The Prestbury Civil War Hoard

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The High Sheriff Fund 2018-2019 - Programme Criteria

THE HIGH SHERIFF FUND 2018-2019 - PROGRAMME CRITERIA THE H I G H SHERIFF FUND 2 0 1 8 – 2 0 1 9 PROGRAMME CRITERIA GUIDANCE FOR APPLICANTS 1. INTRODUCTION TO THE HIGH SHERIFF FUND 2. PROGRAMME OUTCOMES 3. PROGRAMME PRIORITIES 4. GRANT FUNDING AVAILABLE 5. WHO CAN APPLY 6. FUND PARAMETERS 7. INELIGIBLE ACTIVITIES 8. QUALITY PRINCIPLES TO CONSIDER 9. WHEN TO APPLY 10. TYPICAL EXAMPLES OF ELIGIBLE PROJECTS 11. DOCUMENTS TO ACCOMPANY APPLICATION 12. FINAL TIPS WHEN APPL YING 13. FURTHER ADVICE 14. YOUR DATA WHEN APPLYING 15. COMMUNICATIONS 16. MONITORING AND EVALUATION VERSION 1 17/07/18 PAGE 1 THE HIGH SHERIFF FUND 2018-2019 - PROGRAMME CRITERIA 1. Introduction to the High Sheriff Fund Thank you for considering applying for funding through the High Sheriff Fund 2018-2019 and for taking the time to read the programme criteria. As a supporter of culture and the arts, throughout my year as High Sheriff, I will be focusing on Cheshire’s creativity and spirit of community. There is growing recognition of the value of early intervention in mental and social care through social prescribing, engaging people in cultural and local creative arts activity - as a way of combating loneliness and isolation and helping prevent the progression into worsening health and long-term conditions. We are looking forward to receiving your application and ensuring that the High Sheriff Fund 2018- 2019 can make a difference to lives of people in Cheshire West and Chester, Cheshire East, Halton and Warrington. Alexis Redmond High Sheriff of Cheshire VERSION 1 17/07/18 PAGE 2 THE HIGH SHERIFF FUND 2018-2019 - PROGRAMME CRITERIA 2. -

Summer 2017 Antonia Pugh-Thomas

Young people creating safer communities SUMMER 2017 ANTONIA PUGH-THOMAS Haute Couture Shrieval Outfits for Lady High Sheriffs 0207731 7582 659 Fulham Road London, SW6 5PY www.antoniapugh-thomas.co.uk Keystone is an independent consultancy which prioritises the needs and aspirations of its clients with their long-term interests at the centreoftheir discussions on their often-complex issues around: Family assets l Governance l Negotiation l Optimal financing structures l Accurate data capturefor informed decision-making l Mentoring and informal mediation These areall encapsulated in adeveloped propriety approach which has proved transformational as along-term strategic planning tool and ensures that all discussions around the family enterprise with its trustees and advisers arebased on accurate data and sustainable finances Advising families for the 21st Century We work with the family offices, estate offices, family businesses, trustees, 020 7043 4601 |[email protected] lawyers, accountants, wealth managers, investment managers, property or land agents and other specialist advisors www.keystoneadvisers.uk Volume 36 Issue 1 Summer 2017 the High Sheriffs’ Association of England and Wales President J R Avery Esq DL Officers and Council November 2016 to November 2017 11 14 OFFICERS Chairman J J Burton Esq DL Email [email protected] Honorary Secretary 24 34 J H A Williams Esq Gatefield, Green Tye, Much Hadham Hertfordshire SG10 6JJ Tel 01279 842225 Fax 07092 846777 Email [email protected] Honorary Treasurer N R Savory -

Sir Robert WATE Sir John WATERTON Sir Robert

Clodoreius ? Born: 0320 (app) Flavius AFRANIUS Syagrius Julius AGRICOLA Born: 0345 (app) Born: 0365 (app) Occup: Roman proconsul Occup: Roman praetorian prefect & consul Died: 0430 (app) Ferreolus ? Syagria ? ? Born: 0380 (app) Born: 0380 (app) Born: 0390 (app) Prefect Totantius FERREOLUS Papianilla ? King Sigobert the Lame of the Born: 0405 Born: 0420 (app) FRANKS Occup: Praetorian Prefect of Gaul Occup: Niece of Emperor Avitus Born: 0420 (app) Occup: King of the Franks, murdered by his son Died: 0509 (app) Senator Tonantius FERREOLUS Industria ? King Chlodoric the Parricide of Born: 0440 Born: 0450 (app) the FRANKS Occup: Roman Senator of Narbonne Born: 0450 (app) Died: 0517 Occup: King of the Franks Died: 0509 Senator Ferreolus of Saint Dode of REIMS Lothar ? NARBONNE Born: 0485 (app) Born: 0510 (app) Born: 0470 Occup: Abbess of Saint Pierre de Occup: Senator of Narbonne Reims & Saint Marr: 0503 (app) Senator Ansbertus ? Blithilde ? Born: 0520 (app) Born: 0540 (app) Occup: Gallo-Roman Senator Baudegisel II of ACQUITAINE Oda ? Arnaold of METZ Oda ? Carloman ? Arnaold of METZ Oda ? Saint Arnulf of METZ Saint Doda of METZ Born: 0550 (app) Born: 0560 (app) Born: 0560 (app) Born: 0570 (app) Born: 0550 (app) Born: 0560 (app) Born: 0570 (app) Born: 0582 (app) Born: 0584 Occup: Palace Mayor & Duke of Occup: Bishop of Metz Occup: Bishop of Metz Occup: Bishop of Metz and Saint Occup: Nun at Treves & Saint Sueve Died: 0611 (app) Died: 0611 (app) Died: 0640 Saint Arnulf of METZ Saint Doda of METZ Pepin I of LANDEN Itta of METZ Clodoule of METZ -

Annual Review 2008 Contents

Annual Review 2008 CONTENTS FOREWORDS . 3. MISSION . 4. VISION . 4. CORE VALUES . 5. ACKNOWLEDGING EXCELLENCE . 6. EMINENT VISITORS . 10 EXCHANGING IDEAS . 12 KNOWLEDGE SHARED . 14 SENSE OF PLACE . 17 INNOVATING AND INSPIRING . 20 PROFESSIONAL PARTNERS . 24 A SHARPER FOCUS . 26 IN PRINT . 28 STRENGTHENING LINKS . 30 THE BIGGER PICTURE . 32 THINKING GLOBALLY . 34 PUTTING SOMETHING BACK . 38 STUDENT AND GRADUATE LEADING LIGHTS . 40 STAFF MOVERS AND SHAKERS . 44 STIMULATING ENVIRONMENTS . 48 SENIOR STAFF . 50 FINANCIAL RESULts FOR THE YEAR ENDED 31ST JULY 2008 . 51 2 | University of Chester FOREWORDS Professor TJ Wheeler DL The Right Reverend Dr Peter Forster Vice-Chancellor and Principal Lord Bishop of Chester The Academic Year 2007-2008 has seen a massive growth in the President of the University Council and activities of the University, with developments in Research and Pro-Chancellor Knowledge Transfer being at the forefront of the University’s We continue to develop a range of activities and support concerns. The University has hosted a number of significant for business and our communities in Cheshire, Warrington, international conferences and has seen an impressive range of Chester and the North West. However, the international inaugural lectures, visiting speakers, together with its significant activities of the University continue to grow, as the participation in the Chester Literarature Festival. Staff of the University embraces fully the challenges and opportunities University continue to publish extensively and they have of globalisation. obtained a number of prestigious and competitive research contracts. As the University’s interests expand, it has put a The University’s history as an Anglican foundation is particular emphasis on partnership and on strengthening links demonstrated in many ways, the most obvious of which with its sister colleges in Cheshire. -

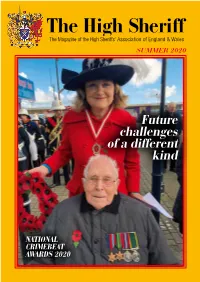

Future Challenges of a Different Kind

SUMMER 2020 Future challenges of a different kind NATIONAL CRIMEBEAT AWARDS 2020 www Lady Shrieval .antoniapugh-thom High Ant Haute dr ess Sheriffs onia for Coutur Pugh- as.co.uk eW omensw Thomas 020 ear 7731 7582 Photo courtesy of Harald Altmaier Volume 39 Issue 1 Summer 2020 The High Sheriffs’ Association of England and Wales President J R Avery Esq DL 12 15 Officers and Council 2020 OFFICERS Chairman The Hon H J H Tollemache Email [email protected] Honorary Secretary 34 38 J H A Williams Esq MBE Gatefield, Green Tye, Much Hadham Hertfordshire SG10 6JJ Tel 01279 842225 Email [email protected] Honorary Treasurer N R Savory Esq DL Thorpland Hall, Fakenham Norfolk NR21 0HD Tel 01328 862392 Email [email protected] COUNCIL Canon S E A Bowie DL T H Birch Reynardson Esq D C F Jones Esq DL J A T Lee Esq OBE DL Mrs V A Lloyd DL Mrs A J Parker JP DL Dr R Shah MBE JP DL Lt Col A S Tuggey CBE DL W A A Wells Esq TD (Hon Editor of The High Sheriff ) S J Young Esq MC JP DL The High Sheriff is published twice a year by Hall-McCartney Ltd for the High Sheriffs’ Association of England and Wales Hon Editor Andrew Wells Email [email protected] ISSN 1477-8548 ©2020 The High Sheriffs’ Association of England and Wales 4 From the Editor 12 General Election 44 Association regalia The Association is not as a body responsible for the opinions expressed and publications in The High Sheriff unless it is stated The ‘Red Mass’ that an article or a letter officially Diary 15 represents the Council’s views. -

Front Matter

TRANSACTIONS OF THE HISTORIC SOCIETY OF LANCASHIRE AND CHESHIRE VOLUME VIII. SESSION 1855-56. LONDON: J. H. PARKER, U77, STBAND. 1858. LIVEBPOOt : T. BIUKK1.L, PRINTER, TOOK BTREET. This Volume, like all the preceding ones, has been edited by the Honorary Secretary, under the direction of the Council. The writers of Papers, however, are alone responsible for the facts and opinions contained in their respective communications. DIRECTIONS TO THE BINDER. TO FACE PAGE PLATE I. Liverpool, shewing the ground built over ..................... 23 II. Boteler's Free Grammar School, Warrington .................. 62 III. The Master's House attached to Do............................... 68 IV. Geometrical Diagrams ............................................... 80 V. Map of Babylon............ ............................................ 94 VI. Map of Walton-le-Dale and Neighbourhood .................. 127 VII. (Marked A) Eoman Eemains ....................................... 130 VIII. (Marked B) Eoman Pottery.......................................... 131 IX. (Marked C) Eoman Pottery ....................................... 132 X. Diseased Peart views of ............................................. 195 '- Tables, folded and in sheet, in their order, after page 216. XI. (Marked M) to follow Table II. XII. (Marked N) | between Table III, 1855, and Table III, Means XIII. (Marked O) j for 1852, '3, '4, '5. XIV. (Marked P) to face Tables IV and V. XV.^-(Marked Q) to face Table VIII. XVI. Enamelled Gold Watch............................................. 222 EXPLANATOBY NOTE. Of the Sixteen illustrations contained in this volume, only eight have been produced wholly at the cost of the Society. These are I, IV, V, VI, VII, VIII, IX, X. Nos. II and III were presented complete, by Mr. Marsh, in illustration of his own paper. No. XVI was in like manner presented complete, by the Rev. John James Moss, M.A., in illustration of his own remarks on Watches. -

An Account of the Ancient Town of Frodsham In

This is a reproduction of a library book that was digitized by Google as part of an ongoing effort to preserve the information in books and make it universally accessible. https://books.google.com Harvard College Library ) ACADEMIAE SIGILLUM RO INV.NO FROM THE GIFT OF WILLIAM ENDICOTT , JR . ( Class of 1887 ) OF BOSTON هت AN ACCOUNT OF THE ANCIENT TOWN OF FRODSHAM , IN CHESHIRE . All only for to publish plaine Tyme past , tyme present , bothe , That tyme to come may well retaine Of each good tyme the truthe . BY WILLIAM BEAMONT . WARRINGTON : PERCIVAL PEARSE , 8 , SANKEY STREET . I 88 1 . Pr 5184.68 HARVARD COLLEGE JUN 14 1918 LIBRARY biti Price ca pe eman TO THE Reverend Henry Birdwood Blogg , M.A. , VICAR OF FRODSHAM ( The 42nd in succession to that office ) , WHO , WHILE FAITHFULLY DISCHARGING HIS SPIRITUAL DUTIES , SUGGESTED , AND BY THE LIBERAL CONTRIBUTIONS OF HIS PARISHIONERS AND OTHERS , CARRIED OUT THE DESIGN OF RESTORING THE ORIGINAL FEATURES WHICH HIS VENERABLE PARISH CHURCH HAD RECEIVED FROM ITS FOUNDER IN THE NINTH CENTURY , BUT WHICH TIME AND INJUDICIOUS REPAIRS HAD GREATLY OBSCURED , THIS BOOK IS RESPECTFULLY DEDICATED BY Its Author . Orford Hall , September 19th , 1881 . FRODSHAM : SOME ACCOUNT OF ITS HISTORY . CHAPTER I. BEFORE THE NORMAN CONQUEST . FRODSHAM , though a very ancient market town , with a weekly 1 market and two fairs yearly , and once an important pass defending the entrance into Cheshire from the west , has lost , or perhaps more properly may be said to have gained , by the change to more peaceful times , some of its former importance . -

Awards for Enterprise 2 015/16

The High Sheriff’s Awards for Enterprise 2 015/16 Guide for businesses entering the Awards Celebrating 10 years of the High Sheriff’s Awards for Enterprise ANNIVER TH SA N R E Y T H in partnership with S IG th D 1H 0 R S A H W ERIFF’S A Welcome to the 10th Annual High Sheriff’s Awards Categories and Criteria Awards for Enterprise 2015/16 High Sheriff’s Award for Enterprise 2015/16, Entrants must be based in Cheshire West and Cheshire, Cheshire East, sponsored by Cheshire & Warrington LEP, Halton or Warrington, have an annual turnover of between £500,000 O2 and ESL Fuels and £25m, employ between 5-250 (fte) members of staff, and I’m thrilled to be High Sheriff of Cheshire this year presiding over the demonstrate outstanding performance and explain their strategy to 10th Anniversary celebrations of the High Sheriff’s Awards for Enterprise, Win a place for an appropriately qualified ensure that the company will continue to expand and flourish in Cheshire’s prime business awards event. manager on the University of Chester’s MBA the future. programme worth £10,000 Organisations that have achieved outstanding Award for Training, Development These Awards were introduced in 2006 by the then High Sheriff of Cheshire, commercial success and sustainable growth will and Opportunity for Young David Briggs MBE, to recognise outstanding achievement by enterprises in be honoured with this prestigious award. They People, sponsored by Cheshire Cheshire, Halton and Warrington. Every year the Awards have gone from will have a need to develop the company’s East and Click Consult strength to strength and this year I’m pleased to introduce a new category management skills and a manager destined to ‘Award for Training, Development and Opportunity for Young People’. -

A Brief of a Lineage of the Very Ancient Family and Surname of Shallcross

H Brief OF A LINEAGE, ETC. BY William Henry Shawcross, Vicar of Bretforton. A BRIEF OF A LINEAGE OF THE VERY ANCIENT FAMILYAND SURNAME OF SHALLCROSS, OR SHAWCROSS, OF THAT MANOR, IN THE HIGH PEAK, CO. DERBY; ILLUSTRATING TO THE MEMORYOF POSTERITY THE CONNECTION OF THAT HOUSE WITH EQUESTRIAN, NOBLE, AND ROYAL FAMILIES; ATTEMPTED, MDCCCXCVL, INCOMPLETELY, A SCION OF THE FAMILY. <- EVESHAM: KNAPTON AND MAYER. 1896. V'Priee $8. 6d, A IX. 9- 9.45^3 /$¦ PREFACE. "Iwi3h that they who really have blood," observes Boswell, "would be more careful to trace and ascertain its coarse." The House before us is of historic and eminent \ has had its part in our Island story, and is still thus happily distinguished in its descendants. The preservation of this epitome of its genealogy; a breviate which is itself the essence of copious notes ;jieeds therefore no apology. The direct and cadet descents of this ancient Derbyshire House are traced herein from the Cartse Antiquse in the British Museum, Ormerod, Jewitt, Glover, Earwaker, Burke, Foster, and nearly 100 other genealogical authorities. We find the family patronymic written in at least 38 different ways inthese records ;the variations of ShaiiLCßoss, orof Shawcross, being more usually adopted. ' There is authority for each spelling of the surname as it occurs. | For convenience in making notes the alternate pages are (left blank. 28 Nov. 1896. f@*ral*ff 3fno%ttfo» anno 17th Edwabd 111., a.d. 1342 ; Gules, a saltire, argent, between four annulets of the second. &•> Crests :(1.) anno 3rd Eiohard 11., a.d. 1379, A cross, patte"e fitche"e, gules ; and (2.) at the same date, Amartlet, argent, holding in the beak a Gross patte*e fitche'e, gules. -

Being the Transactions of the Lodge Quatuor Coronati, No. 2076, London

H E L I , . T B I, , "^M YOUNG UN, PhDiograTure by Annan Glasgow Pram aPhalographhy Stephen Share FRP. 3. London V .Sa ^C Mkfg 3|K- latior €oroEatoram BEING THE TRANSACTIONS of the QUATUOR CORONATI LODGE NO. 2076. LONDON. -*- -^ * -*- n^ . A r* :i?=^a FROM THE ISABELLA MISSAL BRITISH MUSEUM ADD. MSS., 18,851 CIRCA 1600 A.D. D=^ rD EDITED FOR THE COMMITTEE BT COLONEL F. M. RICKARD, P.G.S.B. VOLUME L. W. J. Parrett, Ltd., Printers. Margate. 1940. THE LI BRART liKlGHAM YOUNG U IV^i^SflTT fROyO, UTAH TABLE OF CONTENTS LODGE PROCEEDINGS. PAGE. Friday, 1st January, 1937 1 Friday, 5th March, 1937 30 Friday, 7th May, 1937 92 Summer Outing: East "Warwickshire, Thursday, 17th June, to Sunday, 20th June, 1937 133 Thursday, 24th June, 1937 143 Friday, 1st October, 1937 187 Monday, 8th November, 1937 211 NOTES AND QUERIES. Lelande-Locke MS. 128 OBITUARY. Achard, W. 0. 129 Baird, H. 129 Baldwyn, F. J. 129 Bent, T. 129 Bishop, J. H. 129 Blackmore, T. H. 129 Boutell, F. H. 129 Braine, C. W. 129 Brooke-Pechell, Sir A. A. 227 Browse, H. W. J. 129 Caldwell, J. 227 Cass, A. 129 Chapman, J. 129 Childe, Bcv. Canon C. V. 129 Collins, G. L. 130 Cook, J. 130 Crump, Dr. C. H. 227 de Lafontaine, H. T. C. 227 Earle, Dr. J. H. 227 Emery, G. E. 130 Ensor, A. J. 130 Evans, T. 227 Findlay, M. F. 130 Fishel, J. ... 130 Gilliland, W. E. 227 Gilmour, P. G. 130 Gordon, A. T. 227 Gould, J. -

Sharples Scoops Top Business Award

Issue 3 Spring 2016 scoop welcome... With nearly 40 years in business we have built up a wealth of experience here at Sharples Group. The last decade has certainly been fast paced and we are very proud of our team’s ability to keep up with the office equipment landscape and ever changing Sharples scoops top requirements of our customers. With our people in mind business award we have concentrated the last 12 months on soft skills development, releasing the potential within our workforce and Sharples Group fought off strong enhancing our values competition from Chester Zoo, Jodrell based culture. Bank and others to win the High Sheriff’s 2016 award for responsible business It has also been a year of practice. awards which we hope is seen as substantiation The announcement was made to 400 guests of how we differ from at the High Sheriff of Cheshire’s Enterprise our competitors and Awards at Chester Racecourse. Sharples MD we believe that people Mark Brocklehurst said: “I’m delighted. This development is the award speaks volumes about us and the way best way to create the we do business.” £500,000 for North West charities; as a best possible customer carbon zero accredited company, funding experience. Sharples will be celebrating its 40th over 680 energy efficient stoves for families anniversary next year and we’re proud of in Kenya; supplying two local schools with We hope you enjoy this our track record for responsible and ethical ground-breaking eco-friendly copiers with newsletter. business. We care passionately about our impact on customers, the community, erasable toner, so pupils and staff can re-use David Griffiths, Director environment and our own staff. -

0 Lancashire PGM Abridged

The Five PGMs of Lancashire 1734 to 1826 By: Eddie Forkgen As early as 1661 the influential London based Royal Society requested a former Society President and a freemason of 20 years standing to write the history of Freemasonry. Also Dr. Francis Drake, a Grand Master of the Grand Lodge of All England at York in 1767 and a member of the Royal Society and who it is also thought to have also submitted a written history of Freemasonry, Both documents seems to have been mislaid during the time when the Duke of Sussex was President of the Royal Society (1830-38). We know that freemasonry was active in Lancashire in the 17th century, as Elias Ashmole recorded in his diary the fact that he was initiated into a Lodge in Warrington in 1646. We also have a number of “Old Masonic Charges” which were written in the 1600’s such as the Colne and the Beswicke MS’s, all of which demonstrates that Lancashire has a rich Masonic heritage. At the beginning of the 18th Century the first Grand Lodge was formed by middle to upper- class freemasons from four London and Westminster lodges, following the departure of the many operative masons from the Capital on the completion of the many building projects following the Great Fire of London. In the first few years of the Grand Lodge the Grand Masters were elected on an annual basis. The third Grand Master, the Revd. Dr. Desaguliers and the 5th Grand Master the Duke of Montagu were both active Fellows of the Royal Society, as were many of the Grand Masters that followed.