A Modernist Study of the Death Certificate and 'Comala'

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Vaikom Muhammad Basheer and Indian Literature Author(S): K

Sahitya Akademi Vaikom Muhammad Basheer and Indian Literature Author(s): K. Satchidanandan Source: Indian Literature, Vol. 53, No. 1 (249) (January/February 2009), pp. 57-78 Published by: Sahitya Akademi Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/23348483 Accessed: 25-03-2020 10:34 UTC JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at https://about.jstor.org/terms Sahitya Akademi is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Indian Literature This content downloaded from 103.50.151.143 on Wed, 25 Mar 2020 10:34:33 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms A BIRTH CENTENARY TRIBUTE Vaikom Muhammad Basheer and Indian Literature K. Satchidanandan I Vaikom like Muhammadto call the democratic Basheer tradition (1908-1994) in Indian belongsliterature, firmly a living tradition to what I that can be traced back to the Indian tribal lore including the Vedas and the folktales and fables collected in Somdeva's Panchatantra and Kathasaritsagar, Gunadhya's Brihatkatha, Kshemendra's Brihatkathamanjari, the Vasudeva Hindi and the Jatakas. This tradition was further enriched by the epics, especially Ramayana and Mahabharata that combined several legends from the oral tradition and are found in hundreds of oral, performed and written versions across the nation that interpret the tales from different perspectives of class, race and gender and with different implications testifying to the richness and diversity of Indian popular imagination and continue to produce new textual versions, including dalit, feminist and other radical interpretations and adaptations even today. -

Love and Marriage Across Communal Barriers: a Note on Hindu-Muslim Relationship in Three Malayalam Novels

Love and Marriage Across Communal Barriers: A Note on Hindu-Muslim Relationship in Three Malayalam Novels K. AYYAPPA PANIKER If marriages were made in heaven, the humans would not have much work to do in this world. But fornmately or unfortunately marriages continue to be a matter of grave concern not only for individuals before, during, and/ or after matrimony, but also for social and religious groups. Marriages do create problems, but many look upon them as capable of solving problems too. To the poet's saying about the course of true love, we might add that there are forces that do not allow the smooth running of the course of true love. Yet those who believe in love as a panacea for all personal and social ills recommend it as a sure means of achieving social and religious integration across caste and communal barriers. In a poem written against the backdrop of the 1921 Moplah Rebellion in Malabar, the Malayalam poet Kumaran Asan presents a futuristic Brahmin-Chandala or Nambudiri-Pulaya marriage. To him this was advaita in practice, although in that poem this vision of unity is not extended to the Muslims. In Malayalam fi ction, however, the theme of love and marriage between Hindus and Muslims keeps recurring, although portrayals of the successful working of inter-communal marriages are very rare. This article tries to focus on three novels in Malayalam in which this theme of Hindu-Muslim relationship is presented either as the pivotal or as a minor concern. In all the three cases love flourishes, but marriage is forestalled by unfavourable circumstances. -

Representation of Transgender Identities in Malayalam Literature

International Journal of Humanities and Social Science Invention (IJHSSI) ISSN (Online): 2319 – 7722, ISSN (Print): 2319 – 7714 www.ijhssi.org ||Volume 10 Issue 2 Ser. I || February 2021 || PP 40-42 Trapped Bodies: Representation of Transgender Identities in Malayalam Literature Lalini M. ABSTRACT The transgender community is a highly marginalised and vulnerable one and is seriously lagging behind on human development. The early society of Kerala will not accept a third gender. In the world literature transgenders became a significant branch of study has occurred .This article mainly focused on how Malayalam short stories presents transgender in the world of literature.. KEY WORDS: Transgender, Malayalam Literature, Gender roles,Identities --------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- Date of Submission: 25-01-2021 Date of Acceptance: 09-02-2021 --------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- I. INTRODUCTION Human society is a complex organisation of human role relationships. The implication of such a structural conception is that the human beings act and interact with each other in accordance with the role they play. Their role performance in relation to each other is further conditioned by the status they occupy. The most basic criterion of defining status and a corresponding role for any individual in any society has been sex. Accordingly, men have been assigned certain specific type of roles to perform and women certain other. Sometimes, the society expects both men and women to discharge some roles jointly or interchangeably .Such and many other type similar situations present a general case of role performance and, therefore do not become an object of curiosity for people in society. This way, the individuals continue to act and interact with each other in accordance with the patterned and institutionalised frame work of role relationship in the society. -

List of Books 2018 for the Publishers.Xlsx

LIST I LIST OF STATE BARE ACTS TOTAL STATE BARE ACTS 2018 PRICE (in EDITION SL.No. Rupees) COPIES AUTHOR/ REQUIRED PRICE FOR EDN / YEAR PUBLISHER EACH COPY APPROXIMATE K.G. 1 Abkari Laws in Kerala Rajamohan/Ar latest 898 5 4490 avind Menon Govt. 2 Account Code I Kerala latest 160 10 1600 Publication Govt. 3 Account Code II Kerala latest 160 10 1600 Publication Suvarna 4 Advocates Act latest 790 1 790 Publication Advocate's Welfare Fund Act George 5 & Rules a/w Advocate's Fees latest 120 3 360 Johnson Rules-Kerala Arbitration and Conciliation 6 Rules (if amendment of 2016 LBC latest 80 5 400 incorporated) Bhoo Niyamangal Adv. P. 7 latest 1500 1 1500 (malayalam)-Kerala Sanjayan 2nd 8 Biodiversity Laws & Practice LBC 795 1 795 2016 9 Chit Funds-Law relating to LBC 2017 295 3 885 Chitty/Kuri in Kerala-Laws 10 N Y Venkit 2012 160 1 160 on Christian laws in Kerala Santhosh 11 2007 520 1 520 Manual of Kumar S Civil & Criminal Laws in 12 LBC 2011 250 1 250 Practice-A Bunch of Civil Courts, Gram Swamy Law 13 Nyayalayas & Evening 2017 90 2 180 House Courts -Law relating to Civil Courts, Grama George 14 Nyayalaya & Evening latest 130 3 390 Johnson Courts-Law relating to 1 LIST I LIST OF STATE BARE ACTS TOTAL STATE BARE ACTS 2018 PRICE (in EDITION SL.No. Rupees) COPIES AUTHOR/ REQUIRED PRICE FOR EDN / YEAR PUBLISHER EACH COPY APPROXIMATE Civil Drafting and Pleadings 15 With Model / Sample Forms LBC 2016 660 1 660 (6th Edn. -

Masculinity and the Structuring of the Public Domain in Kerala: a History of the Contemporary

MASCULINITY AND THE STRUCTURING OF THE PUBLIC DOMAIN IN KERALA: A HISTORY OF THE CONTEMPORARY Ph. D. Thesis submitted to MANIPAL ACADEMY OF HIGHER EDUCATION (MAHE – Deemed University) RATHEESH RADHAKRISHNAN CENTRE FOR THE STUDY OF CULTURE AND SOCIETY (Affiliated to MAHE- Deemed University) BANGALORE- 560011 JULY 2006 To my parents KM Rajalakshmy and M Radhakrishnan For the spirit of reason and freedom I was introduced to… This work is dedicated…. The object was to learn to what extent the effort to think one’s own history can free thought from what it silently thinks, so enable it to think differently. Michel Foucault. 1985/1990. The Use of Pleasure: The History of Sexuality Vol. II, trans. Robert Hurley. New York: Vintage: 9. … in order to problematise our inherited categories and perspectives on gender meanings, might not men’s experiences of gender – in relation to themselves, their bodies, to socially constructed representations, and to others (men and women) – be a potentially subversive way to begin? […]. Of course the risks are very high, namely, of being misunderstood both by the common sense of the dominant order and by a politically correct feminism. But, then, welcome to the margins! Mary E. John. 2002. “Responses”. From the Margins (February 2002): 247. The peacock has his plumes The cock his comb The lion his mane And the man his moustache. Tell me O Evolution! Is masculinity Only clothes and ornaments That in time becomes the body? PN Gopikrishnan. 2003. “Parayu Parinaamame!” (Tell me O Evolution!). Reprinted in Madiyanmarude Manifesto (Manifesto of the Lazy, 2006). Thrissur: Current Books: 78. -

Colonial Rule in Kerala and the Development of Malayalam Novels: Special Reference to the Early Malayalam Novels

RESEARCH REVIEW International Journal of Multidisciplinary 2021; 6(2):01-03 Research Paper ISSN: 2455-3085 (Online) https://doi.org/10.31305/rrijm.2021.v06.i02.001 Double Blind Peer Reviewed/Refereed Journal https://www.rrjournals.com/ Colonial Rule in Kerala and the Development of Malayalam Novels: Special Reference to the Early Malayalam Novels *Ramdas V H Research Scholar, Comparative Literature and Linguistics, Sree Sankaracharya University of Sanskrit, Kalady ABSTRACT Article Publication Malayalam literature has a predominant position among other literatures. From the Published Online: 14-Feb-2021 ‘Pattu’ moments it had undergone so many movements and theories to transform to the present style. The history of Malayalam literature witnessed some important Author's Correspondence changes and movements in the history. That means from the beginning to the present Ramdas V H situation, the literary works and literary movements and its changes helped the development of Malayalam literature. It is difficult to estimate the development Research Scholar, Comparative Literature periods of Malayalam literature. Because South Indian languages like Tamil, and Linguistics, Sree Sankaracharya Kannada, etc. gave their own contributions to the development of Malayalam University of Sanskrit, Kalady literature. Especially Tamil literature gave more important contributions to the Asst.Professor, Dept. of English development of Malayalam literature. The English education was another milestone Ilahia College of Arts and Science of the development of Malayalam literature. The establishment of printing presses, ramuvh[at]gmail.com the education minutes of Lord Macaulay, etc. helped the development process. People with the influence of English language and literature, began to produce a new style of writing in Malayalam literature. -

MTS EXAMINATION 2015 -16 Class : X QUESTION PAPER 10 Score : 400 Register No : Time : 2 Hrs

MTS EXAMINATION 2015 -16 Class : X QUESTION PAPER 10 Score : 400 Register No : Time : 2 hrs General Instructions 1. Candidates are supplied with an OMR Answer Sheet. 2. Answer the questions in the OMR Sheet by shading the appropriate bubble. 3. Shade the bubbles with black ball point pen. 4. Each question carries four marks. One mark will be deducted for each wrong answer. 5. Use the space provided in the last page for rough work. Read the passage and answer the questions from 1 to 4. For many years, the continent Africa remained unexplored and unknown. The main reason was the inaccessibility to its interior region due to dense forests, wild life, savage tribals, de- serts and barren solid hills. Many people who tried to explore the land could not survive the dangers. David Livingstone is among those brave few who not only explored part of Africa but also lived among the tribals bringing them near to Social Milieu. While others explored with the idea of expanding their respective empires. Livingstone did so to explore its vast and mysteri- ous hinterland, rivers and lakes. He was primarily a religious man and a medical practitioner who tried to help mankind with it. Livingstone was born in Scotland and was educated to become a doctor and priest. His exploration started at the beginning of the year 1852. He ex- plored an unknown river in Western Luanda. However, he was reduced to a skeleton during four years of travelling. By this time, he had become famous and when he returned to England for convalescing, entire London along with Queen Victoria turned to welcome him. -

Library Stock.Pdf

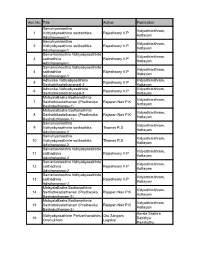

Acc.No. Title Author Publication Samuhyashasthra Vidyarthimithram, 1 Vidhyabyasathinte saithadhika Rajeshwary V.P Kottayam Adisthanangal-1 Samuhyashasthra Vidyarthimithram, 2 Vidhyabyasathinte saithadhika Rajeshwary V.P Kottayam Adisthanangal-1 Samaniashasthra Vidhyabyasathinte Vidyarthimithram, 3 saithadhika Rajeshwary V.P Kottayam Adisthanangal-1 Samaniashasthra Vidhyabyasathinte Vidyarthimithram, 4 saithadhika Rajeshwary V.P Kottayam Adisthanangal-1 Adhunika Vidhyabyasathinte Vidyarthimithram, 5 Rajeshwary V.P Saithathikadisthanangal-2 Kottayam Adhunika Vidhyabyasathinte Vidyarthimithram, 6 Rajeshwary V.P Saithathikadisthanangal-2 Kottayam MalayalaBasha Bodhanathinte Vidyarthimithram, 7 Saithathikadisthanam (Pradhesika Rajapan Nair P.K Kottayam Bashabothanam-1) MalayalaBasha Bodhanathinte Vidyarthimithram, 8 Saithathikadisthanam (Pradhesika Rajapan Nair P.K Kottayam Bashabothanam-1) Samuhyashasthra Vidyarthimithram, 9 Vidhyabyasathinte saithadhika Thomas R.S Kottayam Adisthanangal-2 Samuhyashasthra Vidyarthimithram, 10 Vidhyabyasathinte saithadhika Thomas R.S Kottayam Adisthanangal-2 Samaniashasthra Vidhyabyasathinte Vidyarthimithram, 11 saithadhika Rajeshwary V.P Kottayam Adisthanangal-2 Samaniashasthra Vidhyabyasathinte Vidyarthimithram, 12 saithadhika Rajeshwary V.P Kottayam Adisthanangal-2 Samaniashasthra Vidhyabyasathinte Vidyarthimithram, 13 saithadhika Rajeshwary V.P Kottayam Adisthanangal-2 MalayalaBasha Bodhanathinte Vidyarthimithram, 14 Saithathikadisthanam (Pradhesika Rajapan Nair P.K Kottayam Bashabothanam-2) MalayalaBasha -

The Making of Modern Malayalam Prose and Fiction: Translations from European Languages Into Malayalam in the First Half of the Twentieth Century

The Making of Modern Malayalam Prose and Fiction: Translations from European Languages into Malayalam in the First Half of the Twentieth Century K.M. Sherrif Abstract Translations from European languages have played a crucial role in the evolution of Malayalam prose and fiction in the first half of the Twentieth Century. Many of them are directly linked to the socio- political movements in Kerala which have been collectively designated ‘Kerala’s Renaissance.’ The nature of the translated texts reveal the operation of ideological and aesthetic filters in the interface between literatures, while the overwhelming presence of secondary translations indicate the hegemonic status of English as a receptor language. The translations never occupied a central position in the Malayalam literature and served mostly as mere literary and political stimulants. Keywords: Translation - evolution of genres, canon - political intervention The role of translation in the development of languages and literatures has been extensively discussed by translation scholars in the West during the last quarter of a century. The proliferation of diachronic translation studies that accompanied the revolutionary breakthroughs in translation theory in the mid-Eighties of the Twentieth Century resulted in the extensive mapping of the intervention of translation in the development of discourses and shifts of ideological paradigms in cultures, in the development of genres and the construction and disruption of the canon in literatures and in altering the idiomatic and structural paradigms of languages. One of the most detailed studies in the area was made by Andre Lefevere (1988, pp 75-114) Lefevere showed with convincing 118 Translation Today K.M. -

Malayalam - Novel

NEW BOMBAY KERALEEYA SAMAJ , LIBRARY LIBRARY LIST MALAYALAM - NOVEL SR.NO: BOOK'S NAME AUTHOR TYPE 4000 ORU SEETHAKOODY A.A.AZIS NOVEL 4001 AADYARATHRI NASHTAPETTAVAR A.D. RAJAN NOVEL 4002 AJYA HUTHI A.N.E. SUVARNAVALLY NOVEL 4003 UPACHAPAM A.N.E. SUVARNAVALLY NOVEL 4004 ABHILASHANGELEE VIDA A.P.I. SADIQ NOVEL 4005 GREEN CARD ABRAHAM THECKEMURY NOVEL 4006 TARSANUM IRUMBU MANUSHYARUM ADGAR RAICE BAROSE NOVEL 4007 TARSANUM KOLLAKKARUM ADGAR RAICE BAROSE NOVEL 4008 PATHIMOONNU PRASNANGAL AGATHA CHRISTIE D.NOVEL 4009 ABC NARAHATHYAKAL AGATHA CHRISTIE D.NOVEL 4010 HARITHABHAKALKK APPURAM AKBAR KAKKATTIL NOVEL 4011 ENMAKAJE AMBIKA SUDAN MANGAD NOVEL 4012 EZHUTHATHA KADALAS AMRITA PRITAM NOVEL 4013 MARANA CERTIFICATE ANAND NOVEL 4014 AALKKOOTTAM ANAND NOVEL 4015 ABHAYARTHIKAL ANAND NOVEL 4016 MARUBHOOMIKAL UNDAKUNNATHU ANAND NOVEL 4017 MANGALAM RAHIM MUGATHALA NOVEL 4018 VARDHAKYAM ENDE DUKHAM ARAVINDAN PERAMANGALAM NOVEL 4019 CHORAKKALAM SIR ARTHAR KONAN DOYLE D.NOVEL 4020 THIRICHU VARAVU ASHTAMOORTHY NOVEL 4021 MALSARAM ASHWATHI NOVEL 4022 OTTAPETTAVARUDEY RATHRI BABU KILIROOR NOVEL 4023 THANAL BALAKRISHNAN NOVEL 4024 NINGAL ARIYUNNATHINE BALAKRISHNAN MANGAD NOVEL 4025 KADAMBARI BANABATTAN NOVEL 4026 ANANDAMADAM BANKIM CHANDRA CHATTERJI NOVEL 4027 MATHILUKAL VIKAM MOHAMMAD BASHEER NOVEL 4028 ATTACK BATTEN BOSE NOVEL 4029 DR.DEVIL BATTON BOSE D.NOVEL 4030 CHANAKYAPURI BATTON BOSE D.NOVEL 4031 RAKTHA RAKSHASSE BRAM STOCKER NOVEL 4032 NASHTAPETTAVARUDEY SANGAGANAM C.GOPINATH NOVEL 4033 PRAKRTHI NIYAMAM C.R.PARAMESHWARAN NOVEL 4034 CHUZHALI C.RADHAKRISHNAN NOVEL 4035 VERUKAL PADARUNNA VAZHIKAL C.RADHAKRISHNAN NOVEL 4036 ATHIRUKAL KADAKKUNNAVAR C.RADHAKRISHNAN NOVEL 4037 SAHADHARMINI C.RADHAKRISHNAN NOVEL 4038 KAANAL THULLIKAL C.RADHAKRISHNAN NOVEL 4039 POOJYAM C.RADHAKRISHNAN NOVEL 4040 KANGALIKAL C.RADHAKRISHNAN NOVEL 4041 THEVADISHI C.RADHAKRISHNAN NOVEL 4042 KANKALIKAL C.RADHAKRISHNAN NOVEL 4043 MRINALAM C.RADHAKRISHNAN NOVEL 4044 KANNIMANGAKAL C.RADHAKRISHNAN NOVEL 4045 MALAKAMAAR CHIRAKU VEESHUMBOL C.V. -

English Books in Ksa Library

Author Title Call No. Moss N S ,Ed All India Ayurvedic Directory 001 ALL/KSA Jagadesom T D AndhraPradesh 001 AND/KSA Arunachal Pradesh 001 ARU/KSA Bullock Alan Fontana Dictionary of Modern Thinkers 001 BUL/KSA Business Directory Kerala 001 BUS/KSA Census of India 001 CEN/KSA District Census handbook 1 - Kannanore 001 CEN/KSA District Census handbook 9 - Trivandrum 001 CEN/KSA Halimann Martin Delhi Agra Fatepur Sikri 001 DEL/KSA Delhi Directory of Kerala 001 DEL/KSA Diplomatic List 001 DIP/KSA Directory of Cultural Organisations in India 001 DIR/KSA Distribution of Languages in India 001 DIS/KSA Esenov Rakhim Turkmenia :Socialist Republic of the Soviet Union 001 ESE/KSA Evans Harold Front Page History 001 EVA/KSA Farmyard Friends 001 FAR/KSA Gazaetteer of India : Kerala 001 GAZ/KSA Gazetteer of India 4V 001 GAZ/KSA Gazetteer of India : kerala State Gazetteer 001 GAZ/KSA Desai S S Goa ,Daman and Diu ,Dadra and Nagar Haveli 001 GOA/KSA Gopalakrishnan M,Ed Gazetteers of India: Tamilnadu State 001 GOP/KSA Allward Maurice Great Inventions of the World 001 GRE/KSA Handbook containing the Kerala Government Servant’s 001 HAN/KSA Medical Attendance Rules ,1960 and the Kerala Governemnt Medical Institutions Admission and Levy of Fees Rules Handbook of India 001 HAN/KSA Ker Alfred Heros of Exploration 001 HER/KSA Sarawat H L Himachal Pradesh 001 HIM/KSA Hungary ‘77 001 HUN/KSA India 1990 001 IND/KSA India 1976 : A Reference Annual 001 IND/KSA India 1999 : A Refernce Annual 001 IND/KSA India Who’s Who ,1972,1973,1977-78,1990-91 001 IND/KSA India :Questions -

Unearthing the Critical Shores of Sugathakumari's “Rathrimazha

Annals of R.S.C.B., ISSN:1583-6258, Vol. 25, Issue 5, 2021, Pages. 2853 - 2860 Received 15 April 2021; Accepted 05 May 2021. Unearthing the Critical Shores of Sugathakumari’s “Rathrimazha” (Night Rain) Aiswarya Jayan1, M. Vaishak2,Vidya S. S3 1Department of English, Amrita Viswa Vidyapeetham, Kollam,India. Email:[email protected] 2Department of English, Amrita Viswa Vidyapeetham, Kollam,India. Email:[email protected] 3Department of English, Amrita Viswa Vidyapeetham, Kollam,India. Email:[email protected] Abstract The art of translation has marked its stamp in captivating the enchanting shores of authentic Indian literature. Malayalam literature has always been exploring innumerable opportunities in the domain of literary genius. Sugathakumari, a renowned poet and activist has opened the windows to untold possibilities in uprising the elements of ecofeminism, pathetic fallacy and anti-ecological consciousness through her poem Rathrimazha. Critically comparing and contrasting the shores of Rathrimazha and its translation Night Rain has extended the prospects of understanding how the anti-ecological consciousness is employed or can be interpreted through the ecofeminist reading of the poem. Keywords: Translation, Critical Analysis, Ecofeminist Reading, Anti Ecological Consciousness. 1. Introduction: “Without translation we would be living in provinces bordering on silence” – George Steiner Translation is an intriguing art of communication that transcends the intractable boundaries of linguistic comprehension sheathed in the stifling nuances of verbal and phonetic discrepancy. The process of translation had always been an enigmatic enterprise as the intervention of cultural disparities spin out a consequential debate in regard of the authenticity of the translation and its fealty to the original.