[Speech to Oregon Trail Interpretive Center Siting Committee, Ca

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Burnt River Water Temperature Study Commitee Final Report

BURNT RIVER WATER TEMPERATURE STUDY STEERING COMMITTEE FINAL REPORT Prepared for the Burnt River Steering Committee by David Duncan and Associates Boise, Idaho April 2002 TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................................ 1 Study Description ...................................................................................................................... 1 Study Area ................................................................................................................................. 1 OBJECTIVE 1: FACTORS CONTRIBUTING TO STREAM TEMPERATURES ...................... 2 Baseline Temperatures............................................................................................................... 2 Upper Watersheds .............................................................................................................. 2 Lower Watersheds .............................................................................................................. 2 How Does Heat Energy Enter and Leave a Stream? ................................................................. 3 Radiation.................................................................................................................................... 5 Atmospheric Radiation....................................................................................................... 7 Radiation from Riparian Vegetation and Topographic Features....................................... -

Baker County Community Sensitivity and Resilience

Baker County Community Sensitivity and Resilience This section documents the community’s sensitivity factors, or those community assets and characteristics that may be impacted by natural hazards, (e.g., special populations, economic factors, and historic and cultural resources). It also identifies the community’s resilience factors, or the community’s ability to manage risk and adapt to hazard event impacts (e.g., governmental structure, agency missions and directives, and plans, policies, and programs). The information in this section represents a snapshot in time of the current sensitivity and resilience factors in the community when the plan was developed. The information documented below, along with the findings of the risk assessment, should be used as the local level rationale for the risk reduction actions identified in Section 6 – Mission, Goals, and Action Items. The identification of actions that reduce a community’s sensitivity and increase its resilience assists in reducing the community’s overall risk, or the area of overlap in Figure G.1 below. Figure G.1 Understanding Risk Source: Oregon Natural Hazards Workgroup, 2006. Northeast Oregon Natural Hazard Mitigation Plan Page G-1 Community Sensitivity Factors The following table documents the key community sensitivity factors in Baker County. Population • Baker County has eight distinct geographic populations, as well as eight unincorporated communities. Incorporated cities are: Baker City, Greenhorn, Haines, Halfway, Huntington, Richland, Sumpter, and Unity. Unincorporated communities include: Durkee, Hereford, Pinetown, McEwen, Keating, Sparta, New Bridge, and Oxbow. Communities are geographically dispersed with little communication or interconnection. If communities need to be warned of an event, or require disaster assistance, distance and dispersal will be communication barriers. -

MINING in BAKER COUNTY, 1861 to 1959* by Norman S

Vol.21, No.3 THE ORE.- BIN 21 March 1959 Portland, Oregon STATE OF OREGON DEPARTMENT OF GEOLOGY AND MINERAL INDUSTRIES Head Office: 1069 State Office Bldg., Portland I, Oregon Telephone: CApitol 6-2161, Ext. 488 Field Offices 2033 First Street 239 S. E. "H"Street Baker Grants Pass *************************** MINING IN BAKER COUNTY, 1861 to 1959* By Norman S. Wagner** Introduction Baker County mining began with the discovery of gold in 'Griffin Gulch in 1861. This and the develop ment which followed at Auburn represent gold mining at its historic best. Since 1861, much water has flowed down the sluice boxes with respect to mineral resource development within the county. As a result, the dis covery story is left for historians to tell, and the following paragraphs are devoted to the high points of the many kinds of mining endeavors that occurred in Baker County between 1861 and 1959. Hydraulic and sluicing operations All of the earlier placer operations have one thing in common with Griffin Gulch and Auburn. This is that they were carried out by means of ground sluicing and hydraul icking, using generous amounts of hand labor. These means of handl ing placer ground continued in exclusive use throughout the first forty years of Baker County mining history. It wasn't until the present century that the more familiar bucket-line dredges and other kinds of mechanized digging and washing plants made their appearance. Even yet the old methods are still employed on a small scale in circumstances where ground conditions permit. The Rye Valley placers on Dixie Creek represent a notable example of an early discovery made shortly after 1862. -

Bull Trout Recovery Plan App Introduction

Chapter 13 - Hells Canyon INTRODUCTION Recovery Unit Designation The Hells Canyon Complex Recovery Unit is 1 of 22 recovery units designated for bull trout in the Columbia River basin (Figure 1). The Hells Canyon Complex Recovery Unit includes basins in Idaho and Oregon, draining into the Snake River and its associated reservoirs from below the confluence of the Weiser River downstream to Hells Canyon Dam. This recovery unit contains three Snake River reservoirs, Hells Canyon, Oxbow, and Brownlee. Major watersheds are the Pine Creek, Powder River, and Burnt River drainages in Oregon, and the Indian Creek and Wildhorse River drainages in Idaho. Inclusion of bull trout in the Oregon tributaries (i.e., Pine Creek and Powder River) in one recovery unit is based in part on a single gene conservation unit (i.e., roughly the major drainages in Oregon inhabited by bull trout) recognized by the Figure 1. Bull trout recovery units in the United States. The Hells Canyon Complex Recovery Unit is highlighted. 1 Chapter 13 - Hells Canyon Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife (Kostow 1995), which is supported by the genetic analysis conducted by Spruell and Allendorf (1997). Although the genetic composition of bull trout in the two tributaries in Idaho has not been extensively studied, the streams were included in the recovery unit due to their close proximity to the tributaries in Oregon containing bull trout, and the likelihood that bull trout from all tributaries were able to interact historically. Administratively, the Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife established a working group to develop bull trout conservation strategies in Pine Creek, and the streams in Idaho were included in the Hells Canyon Key Watersheds in the Idaho Bull Trout Conservation Plan (Grunder 1999). -

North Burnt River Fuel & Forest Health Project

NORTH BURNT RIVER FUEL & FOREST HEALTH PROJECT Environmental Assessment # DOI-BLM-OR-V050-2009-015 Introduction: The Vale District Bureau of Land Management (BLM), Baker Resource Area proposes the treatment of approximately 700 acres of forested BLM-administered lands within the Ebell Creek, Alder Creek, Hill Creek and Deer Creek drainages. The legal description of the project area is as follows: T. 11 S., R. 41 E., Section 7: NW ¼ NE ¼, E ½ NE ¼; Section 8: W ½ SW ¼, SE ¼ SW ¼; Section 11: W ½ NW ¼; Section 14: NW ¼ NW ¼, SE ¼ SW ¼; Section 23: N ½ NE ¼ SE ¼ NE ¼; Section 24: S ½ NW ¼, S ½ NE ¼ and T. 11 S., R. 42 E., Section 17 N ½ SW ¼; Section 18 NE ¼ SE ¼; Section 19 S ½ NW ¼. The project objective is to apply a three-tiered approach (e.g., a combination of Commercial Thinning (CT), Precommercial Thinning (PCT), and Prescribed Burning) to reduce fire fuels and restoring forest health, which includes the reduction of ground, ladder, and crown fuels. Proposed Action: The Baker Field Office of the Vale District, BLM proposes to remove fuels and improve forest health in the North Burnt River Area on lands administered by the BLM. Type of Statement: Environmental Assessment (EA) Agency: Bureau of Land Management, Department of Interior For further information: Bureau of Land Management Baker Field Office 3285 11th St. Baker City, OR 97814 (541) 523-1339 E-Mail: [email protected] Contents Finding of No Significant Impact (FONSI) Introduction Chapter 1.0 Purpose of and Need for Action 1.1 Conformance with Existing Land Use Plans 1.1.a -

Or Wilderness Protection in the Blue Mountain Ecoregion Have Been Identified by the Nature Conservancy As Vital to Protect Biodiversity in the Area

172 OREGON WILD Neither Cascades nor Rockies, but With Attributes of Both Blue Mountains Ecoregion xtending from Oregon’s East Cascades Slopes and Foothills to the from 30 to 130 days depending on elevation. The forests are home to Rocky Mountain intersection of Oregon, Idaho and Washington, the 15.3 million acres elk, mule deer, black bear, cougar, bobcat, coyote, beaver, marten, raccoon, fisher, of the Blue Mountains Ecoregion in Oregon are a conglomeration of pileated woodpecker, golden eagle, chickadee and nuthatch, as well as various species Emountain ranges, broad plateaus, sparse valleys, spectacular river canyons of hawks, woodpeckers, owls and songbirds. Wolves, long absent from Oregon, are and deep gorges. The highest point is the Matterhorn that rises to 9,832 making their return to the state in this ecoregion. Individuals from packs reintroduced feet in the Wallowa Mountains. The ecoregion extends into southeastern Washington in nearby Idaho are dispersing into Oregon. Fish species include bull and rainbow and west central Idaho. trout, along with numerous stocks of Pacific salmon species. Most of the mountain ranges in the Blue Mountains Ecoregion are volcanic. The Depending on precipitation, aspect, soil type, elevation, fire history and other Crooked River separates the Maury Mountains from the Ochoco Mountains, which are factors, one generally finds various combinations of Douglas-fir, ponderosa pine, lodge- separated from the Aldrich Mountains by the South Fork John Day River. The Aldrich pole, western larch, juniper and Engelmann spruce throughout the Blue Mountains. Mountains are separated from the Strawberry Mountain Range by Canyon Creek. Beginning approximately at the Lower Deschutes River and rising eastward, the These ranges generally run east-west. -

Detailed Descriptions of Mining Districts

CHAPTER VI. DE~l'AILED DESCRIPTIONS OF MINING DISTIUCTS (CONTINUED). VIRTUE DISTRICT. GENERAL l!~EATURES. The Virtue mining district, one of the ,oldest in eastern Oregon, is situated about 7 miles east of !Baker City, and extends for about 12 miles in a northwesterly direction, the width varying between 3 and 6 miles. It covers a region of low arid hills rising in the gi·eat bend of Powder River, and may be considered as the no.rthwesterly continua tion of the Lookout complex. The elevations range from 3,400 to 5,000 feet. The hills rise rather abruptly from Baker Valley and slope gently eastward toward the lower Powder River Valley. Most of the drainage is toward the latter. A rather remarkable feature within the hills is Virtue Flat, a desolate, sage-covered depression extending 8 miles east and west by 2 miles north and south. The water supply is very scant, the only :flowing stream being Ruckles Creek, practically outside of the district. GEOLOGY. The predominating roek of ,the northern part of the district is a lighter or darker greenish-gray dioritic rock of granular texture, which nearly always bears evidence of Rtrong crushing, but rarely of schis tosity. Frequently the rock is a veritable breccia, the diff~rent frag ments being eemented by seams of feldspar or zoisite. The feldspars are largely converted into a :flinty white mass resembling saussurite, and the hornblende seems uralitic. The microscope shows, in fact, that the rock is rather a saussuritic uralite-gabbro than a true diorite. This rock decomposes to a very light-colored dusty soil. -

Eastern Oregon Before the Oregon Trail: the First White Men in Oregon* by Gary Dielman

Eastern Oregon before the Oregon Trail: The First White men in Oregon* by Gary Dielman Last time I spoke to you, I brought lots of photos from the McCord Collection. This time I have no photos, but instead will paint a mental picture of this area before white men arrived. First we must use an eraser on the present picture. Erase the towns, the farms houses and outbuildings, the asphalt and dirt roads, and with them all the vehicles and every other modern convenience. And let's not forget to take out all the dams, so that the rivers once again run wild and salmon again spawn in the upper reaches of Powder River above Sumpter. Now that we have erased all evidence of modern civilization, let's look at our new picture of Baker Valley beginning in the foothills of the northwest corner on Pilcher Creek where, until a few moments ago, there was a dam and reservoir. Now it is restored to a large oblong grass-covered meadow with a little creek flowing thru it. It's summer time and although down in the valley it is hot, up here in the meadow it is cooler and the water runs fresher and there are camas roots in the meadow and huckleberries to gather on the surrounding slopes. And of course the deer and elk are nearby. That's probably why there is a small band of Indians camped here and why they have been coming here to spend the warm part of the year for thousands and thousands of years. -

Ground-Water Reconnaissance in the Burnt River Valley Area, Oregon

Ground-Water Reconnaissance in the Burnt River Valley Area, Oregon GEOLOGICAL SURVEY WATER-SUPPLY PAPER 1839-1 Prepared in cooperation with the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation and the Oregon State Engineer Ground-Water Reconnaissance in the Burnt River Valley Area, Oregon By DON PRICE CONTRIBUTIONS TO THE HYDROLOGY OF THE UNITED STATES GEOLOGICAL SURVEY WATER-SUPPLY PAPER 1839-1 Prepared in cooperation with the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation and the Oregon State Engineer UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE, WASHINGTON : 1967 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR STEWART L. UDALL, Secretary GEOLOGICAL SURVEY William T. Pecora, Director For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Washington, D.G. 20402 CONTENTS Page Abstract-. ___________ II Introduction..____________ ________________________________________ 2 Purpose and scope of the investigation_______'____________________ 2 Location and extent of the area_________________________________ 2 Previous investigations___________________________ 2 Acknowledgments. ___________________________ 4 Well-numbering system__-_____________________________ 4 Geography_____________________________________________ 4 Climate. ___________________________________ ____ 4 Topography and drainage._______________________ 8 Culture and industry_______________________________________ 10 Geologic setting _ 10 Ground water____________________________________ 10 General features of occurrence_________________________-__-____- 10 Ground-water potential of selected rock units ___________________ -

C:\Bull Trout Final\WPD Final\Chapter 14 Malheur Recovery Unit, Oregon

Chapter: 14 State(s): Oregon Recovery Unit Name: Malheur Recovery Unit Region 1 U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Portland, Oregon DISCLAIMER Recovery plans delineate reasonable actions that are believed necessary to recover and protect listed species. Plans are prepared by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, and in this case, with the assistance of recovery unit teams, State and Tribal agencies, and others. Objectives will be attained and any necessary funds made available subject to budgetary and other constraints affecting the parties involved, as well as the need to address other priorities. Recovery plans do not necessarily represent the views nor the official positions or approval of any individuals or agencies involved in plan formulation, other than the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. Recovery plans represent the official position of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service only after they have been signed by the Director or Regional Director as approved. Approved recovery plans are subject to modification as dictated by new findings, changes in species status, and the completion of recovery tasks. Literature Citation: U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 2002. Chapter 14, Malheur Recovery Unit, Oregon. 71 p. In: U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. Bull Trout (Salvelinus confluentus) Draft Recovery Plan. Portland, Oregon. ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Members of the Malheur Recovery Unit Team who assisted in the preparation of this chapter include: Wayne Bowers, Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife Jason Fenton, Burns Paiute Tribe Tom Friedrichsen, U. S. Forest Service, Burns Ranger District Dan Gonzalez, Burns Paiute Tribe Gina Lampman, Bureau of Land Management Sam Lohr, U.S. -

DOGAMI GMS-13, Geologic Map of Huntington and Part of Olds Ferry

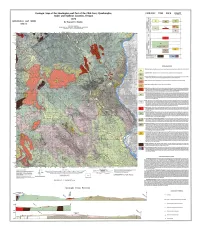

Geologic Map of the Huntington and Part of the Olds Ferry Quadrangles, GEOLOGIC TIME ROCK CHART Age in Mili<ns of V,or, Baker and Malheur Counties, Oregon 1979 ~., z i •.,.•4"'.,.A",, ~ GEOLOGICAL MAP SERIES Qal 4\ O,AQts .. \ <.,) i\'.i$ij, : '.'?, . • ,0 4 • A "' By Howard C. Brooks "' "'····'·• .. ..·: .; .. : .• .....'.' . ·., .."., ] GMS 13 -0 :, ' N • 0 ,., ST A T E O F ORE GON z " • DEPARTMENT O F GEOLOGY AND MINER AL INDUST R IES w .,'" f Tpb DON ALD A. H U LL, S T A T E G EOLOGIST <.,) " Tst -Ii: ., :tt,·1~::tii n.s .. ~ )"'-ff; .' .i~, " ,,o/'.!?~,/.l<."' •.,•;,,'ii, .. " "' "u • ''" -u ~, <.,) "'< • •l 0 -N .,"' • 0 " I {/l) .l w l.G ,.,1t .;., .,, 190-5 ., ,, ., n,. r,, . .,.., . ,. :,: u ~· • 1"· .,,-,.-1 - • "'., k ..iii "' MIE§OZOXC & PALEOZOIC 1• • ~!11 - '" EXPLANATION EJ Alluvium : Mainly oolky fill and recent stream-channel deposits consisting ofunconsolidated silt, sand, and grovel Lands lide debris: Bedrock failure on oversteepened sicpes; typified by hummocky topography Terrace and fan deposits : Unconsolidated, generally non bedded and poorly sorted deposits of grovel, cobbks, boulders, clay, silt, and sand occurring topographically above the present {wad plains Basalt : Mostly thin, gently dipping ff,ows af olivine·bearing groy to black basalt and basaltic an desire S ma ll mafic volcanic centers : Probably the source of Toh flows Basalt : Mostly basalt ff,ows. Locally includes water-laid bru;altic tu(( and breccia, mud.flow ckposits, and tuffnceous sedimentary rocks. Pl.aty flow structure is acomrrwnfeature ofmost ofthe basalt. Some ofthe basalt, especially in secs. 34and35, T.12 S., R. 44E.,andsecs.2and3, T.13 S.,R. -

Mineral Resources of Oregon

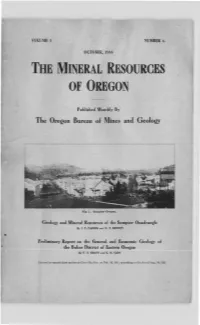

VOLUME I NUMBER 6 OCTOBER, 1914 THE MINERAL RESOURCES OF OREGON Pul>lished Monthly By The Oregon Bureau of Mines and Geology Fig. S. Sumpter Oregon. Geolo"y and Mineral Resources of the Sumpter Ouadran"le By J. T. PARDBB and D. F. BBWBTT • Preliminary Report on the General and Economic Geolo1,1y of the Baker District of Eastern Orel,1on By U. S. GRANT and G. B. CADI Entered a• second cln!s mntter at Corvnllis, Ore. on Feb. 10, 1914, according to the Act of Aug. 24, 1912 20' 118°00' . _ "....... R. 3~~· .. 45°00 ,\'7\1,"- · ' ' . : ,/1,~ J\1 ,... __ ,, 1\ ~ .... , . ··.· .. ·:·.·.··· · _. ::... :·1 T.6.5 . LE.GE.ND T./.5. ROCK FORMATIONS ~> ......>-o:x: 0:: CX:z . <t:cr: . -w [2].. LLJ:::>~~ Surficial Deposits ..... 0 Recent and Pleistocene Alluvium, and UJO Pleistocene qlacial drift and Quat-ernary ~:z and late Tertiary(?) qravels. -I<( Chiefly andesitic and basaltic lavas ~ includinq related• tuffs and breccias. <t T.8.S. (~hiefly older than· the lake beds. but 1- onpartyoun. a::: I.LJ 1- 50' Lake beds w \ \ r ,-{ I 1 ,-,.~/,-/,, ~u 1." ,,- ,,-,:. ,,~ .....10 V\ /- ' ,... ~N - ' \ /\ /' ,_ C(JQ ' ' /,-I', I <:((J) Chiefly qranodiori'te C:Ow bvt includes ~losely relaTed ~~ 'qranitic rocks~ a. T.9.S. 0 z ~ <(()- Limestone .. uo oo-N owNU> Wl: D _J Argillite series, ~ includes iqneous rocks older than 'the granodiorite .. T.IO.S. 40' II [2J Quartz mine D Placer m1ne c:J Quarry CSJ Downthrow side' of FaulT block ~·: T.l2 \ .~ ,.. '..!!! ~x c r < < < < < < r < A r r c c rr r C,• .(£:£{! ?<' < c r t]l¥ ty < r < r r ere ?1ff1£ff rc r r < crr<r /&l\.:Y''\"))"""A:Y'" :s"'"'...,..:r t;..(£..!£ ( r r err X?\"\l}')''='-"\'\W:·:r.