Visual Media and the Unraveling of Thanksgiving

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

UCLA UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UCLA UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Lost! The Social Psychology of Missing Possessions Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/1rn7b11p Author Berry, Brandon Publication Date 2012 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Lost! The Social Psychology of Missing Possessions A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Sociology by Brandon Lee Berry 2012 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Lost! The Social Psychology of Missing Possessions by Brandon Lee Berry Doctor of Philosophy in Sociology University of California, Los Angeles, 2012 Professor Jack Katz, Chair For most, the loss of a material possession is an infrequent occurrence usually prevented through a variety of vaguely noticed practices and routines. For the sociologist, the occasion offers a natural experiment in how individuals deal with a sudden threat to the order, expectations, and material scaffolding sustaining their usual way of life. Drawing on 600 naturally-occurring cases of loss collected through observations around lost and found booths and counters, interviews with individuals recruited through lost and found websites, and guided journaling by college undergraduates about their everyday misplacements, this dissertation explores the social impact of a missing possession. Tracing losses from the moment of their discovery, I show how losing parties must carve out space from their ongoing biographies if a loss is to gain foothold as a social matter. In taking up the theme of ‘a loss’ as a matter to resolve, individuals will act to ensure that their immediate activities will go on as planned, that they will maintain untroubled ii relations with others, or that they will feel “complete.” Yet a central paradox is that the object’s loss may disturb them even while they concede its dispensability. -

On Strategy: a Primer Edited by Nathan K. Finney

Cover design by Dale E. Cordes, Army University Press On Strategy: A Primer Edited by Nathan K. Finney Combat Studies Institute Press Fort Leavenworth, Kansas An imprint of The Army University Press Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Finney, Nathan K., editor. | U.S. Army Combined Arms Cen- ter, issuing body. Title: On strategy : a primer / edited by Nathan K. Finney. Other titles: On strategy (U.S. Army Combined Arms Center) Description: Fort Leavenworth, Kansas : Combat Studies Institute Press, US Army Combined Arms Center, 2020. | “An imprint of The Army University Press.” | Includes bibliographical references. Identifiers: LCCN 2020020512 (print) | LCCN 2020020513 (ebook) | ISBN 9781940804811 (paperback) | ISBN 9781940804811 (Adobe PDF) Subjects: LCSH: Strategy. | Strategy--History. Classification: LCC U162 .O5 2020 (print) | LCC U162 (ebook) | DDC 355.02--dc23 | SUDOC D 110.2:ST 8. LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2020020512. LC ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2020020513. 2020 Combat Studies Institute Press publications cover a wide variety of military topics. The views ex- pressed in this CSI Press publication are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the Depart- ment of the Army or the Department of Defense. A full list of digital CSI Press publications is available at https://www.armyu- press.army.mil/Books/combat-studies-institute. The seal of the Combat Studies Institute authenticates this document as an of- ficial publication of the CSI Press. It is prohibited to use the CSI’s official seal on any republication without the express written permission of the director. Editors Diane R. -

Support for Begins to Un

The weather ■it.'-;. ITT ' ' ’ Sunny today with high near 70. In- creaiing cioudineu tonight with low SO SO. Tueiday variable cloudiness with CIWU chance ot a few showers. High in 70s. Cbahce of rain 20% tonight, 30% Tuesday. National weather forecast map on Page 7-B. FRia>:i nrr6tN.< Support for begins to un WASHINGTON (UPI) - Decision facing the committee and explainiaf a i week in the Bert Lance controversy his dealings. began t^ a y with political support for "I know that Mr. Lance hat not the White House budget director un made any such decision,” Clifford raveling as he prepared for his day in told the Washington Star. "He fecit the witness chair. he has committed no illegality and, Supporters of the former Atlanta in his opinion, no impropriety ... I banker asked only that Lance be believe it is absolutely incorrect that given a chance to answer the charges in public. 'The Senate Governmental Affairs Committee scheduled fresh Balloonil testimony from a series of govern ment officials, culminating ’Thursday with Lance’s own appearance. Carter plans a news conference Wednesday, the day before Lance call for testifies. Questions of Comptroller of the REYKJAVIK, Iceland (UPI) - Currency John Heimann were likely Two Albuquerque, N.M., men trying Army-Navy Club has family picnic to center on a newly released Inter to become the first to fly the Atlantic in a balloon, ran low on fuel today Members and families of the Army-Navy Club and Auxiliary enjoy picnicking and play nal Revenue Service report detailing efforts by Lance to conceal financial after more than 60 hours aloft and Sunday at the group’s 18th annual family picnic, at Globe Hollow. -

Abstract a Case Study of Cross-Ownership Waivers

ABSTRACT A CASE STUDY OF CROSS-OWNERSHIP WAIVERS: FRAMING NEWSPAPER COVERAGE OF RUPERT MURDOCH’S REQUESTS TO KEEP THE NEW YORK POST by Rachel L. Seeman Media ownership is an important regulatory issue that is enforced by the Federal Communications Commission. The FCC, Congress, court and public interest groups share varying viewpoints concerning what the ownership limits should be and whether companies should be granted a waiver to be excused from the rules. News Corporation is one media firm that has a history of seeking these waivers, particularly for the New York Post and television stations in same community. This study conducted a qualitative framing analysis of news articles from the New York Times and the Wall Street Journal to determine if the viewpoints expressed by the editorial boards were reflected in reports on News Corp.’s attempt to receive cross-ownership waivers. The analysis uncovered ten frames the newspapers used to assist in reporting the events and found that 80% of these frames did parallel the positions the paper’s editorial boards took concerning ownership waivers. A CASE STUDY OF CROSS-OWNERSHIP WAIVERS: FRAMING NEWSPAPER COVERAGE OF RUPERT MURDOCH’S REQUESTS TO KEEP THE NEW YORK POST A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of Miami University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Department of Communications by Rachel Leianne Seeman Miami University Oxford, OH 2009 Advisor: __________________________________ (Dr. Bruce Drushel) Reader: __________________________________ (Dr. Howard -

Alyson Hannigan Listing by Ren Smith Featured in USA Today

Alyson Hannigan listing by Ren Smith featured in USA Today February 14, 2018 Alyson Hannigan has a genius way of keeping organized at home Alyson Hannigan is giving us serious inspiration. Having trouble keeping your family’s schedule organized? Steal this fun DIY idea from actress Alyson Hannigan. The “How I Met Your Mother” star recently put her Santa Monica, California house up for sale, and we noticed a large chalkboard calendar on one of the walls in the kitchen area. It made us immediately want to grab a bucket of chalkboard paintand some wood to create one like it in our own homes. The wall features five rows of seven squares separated by narrow strips of wood. Along the top of the larger frame that surrounds the calendar are the names of the days of the week. Each box can be numbered with chalk according to the current month. It’s the perfect place to write down appointment reminders, your kids’ sports practice schedules and even menu plans for the week. And when you want to keep track of miscellaneous things — such as future vacation countdowns, phone numbers, or notes to family members — there’s a larger square on the side for that. The wall can easily be re-created with a few supplies from a home improvement store, and there are also so many variations you can do, such as using whiteboard paint as the base or creating the frame and boxes with Washi tape if you don’t want to work with wood. Hannigan, who has two young daughters, told People in 2016 that she loves to craft so much, she turned her guest house into a crafting room. -

Than a Meal: the Turkey in History, Myth

More Than a Meal Abigail at United Poultry Concerns’ Thanksgiving Party Saturday, November 22, 1997. Photo: Barbara Davidson, The Washington Times, 11/27/97 More Than a Meal The Turkey in History, Myth, Ritual, and Reality Karen Davis, Ph.D. Lantern Books New York A Division of Booklight Inc. Lantern Books One Union Square West, Suite 201 New York, NY 10003 Copyright © Karen Davis, Ph.D. 2001 All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the written permission of Lantern Books. Printed in the United States of America Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data For Boris, who “almost got to be The real turkey inside of me.” From Boris, by Terry Kleeman and Marie Gleason Anne Shirley, 16-year-old star of “Anne of Green Gables” (RKO-Radio) on Thanksgiving Day, 1934 Photo: Underwood & Underwood, © 1988 Underwood Photo Archives, Ltd., San Francisco Table of Contents 1 Acknowledgments . .9 Introduction: Milton, Doris, and Some “Turkeys” in Recent American History . .11 1. A History of Image Problems: The Turkey as a Mock Figure of Speech and Symbol of Failure . .17 2. The Turkey By Many Other Names: Confusing Nomenclature and Species Identification Surrounding the Native American Bird . .25 3. A True Original Native of America . .33 4. Our Token of Festive Joy . .51 5. Why Do We Hate This Celebrated Bird? . .73 6. Rituals of Spectacular Humiliation: An Attempt to Make a Pathetic Situation Seem Funny . .99 7 8 More Than a Meal 7. -

The Community-Centered Cult Television Heroine, 1995-2007

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Dissertations, Theses, and Student Research: Department of English English, Department of 2010 "Just a Girl": The Community-Centered Cult Television Heroine, 1995-2007 Tamy Burnett University of Nebraska at Lincoln Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/englishdiss Part of the Feminist, Gender, and Sexuality Studies Commons, Literature in English, North America Commons, and the Visual Studies Commons Burnett, Tamy, ""Just a Girl": The Community-Centered Cult Television Heroine, 1995-2007" (2010). Dissertations, Theses, and Student Research: Department of English. 27. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/englishdiss/27 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the English, Department of at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Student Research: Department of English by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. “JUST A GIRL”: THE COMMUNITY-CENTERED CULT TELEVISION HEROINE, 1995-2007 by Tamy Burnett A DISSERTATION Presented to the Faculty of The Graduate College at the University of Nebraska In Partial Fulfillment of Requirements For the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Major: English (Specialization: Women‟s and Gender Studies) Under the Supervision of Professor Kwakiutl L. Dreher Lincoln, Nebraska May, 2010 “JUST A GIRL”: THE COMMUNITY-CENTERED CULT TELEVISION HEROINE, 1995-2007 Tamy Burnett, Ph.D. University of Nebraska, 2010 Adviser: Kwakiutl L. Dreher Found in the most recent group of cult heroines on television, community- centered cult heroines share two key characteristics. The first is their youth and the related coming-of-age narratives that result. -

Frontier Re-Imagined: the Mythic West in the Twentieth Century

University of South Carolina Scholar Commons Theses and Dissertations 2018 Frontier Re-Imagined: The yM thic West In The Twentieth Century Michael Craig Gibbs University of South Carolina - Columbia Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/etd Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Gibbs, M.(2018). Frontier Re-Imagined: The Mythic West In The Twentieth Century. (Doctoral dissertation). Retrieved from https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/etd/5009 This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you by Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FRONTIER RE-IMAGINED : THE MYTHIC WEST IN THE TWENTIETH CENTURY by Michael Craig Gibbs Bachelor of Arts University of South Carolina-Aiken, 1998 Master of Arts Winthrop University, 2003 Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English College of Arts and Sciences University of South Carolina 2018 Accepted by: David Cowart, Major Professor Brian Glavey, Committee Member Tara Powell, Committee Member Bradford Collins, Committee Member Cheryl L. Addy, Vice Provost and Dean of the Graduate School © Copyright by Michael Craig Gibbs All Rights Reserved. ii DEDICATION To my mother, Lisa Waller: thank you for believing in me. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I wish to thank the following people. Without their support, I would not have completed this project. Professor Emeritus David Cowart served as my dissertation director for the last four years. He graciously agreed to continue working with me even after his retirement. -

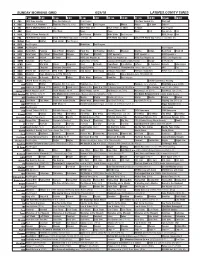

Sunday Morning Grid 6/24/18 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 6/24/18 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Face the Nation (N) Paid Program PGA Tour Special (N) PGA Golf 4 NBC Today in L.A. Weekend Meet the Press (N) (TVG) NBC4 News Paid Program House House 1st Look Extra Å 5 CW KTLA 5 Morning News at 7 (N) Å KTLA News at 9 KTLA 5 News at 10am In Touch Paid Program 7 ABC News This Week News News News Paid Eye on L.A. Paid 9 KCAL KCAL 9 News Sunday (N) Joel Osteen Schuller Mike Webb Paid Program REAL-Diego Paid 11 FOX FIFA World Cup Today 2018 FIFA World Cup Japan vs Senegal. (N) FIFA World Cup Today 2018 FIFA World Cup Poland vs Colombia. (N) 13 MyNet Paid Matter Fred Jordan Paid Program 18 KSCI Paid Program Buddhism Paid Program 22 KWHY Paid Program Paid Program 24 KVCR Paint With Painting Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Oil Painting Kitchen Mexican Martha Belton Real Food Food 50 28 KCET Zula Patrol Zula Patrol Mixed Nutz Edisons Kid Stew Biz Kid$ KCET Special Å KCET Special Å KCET Special Å 30 ION Jeremiah Youseff In Touch Paid NCIS: Los Angeles Å NCIS: Los Angeles Å NCIS: Los Angeles Å NCIS: Los Angeles Å 34 KMEX Conexión Paid Program Como Dice el Dicho La casa de mi padre (2008, Drama) Nosotr. Al Punto (N) 40 KTBN James Win Walk Prince Carpenter Jesse In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written Jeffress K. -

CLASSIFIED ADVERTISING 643-2711 Woman's Body Found In

Ik" M - MANCHESTER HERALD. Friday. May 2. 1986 I CLASSIFIED ADVERTISING 643-2711 CONNECTICUT WEEKEND PLUS , - s ^ Hartford parade Cheney tightens Young comedian "'V CARS T oH CAMPERS/ IB0AT8/MARINE I keeps on truckin’ CONOOMIWUMS « 7 y MISCELLANEOUS TAB SALES TA6 SALES FOR SALE IS^THAILEBS / salutes Whalers conference lead I EQUIPMENT FOR RENT I FURNITURE \o i\m SALE 1978 Chrysler Le Baron Four Place Trailer ( For ^ ... page 10 ... p age 11 ... magazine inside 16 foot Mad River canoe, Results of Spring Clean snowmobile, ATV, trac Brown Plold Couch. Al ing! Lots of household Station wagon, new tires, most New. Excellent con paddles Included. Used new transmission, leather tors etc.) Excellent condi four fimes. Excellent con miscellaneous. Check It tion, rear swing gate dition. $100 or best otter. Tag Sale. Moving - 1 out. Saturday May 3rd, Interior, air, $1199 or best 649-5614. dition. $800. Pleose coll Wooden Storm windows offer. 649-8158. available, 3500 lb. capac Two bedroom townhouse 643-4942 after 6pm or 647- and screens, and 150 feet Franklin Street. Manches 9-4. 24 O'Leary Drive Man ity. $1,000 649-4098 after for rent. Convenient loca 9946 8:30 - 5:30. Ask for ter 10-4, Saturday May 3rd chester Whitnev maple dining of Vj Inch PVC tubing. Call 1979 Chew Chevette, blue, 6pm^_________ tion to 1-84. Call 646-8352, Bob. 647-9221. and Sunday May 4th. osk for Don. room set. Complete only. Tag Sale - Saturday. Fur looks great, excellent run Jayco Popup - Sleeps 6, Best offer. 644-2063. ning condition. -

Thanksgiving Thanksgiving in America and Canada

Thanksgiving Thanksgiving in America and Canada PDF generated using the open source mwlib toolkit. See http://code.pediapress.com/ for more information. PDF generated at: Sat, 05 Nov 2011 00:49:59 UTC Contents Articles Pilgrims (Plymouth Colony) 1 Plymouth, Massachusetts 12 Thanksgiving 29 Thanksgiving (United States) 34 Thanksgiving (Canada) 50 Thanksgiving dinner 53 Black Friday (shopping) 57 References Article Sources and Contributors 63 Image Sources, Licenses and Contributors 65 Article Licenses License 67 Pilgrims (Plymouth Colony) 1 Pilgrims (Plymouth Colony) Pilgrims (US), or Pilgrim Fathers (UK), is a name commonly applied to early settlers of the Plymouth Colony in present-day Plymouth, Massachusetts, United States. Their leadership came from the religious congregations of Brownist English Dissenters who had fled the volatile political environment in the East Midlands of England for the relative calm and tolerance of Holland in the Netherlands. Concerned with losing their cultural identity, the group later arranged with English investors to establish a new colony in North America. The colony, established in 1620, became the second successful English settlement (after the founding of Jamestown, Virginia, in 1607) and later the oldest continuously inhabited British settlement in what was to become the United States of America. The Pilgrims' story of seeking religious freedom has become a central theme of the history and culture of the United States. History Separatists in Scrooby The core of the group that would come to be known as the Pilgrims were brought together by a common belief in the ideas promoted by Richard Clyfton, a Brownist parson at All Saints' Parish Church in Babworth, Nottinghamshire, between 1586 and 1605. -

European Journal of American Studies, 12-2 | 2017 “The Old Wild West in the New Middle East”: American Sniper (2014) and the Gl

European journal of American studies 12-2 | 2017 Summer 2017, including Special Issue: Popularizing Politics: The 2016 U.S. Presidential Election “The Old Wild West in the New Middle East”: American Sniper (2014) and the Global Frontiers of the Western Genre Lennart Soberon Electronic version URL: https://journals.openedition.org/ejas/12086 DOI: 10.4000/ejas.12086 ISSN: 1991-9336 Publisher European Association for American Studies Electronic reference Lennart Soberon, ““The Old Wild West in the New Middle East”: American Sniper (2014) and the Global Frontiers of the Western Genre”, European journal of American studies [Online], 12-2 | 2017, document 12, Online since 01 August 2017, connection on 08 July 2021. URL: http://journals.openedition.org/ ejas/12086 ; DOI: https://doi.org/10.4000/ejas.12086 This text was automatically generated on 8 July 2021. Creative Commons License “The Old Wild West in the New Middle East”: American Sniper (2014) and the Gl... 1 “The Old Wild West in the New Middle East”: American Sniper (2014) and the Global Frontiers of the Western Genre Lennart Soberon 1 While recent years have seen no shortage of American action thrillers dealing with the War on Terror—Act of Valor (2012), Zero Dark Thirty (2012), and Lone Survivor (2013) to name just a few examples—no film has been met with such a great controversy as well as commercial success as American Sniper (2014). Directed by Clint Eastwood and based on the autobiography of the most lethal sniper in U.S. military history, American Sniper follows infamous Navy Seal Chris Kyle throughout his four tours of duty to Iraq.