Determining the Viability of Early Pregnancies: Two Case Reports

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

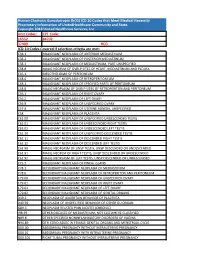

Human Chorionic Gonadotropin (Hcg) ICD 10 Codes That Meet Medical Necessity Proprietary Information of Unitedhealthcare Community and State

Human Chorionic Gonadotropin (hCG) ICD 10 Codes that Meet Medical Necessity Proprietary Information of UnitedHealthcare Community and State. Copyright 2018 United Healthcare Services, Inc Unit Codes: CPT Code: 16552 84702 37409 HCG ICD-10 Codes Covered if selection criteria are met: C38.1 MALIGNANT NEOPLASM OF ANTERIOR MEDIASTINUM C38.2 MALIGNANT NEOPLASM OF POSTERIOR MEDIASTINUM C38.3 MALIGNANT NEOPLASM OF MEDIASTINUM, PART UNSPECIFIED C38.8 MALIG NEOPLM OF OVRLP SITES OF HEART, MEDIASTINUM AND PLEURA C45.1 MESOTHELIOMA OF PERITONEUM C48.0 MALIGNANT NEOPLASM OF RETROPERITONEUM C48.1 MALIGNANT NEOPLASM OF SPECIFIED PARTS OF PERITONEUM C48.8 MALIG NEOPLASM OF OVRLP SITES OF RETROPERITON AND PERITONEUM C56.1 MALIGNANT NEOPLASM OF RIGHT OVARY C56.2 MALIGNANT NEOPLASM OF LEFT OVARY C56.9 MALIGNANT NEOPLASM OF UNSPECIFIED OVARY C57.4 MALIGNANT NEOPLASM OF UTERINE ADNEXA, UNSPECIFIED C58 MALIGNANT NEOPLASM OF PLACENTA C62.00 MALIGNANT NEOPLASM OF UNSPECIFIED UNDESCENDED TESTIS C62.01 MALIGNANT NEOPLASM OF UNDESCENDED RIGHT TESTIS C62.02 MALIGNANT NEOPLASM OF UNDESCENDED LEFT TESTIS C62.10 MALIGNANT NEOPLASM OF UNSPECIFIED DESCENDED TESTIS C62.11 MALIGNANT NEOPLASM OF DESCENDED RIGHT TESTIS C62.12 MALIGNANT NEOPLASM OF DESCENDED LEFT TESTIS C62.90 MALIG NEOPLASM OF UNSP TESTIS, UNSP DESCENDED OR UNDESCENDED C62.91 MALIG NEOPLM OF RIGHT TESTIS, UNSP DESCENDED OR UNDESCENDED C62.92 MALIG NEOPLASM OF LEFT TESTIS, UNSP DESCENDED OR UNDESCENDED C75.3 MALIGNANT NEOPLASM OF PINEAL GLAND C78.1 SECONDARY MALIGNANT NEOPLASM OF MEDIASTINUM C78.6 SECONDARY -

Histomorphological Study of Chorionic Villi in Products of Conception Following First Trimester Abortions

November, 2018/ Vol 4/ Issue 7 Print ISSN: 2456-9887, Online ISSN: 2456-1487 Original Research Article Histomorphological study of chorionic villi in products of conception following first trimester abortions Shilpa MD1, Supreetha MS2, Varshashree3 1Dr. Shilpa, MD, Assistant Professor, 2Dr. Supreetha, MS, Assistant Professor, 3Dr. Varshashree, Post graduate, all authors are affiliated with Department of Pathology, Sri Devaraj Urs Medical College, Tamaka, Kolar, Karnataka, India. Corresponding Author: Dr. Shilpa, MD, Assistant Professor, Department of Pathology, Sri Devaraj Urs Medical College, Tamaka, Kolar, Karnataka, India. Email id: [email protected] ………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………... Abstract Background: The common problem which occurs in first trimester of pregnancy is miscarriage. Retained products of conception are commonly received specimen for histopathological examination. Apart from confirmation of pregnancy, a careful examination can provide some additional information about the cause or the conditions associated with abortion. Aim: 1. To study various histopathological changes occurring in chorionic villi in first trimester spontaneous abortions and to know the pathogenesis of abortions. Materials and methods: This was a cross sectional retrospective study carried out for over a period of 3 years from January 2015 to January 2018. A total of 235biopsies were obtained from patient with the diagnosis of the first trimester spontaneous abortions were included in this study. Results: In our study most common age group of the abortion was between 21-30 years (63%). Incomplete abortion was the commonest type of abortion (47.7%). Many dysmorphic features were observed in this study like hydropic change (67%), stromal fibrosis (62%), villi with reduced blood vessels (52.7%) and perivillous fibrin deposition. -

Blighted Ovum: a Case Report

ISSN 2380-3940 WOMEN’S HEALTH Open Journal PUBLISHERS Case Report Blighted Ovum: A Case Report Aqsaa N. Chaudhry, MBA1; Frederick M. Tiesenga, MD2; Sandeep Mellacheruvu, MD, MPH3; Ryan R. Sanni, MD (Student)4* 1Saint James School of Medicine, Anguilla 2Chairman of Department of Surgery, West Suburban Medical Center, Oak Park, Illinois, USA 3Director of Clinical Research, Loretto Hospital, Chicago, Illinois, USA 4Research Assistant of Clinical Sciences, Windsor University School of Medicine, Cayon, St. Kitts and Nevis *Corresponding authors Ryan R. Sanni, MD (Student) Research Assistant of Clinical Sciences, Windsor University School of Medicine, Cayon, St. Kitts and Nevis; E-mail: [email protected] Article information Received: February 14th, 2020; Revised: February 24th, 2020; Accepted: February 25th, 2020; Published: February 27th, 2020 Cite this article Chaudhry AN, Tiesenga FM, Mellacheruvu S, Sanni RR. Blighted ovum: A case report. Women Health Open J. 2020; 6(1): 3-4.doi: 10.17140/WHOJ-6-135 ABSTRACT Presenting in her late twenties, this case report examines a G6P2 patient at 11-weeks gestation that was diagnosed with a blighted ovum, as well as the subsequent outcome and methods of additional management. A blighted ovum refers to a fertilized egg that does not develop, despite the formation of a gestational sac. The most common cause of a blighted ovum is of genetic origin. Trisomies account for most first trimester miscarriages, while consanguineous marriages result in recurrent miscarriages due to a blighted ovum. Additionally, a higher percentage of deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) damage in sperm carries a higher rate of miscarriage. Nutritional factors that may lead to a blighted ovum include low-levels of copper, prostaglandin E2, and anti-oxidative enzymes. -

Medical Abortion Reference Guide INDUCED ABORTION and POSTABORTION CARE at OR AFTER 13 WEEKS GESTATION (‘SECOND TRIMESTER’) © 2017, 2018 Ipas

Medical Abortion Reference Guide INDUCED ABORTION AND POSTABORTION CARE AT OR AFTER 13 WEEKS GESTATION (‘SECOND TRIMESTER’) © 2017, 2018 Ipas ISBN: 1-933095-97-0 Citation: Edelman, A. & Mark, A. (2018). Medical Abortion Reference Guide: Induced abortion and postabortion care at or after 13 weeks gestation (‘second trimester’). Chapel Hill, NC: Ipas. Ipas works globally so that women and girls have improved sexual and reproductive health and rights through enhanced access to and use of safe abortion and contraceptive care. We believe in a world where every woman and girl has the right and ability to determine her own sexuality and reproductive health. Ipas is a registered 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization. All contributions to Ipas are tax deductible to the full extent allowed by law. For more information or to donate to Ipas: Ipas P.O. Box 9990 Chapel Hill, NC 27515 USA 1-919-967-7052 [email protected] www.ipas.org Cover photo: © Ipas The photographs used in this publication are for illustrative purposes only; they do not imply any particular attitudes, behaviors, or actions on the part of any person who appears in the photographs. Printed on recycled paper. Medical Abortion Reference Guide INDUCED ABORTION AND POSTABORTION CARE AT OR AFTER 13 WEEKS GESTATION (‘SECOND TRIMESTER’) Alison Edelman Senior Clinical Consultant, Ipas Professor, OB/GYN Oregon Health & Science University Alice Mark Associate Medical Director National Abortion Federation About Ipas Ipas works globally so that women and girls have improved sexual and reproductive health and rights through enhanced access to and use of safe abortion and contraceptive care. -

Miscarriage Or Early Pregnancy Loss- Diagnosis and Management (Version 5)

Miscarriage or early pregnancy loss- diagnosis and management (Version 5) Guideline Readership This guideline applies to all women diagnosed with miscarriage in early pregnancy (up to 13 completed weeks) within the Heart of England Foundation Trust and to attending clinicians, sonographers and nursing staff on Gynaecology ward and early pregnancy unit. All care is tailored to individual patient needs, with an in-depth discussion of the intended risks and benefits for any intervention offered to woman with early pregnancy loss. Guideline Objectives The objective of this guideline is to enable all clinicians to recognise the different types of miscarriages and to follow a recognised management pathway so that all women with actual or suspected miscarriage receive, an appropriate and individualised care. Other Guidance Ectopic pregnancy and miscarriage: diagnosis and initial management. NICE guidance Dec 2012 Ratified Date: Insert Date Launch Date: 16 March 2018 Review Date: 16 March 2021 Guideline Author: Dr Rajmohan, Dr Cheema Contents & page numbers: 1. Flowcharts Flowchart 1 – Management of complete miscarriage p3 Flowchart 2 – Management of incomplete miscarriage p4 Flowchart 3 – Management of Missed miscarriage p5 Flowchart 4 - Management of Early fetal demise p6 Flowchart 5 – Medical management of miscarriage p7 Flowchart 6 - Surgical management (SMM) pathway p8 2. Executive summary and Overview p9 3. Body of guideline Types of miscarriage p9 Threatened miscarriage p9 Complete miscarriage p9 Incomplete miscarriage p9 Missed miscarriage -

Ectopic Pregnancy Management: Tubal and Interstitial SIGNS / SYMPTOMS DIAGNOSIS

8/29/19njm Ectopic Pregnancy Management: Tubal and interstitial SIGNS / SYMPTOMS Pain and vaginal bleeding are the hallmark symptoms of ectopic pregnancy. Pain is almost universal; it is generally lower abdominal and unilateral. Bleeding is also very common following a short period of amenorrhea. Physical exam may reveal a tender adnexal mass, often mentioned in texts, but noted clinically only 20 percent of the time. Furthermore, it may easily be confused with a tender corpus luteum of a normal intrauterine pregnancy. Finally signs and symptoms of hemoperitoneum and shock can occur, including a distended, silent, “doughy” abdomen, shoulder pain, bulging cul de sac into the posterior fornix of the vagina, and hypotension. DIAGNOSIS Initially, serum hCG rises, but then usually plateaus or falls. Transvaginal ultrasound scanning is a key diagnostic tool and can rapidly make these diagnoses: 1. Ectopic is ruled out by the presence of an intrauterine pregnancy with the exception of rare heterotopic pregnancy 2. Ectopic is proven when a gestational sac and an embryo with a heartbeat is seen outside of the uterus 3. Ectopic is highly likely if ANY adnexal mass distinct from the corpus luteum or a significant amount of free pelvic fluid is seen. When ultrasound is not definitive, correlation of serum hCG levels is important. If the hCG is above the “discriminatory zone” of 3000 mIU/ml IRP, a gestational sac should be visible on transvaginal ultrasound. The discriminatory zone varies by ultrasound machine and sonographer. If an intrauterine gestational sac is not visible by the time the hCG is at, or above, this threshold, the pregnancy has a high likelihood of being ectopic. -

Yolk Sac Size & Shape As Predictors of First Trimester Pregnancy Outcome: A

G Model JOGOH-1495; No. of Pages 6 J Gynecol Obstet Hum Reprod xxx (2018) xxx–xxx Available online at ScienceDirect www.sciencedirect.com Original Article Yolk sac size & shape as predictors of first trimester pregnancy outcome: A prospective observational study B. Suguna *, K. Sukanya Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Bangalore Baptist Hospital, Bangalore, Karnataka, India A R T I C L E I N F O A B S T R A C T Article history: Objective. – To determine the value of yolk sac size and shape for prediction of pregnancy outcome in the Received 4 August 2018 first trimester. Received in revised form 14 October 2018 +0 +6 Material and methods. – 500 pregnant women between 6 and 9 weeks of gestation underwent Accepted 17 October 2018 transvaginal ultrasound and yolk sac diameter (YSD), gestational sac diameter (GSD) were measured, Available online xxx presence/absence of yolk sac (YS) and shape of the yolk sac were noted. Follow up ultrasound was done +0 +6 to confirm fetal well-being between 11 and 12 weeks and was the cutoff point of success of Keywords: pregnancy. Yolk sac Results. – Out of 500 cases, 8 were lost to follow up, YS was absent in 14, of which 8 were anembryonic Gestational sac pregnancies. Thus, 478 out of 492 followed up cases were analyzed for YS shape and size and association Missed abortion Transvaginal ultrasound with the pregnancy outcome. In our study, abnormal yolk sac shape had a sensitivity and specificity (87.06% & 86.5% respectively, positive predictive value (PPV) of 58.2%, negative predictive value (NPV) of 96.8% in predicting a poor pregnancy outcome as compared to yolk sac diameter (sensitivity and specificity 62.3% & 64.1% respectively and PPV and NPV of 27.3% and 88.7% respectively). -

The Value of Routine Histological Examination of Curettings in All First

THE VALUE OF R(1UTINE HISTOLOGICAL EXAMINATION OF CURETTINGS IN ALL FIRST AND SECOND TRIMESTER ABORTIONS Town CHANTAL JUANITA MICHELLE STEWART M.B., Ch.B., F.C.0.G.(S.A).Cape M.R.C.O.G. of M.MED. PART III DISSERTATION (OBSTETRICS & GYNAECOLOGY) University DEPARTMENT OF OBSTETRICS AND GYNAECOLOGY UNIVERSI'IY OF CAPE TOWN AUGUST 1992 The copyright of this thesis vests in the author. No quotation from it or information derived from it is to be published without full acknowledgement of the source. The thesis is to be used for private study or non- commercial research purposes only. Published by the University of Cape Town (UCT) in terms of the non-exclusive license granted to UCT by the author. University of Cape Town THE VALUE OF ROUTINE HISTOLOGICAL EXAMINATION OF CURETI'INGS IN ALL FIRST AND SECOND TRIMESTER ABORTIONS CHANTAL JUANITA MICHELLE STEWART M.B., Ch.B., F.C.O G.(S.A). M.RC.0.G. A dissertation submitted to the University of Cape Town in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Medicine (Obstetrics & Gynaecology) Part III work on which this thesis is based is my original work ( except where acknowledgements indicate otherwise) and that neither the whole work nor any part of it has been, is being, or is to be submitted for another degree in this or any other University. I empower the University to reproduce for the purpose of research either the whole or any portion of the contents in any manner whatsoever. �);} 92 ......... oATE ............ CONTENTS 1. ABSTRACT 2. -

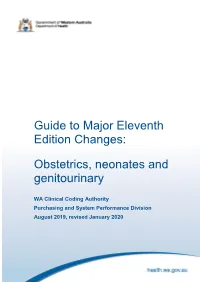

Guide to Major Eleventh Edition Changes: Obstetrics, Neonates And

Guide to Major Eleventh Edition Changes: Obstetrics, neonates and genitourinary WA Clinical Coding Authority Purchasing and System Performance Division August 2019, revised January 2020 1 Contents Chapter 15 Pregnancy, childbirth and the puerperium 3 ACS 1500 Diagnosis sequencing in obstetric episodes of care 3 ACS 1505 Delivery and assisted delivery codes 3 Delivery of baby prior to the admitted episode of care 5 ACS 1550 Discharge/transfer in labour 7 Transfer in first stage of labour 7 Transfer in third stage of labour 7 Failed induction of labour 9 Postpartum haemorrhage 9 ACS 1551 Obstetric perineal lacerations/grazes 11 ACS 1511 Termination of pregnancy (abortion) 11 ACS 1544 Complications following pregnancy with abortive outcome 14 Complications following abortion 14 Admission for retained products of conception following abortion 16 Hypoglycaemia in gestational diabetes mellitus 16 Mental Health and pregnancy 16 Neonates 16 Genitourinary 17 Acknowledgement 17 2 This guide was updated in January 2020 with creation of Examples 6, 7 and 19. Chapter 15 Pregnancy, childbirth and the puerperium Amendments include: Changes to code titles to specify ‘in pregnancy, childbirth and the puerperium.’ Changes to ACS titles for 1500 Diagnosis sequencing in obstetric episodes of care, 1511 Termination of pregnancy (abortion) and 1544 Complications following pregnancy with abortive outcome. Deletion of Excludes notes throughout ICD-10-AM to promote multiple condition coding. Clarification that codes from other chapters may be assigned to add specificity. Creation of four character codes to classify failed medical and surgical induction of labour. Indexing amendments to clarify code assignment for failed trial of labour and failure to progress unspecified, with or without identification of an underlying cause. -

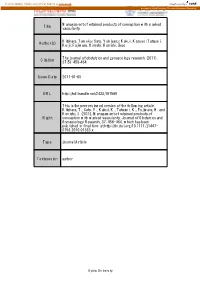

Title Management of Retained Products of Conception with Marked

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Kyoto University Research Information Repository Management of retained products of conception with marked Title vascularity. Kitahara, Tomoko; Sato, Yukiyasu; Kakui, Kazuyo; Tatsumi, Author(s) Keiji; Fujiwara, Hiroshi; Konishi, Ikuo The journal of obstetrics and gynaecology research (2011), Citation 37(5): 458-464 Issue Date 2011-01-05 URL http://hdl.handle.net/2433/197589 This is the peer reviewed version of the following article: Kitahara, T., Sato, Y., Kakui, K., Tatsumi, K., Fujiwara, H. and Konishi, I. (2011), Management of retained products of Right conception with marked vascularity. Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology Research, 37: 458‒464, which has been published in final form at http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1447- 0756.2010.01363.x Type Journal Article Textversion author Kyoto University 1 Management of Retained Products of Conception with Marked Vascularity 2 3 Tomoko Kitahara, Yukiyasu Sato*, Kazuyo Kakui, Keiji Tatsumi, Hiroshi Fujiwara, and 4 Ikuo Konishi 5 6 Department of Gynecology and Obstetrics, Kyoto University Graduate School of 7 Medicine 8 9 *Address correspondence and reprint requests to: Yukiyasu Sato, M.D., Ph.D. 10 Department of Gynecology and Obstetrics, Kyoto University Graduate School of 11 Medicine, Sakyo-ku, Kyoto 606-8507, Japan. 12 Tel; 81-75-751-3269: Fax; 81-75-761-3967: E-mail; [email protected] 13 14 Short title; Management of Hypervascular RPOC 15 Keywords; color Doppler, uterine artery embolization, expectant management 16 1 1 Abstract 2 3 Cases of retained products of conception (RPOC) with marked vascularity present a 4 clinical challenge because simple dilation and curettage (D&C) can lead to 5 life-threatening hemorrhage. -

Miscarriage Management

MISCARRIAGE MANAGEMENT Contents Purpose & Principles Scope Definitions Diagnostic Criteria Initial Assessment Management Options: a) Expectant b) Medical c) Surgical Purpose To support clinicians in the management of women who have suspected or diagnosed miscarriage Principles Women should be offered evidence – based information and support to enable them to make informed decisions about management of their pregnancy. Womens’ views and concerns are an integral component of the decision making process Scope Nursing, medical and midwifery staff in the Maternity Assessment Unit Definitions: Early Pregnancy: gestation up to 12 weeks and 6 days. (For pregnancy loss at ≥12+6/40 gestation see mifepristone protocol) Miscarriage: The recommended medical term for pregnancy loss under 20 weeks is ‘miscarriage’ in both professional and woman contexts. The term ‘abortion’ should not be used. Threatened miscarriage: a viable pregnancy is confirmed by ultrasound, but there has been an episode of PV bleeding. Missed miscarriage: a non viable intrauterine pregnancy. No fetal heart activity is seen, the gestational sac is intact, the cervix is closed and no POC have been passed. Incomplete miscarriage: some pregnancy tissue has been passed but there is a clinical or ultrasound evidence of retained tissue. Policy Number: MATY081 Facilitated by: Judy Ormandy Approved by Maternity Quality Committee Next due date: May 2016 Page 1 of 8 Complete miscarriage: all the pregnancy tissue has been passed and the uterus is empty. Anembryonic pregnancy (blighted ovum): the gestational sac has developed but the embryo hasn’t. (R)POC: (Retained) products of conception. When discussing with women & their whanau, use a term such as ‘pregnancy tissue’, not ‘products of conception’. -

Operative Hysteroscopy for Retained Products of Conception: Efficacy and Subsequent Fertility

Journal of Gynecology Obstetrics and Human Reproduction 48 (2019) 151–154 Available online at ScienceDirect www.sciencedirect.com Original Article Operative hysteroscopy for retained products of conception: Efficacy and subsequent fertility a,b, a a a Perrine Capmas *, Anina Lobersztajn , Laura Duminil , Tiphaine Barral , a,c a,b,c Anne-Gaëlle Pourcelot , Hervé Fernandez a AP-HP, Department of Gynecology and Obstetrics, Hospital Bicêtre, GHU Sud, F-94276, Le Kremlin Bicêtre, France b INSERM, U1018, Centre of research in Epidemiology and population health (CESP), F-94276, Le Kremlin Bicêtre, France c Faculty of medicine, University Paris Saclay, F-94276, Le Kremlin Bicêtre, France A R T I C L E I N F O A B S T R A C T Article history: Retained product of conception complicates nearly 1% of pregnancies and can lead to synechiae and Received 18 June 2018 compromise ulterior fertility. The aim of this study is to evaluate efficiency of operative hysteroscopy in Received in revised form 11 December 2018 management of retained products of conception (RPOC). Secondary objectives are assessments of intra- Accepted 12 December 2018 uterine adhesions rate and later fertility. Available online 12 December 2018 This unicentric retrospective study includes women who undertook an operative hysteroscopy for retained products of conception between January 2012 and March 2014. Assessment of the efficiency of Keywords: operative hysteroscopy is defined by a complete resection of retained products of conception confirmed Hysteroscopy by office hysteroscopy. Retained product of conception One hundred fourteen women were included in the study. Efficiency of operative hysteroscopy for Intra-uterine adhesions Fertility retained products of conception is 91% for women with a postoperative office hysteroscopy.