Requiem for a River: Ecological Consciousness in the Writings of M.T Vasudevan Nair

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

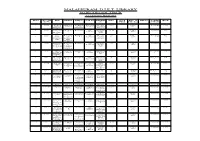

Complete List of Books in Library Acc No Author Title of Book Subject Publisher Year R.No

Complete List of Books in Library Acc No Author Title of book Subject Publisher Year R.No. 1 Satkari Mookerjee The Jaina Philosophy of PHIL Bharat Jaina Parisat 8/A1 Non-Absolutism 3 Swami Nikilananda Ramakrishna PER/BIO Rider & Co. 17/B2 4 Selwyn Gurney Champion Readings From World ECO `Watts & Co., London 14/B2 & Dorothy Short Religion 6 Bhupendra Datta Swami Vivekananda PER/BIO Nababharat Pub., 17/A3 Calcutta 7 H.D. Lewis The Principal Upanisads PHIL George Allen & Unwin 8/A1 14 Jawaherlal Nehru Buddhist Texts PHIL Bruno Cassirer 8/A1 15 Bhagwat Saran Women In Rgveda PHIL Nada Kishore & Bros., 8/A1 Benares. 15 Bhagwat Saran Upadhya Women in Rgveda LIT 9/B1 16 A.P. Karmarkar The Religions of India PHIL Mira Publishing Lonavla 8/A1 House 17 Shri Krishna Menon Atma-Darshan PHIL Sri Vidya Samiti 8/A1 Atmananda 20 Henri de Lubac S.J. Aspects of Budhism PHIL sheed & ward 8/A1 21 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad Bhagabatam PHIL Dhirendra Nath Bose 8/A2 22 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad PHIL Oriental Pub. 8/A2 Bhagabatam VolI 23 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad PHIL Oriental Pub. 8/A2 Bhagabatam Vo.l III 24 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad Bhagabatam PHIL Oriental Pub. 8/A2 25 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad PHIL Oriental Pub. 8/A2 Bhagabatam Vol.V 26 Mahadev Desai The Gospel of Selfless G/REL Navijvan Press 14/B2 Action 28 Shankar Shankar's Children Art FIC/NOV Yamuna Shankar 2/A2 Number Volume 28 29 Nil The Adyar Library Bulletin LIT The Adyar Library and 9/B2 Research Centre 30 Fraser & Edwards Life And Teaching of PER/BIO Christian Literature 17/A3 Tukaram Society for India 40 Monier Williams Hinduism PHIL Susil Gupta (India) Ltd. -

Mist: an Analytical Study Focusing on the Theme and Imagery of the Novel

[ VOLUME 5 I ISSUE 3 I JULY– SEPT 2018] E ISSN 2348 –1269, PRINT ISSN 2349-5138 Mist: An Analytical Study Focusing on the Theme and Imagery of the Novel *Arya V. Unnithan Guest Lecturer, NSS College for Women, Karamana, Trivandrum, Kerala Received: May 23, 2018 Accepted: June 30, 2018 ABSTRACT Mist, the Malayalam novel is certainly a golden feather in M.T. Vasudevan Nair’s crown and is a brilliant work which has enhanced Malayalam literature’s fame across the world. This novel is truly different from M.T.’s other writings such as Randamuzham or its English translation titled Bhima. M.T. is a writer with wonderfulnarrative skills. In the novel, he combined his story- telling power with the technique of stream- of- consciousness and thereby provides readers, a brilliant reading experience. This paper attempts to analyse the novel, with special focus on its theme and imagery, thereby to point out how far the imagery and symbolism agrees with the theme of the novel. Keywords: analysis-theme-imagery-Vimala-theme of waiting- love and longing- death-stillness Introduction: Madath Thekkepaattu Vasudevan Nair, popularly known as M.T., is an Indian writer, screenplay writer and film director from the state of Kerala. He is a creative and gifted writer in modern Malayalam literature and is one of the masters of post-Independence Indian literature. He was born on 9 August 1933 in Kudallur, a village in the present day Pattambi Taluk in Palakkad district. He rose to fame at the age of 20, when he won the prize for the best short story in Malayalam at World Short Story Competition conducted by the New York Herald Tribune. -

Masculinity and the Structuring of the Public Domain in Kerala: a History of the Contemporary

MASCULINITY AND THE STRUCTURING OF THE PUBLIC DOMAIN IN KERALA: A HISTORY OF THE CONTEMPORARY Ph. D. Thesis submitted to MANIPAL ACADEMY OF HIGHER EDUCATION (MAHE – Deemed University) RATHEESH RADHAKRISHNAN CENTRE FOR THE STUDY OF CULTURE AND SOCIETY (Affiliated to MAHE- Deemed University) BANGALORE- 560011 JULY 2006 To my parents KM Rajalakshmy and M Radhakrishnan For the spirit of reason and freedom I was introduced to… This work is dedicated…. The object was to learn to what extent the effort to think one’s own history can free thought from what it silently thinks, so enable it to think differently. Michel Foucault. 1985/1990. The Use of Pleasure: The History of Sexuality Vol. II, trans. Robert Hurley. New York: Vintage: 9. … in order to problematise our inherited categories and perspectives on gender meanings, might not men’s experiences of gender – in relation to themselves, their bodies, to socially constructed representations, and to others (men and women) – be a potentially subversive way to begin? […]. Of course the risks are very high, namely, of being misunderstood both by the common sense of the dominant order and by a politically correct feminism. But, then, welcome to the margins! Mary E. John. 2002. “Responses”. From the Margins (February 2002): 247. The peacock has his plumes The cock his comb The lion his mane And the man his moustache. Tell me O Evolution! Is masculinity Only clothes and ornaments That in time becomes the body? PN Gopikrishnan. 2003. “Parayu Parinaamame!” (Tell me O Evolution!). Reprinted in Madiyanmarude Manifesto (Manifesto of the Lazy, 2006). Thrissur: Current Books: 78. -

Malayalam - Novel

NEW BOMBAY KERALEEYA SAMAJ , LIBRARY LIBRARY LIST MALAYALAM - NOVEL SR.NO: BOOK'S NAME AUTHOR TYPE 4000 ORU SEETHAKOODY A.A.AZIS NOVEL 4001 AADYARATHRI NASHTAPETTAVAR A.D. RAJAN NOVEL 4002 AJYA HUTHI A.N.E. SUVARNAVALLY NOVEL 4003 UPACHAPAM A.N.E. SUVARNAVALLY NOVEL 4004 ABHILASHANGELEE VIDA A.P.I. SADIQ NOVEL 4005 GREEN CARD ABRAHAM THECKEMURY NOVEL 4006 TARSANUM IRUMBU MANUSHYARUM ADGAR RAICE BAROSE NOVEL 4007 TARSANUM KOLLAKKARUM ADGAR RAICE BAROSE NOVEL 4008 PATHIMOONNU PRASNANGAL AGATHA CHRISTIE D.NOVEL 4009 ABC NARAHATHYAKAL AGATHA CHRISTIE D.NOVEL 4010 HARITHABHAKALKK APPURAM AKBAR KAKKATTIL NOVEL 4011 ENMAKAJE AMBIKA SUDAN MANGAD NOVEL 4012 EZHUTHATHA KADALAS AMRITA PRITAM NOVEL 4013 MARANA CERTIFICATE ANAND NOVEL 4014 AALKKOOTTAM ANAND NOVEL 4015 ABHAYARTHIKAL ANAND NOVEL 4016 MARUBHOOMIKAL UNDAKUNNATHU ANAND NOVEL 4017 MANGALAM RAHIM MUGATHALA NOVEL 4018 VARDHAKYAM ENDE DUKHAM ARAVINDAN PERAMANGALAM NOVEL 4019 CHORAKKALAM SIR ARTHAR KONAN DOYLE D.NOVEL 4020 THIRICHU VARAVU ASHTAMOORTHY NOVEL 4021 MALSARAM ASHWATHI NOVEL 4022 OTTAPETTAVARUDEY RATHRI BABU KILIROOR NOVEL 4023 THANAL BALAKRISHNAN NOVEL 4024 NINGAL ARIYUNNATHINE BALAKRISHNAN MANGAD NOVEL 4025 KADAMBARI BANABATTAN NOVEL 4026 ANANDAMADAM BANKIM CHANDRA CHATTERJI NOVEL 4027 MATHILUKAL VIKAM MOHAMMAD BASHEER NOVEL 4028 ATTACK BATTEN BOSE NOVEL 4029 DR.DEVIL BATTON BOSE D.NOVEL 4030 CHANAKYAPURI BATTON BOSE D.NOVEL 4031 RAKTHA RAKSHASSE BRAM STOCKER NOVEL 4032 NASHTAPETTAVARUDEY SANGAGANAM C.GOPINATH NOVEL 4033 PRAKRTHI NIYAMAM C.R.PARAMESHWARAN NOVEL 4034 CHUZHALI C.RADHAKRISHNAN NOVEL 4035 VERUKAL PADARUNNA VAZHIKAL C.RADHAKRISHNAN NOVEL 4036 ATHIRUKAL KADAKKUNNAVAR C.RADHAKRISHNAN NOVEL 4037 SAHADHARMINI C.RADHAKRISHNAN NOVEL 4038 KAANAL THULLIKAL C.RADHAKRISHNAN NOVEL 4039 POOJYAM C.RADHAKRISHNAN NOVEL 4040 KANGALIKAL C.RADHAKRISHNAN NOVEL 4041 THEVADISHI C.RADHAKRISHNAN NOVEL 4042 KANKALIKAL C.RADHAKRISHNAN NOVEL 4043 MRINALAM C.RADHAKRISHNAN NOVEL 4044 KANNIMANGAKAL C.RADHAKRISHNAN NOVEL 4045 MALAKAMAAR CHIRAKU VEESHUMBOL C.V. -

Chapter V , Para 25

ANNEXURE 5.8 (CHAPTER V , PARA 25) FORM 9 List of Applications for inclusion received in Form 6 Designated location identity (where Constituency (Assembly/£Parliamentary): Mettuppalayam Revision identity applications have been received) 1. List number@ 2. Period of applications (covered in this list) From date To date 18/12/2020 18/12/2020 3. Place of hearing * Serial number$ Date of receipt Name of claimant Name of Place of residence Date of Time of of application Father/Mother/ hearing* hearing* Husband and (Relationship)# 1 18/12/2020 SATHIRAJ CHINNSAMY (F) 20-1/14A, SELVAPURAM ANNUR ROAD , Karamadai, , 2 18/12/2020 Suresh peter George fernandez (F) 8/99, Kurinji Nagar, Jadayampalayam Pudur, , 3 18/12/2020 sabariswaran nagaraj (F) 71/20a, kamaraj nager 2 nd sabsreeshwaran street , mettupalayam, , 4 18/12/2020 fowmithajasmine jamalmohammad (F) 15/6b, matharrowthar line, annajirao road, , 5 18/12/2020 Uma Maheswari R Arun Pradeep Vijayan (H) street 4, no 18, co operative colony, Mettupalayam, , 6 18/12/2020 FAHIMA JASMINE JAMALMOHAMMAD (F) 15/6B, MATHARROWTHAR LINE, ANNAJIRAO ROAD, , 7 18/12/2020 vanitha Gurusamy (H) 21B, mahadevapuram street- 6, mettupalayam, , 8 18/12/2020 Gurusamy kumarasamy (F) 21P, mahadevapuram street - 6, mettupalayam, , 9 18/12/2020 GLADY PRINCY DIANA LEO THOMAS 1/100, TRS HIGHWAY CITY, F X SAGAYAMARIARAJ (H) THALATHURAI, , 10 18/12/2020 indumathi bheeman bheeman (F) 2/551 N , Sivan nagar, belladhi , , 11 18/12/2020 Lawvaniya Rangaraj (F) 58/31 B, kuttaiyur , karamadai , , 12 18/12/2020 Mathura Gopal.p Palanisamy (F) 7/4, Thiruvalluvar nagar , Veerapandi , , 13 18/12/2020 Aswini madhavan Madhavan (F) 3b/1, Thiruvalluvar Nagar , Veerapandi , , 14 18/12/2020 Kamalathithan Subramaniyan (F) 20 a, Thiruvalluvar nagar , Veerapandi , , 15 18/12/2020 Valliyammal Lakshmanan (H) 7, Vinayagar kovil street , Thiruvalluvar , , 16 18/12/2020 T. -

SSR St.Thomas College, Kozhencherry September 2014

1 St. Thomas College KOZHENCHERRY, KERALA STATE- 689 641 Phone: 0468-2214 566 Fax: 0468-2215 543 Website: www.stthomascollege.info E-mail: [email protected] (Affiliated to Mahatma Gandhi University) Re-accredited by NAAC with B++ (2007) SELF STUDY REPORT Submitted to National Assessment and Accreditation Council Bangalore -560 072, India NAAC-SSR St.Thomas College, Kozhencherry September 2014 5 PREFACE he Malankara Mar Thoma Syrian Church, a staunch ally of an epoch- T making social movement of the nineteenth century, was led forward by the lamp of Reformation popularly known as „Naveekarana Prasthanam‟. Mar Thoma Church, part of the great tradition of the Malankara Syrian Church which had been formulated by St. Thomas, one of the twelve apostles of Jesus Christ, wielded education during the progressive period of Reformation in Kerala, as a mighty weapon for the liberation of the downtrodden masses from their stigmatized ignorance and backwardness. The establishment of St.Thomas College at Kozhencherry in 1953, as part of the altruistic missionary zeal of the church during Reformation, was the second educational venture under the auspices of Mar Thoma Church. The founding fathers, late Most Rev. Dr. Juhanon Mar Thoma Metropolitan and late Rev. K.T.Thomas Kurumthottickal, envisaged the college as an instrument for the realization of a bold vision that aimed at providing quality education to the people of the remote hilly regions of Eastern Kerala. The last six decades of the momentous historical span of the college has borne witness to the successful fulfilment of the vision of the founding fathers. The college has gone further into newer dimensions, innovations and endeavours which are impactful and relevant to the shaping of the lives of contemporary and future generations of youngsters. -

Literary Herald ISSN: 2454-3365 an International Refereed/Peer-Reviewed English E-Journal Impact Factor: 4.727 (SJIF)

www.TLHjournal.com Literary Herald ISSN: 2454-3365 An International Refereed/Peer-reviewed English e-Journal Impact Factor: 4.727 (SJIF) Vimala As An Ecofeminist: An Analysis Of M.T.Vasudevan Nair’s Mist Devisri B. M.Phil Research Scholar Nirmala College for Women Coimbatore. Abstract Kerala is the land blessed by nature with all its boons in abundance. The traditional culture of the state bears testimony to the ecological argument that the culture develops from the natural landscapes. The ecologically viable aspects of the civilization are manifest in the rich and glorious literary tradition of Malayalam which is distinctly marked by silver streaks of ecosensibility. M.T.Vasudevan Nair, one of the dominant figures on the cultural scenario of Kerala is true heir to the cultural and literary traditions of the land. This paper analyses M.T.Vasudevan Nair’s Mist (Manju) from an ecofeministic perspective. M.T. has successfully lifted the landscape onto his canvas with the life-like portrait of the woman protagonist- Vimala, in the novel. The landscape and the weather operate as pervading symbolic presence in Mist, which imparts solemnity and intensity to the human drama. Keywords: Ecosensibility, ecofeminism, landscape. Vol. 4, Issue 5 (February 2019) Dr. Siddhartha Sharma Page 47 Editor-in-Chief www.TLHjournal.com Literary Herald ISSN: 2454-3365 An International Refereed/Peer-reviewed English e-Journal Impact Factor: 4.727 (SJIF) Kerala, the land blessed by nature with all its boons in abundance- plentiful rains, backwaters and numerous rivers, a copious diversity of vegetation, beautiful landscape, fertile soil and modern climate. -

Library – Books

MALAPPURAM D I E T LIBRARY PO BP ANGADI, TIRUR Accession Register Sl No Accessi Title Author Subject Call No Publish Price Used Date of Bill No Lendin Rack on No er Fund Purchas g Mode e 1 0.003 Bhasha Board of Linguisti 410.'494 Kerala 0.00 5 Dec Lending 10/A Sasthra Editors cs (in BOA/B Bhaasha 2013 Darppana Malayala Institute n m) 2 0.02 Cherusser Cherusser Religion 200. National 12.50 4 Dec Lending 4/C y ry CHE/C Books 2013 Bharatha Stall m 3 0.03 Sree Ramanuj Religion 200. Kerala 38 4 Dec Lending 4/C Maha an RAM/S Sahitya 2013 Bhagavat Ezhuthac Akademi ham han, Thunchat hu 4 0.06 Mahabha Ramanuj Religion 200. National 30 4 Dec Lending 4/C ratham an RAM/M Books 2013 (Kilippatt Ezhuthac Stall u). han, Thunchat hu 5 0.1 OUR Sealey, Knowled 001. Macmilla 0.00 25 Nov Referenc 1/A WORLD Leonard ge SEA/O n & Co 2013 e ENCYCL Ltd OPEDIA (vOL.10) 6 0.11 MACMI Board of Knowled 001. Macmilla 0 25 Nov Referenc 1/B LLAN Editors ge BOA/M n London 2013 e ENCYCL Ltd. OPEDIA 7 0.112 Kochu Sukumar Malayala 894.812 8 Bala 0.75 16 Dec Lending 19/C Thoppica an, m 03 Sahithya 2013 ry, Tatapura Childrens SUK/K Sahakara m Literature na Sangham Ltd. 8 0.12 JUNIOR Kenneth Knowled 001. Hamlyn 0 25 Nov Referenc 1/b ENCYCL Bailey ge KEN/J 2013 e OPEDIA 9 0.122 Charithra Narayana Educatio 372.0' Kerala 75 22 Dec Lending 9/D bodhana n, KV n: 909 894 Bhaasha 2013 m (C/2) Teaching NAR/C Institute > History (in Malayala m) 10 0.135 Inguninn Kuttikris Malayala 894.812 4 Current 3.50 14 Dec Lending 18/A angolam hnamarar m Essay KUT/I Books 2013 11 0.1458 Mother Gorky, English 823. -

Rajalakshmi and Virginia Woolf: Crossing Their Paths of Creativity

Research Journal of English Language and Literature (RJELAL) A Peer Reviewed (Refereed) International Journal Vol.7.Issue 1. 2019 Impact Factor 6.8992 (ICI) http://www.rjelal.com; (Jan-Mar) Email:[email protected] ISSN:2395-2636 (P); 2321-3108(O) RESEARCH ARTICLE RAJALAKSHMI AND VIRGINIA WOOLF: CROSSING THEIR PATHS OF CREATIVITY APARNA S Department of English, Amrita Vishwa Vidyapeetham, Kollam – 690525, Kerala, India https://doi.org/10.33329/rjelal.7119.162 ABSTRACT Sensitive writers of all ages and languages have utilized their genius to evince spirit of life in their works. Writing is essential for their existence and they trudge along with inexplicable agony through the creative process that brings out their work of artistry. The measure of this agony depends on the writer’s response to his social surroundings. Those writers who stride in spiritual isolation experience this agony at its zenith. The agony further intensifies when one realizes that creative process means evincing life’s spirit with all its complexities, devoid of any external add-ons. Writers like Virginia Woolf and Malayalam writer T A Rajalakshmi (1930-1965) have experienced this agony throughout their creative life. There is a striking similarity in the pattern of creativity as far as T A Rajalakshmi and Virginia Woolf are concerned even though they were widely separated in space, time and culture. The present paper highlights this aspect in the creative writings of Rajalakshmi and Virginia Woolf and puts forward a hypothesis on the possible existence of a term Rajalakshmi effect similar to Sylvia Plath effect in literature. Key words: Malayalam literature, creativity in arts and science, Sylvia Plath effect, Rajalaksmi effect, complexity of patterns. -

A Study on Time by Mtvasudevan Nair

European Journal of Molecular & Clinical Medicine ISSN 2515-8260 Volume 07, Issue 07, 2020 Socio-Cultural Transformation: A Study On Time By M.T.Vasudevan Nair Dr. Digvijay Pandya1, Ms. Devisri B2 1Associate Professor, Department of English, Lovely Professional University, Punjab, India. 2Doctoral Research Scholar, Department of English, Punjab, India. ABSTRACT: Kerala, the land is blessed with nature and its tradition. It has a copiously diverse vegetation beautiful landscape and climate. The land is also rich in its literature. M.T.Vasudevan Nair is one of the renowned figures in Malayalam literature who excels and portrays the traditional and cultural picture of Kerala society. Kaalam, published in 1969 is a lyrical novel in Malayalam literature by M.T.Vasudevan Nair and Gita Krishnan Kutty translates it into English as Time. This paper tries to analyse the sociological and cultural transformation of Kerala in the novel Time during the period of MT. It also focuses on the system of Marumakkathayam,joint family system and its transformation. Keywords: Sociological and Cultural transformation, Marumakkathayam, Joint family system, Tarawads. India is a multi-lingual country steeped in its rich culture and tradition. There are many such treasure troves of creativity in the regional languages that would have been lost to the rest of the world, but for its tradition, which is the only means to reach a wider group of reading public. Tradition helps to understand the thought process of the people of a particular region against the backdrop of socio-cultural roots. Malayalam is one of the multifaceted languages in India. Malayalam, the mother tongue of nearly thirty million Malayalis, ninety percent of whom living in Kerala state in the south – west corner of India, belongs to the Dravidian family of languages. -

The Being of Bhasha: a General Introduction (Volume 1, Part 2) Chief Editor: G.N

The Being of Bhasha: A General Introduction (Volume 1, Part 2) Chief Editor: G.N. Devy The first volume of the People’s Linguistic Survey of India brings to the reader the journey undertaken in 2010, by a group of visionaries led by G.N. Devy to document the languages of India as they existed then. The aim of the People’s Linguistic Survey of India was to document the languages spoken in India’s remotest corners. India’s towns and cities too have found a voice in this survey. The Being of Bhasha forms the introduction to the series. 2014 978-81-250-5488-7 152 pp ` 790 Rights: World 978-81-250-5775-8 (E-ISBN) The Languages of Jammu & Kashmir (Volume 12, Part 2) Volume Editor: Omkar N. Koul The twelfth volume of the People’s Linguistic Survey of India documents the languages of the State of Jammu & Kashmir. The book is divided into three parts—the first part covers the scheduled languages, Dogri and Kashmiri; the second part, the non-scheduled and minor languages; and the third part is devoted to Sanskrit, Persian, Hindi and Urdu which have played an important role in the state and also influenced local languages. Though Urdu is the official state language, of late there has been a shift in the linguistic profile in Jammu & Kashmir as there have been some linguistic movements towards inclusion of local languages in various domains. In the discussions about the languages, there is information about their contemporary status, their historical evolution and structural aspects. The linguistic map included in the volume also gives an idea of areas where the main languages are spoken. -

Shamanism in Ted Hughes's Poetry

LANGUAGE IN INDIA Strength for Today and Bright Hope for Tomorrow Volume 19:1 January 2019 ISSN 1930-2940 Managing Editor: M. S. Thirumalai, Ph.D. Editors: B. Mallikarjun, Ph.D. Sam Mohanlal, Ph.D. B. A. Sharada, Ph.D. A. R. Fatihi, Ph.D. Lakhan Gusain, Ph.D. Jennifer Marie Bayer, Ph.D. G. Baskaran, Ph.D. L. Ramamoorthy, Ph.D. C. Subburaman, Ph.D. (Economics) N. Nadaraja Pillai, Ph.D. Renuga Devi, Ph.D. Soibam Rebika Devi, M.Sc., Ph.D. Dr. S. Chelliah, Ph.D. Assistant Managing Editor: Swarna Thirumalai, M.A. Language in India www.languageinindia.com is included in the UGC Approved List of Journals. Serial Number 49042. Materials published in Language in India www.languageinindia.com are indexed in EBSCOHost database, MLA International Bibliography and the Directory of Periodicals, ProQuest (Linguistics and Language Behavior Abstracts) and Gale Research. The journal is listed in the Directory of Open Access Journals. It is included in the Cabell’s Directory, a leading directory in the USA. Articles published in Language in India are peer-reviewed by one or more members of the Board of Editors or an outside scholar who is a specialist in the related field. Since the dissertations are already reviewed by the University-appointed examiners, dissertations accepted for publication in Language in India are not reviewed again. This is our 19th year of publication. All back issues of the journal are accessible through this link: http://languageinindia.com/backissues/2001.html Language in India www.languageinindia.com ISSN 1930-2940 19:1 January 2019 List of Contents i Contents • Periyar University Department of English, Salem, Tamilnadu, India Papers presented in the National Seminar Food is not just a Curry: Raison de'tre of Food in Literature - FDLT 2019 ..