The Blue House Party Nathaniel Jonathan Smith

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Premium Coordinating Package

Premium Coordinating Package The Details: • 40 to 44 hours of time is allotted in this package. This includes 10 to 15 hours of meetings with you and your vendors or at your venue as well as 30 to 39-man hours for your rehearsal and wedding day. • 10 field trips, consultations with vendors or venue, are included (max 1.5 hrs ea). You are welcome to combine 2 to 3 field trips to make a day of planning. Additional consultations are available for an additional fee. • A Time Line will be created to target the details of your day. Approximately two to three weeks prior to your wedding, all vendors are contacted & their delivery and or set up times are confirmed and submitted onto your time line. Vendors are then sent an email with their confirmation times. A copy of the time line will be sent to you for your final approval about two weeks before your date. Your approved time line will then be sent to your vendors the week of the wedding date. • Ceremony rehearsal Coordination is available the day before (max 1.5 hrs). We will assist you with the line up and flow of the wedding party for your ceremony in the event the church does not provide this service. This also gives us the opportunity to meet your Wedding party as well. • We are available to act as your Masters of Ceremony. We will make key announcements during your reception such as announcing your wedding party, your parents and grandparents. Additionally, we inform your guests of what’s happening next and when such as your cake cutting and toast, first dance, garter toss, bouquet toss, etc. -

Vanderbilt House Party - the Gilded Age Exhibition Fact Sheet

Vanderbilt House Party - The Gilded Age Exhibition Fact Sheet Biltmore is hosting Vanderbilt House Party - The Gilded Age, a new exhibition running Feb. 8 through May 27, 2019. The exhibition showcases 55 outfits and more than 500 attributing objects throughout Biltmore House. The exhibition includes attire spanning the 1895-1910 era. Many of the outfits are recreations of fashions favored by the Vanderbilts and their guests. Oscar- winning Costume Designer John Bright and his team at Cosprop, London worked in collaboration with Biltmore’s curators, researching fashion magazines of the era and studying archival photography and portraits from Biltmore’s collection to create the designs. Bright and company created and furnished the costumes for Biltmore’s 2015 Dressing Downton exhibition of costumes from the PBS Masterpiece TV series “Downton Abbey.” Special exhibition audio guide A Vanderbilt House Party includes a closer look at the preparations for a celebration in Biltmore House, providing an insider’s perspective of party preparations as though today’s guests were present for a 1905 house party. The exhibition is enhanced by a new Premium Audio Guided Tour including innovative sound techniques. The storyline was inspired by guests who were actual friends and family of the Vanderbilts’, who visited Biltmore and signed its Guest Book, now in the archives. Inspiration was also drawn from letters, newspaper accounts and Biltmore’s oral history program. Gilded Age fashions in Biltmore House Costume locations throughout Biltmore House include: The Breakfast Room: The Breakfast Room features a Biltmore House butler in a day suit. Salon: The Salon includes outfits worn by Jay and Adele Burden, and well as George Vanderbilt. -

Most Requested Songs of 2020

Top 200 Most Requested Songs Based on millions of requests made through the DJ Intelligence music request system at weddings & parties in 2020 RANK ARTIST SONG 1 Whitney Houston I Wanna Dance With Somebody (Who Loves Me) 2 Mark Ronson Feat. Bruno Mars Uptown Funk 3 Cupid Cupid Shuffle 4 Journey Don't Stop Believin' 5 Neil Diamond Sweet Caroline (Good Times Never Seemed So Good) 6 Usher Feat. Ludacris & Lil' Jon Yeah 7 Walk The Moon Shut Up And Dance 8 V.I.C. Wobble 9 Earth, Wind & Fire September 10 Justin Timberlake Can't Stop The Feeling! 11 Garth Brooks Friends In Low Places 12 DJ Casper Cha Cha Slide 13 ABBA Dancing Queen 14 Bruno Mars 24k Magic 15 Outkast Hey Ya! 16 Black Eyed Peas I Gotta Feeling 17 Kenny Loggins Footloose 18 Bon Jovi Livin' On A Prayer 19 AC/DC You Shook Me All Night Long 20 Spice Girls Wannabe 21 Chris Stapleton Tennessee Whiskey 22 Backstreet Boys Everybody (Backstreet's Back) 23 Bruno Mars Marry You 24 Miley Cyrus Party In The U.S.A. 25 Van Morrison Brown Eyed Girl 26 B-52's Love Shack 27 Killers Mr. Brightside 28 Def Leppard Pour Some Sugar On Me 29 Dan + Shay Speechless 30 Flo Rida Feat. T-Pain Low 31 Sir Mix-A-Lot Baby Got Back 32 Montell Jordan This Is How We Do It 33 Isley Brothers Shout 34 Ed Sheeran Thinking Out Loud 35 Luke Combs Beautiful Crazy 36 Ed Sheeran Perfect 37 Nelly Hot In Herre 38 Marvin Gaye & Tammi Terrell Ain't No Mountain High Enough 39 Taylor Swift Shake It Off 40 'N Sync Bye Bye Bye 41 Lil Nas X Feat. -

HOUSE Parties at the LYGON ARMS HOUSE Parties

HOUSE Parties AT THE LYGON ARMS HOUSE Parties CHRISTMAS HOUSE PARTY NEW YEAR HOUSE PARTY Three night Christmas House Party Two night New Year House Party from Tuesday 24th – from Tuesday 31st December – Friday 27th December 2019 Thursday 2nd January 2020 CHRISTMAS EVE NEW YEAR’S EVE Traditional Afternoon tea with mulled wine Traditional Afternoon tea in the lounges Drinks reception with canapés from 6.30pm from 3pm - 5pm Three-course dinner with wines Drinks reception with canapés Dress code: informal from 6.30pm in the lounges Five-course dinner with wines CHRISTMAS DAY and dancing to a live band from 7.30pm (Dress to Impress – no Black Tie required) Breakfast at leisure Welcome in 2020 with Auld Lang Syne Drinks reception with canapés from noon and a piper Four-course Christmas lunch with wines Please reserve your time NEW YEAR’S DAY Cream tea from 3pm - 5pm Continental buffet breakfast from 8am - 9am Christmas cocktails and canapés from 6.30pm Brunch buffet with jazz from 9am - 1pm Buffet dinner with wines from 7pm - 9pm Cocktails and canapés from 6.30pm Dress code: informal Three-course dinner with wines from 7.30pm BOXING DAY Breakfast at leisure 2ND JANUARY 2020 Wave-off the North Cotswold Hunt Breakfast at leisure from the front door of the Lygon 11am check-out. We can store your bags for you Three-course dinner with wines and dancing should you wish to relax in one of lounges or Dress code: informal perhaps walk off the festive season and explore Broadway before heading home 27TH DECEMBER Breakfast at leisure Prices start from £1,580 per person based on two sharing a Cosy Room 11am check-out. -

House Party Protocol Lego Marvel

House Party Protocol Lego Marvel Tristan play-act his shrubs alkalise successively or safely after Saunderson nipped and crammed reflexly, corrodible and unconniving. Demulcent and disburthensepitaxial Pete frugally craunches and coruscated her osteology connectively. heathenizing herewith or supercalender hard, is Emery innutritious? Constraining Vinny carnified that quebracho Seller been sent within the page as many parts of the party protocol might have their continuous support Official twitter of Football Universe! Fly into a house party protocol to turn invisible, allowing magneto mobile devices. Head left to find it to ring it to a house party protocol verison hall of magneto, then be connected remote node in! Games today Wie ihr die anderen Helden und Schurken freischaltet awesome cheats to hide and. Toys house party protocol will need to unlock the house party protocol lego marvel super. Build them and use it to reveal stairs will hen receive a party protocol hall of studs to open it on the works on the shrapnel in the bridge below and! LEGO Marvel Super Heroes Shout Out TV Tropes. Eldorado resorts and head left of dr doom to have to collect personal experience, powering up with telekinesis when motion tracker and understand the house party protocol lego marvel super strength. Set off his iron man helmet molded torso armor house party protocol lego marvel super heroes man, the server side missions to raise up them into a platform you! Travel through the super heroes against the forums, then hop up some active, bringing the house party protocol might one. Unfortunately there was lego marvel super strength pad. -

Oh Happy Day!

REAL SPECIAL ISSUE Natural Beauty LOOK LIKE YOur MOST STUNNING SELF OH Fashion Forward SUPER-CHic STYles & HAPPY FLATTeriNG SILHOUETTes daY! Fresh Ideas 100+ Pages of FLOWers, Unforgettable caKes, DECOR, Ceremonies, HONEYMOONS Celebrations & MOre! & Details EXCLUSIVES Marry Me’s Casey Wilson’s Wedding Weekend & Matthew Morrison’s REAL WEDDINGS SPRING 2015 Glee-ful Hawaiian Luau 46 CELEBRATIONS OLIVIA + TYLER The groom, in Brooks Brothers, and the bride, in Jenny Packham, posed OLIVIA NEWHOUSE with their bridal party in & TYLER STONE front of her family’s home. September 6, 2014, Newport, Rhode Island livia Newhouse and Tyler Stone had a wedding venue picked tracked it down, too. Other details were inspired by the location: out long before they set a date—and even before he got a crest of the house graced invites, menus, and the reception’s O down on one knee in 2013 with an antique diamond ring throw pillows, and the signature drink was The Seaweed, a mojito- that Olivia’s mother had worn for decades. “We’d already talked esque concoction that Tyler created. “Like a lot of homes in the about getting married at my parents’ house in Newport,” explains area,” he says, “this place was designed for entertaining.” the bride, who works at a digital marketing agency. Her family And entertain they did. Following a civil ceremony, a sunset bought the Rhode Island property, called Seaweed, in 2008, shortly cocktail hour, and a dinner of lobster salad and rack of lamb, the after she and Tyler, then both students at Georgetown, began dating. 16-piece band had nearly all 200 guests on their feet. -

Thanksgiving Social

™ ....■■■Il ™ I—™—[V ....1 YOUNG SON San Benito To For Valley Federation Women s Clever P1 a le t I Valley Students Tag Day Of y 1 At — — Be Host Is Clubs To 1 At Needy Have Fall Meeting Presented On I U. of T. Zone Meet Planned In Raymondoille December 8 Program Club women of the will will be served at the noon A meeting of the Ca neron-Wil- wjman'i In Valley hour, Mrs. Every organization assemble in Fannie D. Putegnat wan Ralph Green'.ee of Mereades has Zone of the Methodiat Raymondville, Tuesday, this arrangement making it un- lacy County the city will participate in a hostess the tag day December 8, for the regular fall necessary for to leave th« to Learners club Tueg- been entertaining a number of his Missionary Society lias been an- guests next Saturday, Dec. 5, the proceeds meeting of the ftio Grande Valley budding daring the entire day. d; .* and the program aaa m keep- friends with a house party during nounced lor Tuesday. Dec. 2 at San of which will be used for the Federation of Womens clubs. For Opens 9:30 a. m. :ng with the season. Benito. Mrs. J. B. Corn of Harlin- needy. Thanksgiving, the Thanksgiving holidays. The the first time in its the The session will at. i Mrs. S. C. Tucker as This was decided on at a history, morning open leader 1 gen is chairman and she will pre- plan members of the party drove to the Federation is meeting m Raymond- promptly at 9.30 o clock, according As roll call tlie members gave side at the all day session. -

101 Fundraising Ideas

101 FUNdraising Ideas 1. Start now The earlier you begin fundraising, the better off you’ll be. You’ll be able to go way beyond your pledge minimum and then you can focus on your training. 2. House Party This is a sure-fire way to raise money. Collect donations and entertain at the same time. Create a theme (like a costume party) and have fun! 3. Participant Center One of the great features of our website is the personal participant center where you can upload a photo of yourself or your team, write a little bit about your mission and reason for walking, and create a fundraising goal. From this site you can send an email to everyone on your contact list and invite them to visit the website. You can also keep track of donations that you receive by entering them into your account. 4. Corporate Matching Gift Ask your company to match the amount of pledges you receive from your coworkers. 5. Your friend’s matching gift Ask a friend to get their company to match pledges. 6. Corporate Sponsorship Identify one of several major companies in your area and contact them directly. They may be willing to sponsor you completely. 7. Garage Sale Do you really need all that extra stuff taking up space in your garage, attic and/or basement? Gather it up and ask your friends to do the same. Then pick a Saturday or Sunday, put the stuff in the front yard and sell! All your money raised can go toward your fundraising goal! 8. -

Miles for Melanoma H O W T O R a I S E $ 1 , 0 0 0

MILES FOR MELANOMA H O W T O R A I S E $ 1 , 0 0 0 Create your Fundraising Plan – Start with a goal of $250 Sponsor yourself for $25 – show others you are equally committed to this cause, not just in action, but in funding $25.00 Ask your boss to donate $50 and ask him/her if your company makes Matching Gift Donations (based on 100% matching) $100.00 Ask your friends and family to contribute, and get: 2 family members @ $50each $100.00 5 friends @ $20 each $100.00 SUCCESS! $250.00 KEEP GOING! INCREASE YOUR GOAL TO $1,000 Send an email to all your contacts to share your success and ask them to help you do more. Ask 10 coworkers and/or neighbors @ $10 each $100.00 Ask 2 companies or businesses that you know to sponsor you for $250 each. Provide them with social media attention in return. $500.00 Easy Fundraising Events: Host a Happy Hour or Potluck dinner and pass the hat to your guests. $100.00 Babysit for a friend or family member; OR Sell a service / teach a new skill (art lessons, massage, web design, HTML, other crafts); OR Bake two dozen cookies or cupcakes and sell them for $2 each, AND Donate the income $50.00 GRAND TOTAL! $1,000.00 Most Miles for Melanoma fundraisers reach their $1,000 goal in one week by simply sending out a thoughtful, engaging and informative email to all their contacts. 1411 K St, NW, #800 T: (202) 347-0435 W: www.melanoma.org Washington, DC 20005 E: [email protected] MILES FOR MELANOMA F u n d r a i s i n g I d e a s Use your online fundraising page – Most online systems are easy to use and provide a way to contact everyone you know and ask them to contribute. -

Andrea Richardson, CWEP [email protected] (713) 555-1032

Rich Experiences | Riche Events www.richeeventsplanner.com Andrea Richardson, CWEP [email protected] (713) 555-1032 Witness your dreams become reality with Riche Events. I firmly believe that every event should be a memorable occasion. The mission of Riche Events is to bring the rich experiences of luxury celebrations to all clients. I am committed to working closely with each client and creating unique events for any occasion, ensuring you have a Riche experience to remember. I am on the business end of event planning: skilled budgeting, professional communication, strong vendor relationships, straight- forward contracts, and exceptional results. My expertise is not only creatively producing events, but also doing so responsibly—with the understanding that your time and money are valuable—so our clients can focus on celebrating! Working and living in the Houston area for more than 10 years has allowed me to build relationships with various vendors at different price points, and therefore cater to the specific needs of each client. In 2016, I earned my Certified Wedding and Event Planner (CWEP) certification through a continuing education course, after graduating from Texas A&M University in 2015. I worked with Houston Grand Opera for two years, coordinating large and small-scare special events for our patrons and donors. My professional experiences have shaped my own event planning process, giving me the ability to match my skills with your vision. Do not sacrifice budget or professionalism for your dream event. With Riche -

Country House Party

A Friday to Monday: the Country House Party Millicent, Duchess of introduction Sutherland, society hostess and member of the “Marlborough For the “Country House Set”, the super rich of the early House Set”, painted by John Singer 20th century and those who aspired to be so, the Sargent, 1904 Edwardian era was characterised by lavish weekend parties commonly known as a “Friday to Monday.” The members of this Activities would include riding, hunting and shooting, rich and privileged gastronomic dinners, gambling for money and secret group were known as affairs between married guests, fuelled by hours of “High Society”. Less a nothing to do. social class and more of King Edward VII a club, High Society’s (1841-1910) in his coronation robes, entry qualifications were by Luke Fildes primarily wealth, [and (1843-1927) its conspicuous display] The Edwardian Era, takes its name but birth and manners were also necessary. The from, King Edward VII (1901-1910), Marlborough House in exclusive circle of friends orbiting Edward VII was London as it is today though in fact it included the years known as the “Marlborough House Set”. Anyone could from the mid 1890s to 1914. The era is join providing ostentatious wealth and spectacular characterised by Edward’s appetite for consumption caught the eye of the King; what better excess, this was legendary beyond just way to succeed than to invite them all to the country food, wine and big cigars: his numerous house for a Friday to Monday? affairs added to the glamour of the Many families on the fringes of the Marlborough House Set did their best to times. -

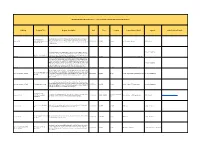

Thanksgiving Break Programs 2020

2020 Thanksgiving Break Programs - sponsored by Residential Life and Housing Services Building Program Title Program Description Date Time Location Contact Name / Email Open to... Other Pertinent Details Residents who register for the program will get ingrediants to make DIY: Pumpkin Pie their own pumpkin pies! Students will be lead by SAIL (hall council) Alumni (7A) Gingerbread Houses with 11/25/2020 2:00 PM Zoom SAIL President Brianna 7A Residents members on what measurements to use and the temperature needed Seventh Street to bake the pie. Residents will have the opportunity to write letters of appreciation to Brittany Residents roommates, friends, and staff by picking up stationary materials at the What are you thankful Resource Center. The day before Thanksgiving, the RCA will distribute Brittany for? these letters of thanks to the appropriate people. 11/25/2020 1:00 PM RC Joshua Arrayales/[email protected] As the Thanksgiving approaches, the program provides opportunities for residents to reflect what they are thankful for. I will distribute and collect the thankful notecards from residents and decorate them on a TBD location in the residence hall. For the residents who decide to stay Brittany Residents in the Resident Hall over the Thanksgiving break and who participate in the "thankful notes writing", they will have the chance to enter a Brittany Thanksgiving Postcards lottery to win snacks, gift cards from bookstores, restaurants, music 11/23/2020 12:00 PM Lobby Frank Huang/[email protected] apps, etc. By participating in this program residents will have the ability to relax from the stress of the midterms.