Spend, Spend, Spend 3 Sociability May Depend Upon Brain Cells

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

OECD Observer Celebrates 50 Meeting the Global Water Challenge

Norway’s gender experience Euro area: Why solidarity matters Israel’s progress report Special focus: Policymaking and the information revolution No 293 Q4 2012 www.oecdobserver.org OECD Observer celebrates 50 Meeting the global water challenge Nestlé’s Aman Bajaj Sood (left) and farmer Harinder Kaur take part in a Farmer Water Awareness Programme provided near the Nestlé factory in Moga, India. Through our Creating Shared Alongside our other CSV key > Public policy Value reporting, we aim to share focus areas of nutrition and > Collective action information about our long-term rural development, this year’s > Direct operations impact on society and how this report summarises Nestlé’s > Supply chain is linked to the creation of our response to the water challenge > Community engagement long-term business success. in five key areas: Visit the CSV Section of our website for a complete report of our progress, challenges and performance in 2011 www.nestle.com /csv CONTENTS No 293 Q4 2012 Meeting the global water challenge READERS’ VIEWS 20 Combating terrorist fi nancing in the 2 Corporate tax responsibility; Labour advice information age Rick McDonell, Executive Secretary, EDITORIAL Financial Action Task Force 3 From the information revolution to 21 Africa.radio a knowledge-based world Roman Rollnick, Chief Editor, Advocacy, Angel Gurría Outreach and Communications, UN-Habitat 22 Is evidence evident? NEWS BRIEF Anne Glover, Chief Scientifi c Adviser to the 4 Crisis drives up social spending–as tax President of the European Commission revenues -

Mcmenamin FM

The Garden of Ediacara • Frontispiece: The Nama Group, Aus, Namibia, August 9, 1993. From left to right, A. Seilacher, E. Seilacher, P. Seilacher, M. McMenamin, H. Luginsland, and F. Pflüger. Photograph by C. K. Brain. The Garden of Ediacara • Discovering the First Complex Life Mark A. S. McMenamin C Columbia University Press New York C Columbia University Press Publishers Since 1893 New York Chichester, West Sussex Copyright © 1998 Columbia University Press All rights reserved Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data McMenamin, Mark A. The garden of Ediacara : discovering the first complex life / Mark A. S. McMenamin. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-231-10558-4 (cloth) — ISBN 0–231–10559–2 (pbk.) 1. Paleontology—Precambrian. 2. Fossils. I. Title. QE724.M364 1998 560'.171—dc21 97-38073 Casebound editions of Columbia University Press books are printed on permanent and durable acid-free paper. Printed in the United States of America c 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 p 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 For Gene Foley Desert Rat par excellence and to the memory of Professor Gonzalo Vidal This page intentionally left blank Contents Foreword • ix Preface • xiii Acknowledgments • xv 1. Mystery Fossil 1 2. The Sand Menagerie 11 3. Vermiforma 47 4. The Nama Group 61 5. Back to the Garden 121 6. Cloudina 157 7. Ophrydium 167 8. Reunite Rodinia! 173 9. The Mexican Find: Sonora 1995 189 10. The Lost World 213 11. A Family Tree 225 12. Awareness of Ediacara 239 13. Revenge of the Mole Rats 255 Epilogue: Parallel Evolution • 279 Appendix • 283 Index • 285 This page intentionally left blank Foreword Dorion Sagan Virtually as soon as earth’s crust cools enough to be hospitable to life, we find evidence of life on its surface. -

Unusual Arrangement of Bones at Ichthyosaur State Park in Nevada by Mark A

GEOLOGY EVIDENCE FOR A TRIASSIC KRAKEN Unusual Arrangement of Bones at Ichthyosaur State Park in Nevada by Mark A. S. McMenamin Did a giant kraken drag nine huge ichthyosaurs back to its lair in the Triassic era, where their fossil remains are found today? The author of this hypothesis tells why he thinks so. he Triassic Kraken hypothesis, pre- Tsented to the Geological Society of America at its October annual meeting in Minneapolis (McMenamin and McMe- namin 2011), generated an enormous amount of attention on Internet media, immediately after the Society’s press re- lease announcing the discovery. Nine gigantic ichthyosaurs are pre- served in a rock layer belonging to the Shaly Limestone Member of the Luning Formation at the Ichthyosaur State Park in Courtesy of Mark McMenamin Nevada. Geological analysis of this fossil Shonisaurus ichthyosaur vertebral disks at the Berlin-Ichthyosaur State Park in Ne- site had shown it to be a deep water de- vada, arranged in curious linear patterns with almost geometric regularity. The ar- posit (Holger 1992), thus invalidating ranged vertebrae in this Specimen-U resemble the pattern of sucker discs on a cepha- Camp’s (1980) original hypothesis that lopod tentacle, with each vertebra strongly resembling a coleoid sucker. the fossil bed represented an ichthyosaur mass-stranding event. Holger’s (1992) metric patterns, some of which resem- bone arrangement has indeed “never study left unexplained, however, how it ble the sucker arrays on cephalopod been observed at other localities.” came to be that nine giant Shonisaurus tentacles. Seilacher remarked that Jurassic ich- ichthyosaurs sequentially accumulated A YouTube video from the Seattle thyosaur skeletons in Germany, which at virtually the same spot on the Triassic Aquarium, showing a Pacific Octopus may provide analogous examples, occur sea floor. -

The Semantic Web … Sounds Logical!

Rochester Institute of Technology RIT Scholar Works Theses 2004 The Semantic Web … Sounds Logical! Anthony J. Radogna Jr Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.rit.edu/theses Recommended Citation Radogna Jr, Anthony J., "The Semantic Web … Sounds Logical!" (2004). Thesis. Rochester Institute of Technology. Accessed from This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by RIT Scholar Works. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses by an authorized administrator of RIT Scholar Works. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Semantic Web ... Sounds Logical! By Anthony J. Radogna Jr. Rochester Institute of Technology B. Thomas Golisano College of Computing and Information Sciences Master of Science in Information Technology Thesis Approval Form Student Name: Anthony J. Radogna Thesis Title: Semantic Web, The Future is Upon Us Thesis Committee Name Signature Date Prof. Daniel Kennedy Chair Prof. Michael Axelrod Committee Member Prof. Dianne Bills Committee Member I ( Thesis Reproduction Permission Form Rochester Institute of Technology B. Thomas Golisano College of Computing and Information Sciences Master of Science in Information Technology Semantic Web, The Future is Upon Us I, Anthony J. Radogna, hereby grant permission to the Wallace Library of the Rochester Institute of Technology to reproduce my thesis in whole or in part. Any reproduction must not be for commercial use or profit. Date: ~}:)o loy Signature of Author: I I Table of Contents ABSTRACT 2 INTRODUCTION 4 THE INTERNET PAST AND PRESENT 7 THE SEMANTIC WEB EXPLAINED 10 UNIVERSAL RESOURCE IDENTIFIERS 13 EXTENSIBLE MARKUP LANGUAGE 15 RESOURCE DESCRIPTION FRAMEWORK 19 ONTOLOGIES 24 TRUST AND SECURITY ON THE SEMANTIC WEB 28 CONTENT MANAGEMENT 31 GOALS OF THE SEMANTIC WEB 33 CURRENT STATE 35 CONCLUSION 37 REFERENCES 42 APPENDIX 46 The Semantic Web .. -

Introduction to Bioinformatics (Elective) – SBB1609

SCHOOL OF BIO AND CHEMICAL ENGINEERING DEPARTMENT OF BIOTECHNOLOGY Unit 1 – Introduction to Bioinformatics (Elective) – SBB1609 1 I HISTORY OF BIOINFORMATICS Bioinformatics is an interdisciplinary field that develops methods and software tools for understanding biologicaldata. As an interdisciplinary field of science, bioinformatics combines computer science, statistics, mathematics, and engineering to analyze and interpret biological data. Bioinformatics has been used for in silico analyses of biological queries using mathematical and statistical techniques. Bioinformatics derives knowledge from computer analysis of biological data. These can consist of the information stored in the genetic code, but also experimental results from various sources, patient statistics, and scientific literature. Research in bioinformatics includes method development for storage, retrieval, and analysis of the data. Bioinformatics is a rapidly developing branch of biology and is highly interdisciplinary, using techniques and concepts from informatics, statistics, mathematics, chemistry, biochemistry, physics, and linguistics. It has many practical applications in different areas of biology and medicine. Bioinformatics: Research, development, or application of computational tools and approaches for expanding the use of biological, medical, behavioral or health data, including those to acquire, store, organize, archive, analyze, or visualize such data. Computational Biology: The development and application of data-analytical and theoretical methods, mathematical modeling and computational simulation techniques to the study of biological, behavioral, and social systems. "Classical" bioinformatics: "The mathematical, statistical and computing methods that aim to solve biological problems using DNA and amino acid sequences and related information.” The National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI 2001) defines bioinformatics as: "Bioinformatics is the field of science in which biology, computer science, and information technology merge into a single discipline. -

Update 6: Internet Society 20Th Anniversary and Global INET 2012

Update 6: Internet Society 20th Anniversary and Global INET 2012 Presented is the latest update (edited from the previous “Update #6) on the Global INET 2012 and Internet Hall of Fame. Executive Summary By all accounts, Global INET was a great success. Bringing together a broad audience of industry pioneers; policy makers; technologists; business executives; global influencers; ISOC members, chapters and affiliated community; and Internet users, we hosted more than 600 attendees in Geneva, and saw more than 1,300 participate from remote locations. Global INET kicked off with our pre‐conference programs: Global Chapter Workshop, Collaborative Leadership Exchange and the Business Roundtable. These three programs brought key audiences to the event, and created a sense of energy and excitement that lasted through the week. Of key importance to the program was our outstanding line‐up of keynotes, including Dr. Leonard Kleinrock, Jimmy Wales, Francis Gurry, Mitchell Baker and Vint Cerf. The Roundtable discussions at Global INET featured critical topics, and included more than 70 leading experts engaged in active dialogue with both our in‐room and remote audiences. It was truly an opportunity to participate. The evening of Monday 23 April was an important night of celebration and recognition for the countless individuals and organizations that have dedicated time and effort to advancing the availability and vitality of the Internet. Featuring the Internet Society's 20th Anniversary Awards Gala and the induction ceremony for the Internet Hall of Fame, the importance of the evening cannot be understated. The media and press coverage we have already received is a testament to the historic nature of the Internet Hall of Fame. -

Essays from the Edge of Humanitarian Innovation

ESSAYS FROM THE EDGE OF HUMANITARIAN INNOVATION Year in Review 2017 UNHCR Innovation Service From the editors: Year in Review 2017 In the humanitarian and innovation communities, the collective sense of urgency reached new heights this year. Never before has innovation been so important in light of growing needs and fewer resources. Whilst new technologies and platforms continued to advance, we refocused our efforts to the future. Experimentation, research, and refugee voices were central to the new direction. We continued to argue that innovation did not, and does not, equate technology. UNHCR’s Innovation Service was instead focused on behaviour and mindset change - a small nudge team interested less in drones and more in better decision- making. 2017 was also the year that we killed our Innovation Labs and invested in a more holistic approach to innovation, diversity, and collaboration in a way that we hadn’t before. This past year, our programmes and trainings gave UNHCR staff the opportunity to innovate and test new projects and processes across the world. The availability (or lack thereof sometimes) of data continues to have a profound impact on our work at the Innovation Service. If you were to look at the themes found in our year in review, they would be focused on data, storytelling, listening, predicting, and monitoring. In our new publication, we’ve highlighted these themes through stories from the field, stories from refugees, stories on failure, stories on where we’ve been and a look at where we’re going. From research to organisational change, and experiments, take a look back at what UNHCR’s Innovation Service was up to in 2017. -

August 6Th Addresses to Distributed Name Word Document to a Record

Service (DNS), which delegated has a glorious Web interface, the responsibility of assigning and a user can even attach a August 6th addresses to distributed name Word document to a record. servers. In its present form the system Postel’s law is "Be conservative manages roughly $1.3 trillion in Peter Jay in what you do; be liberal in obligations and 340,000 what you accept from others." It contracts. It runs on an IBM Weinberger comes from RFC 761 , where he 2098 model E-10 mainframe, Born: Aug. 6, 1942; summarized desirable that can carry out 398 million Pennsylvania (??) interoperability criteria for the instructions per second. Internet Alfred Aho [Aug 9], Weinberger, There have been several and Brian Kernighan [Jan 1] Postel attended the same high attempts to replace MOCAS, but developed the AWK language school (Van Nuys in Los they’ve floundered due to cost, (he's the “W”) in 1977, which Angeles) as two other Internet complexity, and transition was first distributed in UNIX pioneers, Steve Crocker [Oct 15] planning. Version 7. The acronym is and Vint Cerf [June 23]. pronounced in the same way as the "auk " bird, which also acts The WWW Virtual as the language's emblem. In 1985 they extended the Library language, most significantly by adding user-defined functions. Aug. 6, 1991 This version is sometimes called “new awk” or nawk. The WWW Virtual Library ( http://vlib.org/) is the When Weinberger was oldest Web directory, able to promoted to be the head of trace its venerable heritage back Computer Science Research at to Tim Berners-Lee’s [June 8] Bell Labs [Jan 1], his picture was WWW overview page [next merged with the AT&T “death entry] at CERN. -

Tomorrow's Standard

Today's Perfect - Tomorrow's Standard The Role of Consumers and The Limits of Policy in Recycling Jonas Kågström Faculty of Natural Resources and Agricultural Sciences Department of Economics Uppsala Doctoral Thesis Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences Uppsala 2011 Acta Universitatis agriculturae Sueciae 2011:33 Cover: Just as the traditional recycling symbol of three arrows giving chase to each other form a sort of Ouroboros , so too does this illustration from issue nr 14:1896 of the Jugend Magazine by Otto Eckmann (1865 – 1902) represent , to me, the ever cyclic and dynamic nature of the interplay between policy , implementation and citizens. ISSN 1652-6880 ISBN 978-91-576-7568-2 © 2011 Jonas Kågström, Uppsala Print: SLU Service/Repro, Uppsala 2011 2 Today's Perfect - Tomorrow's Standard, The Role of Consumers and The Limits of Policy in Recycling Abstract In this study the mechanisms influencing recycling rates around the system maximum are deliberated. On the one hand, Policies, System design and how Citizens understand the two aforementioned are pitted against each other. This is done in a setting where individual rewards from action are in turn set against the values of the community and the compliance measures/social marketing of recycling companies and policy makers. This is the dynamic setting of this dissertation. In the past much research into recycling has been focused on how to get recycling started. Sweden is in a bit of a different position with recycling levels often being very high in an international comparison. This means other challenges face citizens and policy makers alike. The determinants influencing recycling rates are studied and compared to contemporary research. -

List of Internet Pioneers

List of Internet pioneers Instead of a single "inventor", the Internet was developed by many people over many years. The following are some Internet pioneers who contributed to its early development. These include early theoretical foundations, specifying original protocols, and expansion beyond a research tool to wide deployment. The pioneers Contents Claude Shannon The pioneers Claude Shannon Claude Shannon (1916–2001) called the "father of modern information Vannevar Bush theory", published "A Mathematical Theory of Communication" in J. C. R. Licklider 1948. His paper gave a formal way of studying communication channels. It established fundamental limits on the efficiency of Paul Baran communication over noisy channels, and presented the challenge of Donald Davies finding families of codes to achieve capacity.[1] Charles M. Herzfeld Bob Taylor Vannevar Bush Larry Roberts Leonard Kleinrock Vannevar Bush (1890–1974) helped to establish a partnership between Bob Kahn U.S. military, university research, and independent think tanks. He was Douglas Engelbart appointed Chairman of the National Defense Research Committee in Elizabeth Feinler 1940 by President Franklin D. Roosevelt, appointed Director of the Louis Pouzin Office of Scientific Research and Development in 1941, and from 1946 John Klensin to 1947, he served as chairman of the Joint Research and Development Vint Cerf Board. Out of this would come DARPA, which in turn would lead to the ARPANET Project.[2] His July 1945 Atlantic Monthly article "As We Yogen Dalal May Think" proposed Memex, a theoretical proto-hypertext computer Peter Kirstein system in which an individual compresses and stores all of their books, Steve Crocker records, and communications, which is then mechanized so that it may Jon Postel [3] be consulted with exceeding speed and flexibility. -

Can We Understand Evolution Without Symbiogenesis?

Can We Understand Evolution Without Symbiogenesis? Francisco Carrapiço …symbiosis is more than a mere casual and isolated biological phenomenon: it is in reality the most fundamental and universal order or law of life. Hermann Reinheimer (1915) Abstract This work is a contribution to the literature and knowledge on evolu- tion that takes into account the biological data obtained on symbiosis and sym- biogenesis. Evolution is traditionally considered a gradual process essentially consisting of natural selection, conducted on minimal phenotypical variations that are the result of mutations and genetic recombinations to form new spe- cies. However, the biological world presents and involves symbiotic associations between different organisms to form consortia, a new structural life dimension and a symbiont-induced speciation. The acknowledgment of this reality implies a new understanding of the natural world, in which symbiogenesis plays an important role as an evolutive mechanism. Within this understanding, symbiosis is the key to the acquisition of new genomes and new metabolic capacities, driving living forms’ evolution and the establishment of biodiversity and complexity on Earth. This chapter provides information on some of the key figures and their major works on symbiosis and symbiogenesis and reinforces the importance of these concepts in our understanding of the natural world and the role they play in the establishing of the evolutionary complexity of living systems. In this context, the concept of the symbiogenic superorganism is also discussed. Keywords Evolution · Symbiogenesis · Symbiosis · Symbiogenic superorgan- ism · New paradigm F. Carrapiço (*) Centre for Ecology Evolution and Environmental Change (CE3C); Centre for Philosophy of Science, Department of Plant Biology, Faculty of science, University of Lisbon, Lisbon, Portugal e-mail: [email protected] © Springer International Publishing Switzerland 2015 81 N. -

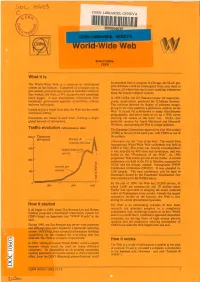

What It Is How It Started How It Works

Robert Cailliau CERN What it is be consulted from a computer in Chicago, the SLAC pre The World-Wide Web is a client-server information print database could be interrogated from your desk in system on the Internet. Conceived as a unique way to Geneva, all without having to know anything whatsoever give particle physicists easy access to their data wherever about the remote computer systems. they worked, the Web, or W3, has grown into something much bigger. It now disseminates information from In 1993 NCSA, the US National Center for Supercom businesses, government agencies, universities, schools puting Applications, produced the X-Mosaic browser. and even individuals. This software allowed the display of coloured images, giving to the Unix platform a glamorous window on the Instead of just a single local disk, the Web has the whole Web. It stirred the exhibitionist in many Unix/Internet world as its library. programmers, and drove them to set up a Web server Documents are linked to each other, forming a single showing off scenes of the local site. NCSA also global network of information. produced versions for Apple Macintosh and Microsoft Windows, thus opening the Web to a large audience. Traffic evolution (NFS backbone, USA) The European Commission approved its first Web project (WISE) at the end of the same year, with CERN as one of 2oook r Characters the partners. I per second Prodigy& - America On Line 1994 reaiiy was rhe "Year of the -W"eb". Tne worid's First International World-Wide Web conference was held at CERN in May.