The Olympic Legacy Elliott Morsia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

London Dock Culture and PLACEMAKING STRATEGY Placemaking Strategy (May 2014)

CULTURAL London Dock Culture and PLACEMAKING STRATEGY Placemaking Strategy (May 2014) FUTURECITY 01 This Document is submitted in support of the application for planning permission for the redevelopment of the London Dock site, in the London Borough of Tower Hamlets (‘LBTH’). A hybrid planning application (part outline/part detailed) for redevelopment of the site was submitted to LBTH on 29 May 2013 (ref: PA/13/01276). Following submission, a number of amendments to the application were submitted in September and November 2013. The planning application put before LBTH Strategic Development Committee on 9 January 2014 comprised: “An Outline submission for demolition of all buildings and structures on the site with the exception of the Pennington Street Warehouse and Times House and comprehensive mixed use development comprising a maximum of 221,924 sq m (GEA) (excluding basement) of floorspace for the following uses: – residential (C3); – business uses including office and flexible workspace (B1); – retail, financial and professional services, food and drink uses (A1, A2, A3, A4 & A5); – community and cultural uses (D1); – a secondary school (D1); – assembly and leisure uses (D2); – energy centre, storage, car and cycle parking; and – formation of new pedestrian and vehicular access and means of access and circulation within the site together with new private and public open space. Full details submitted for 82,596 sq m GEA of floorspace (excluding basement) in five buildings - the Pennington Street Warehouse, Times House and Building Plots A, B and C comprising residential (C3), office and flexible workspaces (B1), community and leisure uses (D1/D2), retail and food and drink uses (A1, A2, A3, A4, A5) together with car and cycle parking, associated landscaping and new public realm”. -

Now We Are 126! Highlights of Our 3 125Th Anniversary

Issue 5 School logo Sept 2006 Inside this issue: Recent Visits 2 Now We Are 126! Highlights of our 3 125th Anniversary Alumni profiles 4 School News 6 Recent News of 8 Former Students Messages from 9 Alumni Noticeboard 10 Fundraising 11 A lot can happen in 12 just one year In Memoriam 14 Forthcoming 16 Performances Kim Begley, Deborah Hawksley, Robert Hayward, Gweneth-Ann Jeffers, Ian Kennedy, Celeste Lazarenko, Louise Mott, Anne-Marie Owens, Rudolf Piernay, Sarah Redgwick, Tim Robinson, Victoria Simmons, Mark Stone, David Stout, Adrian Thompson and Julie Unwin (in alphabetical order) performing Serenade to Music by Ralph Vaughan Williams at the Guildhall on Founders’ Day, 27 September 2005 Since its founding in 1880, the Guildhall School has stood as a vibrant showcase for the City of London's commitment to education and the arts. To celebrate the School's 125th anniversary, an ambitious programme spanning 18 months of activity began in January 2005. British premières, international tours, special exhibits, key conferences, unique events and new publications have all played a part in the celebrations. The anniversary year has also seen a range of new and exciting partnerships, lectures and masterclasses, and several gala events have been hosted, featuring some of the Guildhall School's illustrious alumni. For details of the other highlights of the year, turn to page 3 Priority booking for members of the Guildhall Circle Members of the Guildhall Circle are able to book tickets, by post, prior to their going on sale to the public. Below are the priority booking dates for the Autumn productions (see back cover for further show information). -

TC/1431 30 March 2021 Shahara Ali-Hempstead Development

Ref.: TC/1431 30 March 2021 Shahara Ali-Hempstead Development Management London Borough of Tower Hamlets Mulberry Place Clove Crescent E14 2BG By e-mail: [email protected] Application Reference: PA/21/00508/NC Site: Troxy, 490 Commercial Road, London, E1 0HX Proposal: Internal alterations and reinstatement works to include: ? Foyer + Lobby Removal of non-original box office and making good, removal of suspended access ceiling in lobby, revealing original metal coffers/repair, new Internal Doors - temporary to match existing, temporary free- standing Box Office in location of existing Security and removal of non-original partitions at Mezzanine Foyer and provision of new temporary free-standing bar ? WC + facilities Upgrades Refurbishment of WCs generally, removal of non-original partitions in former waiting room space and installation of new WCs, new cloakroom provision and associated circulation/way-finding improvements ? Stage + Auditorium Removal of non-original partitions to Stage + Wings, repairs to smoke lantern ? Ventilation improvements Repair/Replace MEP, check existing ductwork and reverse flow - clean and repair existing grilles ? Other minor associated works Remit: The Theatres Trust is the national advisory public body for theatres. We were established through the Theatres Trust Act 1976 'to promote the better protection of theatres' and provide statutory planning advice on theatre buildings and theatre use in England through The Town and Country Planning (Development Management Procedure) (England) Order 2015, requiring the Trust to be consulted by local authorities on planning applications which include 'development involving any land on which there is a theatre'. Comment: Thank you for consulting Theatres Trust regarding this application for listed building consent at the Troxy. -

BULLETIN Vol 49 No 4 July / August 2015

CINEMA THEATRE ASSOCIATION BULLETIN www.cta-uk.org Vol 49 No 4 July / August 2015 The grade II listed Ritz at Grays (Essex), where bingo is about to close, photographed in April 2004 – see Newsreel p19 Two views of just part of the Projected Picture Trust’s collection in its new home in Halifax – see Newsreel p18 FROM YOUR EDITOR CINEMA THEATRE ASSOCIATION promoting serious interest in all aspects of cinema buildings It doesn’t seem two minutes since I was writing the last editorial; —————————— time seems to come around so quickly. We have just returned from Company limited by guarantee. Reg. No. 04428776. Registered address: 59 Harrowdene Gardens, Teddington, TW11 0DJ. the CTA visit to Winchester, where we had an enjoyable – if hectic – Registered Charity No. 1100702. Directors are marked ‡ in list below. day; there will be a full report in the next Bulletin. We travelled down —————————— via Nuneaton and returned via Oxford. In both places I was able to PATRONS: Carol Gibbons Glenda Jackson CBE photograph some former cinemas I had not seen before to add to my Sir Gerald Kaufman PC MP Lucinda Lambton —————————— collection. There are still some I have missed in odd areas of the ANNUAL MEMBERSHIP SUBSCRIPTIONS country and I aim to try to get these over the next few years. Full Membership (UK) ................................................................ £29 On a recent visit to Hornsea (East Yorkshire) the car screeched to a Full Membership (UK under 25s) .............................................. £15 halt when I saw the building pictured below. It looked to have cine- Overseas (Europe Standard & World Economy) ........................ £37 matic features but I could only find references in the KYBs to the Star Overseas (World Standard) ....................................................... -

539-541 Commercial Road, E1 539-541 Commercial Road, London E1 0HQ

AVAILABLE TO LET 539-541 Commercial Road, E1 539-541 Commercial Road, London E1 0HQ Retail for rent, 2,001 sq ft, £65,000 per annum Iftakhar Khan [email protected] To request a viewing call us on 0203 911 3666 For more information visit https://realla.co/m/41379-539-541-commercial-road-e1-539-541-commercial-road 539-541 Commercial Road, E1 539-541 Commercial Road, London E1 0HQ To request a viewing call us on 0203 911 3666 A1 Retail/Showroom Unit - Limehouse Retail Opportunity The site is located on Commercial Road(A13), close to The Troxy and within a few minutes walk to Limehouse station (C2C and DLR). Numerous bus routes also serve this section of Commercial Road - one of the main road routes connecting East London to the City and Canary Wharf. Part of a new mixed use development on the junction of Commercial Road & Head Street – just west of the Limehouse Link tunnel. Highlights Ceiling heights ranging from 3.2 metre to 4.06 metre Ideal for a range of A1 uses –A2, B1 & D1 uses also considered subject to necessary consents 2001 sq ft floor area divided over ground floor, rear ground floor plus More information basement storage Primary ground floor retail area 912 sq ft, Raised ground floor office area 314 sq ft Rear ground floor storage area 775 sq ft Visit microsite The building is undergoing major refurbishment https://realla.co/m/41379-539-541-commercial-road-e1-539-541- Property details commercial-road Rent £65,000 per annum Contact us Building type Retail Stirling Ackroyd 40 Great Eastern Street, London EC2A 3EP Planning -

WINTER, 1962-63 VOL. 4, NO. 4 I JOURNALOF THEAMERICAN ASSOCIATION of THEATREORGAN ENTHUSIASTS B E A

WINTER, 1962-63 VOL. 4, NO. 4 I JOURNALOF THEAMERICAN ASSOCIATION OF THEATREORGAN ENTHUSIASTS b e a , -~' ;-.. t) " • • ~- ---- I t-,, -j~i,:,~.. 7•~;:,-· ·'· ;;::.: '· .-;'i.'ft ·~· r e 0 r g Douglas Reeve, Organist, at Dome Organ, Brighton, England. Story on Page 4. a Also in this Issue: LOGAN WURLITZER • "MISSING LINK" • WURLITZER LIST . Bismarck, North Dakota, Chosen for 1963 Annual Meeting. D George Wright to be one of the Performing Artists. See page 3. ,.. ' "ORGAN ADVENTURE INTO CINEMA PAST" S. F. Fox Soon to be "Just a Memor y" AT SAN FRANCISCO FOX THEATRE At midnight on Sa turday, December 1, nearly 3000 orga n buffs gathered at the F ox Thea tre in San Fran c isc o to witne s s an tt Organ Adve nture Int o Th e Cinema Pa s t", as the tick ets for the ev e nt called it. Littl e did anyone realize the marvelous treat in store for them until Gay lord Carter, the star of the evening, came up out of the pit at the console of the delightful 4 manual 36 rank Wurlitzer! For the next three hours, Carter held his audience spell bound, as he cavorted through color ful reminiscing of his career as a theatre organist, demonstrating the types of playing used for various silent movie situations and bringing on the vau.deville comedians (and doing it again when they missed their cue, etc.). Every one participated in the sing time presentation, complete with slides, parodies, and th~ operator missing the (Above) The 5,000 seat auditorium of the Fox Theatre in San -=rancisco . -

Paul L Martin

Paulus, The Cabaret Geek Cabaret Artist & Compère 3 Gibbs Square, London, SE19 1JN Tel: +44 (0)7905 259060; [email protected] www.thecabaretgeek.com PROFILE With over 30 years’ experience and hundreds of shows to his credit, Paulus is one of the UK’s best-loved cabaret artists. His warm, witty shows are always self-curated and he writes all his own links, jokes and stories. He also regularly hosts cabaret and burlesque events on the London scene and across the UK. In 2018 Paulus became known to millions of television viewers across the country, during his stint as the hard-to- impress judge on award-winning BBC1 talent show format, ALL TOGETHER NOW for two series and a Christmas Celebrity special. He has also made television shows for Sky & C4. LONDON APPEARANCES Theatre Museum The Pigalle Club Café de Paris The Café Royal Shaftesbury Theatre Hackney Empire Jermyn St. Theatre The Old Vic Pit Bar CellarDoor Soho Revue Bar The Lost Society Royal Vauxhall Tavern Volupté Kings Head, Islington National Theatre Her Majesty’s Theatre The Cobden Club Home House Empire Casino New Wimbledon Theatre The Arts Theatre New Players’ Theatre Bar Madame Jo-Jo’s Bethnal Green Working Men’s Club Adelphi Theatre Troxy Bunga Bunga Leicester Square Theatre The Space The Two Brewers Circus Toulouse Lautrec Jazz Club Pizza on the Park The Pheasantry The Crazy Coqs The Battersea Barge Too2Much Kabarett The Albany, Deptford The Rah Rah Rooms Lincoln Lounge Central Station Salvador & Amanda The Albany, Great Portland St Jerusalem The Glory Century Club -

Troxy 3 Cover Report

Committee : Date Classification Report No. Agenda Item No. Licensing Sub Committee 30 October 2014 Unclassified LSC 48/145 Report of David Tolley Head of Consumer and Business Regulation Title: Licensing Act 2003 Temporary Event Notice for the Troxy, 490 Commercial Road, LondonE1 0HX Originating Officer: Kathy Driver Principal Licensing Officer Ward affected:Shadwell 1.0 Summary Applicant: Deepak Sharma Address of Premises: Troxy 490 Commercial Road London E1 0X Objectors: Metropolitan Police 2.0 Recommendations 2.1 That the Licensing Committee considers the application and objections then adjudicates accordingly. LOCAL GOVERNMENT 2000 (Section 97) LIST OF "BACKGROUND PAPERS" USED IN THE DRAFTING OF THIS REPORT Brief description of "background paper" Tick if copy supplied for If not supplied, name and telephone register number of holder File Only Kathy Driver 020 7364 5171 3.0 Background 3.1 This is an application for a Standard Temporary Event Notice. 3.2 Enclosed is a copy of the application. See Appendix 1. 3.3 The applicant has described the nature of the application as follows: The supply of alcohol Regulated Entertainment Late Night Refreshment 3.4 The premises that has been applied for is:Troxy, 490 Commercial Road, London E14 0HX 3.5 The dates that have been applied for are as follows: 1st to 2nd November 2014 3.6 The times that have been applied for are as follows: 21:00 hours to 06:00 hours 4.0 Premises 4.1 The venue has a premises licence in place with conditions attached, a copy of the licence is attached in Appendix 2. -

Shared Ownership the Kiln Works Shaped by the Past, Made for the Future

SHARED OWNERSHIP THE KILN WORKS SHAPED BY THE PAST, MADE FOR THE FUTURE You can feel it in the air in Limehouse, where the true spirit of east London is alive and well. It is present in the nearby glittering towers of Canary Wharf. In the famous street markets where people created and built businesses. In the neighbourhoods where artists and writers like Charles Dickens were inspired. In the green open spaces where families play and aspiring athletes train. In this same spirit, Notting Hill Genesis is proud to present The Kiln Works, an exciting collection of just eleven 1 & 2 bedroom apartments, available to buy through Shared Ownership. Connect with the spirit of the past, 2 connect with contemporary London. Computer generated image of The Kiln Works. SHAPE YOUR LIFESTYLE Local photography in Limehouse. Enjoy a cycle ride along the River Thames. From your desk in the City you can be home When it comes to living the good Limehouse at The Kiln Works in well under 30 minutes with life, you’re close enough to The Grapes and plenty of energy left to make the most of life The Narrow, two fantastic pubs on Narrow in Limehouse. Street, to make them your local. There are acres of open green space in which The Grapes, at number 76, is a Georgian gem to walk, cycle, exercise or just hang out that was once the haunt of Charles Dickens and including Mile End Park, home to Mile End has been at its present location since the 1720s. Leisure Centre and the Climbing Wall. -

From Trocadero to Troxy: a Tradition Returns Transcript

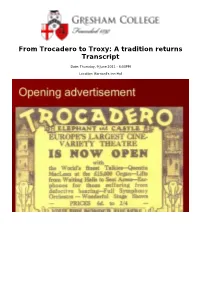

From Trocadero to Troxy: A tradition returns Transcript Date: Thursday, 9 June 2011 - 6:00PM Location: Barnard's Inn Hall 9 June 2011 From Trocadero to Troxy: A tradition returns John Abson and Richard HILLS FRCO Introduction (John Abson) The Hyams family Our story starts with three brothers - Phil, Sid and Mick Hyams. The eldest, Phil, started in the trade by working as a teenager in the new Popular cinema in the Commercial Road, Stepney. The new Popular was partly financed by the brothers' father, Hyam Hyams, a Russian immigrant and nephew of the founders of the well-known London chain of Grodzinski's bakeries. Phil was joined by his brother Sid and built up a small circuit that included the Canterbury in Westminster Bridge Road. In 1927 the Hyams converted a vast tram shed into their first super cinema: the 2,700 seat Broadway at Stratford, east London. This was also the Hyams first contact with the Wurlitzer pipe organ; the Broadway was equipped with one of this country’s early examples and the experience no doubt inspired what today would be called ‘brand loyalty’, as this story tells. Thanks to a versatile and gifted architect, George Coles, the Broadway auditorium looked palatial and Coles went on to design all the cinemas the Hyams initiated. Coles was credited with the designs for over 80 cinemas, including many for Oscar Deutsch’s Odeon chain. In 1928, the Hyams sold their circuit to the newly formed Gaumont British combine, then started afresh as H&G Kinemas in partnership with Major A.J. -

London Opera Centre

London Opera Centre GRAHAM WALNE If your taxi driver has grey hair ask for the stage itself- the journey "out front" taking scene and a storm for good measure. Just old Troxy Cinema, Stepney, then sit back 20 minutes- and thus only really saw the about every basic efTect in the catalogue and and listen to memories of one of the largest lighting at dress rehearsal; fortunately he I used all of them with glee. cine variety theatres of the thirties. Younger liked what he saw. At first the sheer size was daunting but the drivers need LO be asked for "The London He kept the brief very simple. There was methodical one-spot-at-a-time planning soon Opera Centre, Commercial Road"-the to be a backlit battle, some ships and a river, cut the area down to size. Lighting was building's function from 1963 until next plenty of gobos, a moon and stars and a hell easier than I thought-simply because all year. On my first taxi ride I considered my new appointment as lighting consultant on all the Centre's productions and tutor to the stage management course- taking over from the editor. The first test came at Christmas 1975 with the first known London production of the I 7Lh century opera "Alceste" by Lully. Among the restncttons imposed by theatres on those who work within, lack of space must be very common, but at the Centre it is the opposite which becomes a problem, for the auditorium has been turned into one of the largest performing areas in England, 100 ft deep and I 00-ft at its widest point with 60-ft to the roof. -

Gig” “This Won’T TICKETS Be Just MONKEYSARCTICTO SEE

Gruff Rhys Pete Doherty Wolf Alice SECRET ALBUM DETAILS! Tune-Yards “I’ve been told not to tell but…” 24 MAY 2014 MAY 24 The Streets IAN BROWN IAN “This won’t Arctic be just another gig” Monkeys “It’s not where you’re from, it’s where you’re at...” on their biggest weekend yet and what lies beyond ***R U going to be down the front?*** Interviews with the stellar Finsbury Park line-up Miles Kane Tame Impala Royal Blood The Amazing Snakeheads TICKETS TO SEE On the town with Arctics’ THE PAST, PRESENT favourite new band ARCTIC & FUTURE OF MUSIC WIN 24 MAY 2014 | £2.50 HEADLINE US$8.50 | ES€3.90 | CN$6.99 MONKEYS BLACK YELLOW MAGENTA CYAN 93NME14021105.pgs 16.05.2014 12:29 BLACK YELLOW MAGENTA CYAN 93NME14018164.pgs 25.04.2014 13:55 ESSENTIAL TRACKS NEW MUSICAL EXPRESS | 24 MAY 2014 4 SOUNDING OFF 8 THE WEEK THIS WEEK 16 IN THE STUDIO Pulled Apart By Horses 17 ANATOMY OF AN ALBUM The Streets – WE ASK… ‘A Grand Don’t Come For Free’ NEW 19 SOUNDTRACK OF MY LIFE Anton Newcombe, The Brian Jonestown Massacre BANDS TO DISCOVER 24 REVIEWS 40 NME GUIDE → THE BAND LIST 65 THIS WEEK IN… Alice Cooper 29 Lykke Li 6, 37 Anna Calvi 7 Lyves 21 66 THINK TANK The Amazing Mac Miller 6 Snakeheads 52 Manic Street Arctic Monkeys 44 Preachers 7 HOW’s PETE SPENDING Art Trip And The Michael Jackson 28 ▼FEATURES Static Sound 21 Miles Kane 50 Benjamin Booker 20 Mona & Maria 21 HIS TIME BEFORE THE Blaenavon 32 Morrissey 6 Bo Ningen 33 Mythhs 22 The Brian Jonestown Nick Cave 7 Massacre 19 Nihilismus 21 LIBS’ COMEBACK? Chance The Rapper 7 Oliver Wilde 37 Charli XCX 32 Owen Pallett 27 He’s putting together a solo Chelsea Wolfe 21 Palm Honey 22 8 Cheerleader 7 Peace 32 record in Hamburg Clap Your Hands Phoria 22 Say Yeah 7 Poliça 6 The Coral 15 Pulled Apart By 3 Courtly Love 22 Horses 16 IS THERE FINALLY Courtney Barnett 31 Ratking 33 Arctic Monkeys Courtney Love 36 Rhodes 6 Barry Nicolson gets the skinny Cymbals Eat Guitars 7 Royal Blood 51 A GOOD Darlia 40 Röyksopp & Robyn 27 on their upcoming Finsbury Echo & The San Mei 22 Park shows.