several views of Brussels, Top: View of the Northern Quarter business district, 2nd left: Floral carpet event in the Grand Place, 2nd right: Brussels City Hall and Mont des Arts area, 3rd: Cinquantenaire Park, 4th left: Manneken Pis, 4th middle: St. Michael and St. Gudula Cathedral, 4th right: Congress Column, Bottom: Royal Palace of Brussels Flag Emblem [1] [2][3] Nickname(s): Capital of Europe Comic city Brussels 2 Location of Brussels(red) – in the European Union(brown & light brown) – in Belgium(brown) Coordinates: 50°51′0″N 4°21′0″E Country Belgium Settled c. 580 Founded 979 Region 18 June 1989 Municipalities Government • Minister-President Charles Picqué (2004–) • Governor Jean Clément (acting) (2010–) • Parl. President Eric Tomas Area • Region 161.38 km2 (62.2 sq mi) Elevation 13 m (43 ft) [4] Population (1 January 2011) • Region 1,119,088 • Density 7,025/km2 (16,857/sq mi) • Metro 1,830,000 Time zone CET (UTC+1) • Summer (DST) CEST (UTC+2) ISO 3166 BE-BRU [5] Website www.brussels.irisnet.be Brussels (French: Bruxelles, [bʁysɛl] ( listen); Dutch: Brussel, Dutch pronunciation: [ˈbrʏsəɫ] ( listen)), officially the Brussels Region or Brussels-Capital Region[6][7] (French: Région de Bruxelles-Capitale, [ʁe'ʒjɔ̃ də bʁy'sɛlkapi'tal] ( listen), Dutch: Brussels Hoofdstedelijk Gewest, Dutch pronunciation: [ˈbrʏsəɫs ɦoːft'steːdələk xəʋɛst] ( listen)), is the capital -

The Lives of the Saints. with Introd. and Additional Lives of English Martyrs, Cornish, Scottish, and Welsh Saints, and a Full I

* -* This Volume ronttiim Two Indices to the Sixteen Volumes of the work, one an Index of the Saints whose Lives are given, ami the other a Subject Index. First Edition fiiHished rSyj Second Edition , iSgy .... , New and Hevised Kditioti, i6 vols. ,, i9^'t- *- Appendix Vol. , Fronlispiece.j ^^^' * ' * THE 5LitiC0 of t|)c ^aint0 BY THE REV. S. BARINCJ-GOUU:), M.A. With Introduction and Additional Lives of English Martyrs, Cornish, Scottish, and Welsh Saints, and a full Index to the Entire Work New and Revised Edition ILLUSTRATED BY 473 ENGRAVINGS VOLUME THE SIXTEENTH SlppruDix Foluiuf EDINBURGH: JOHN GRANT 31 GEORGE IV BRIDGE 1914 * * BX 63 \ OjlLf Printed liy BAi.t.ANiVNK, Hanson »V Co. at the Dallaitlync Press, ICJinljurgh I *- -* CONTENTS PAGHS The Celtic Church and its Saints . 1-86 Brittany : its Pkincks and Saints . Pi uiGREES OF Saintly Families .... A Celtic and Eni;lish Kalendar of Saints Proper to the Welsh, Cornish, Scottish, Irish, Breton, and English People . Catalogue of the Materials Available for THE Pedigrees of the British Saints Err.\ta Index to Saints whose Lives are Given Index to Subjects -* VI Contents LIST OF ADDITIONAL LIVES C.IVEN IN THE CELTIC AND ENGLISH KALENDAR S, Calhvcn 288 S. Aaron 245 Cano}; 279 „ Ai'lliaiani .... 288 Caranoy or Carantoji 222 „ Alan 305 Caron '93 „ Aidan 177 Callian ., Albuiga .... 324 Calliciinc Aiidlcy 314 „ Alilalc 179 Cawrdaf 319 „ Alfred tlie Great . 285 Ceachvalla 213 „ Alfric 305 Ceitlio . 287 „ Alnicdlia .... 258 Cclynin, son of „ Aniacllilu .... 325 Cynyr F irfdrwcli 287 „ Arniel 264 Celynin, son of „ Arniilf 268 Ilelig 3'o „ Austell 243 Cewydd 245 „ Auxilius . -

Heritage Days 16 & 17 Sept

HERITAGE DAYS 16 & 17 SEPT. 2017 | NATURE IN THE CITY Info Featured pictograms Organisation of Heritage Days in Brussels-Capital Region: Regional Public Service of Brussels/Brussels Urbanism and Heritage Opening hours and dates Department of Monuments and Sites a CCN – Rue du Progrès/Vooruitgangsstraat 80 – 1035 Brussels M Metro lines and stops Telephone helpline open on 16 and 17 September from 10h00 to 17h00: 02/204.17.69 – Fax: 02/204.15.22 – www.heritagedays.brussels T Trams [email protected] – #jdpomd – Bruxelles Patrimoines – Erfgoed Brussel The times given for buildings are opening and closing times. The organisers B Bus reserve the right to close doors earlier in case of large crowds in order to finish at the planned time. Specific measures may be taken by those in charge of the sites. g Walking Tour/Activity Smoking is prohibited during tours and the managers of certain sites may also prohibit the taking of photographs. To facilitate entry, you are asked to not Exhibition/Conference bring rucksacks or large bags. h “Listed” at the end of notices indicates the date on which the property described Bicycle Tour was listed or registered on the list of protected buildings. b The coordinates indicated in bold beside addresses refer to a map of the Bus Tour Region. A free copy of this map can be requested by writing to the Department f of Monuments and Sites. Guided tour only or Please note that advance bookings are essential for certain tours (reservation i bookings are essential number indicated below the notice). This measure has been implemented for the sole purpose of accommodating the public under the best possible conditions and ensuring that there are sufficient guides available. -

635 List of Illustrations

Cross, northern Netherlands (county of LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS Holland), c. 1500−30. Boxwood, diam. 50 mm. Copenhagen, Statens Museum FIG. 1 for Kunst, inv. no. KMS 5552 (cat. no. 14) Adam Dircksz and workshop, Prayer Nut with Scenes from the Life of Mary FIG. 9 Magdalen and St Adrian of Nicomedia Adam Dircksz and workshop, Devotional (closed), northern Netherlands (county Tabernacle with the Crucifixion, the of Holland), c. 1519−30. Boxwood, Entombment, and Other Biblical Scenes, diam. 65 mm. Riggisberg, Abegg-Stiftung, northern Netherlands (county of Holland), inv. no. 7.15.67 (cat. no. 32) c. 1510−30. Boxwood, h. 267 mm. Vienna, Hofgalerie Ulrich Hofstätter (cat. no. 40) FIG. 2 Prayer Nut with Scenes from the Life FIG. 10 of Mary Magdalen and St Adrian of Adam Dircksz and workshop, Triptych Nicomedia (fig. 1), open with the Virgin in Sole and Saints, northern Netherlands (county of Holland), FIG. 3 c. 1500−30. Boxwood, h. 185 mm. Adam Dircksz and workshop, Prayer Nut Amsterdam, Rijksmuseum, with the Crucifixion, the Carrying of the inv. no. BK-BR-946-h; on permanent loan Cross, and Other Biblical Scenes, northern from Museum Catharijneconvent, Utrecht, Netherlands (county of Holland), c. 1500−30. since 2013 (cat. no. 48) Boxwood, diam. 69 mm. Munich, Schatzkammer der Residenz, inv. no. FIG. 11 ResMü.Schk.0029 WAF (cat. no. 28) Adam Dircksz and workshop, Triptych with the Nativity, the Annunciation to the FIG. 4 Shepherds, and Other Biblical Scenes, Jan Gossaert, Virgin and Child, Utrecht, northern Netherlands (county of Holland), c. 1522. Oil on panel, 38.5 x 30 cm. -

Large Print Guide

The Waddesdon Bequest Funded by The Rothschild Foundation Contents Section 1 5 Section 2 9 Section 3a 13 Section 3b 27 Section 4a 43 Section 4b 61 Section 5a 75 Section 5b 91 Section 6a 101 Section 6b 103 Section 6c 107 Section 6d 113 Section 6e 119 Section 6f 123 Section 6g 129 Section 6h 135 Section 7a 141 Section 7b 145 Section 7c 149 Section 7d 151 Section 7e 153 Section 7f 157 Section 7g 163 Section 7h 169 Section 7i 173 Section 7j 179 Section 8 187 Entrance 8 2 3a 7j 1 7i 7h 3b 6a 7g 4a 6b 7f 6c 7e 6d 7d 4b 6e 7c 5a 6f 7b 6g 7a 6h 5b 4 Section 1 Entrance 8 2 3a 7j 1 7i 7h 3b 6a 7g 4a 6b 7f 6c 7e 6d 7d 4b 6e 7c 5a 6f 7b 6g 7a 6h 5b 5 The Waddesdon Bequest is a collection of outstanding quality generously bequeathed to the British Museum in 1898 by Baron Ferdinand Rothschild MP (1839–1898). It is a family collection, formed by a father and son: Baron Anselm von Rothschild (1803–1874) of Frankfurt and Vienna, and Baron Ferdinand, who became a British citizen in 1860, and a Trustee of the British Museum in 1896. Named after Baron Ferdinand’s Renaissance-style château, Waddesdon Manor in Buckinghamshire, the Bequest is a 19th-century recreation of a princely Kunstkammer or ‘art chamber’ of the Renaissance. The collection demonstrates how, within two generations, the Rothschilds expanded from Frankfurt to become Europe’s leading banking dynasty. -

RAYMOND V. SCHODER, S.J. (1916-1987) Classical Studies Department

y RAYMOND V. SCHODER, S.J. (1916-1987) Classical Studies Department SLIDE COLLECTION OF FIFTH CENTURY SCULPTURES 113 slides Prepared by Laszlo Sulyok Ace. No. 89-15 Computer Name:SCULPTSC.SCH 1 Metal Box Loca lion: 17B The following slides of Fifth Century Sculptures arc from the collection of Fr. Raymond V. Schoder, S.J. They are arranged numerically in the order in which they were received at the archives. The list below provides a brief description of the categorical breakdown of the slides and is copied verbatim from Schoder's own notes on the material.· The collection also contains some replicas of the original artifacts. I. SCULPT: Owl, V c (A crop.) # 2. SCULPT: 'Leonidas' (Sparta) c.400 3. SCULPT: Vc: Boy ded. by Lysikleidcs at Rhamnous, c. 420:30" (A) 4. SCULPT: Vc. Girl, Rhamnous (A) 5. SCULPT: V c. hd, c.475 (Cyrene) 6. SCULPT: Peplophoros * B arberini, c. 475 (T) 7. SCUPLT: Horse, fr. Thasos Hcracles T. pediment, c. 465 (Thas) 8. SCULPT: Base for loutrophoros, Attic, c. 410: Hermes (1), Dead w. apples (Elysian?) (A) 9. SCULPT: Aphrod. on Turtle, aft. or.c. 410 1459 (E. Berlin) 10. SCULPT: fem. fig. fr. frieze Arcs T? (Ag) II. SCULPT: V c. style hd: Diomedes (B) 12. SCULPT: v C. Hercules (Mykonos) 13. SCULPT: V c. style goddcs hd. colossal: Roman copy (Istb) 14. SCULPT: Vc Goddes; Farn. 6269; Rom. (N) 15. SCULPT: Gk. Here. pre-Lysippus (Csv) 16. SCULPT: Choiseui-Gouffier Apollo·· aft early V c (BM) 17. SCULPT: Choiseui/Gouffier Apollo, c. 460 (BM) 18. -

Downloaded from Brill.Com09/23/2021 10:21:27AM Via Free Access Chapter 4 Pilgrimage

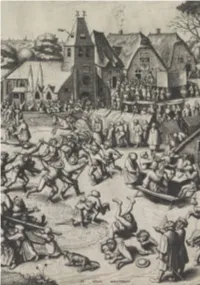

Ruben Suykerbuyk - 9789004433106 Downloaded from Brill.com09/23/2021 10:21:27AM via free access Chapter 4 Pilgrimage The Public Debate on Images, Miracles and Pilgrims The direct causes of the 1566 Beeldenstorm were diverse and cannot possibly be reduced to a single factor, but the acts themselves were a physical and material expression of a body of critiques that had become common ground among Protestants all over Europe. One of the most controversial subjects was the veneration of saints, relics and images, which, in turn, were the driving force behind the pil- grimage phenomenon. Harking back to the ban on the making and adoration (adorare in the Vulgate, latreia in the Septuagint) of imag- es (resp. sculptile or eidolon) in the Ten Commandments (Exodus 20, 1–17; Deuteronomy 5, 4–21), Protestant reformers judged their use and paying honor to them to be idolatrous, distracting the attention of the people from the genuine devotion to God. Luther, Zwingli and Calvin all fulminated against such Catholic practices, although their individual standpoints significantly differed, varying from rather tolerant in Luther’s case to virtually encouraging iconoclasm in the case of Zwingli.1 Protestant Critiques After his initial fierce criticism, Luther developed an increasingly moderate attitude. In the series of sermons he held in Wittenberg in early March 1522 to end the disorderly course of the Unruhen, he presented images as adiaphora, things that in themselves are neither good nor bad. His key distinction was between exterior idolatry, di- rected to images, and the much more dangerous interior cult of idols ‘which every person [has] in his or heart’, such as money.2 Inasmuch as images could help believers to worship God, they were certainly to be allowed in Luther’s view.