For Mixed Martial Arts Andrew Zerling

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sumo Manga by P.M.B.Q

YOI-SHO!! What the audience shouts when the wrestlers kick their leg up and stomp the ground. www.sakuraofamerica.com ©Sumo Manga by P.M.B.Q. Studios Table of Contents Table 1 History of Nihon Sumo Kyokai History of 2 Banzuke: The Offi cial Sumo Ranking Record Nihon Sumo Kyokai 3 The Ranking Pyramid 4 Sumo Attire 5 Basho: Offi cial Tournament Competition 6 Dohyo: The Sumo Ring 7 Traditional Ceremonies 9 Gyoji and Judges 10 Sumo Wrestling Begins 11 Tournament Rules 12 Words to Know Sumo is an ancient sport dating patron for sumo wrestling, back some 1500 years. The fi rst and established the fi rst rules sumo matches were a form of ritual and techniques. dedicated to the gods along with prayers for a bountiful harvest. During a long period of warfare, Together with ritual dancing and the military trained soldiers in dramas, sumo was performed in sumo, and jujitsu was formed by religious shrines. the samurai as an off shoot of sumo. When peace was fi nally In the Nara Period in the 8th restored in 1603, a period of Century, sumo wrestling became prosperity grew, and the merchant History of Nihon Sumo Kyokai an annual festival which included classes organized professional wrestling matches and the winning sumo groups for their entertainment, sumo wrestlers participated in music and has further developed into the and dancing celebrations. The sumo wrestling sport enjoyed in Imperial Court was the sponsor or modern times. 1 Banzuke: The Official The Ranking Sumo Ranking Record Pyramid Today there are No weight limits exist in sumo The lower ranks, Sandanme (san- about 800 rikishi wrestling, so a rikishi (wrestler) dan-me), Jonidan (jo-ni-dan), and (wrestlers) in could face an opponent that Jonokuchi (jo-no-kuchi) do not weighs twice as much as his own wrestle each day of a tournament. -

Student Manual

Student Manual UNITED STATES ACADEMY OF MARTIAL ARTS 21 ZACA #100, SAN LUIS OBISPO, CA 9341 805-471-3418 www.us-ama.com PARENTS FREE MONTH One free month of training for any parent(s) of a current US-AMA student! 28 ADDITIONAL TRAINING CONTENTS AIDS Welcome!............................................................................................................1 (Available through the Dojo Office) What is the United States Academy of Martial Arts…………………………..2 Along with your regular class instruction it is important that you practice your What Our Students Have to Say……………………………………………….4 techniques at home. Since we all know that it is easy to forget a particular move or block, US-AMA has produced training films to help you progress Questions & Answers………………………………………………………….6 through each rank. US-AMA Instructors…………………………………………………………..8 Adult Classes and Family Self-Defense……………………………………….9 From a Woman’s point of View…………………………………..…9 A Male Perspective………………………………………………....10 Physical and Mental Benefits……………………………………………...…11 Children’s Program…………………………………………………………..12 Team Ichiban………………………………………………………………....14 Guide for Parents……………………………………………………………..15 Karate Buck Program……………………………………………………...…17 The Picture of the True Martial Artist………………………………………..18 Rules and Regulations……………………………………………………..…19 Attitude and Respect…………………………………………….….19 Dojo Etiquette……………………………………………………....19 A Word about Testing and Rank Advancement……………………………...22 White Belt Bar Requirements…………………………………....…22 Beginning Terminology……………………………………………………...24 -

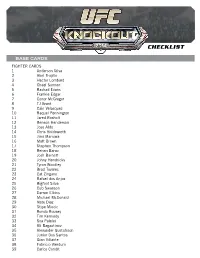

2014 Topps UFC Knockout Checklist

CHECKLIST BASE CARDS FIGHTER CARDS 1 Anderson Silva 2 Abel Trujillo 3 Hector Lombard 4 Chael Sonnen 5 Rashad Evans 6 Frankie Edgar 7 Conor McGregor 8 TJ Grant 9 Cain Velasquez 10 Raquel Pennington 11 Jared Rosholt 12 Benson Henderson 13 Jose Aldo 14 Chris Holdsworth 15 Jimi Manuwa 16 Matt Brown 17 Stephen Thompson 18 Renan Barao 19 Josh Barnett 20 Johny Hendricks 21 Tyron Woodley 22 Brad Tavares 23 Cat Zingano 24 Rafael dos Anjos 25 Bigfoot Silva 26 Cub Swanson 27 Darren Elkins 28 Michael McDonald 29 Nate Diaz 30 Stipe Miocic 31 Ronda Rousey 32 Tim Kennedy 33 Soa Palelei 34 Ali Bagautinov 35 Alexander Gustafsson 36 Junior Dos Santos 37 Gian Villante 38 Fabricio Werdum 39 Carlos Condit CHECKLIST 40 Brandon Thatch 41 Eddie Wineland 42 Pat Healy 43 Roy Nelson 44 Myles Jury 45 Chad Mendes 46 Nik Lentz 47 Dustin Poirier 48 Travis Browne 49 Glover Teixeira 50 James Te Huna 51 Jon Jones 52 Scott Jorgensen 53 Santiago Ponzinibbio 54 Ian McCall 55 George Roop 56 Ricardo Lamas 57 Josh Thomson 58 Rory MacDonald 59 Edson Barboza 60 Matt Mitrione 61 Ronaldo Souza 62 Yoel Romero 63 Alexis Davis 64 Demetrious Johnson 65 Vitor Belfort 66 Liz Carmouche 67 Julianna Pena 68 Phil Davis 69 TJ Dillashaw 70 Sarah Kaufman 71 Mark Munoz 72 Miesha Tate 73 Jessica Eye 74 Steven Siler 75 Ovince Saint Preux 76 Jake Shields 77 Chris Weidman 78 Robbie Lawler 79 Khabib Nurmagomedov 80 Frank Mir 81 Jake Ellenberger CHECKLIST 82 Anthony Pettis 83 Erik Perez 84 Dan Henderson 85 Shogun Rua 86 John Makdessi 87 Sergio Pettis 88 Urijah Faber 89 Lyoto Machida 90 Demian Maia -

BISPING: Barnett Needs to Push the Pace Vs. Nelson

FS1 UFC TONIGHT Show Quotes – 9/23/15 BISPING: Barnett Needs To Push The Pace Vs. Nelson Florian: “Uriah Hall Is Too Dangerous To Just Stand and Trade With” LOS ANGELES – UFC TONIGHT host Kenny Florian and guest host Michael Bisping break down the upcoming FS1 UFC FIGHT NIGHT: BARNETT VS. NELSON. Karyn Bryant and Ariel Helwani add reports. UFC TONIGHT guest host Michael Bisping on how Josh Barnett can beat Roy Nelson: “Josh needs to not get hit by the right hand of Roy. He needs to push the pace of the fight, move forward, and push Roy up against fence and brutalize him with knees and elbows like he did with Frank Mir. Most of his finishes came from the clinch position. He finishes fights against the fence. He did that against Frank Mir.” UFC TONIGHT host Kenny Florian on Barnett avoiding Nelson’s knock out power: “Josh doesn’t want to be on the outside where Roy’s right hand can get him. He wants to be on the inside. He’s been busy on the submission circuit. He’s dangerous on the mat and that’s where he wants to get Roy.” Bisping on how Nelson should fight Barnett: “What Roy can’t get is predictable. If he just tries to throw the big right hand, Barnett is going to see it coming. Roy has to mix up his striking. I’m not sure he’s going to go for takedowns. But he has to mix his striking. His right hand and left hooks, to keep Josh at bay.” Florian on Nelson mixing up his strikes: “The knock on Nelson is his lack of evolution. -

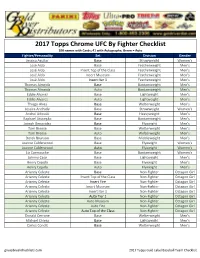

2017 Topps UFC Checklist

2017 Topps Chrome UFC By Fighter Checklist 100 names with Cards; 41 with Autographs; Green = Auto Fighter/Personality Set Division Gender Jessica Aguilar Base Strawweight Women's José Aldo Base Featherweight Men's José Aldo Insert Top of the Class Featherweight Men's José Aldo Insert Museum Featherweight Men's José Aldo Insert Iter 1 Featherweight Men's Thomas Almeida Base Bantamweight Men's Thomas Almeida Auto Bantamweight Men's Eddie Alvarez Base Lightweight Men's Eddie Alvarez Auto Lightweight Men's Thiago Alves Base Welterweight Men's Jessica Andrade Base Strawweight Women's Andrei Arlovski Base Heavyweight Men's Raphael Assunção Base Bantamweight Men's Joseph Benavidez Base Flyweight Men's Tom Breese Base Welterweight Men's Tom Breese Auto Welterweight Men's Derek Brunson Base Middleweight Men's Joanne Calderwood Base Flyweight Women's Joanne Calderwood Auto Flyweight Women's Liz Carmouche Base Bantamweight Women's Johnny Case Base Lightweight Men's Henry Cejudo Base Flyweight Men's Henry Cejudo Auto Flyweight Men's Arianny Celeste Base Non-Fighter Octagon Girl Arianny Celeste Insert Top of the Class Non-Fighter Octagon Girl Arianny Celeste Insert Fire Non-Fighter Octagon Girl Arianny Celeste Insert Museum Non-Fighter Octagon Girl Arianny Celeste Insert Iter 1 Non-Fighter Octagon Girl Arianny Celeste Auto Tier 1 Non-Fighter Octagon Girl Arianny Celeste Auto Museum Non-Fighter Octagon Girl Arianny Celeste Auto Fire Non-Fighter Octagon Girl Arianny Celeste Auto Top of the Class Non-Fighter Octagon Girl Donald Cerrone Base Welterweight -

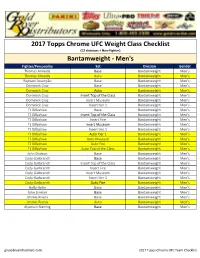

2017 Topps UFC Checklist

2017 Topps Chrome UFC Weight Class Checklist (12 divisions + Non-Fighter) Bantamweight - Men's Fighter/Personality Set Division Gender Thomas Almeida Base Bantamweight Men's Thomas Almeida Auto Bantamweight Men's Raphael Assunção Base Bantamweight Men's Dominick Cruz Base Bantamweight Men's Dominick Cruz Auto Bantamweight Men's Dominick Cruz Insert Top of the Class Bantamweight Men's Dominick Cruz Insert Museum Bantamweight Men's Dominick Cruz Insert Iter 1 Bantamweight Men's TJ Dillashaw Base Bantamweight Men's TJ Dillashaw Insert Top of the Class Bantamweight Men's TJ Dillashaw Insert Fire Bantamweight Men's TJ Dillashaw Insert Museum Bantamweight Men's TJ Dillashaw Insert Iter 1 Bantamweight Men's TJ Dillashaw Auto Tier 1 Bantamweight Men's TJ Dillashaw Auto Museum Bantamweight Men's TJ Dillashaw Auto Fire Bantamweight Men's TJ Dillashaw Auto Top of the Class Bantamweight Men's John Dodson Base Bantamweight Men's Cody Garbrandt Base Bantamweight Men's Cody Garbrandt Insert Top of the Class Bantamweight Men's Cody Garbrandt Insert Fire Bantamweight Men's Cody Garbrandt Insert Museum Bantamweight Men's Cody Garbrandt Insert Iter 1 Bantamweight Men's Cody Garbrandt Auto Fire Bantamweight Men's Holly Holm Base Bantamweight Men's John Lineker Base Bantamweight Men's Jimmie Rivera Base Bantamweight Men's Jimmie Rivera Auto Bantamweight Men's Aljamain Sterling Base Bantamweight Men's groupbreakchecklists.com 2017 Topps Chrome UFC Team Checklist Featherweight - Men's Fighter/Personality Set Division Gender José Aldo Base Featherweight Men's -

Martial Arts from Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia for Other Uses, See Martial Arts (Disambiguation)

Martial arts From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia For other uses, see Martial arts (disambiguation). This article needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. (November 2011) Martial arts are extensive systems of codified practices and traditions of combat, practiced for a variety of reasons, including self-defense, competition, physical health and fitness, as well as mental and spiritual development. The term martial art has become heavily associated with the fighting arts of eastern Asia, but was originally used in regard to the combat systems of Europe as early as the 1550s. An English fencing manual of 1639 used the term in reference specifically to the "Science and Art" of swordplay. The term is ultimately derived from Latin, martial arts being the "Arts of Mars," the Roman god of war.[1] Some martial arts are considered 'traditional' and tied to an ethnic, cultural or religious background, while others are modern systems developed either by a founder or an association. Contents [hide] • 1 Variation and scope ○ 1.1 By technical focus ○ 1.2 By application or intent • 2 History ○ 2.1 Historical martial arts ○ 2.2 Folk styles ○ 2.3 Modern history • 3 Testing and competition ○ 3.1 Light- and medium-contact ○ 3.2 Full-contact ○ 3.3 Martial Sport • 4 Health and fitness benefits • 5 Self-defense, military and law enforcement applications • 6 Martial arts industry • 7 See also ○ 7.1 Equipment • 8 References • 9 External links [edit] Variation and scope Martial arts may be categorized along a variety of criteria, including: • Traditional or historical arts and contemporary styles of folk wrestling vs. -

2016 /2017 NFHS Wrestling Rules

2016 /2017 NFHS wrestling Rules The OHSAA and the OWOA wish to thank the National Federation of State High School Associations for the permission to use the photographs to illustrate and better visually explain situations shown in the back of the 2016/17 rule book. © Copyright 2016 by OHSAA and OWOA Falls And Nearfalls—Inbounds—Starting Positions— Technical Violations—Illegal Holds—Potentially Dangerous (5-11-2) A fall or nearfall is scored when (5-11-2) A near fall may be scored when the any part of both scapula are inbounds and the defensive wrestler is held in a high bridge shoulders are over or outside the boundary or on both elbows. line. Hand over nose and mouth that restricts breathing (5-11-2) A near fall may be scored when the (5-14-2) When the defensive wrestler in a wrestler is held in a high bridge or on both pinning situation, illegally puts pressure over elbows the opponents’s mouth, nose, or neck, it shall be penalized. Hand over nose and mouth Out-of-bounds that restricts Inbounds breathing Out-of-bounds Out-of-bounds Inbounds (5-15-1) Contestants are considered to be (5-14-2) Any hold/maneuver over the inbounds if the supporting points of either opponent’s mouth, nose throat or neck which wrestler are inside or on but not beyond the restricts breathing or circulation is illegal boundary 2 Starting Position Legal Neutral Starting Position (5-19-4) Both wrestlers must have one foot on the Legal green or red area of the starting lines and the other foot on line extended, or behind the foot on the line. -

World Combat Games Brochure

Table of Contents 4 5 6 What is GAISF? What are the World Roles and Combat Games? responsibilities 7 8 10 Attribution Culture, ceremonies Media promotion process and festival events, and production and legacy 12 13 14 List of sports Venue Aikido at the World setup Armwrestling Combat Games Boxing 15 16 17 Judo Kendo Muaythai Ju-jitsu Kickboxing Sambo Karate Savate 18 19 Sumo Wrestling Taekwondo Wushu 4 WORLD COMBAT GAMES WORLD COMBAT GAMES 5 What is GAISF? What are the World Combat Games? The united voice of sports - protecting the interests of International A breathtaking event, showcasing Federations the world’s best martial arts and GAISF is the Global Association of International Founded in 1967, GAISF is a key pillar of the combat sports Sports Federations, an umbrella body composed wider sports movement and acts as the voice of autonomous and independent International for its 125 Members, Associate Members and Sports Federations, and other international sport observers, which include both Olympic and non- and event related organisations. Olympic sports organisations. THE BENEFITS OF THE NUMBERS OF HOSTING THE WORLD THE GAMES GAISF MULTISPORT GAMES COMBAT GAMES Up to Since 2010, GAISF has successfully delivered GAISF serves as the conduit between ■ Bring sport to life in your city multisport games for combat sports and martial International Sports Federations and host cities, ■ Provide worldwide multi-channel media exposure 35 disciplines arts, mind games and urban orientated sports. bringing benefits to both with a series of right- ■ Feature the world’s best athletes sized events that best consider the needs and ■ Establish a perfect bridge between elite sport and Approximately resources of all involved. -

Sports Quiz When Were the First Tokyo Olympic Games Held?

Sports Quiz When were the first Tokyo Olympic Games held? ① 1956 ② 1964 ③ 1972 ④ 1988 When were the first Tokyo Olympic Games held? ① 1956 ② 1964 ③ 1972 ④ 1988 What is the city in which the Winter Olympic Games were held in 1998? ① Nagano ② Sapporo ③ Iwate ④ Niigata What is the city in which the Winter Olympic Games were held in 1998? ① Nagano ② Sapporo ③ Iwate ④ Niigata Where do sumo wrestlers have their matches? ① sunaba ② dodai ③ doma ④ dohyō Where do sumo wrestlers have their matches? ① sunaba ② dodai ③ doma ④ dohyō What do sumo wrestlers sprinkle before a match? ① salt ② soil ③ sand ④ sugar What do sumo wrestlers sprinkle before a match? ① salt ② soil ③ sand ④ sugar What is the action wrestlers take before a match? ① shiko ② ashiage ③ kusshin ④ tsuppari What is the action wrestlers take before a match? ① shiko ② ashiage ③ kusshin ④ tsuppari What do wrestlers wear for a match? ① dōgi ② obi ③ mawashi ④ hakama What do wrestlers wear for a match? ① dōgi ② obi ③ mawashi ④ hakama What is the second highest ranking in sumo following yokozuna? ① sekiwake ② ōzeki ③ komusubi ④ jonidan What is the second highest ranking in sumo following yokozuna? ① sekiwake ② ōzeki ③ komusubi ④ jonidan On what do judo wrestlers have matches? ① sand ② board ③ tatami ④ mat On what do judo wrestlers have matches? ① sand ② board ③ tatami ④ mat What is the decision of the match in judo called? ① ippon ② koka ③ yuko ④ waza-ari What is the decision of the match in judo called? ① ippon ② koka ③ yuko ④ waza-ari Which of these is not included in the waza techniques of -

Sag E Arts Unlimited Martial Arts & Fitness Training

Sag e Arts Unlimited Martial Arts & Fitness Training Grappling Intensive Program - Basic Course - Sage Arts Unlimited Grappling Intensive Program - Basic Course Goals for this class: - To introduce and acclimate students to the rigors of Grappling. - To prepare students’ technical arsenal and conceptual understanding of various formats of Grappling. - To develop efficient movement skills and defensive awareness in students. - To introduce students to the techniques of submission wrestling both with and without gi’s. - To introduce students to the striking aspects of Vale Tudo and Shoot Wrestling (Shooto) and their relationship to self-defense, and methods for training these aspects. - To help students begin to think tactically and strategically regarding the opponent’s base, relative position and the opportunities that these create. - To give students a base of effective throws and breakfalls, transitioning from a standing format to a grounded one. Class Rules 1. No Injuries 2. Respect your training partner, when they tap, let up. 3. You are 50% responsible for your safety, tap when it hurts. 4. An open mind is not only encouraged, it is mandatory. 5. Take Notes. 6. No Whining 7. No Ego 8. No Issues. Bring Every Class Optional Equipment Notebook or 3-ring binder for handouts and class notes. Long or Short-sleeved Rashguard Judo or JiuJitsu Gi and Belt Ear Guards T-shirt to train in (nothing too valuable - may get stretched out) Knee Pads Wrestling shoes (optional) Bag Gloves or Vale Tudo Striking Gloves Mouthguard Focus Mitts or Thai Pads Smiling Enthusiasm and Open-mindedness 1 Introduction Grappling Arts from around the World Nearly every culture has its own method of grappling with a unique emphasis of tactic, technique and training mindset. -

Science of Wrestling

Science of Wrestling Annual Research Review 2008 David Curby Preface This annual publication is dedicated to the pursuit and use of the knowledge surrounding the noble and timeless sport of wrestling. Each year, an annotated bibliography of the scientific research, published in English, during the year in review, will be compiled and shared with those who work in the wrestling community. It is my hope that this work will spark further research, along with helping to educate those who are in a position to apply this knowledge. I am proud to be affiliated with this great sport. Thanks to our national governing body - USA Wrestling. Thanks to the National Coaching Staff for the support that they have given to me. Rich Bender, Mitch Hull, Dave Bennett, Steve Fraser, Momir Petkovic, Ike Anderson, Terry Steiner, and Anatoly Petrosyan always respond to my questions. Congratulations to Zeke Jones, as he assumes his new position of National freestyle coach. I am grateful for the chance to work with Ivan Ivanov and Jim Gruenwald and their outstanding wrestlers at the USOEC in Marquette, Michigan. Thanks to my wife Lynne, and my children Nicholas, Jacob and Courtney, who have been a big part of my work in the sport, and have patiently supported me. Larry Slater has provided most of the action photographs found throughout this document. On the cover are his pictures of noteworthy American wrestlers from 2008. These are Henry Cejudo (Olympic freestyle Gold at 55 kg), Clarissa Chun (World Championship Gold at 48 kg), Randi Miller (Olympic Bronze at 63 kg), and Adam Wheeler (Olympic Greco-Roman Bronze at 96 kg).