Ecomusicology: Bridging the Sciences, Arts, and Humanities

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Black US Army Bands and Their Bandmasters in World War I

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Faculty Publications: School of Music Music, School of Fall 8-21-2012 Black US Army Bands and Their Bandmasters in World War I Peter M. Lefferts University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/musicfacpub Part of the Music Commons Lefferts, Peter M., "Black US Army Bands and Their Bandmasters in World War I" (2012). Faculty Publications: School of Music. 25. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/musicfacpub/25 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Music, School of at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications: School of Music by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. 1 Version of 08/21/2012 This essay is a work in progress. It was uploaded for the first time in August 2012, and the present document is the first version. The author welcomes comments, additions, and corrections ([email protected]). Black US Army bands and their bandmasters in World War I Peter M. Lefferts This essay sketches the story of the bands and bandmasters of the twenty seven new black army regiments which served in the U.S. Army in World War I. They underwent rapid mobilization and demobilization over 1917-1919, and were for the most part unconnected by personnel or traditions to the long-established bands of the four black regular U.S. Army regiments that preceded them and continued to serve after them. Pressed to find sufficient numbers of willing and able black band leaders, the army turned to schools and the entertainment industry for the necessary talent. -

MU/AAS 1103 Co

MISSISSIPPI STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF EDUCATION DEPARTMENT of MUSIC COURSE SYLLABUS Course Prefix and Number: MU/AAS 1103 Course Title: African American Music Credit hours: Three (3) semester hours Type of Course: Lecture Catalog Description : Three hours lecture. A study of African musical and cultural traditions with focus on the impact of these traditions on the development and advancement of African-American music. College of Education Conceptual Framework: The faculty in the College of Education at Mississippi State University are committed to assuring the success of students and graduates by providing superior learning opportunities that are continually improved as society, schools, and technology change. The organizing theme for the conceptual framework for the College of Education at Mississippi State University is educational professionals - dedicated to continual improvement of all students’ educational experiences. The beliefs that guide program development are as follows: 1. KNOWLEDGE - Educational professionals must have a deep understanding of the organizing concepts, processes, and attitudes that comprise their chosen disciplinary knowledge base, the pedagogical knowledge base, and the pedagogical content knowledge base. They must also know how to complement these knowledge bases with the appropriate use of technology. 2. COLLABORATION - Educational professionals must continually seek opportunities to work together, learn from one another, forge partnerships, and assume positions of responsibility. 3. REFLECTION - Educational professionals must be willing to assess their own strengths and weaknesses through reflection. They must also possess the skills, behaviors, and attitudes necessary to learn, change, and grow as life-long learners. 4. PRACTICE - Educational professionals must have a rich repertoire of research-based strategies for instruction, assessment, and the use of technologies. -

Understanding the Causes and Effects of Regional Orchestra Bankruptcies in the San Francisco Bay Area

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Santa Barbara Breakdown on the Freeway Philharmonic: Understanding the Causes and EFFects oF Regional Orchestra Bankruptcies in the San Francisco Bay Area A dissertation submitted in partial satisFaction oF the requirements for the degree Doctor oF Philosophy in Music by Alicia Garden Mastromonaco Committee in charge: ProFessor Derek Katz, Chair ProFessor SteFanie Tcharos ProFessor Martha Sprigge December 2020 The dissertation oF Alicia Garden Mastromonaco is approved. _____________________________________________ Martha Sprigge _____________________________________________ SteFanie Tcharos _____________________________________________ Derek Katz, Committee Chair December 2020 Breakdown on the Freeway Philharmonic: Understanding the Causes and EFFects oF Regional Orchestra Bankruptcies in the San Francisco Bay Area Copyright © 2020 by Alicia Garden Mastromonaco iii DEDICATION I dedicate this dissertation to my Friends and colleagues in the Bay Area orchestral world, the Freeway Philharmonic musicians. I hope that this project might help us keep our beloved musical spaces for a long time to come. iv ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I must first acknowledge my advisor Derek, without whose mentorship this project likely would not have existed. He encouraged me to write about small regional orchestras in the Bay Area and saw the kernel oF what this project would become even beFore I did. His consistent support and endless knowledge on closely related topics shaped nearly every page oF this dissertation. I am also grateFul to SteFanie Tcharos and Martha Sprigge, who have inspired me in their rigorous approach in writing, and who have shaped this dissertation in many ways. This project was borne out oF my own experiences as a musician in the Bay Area orchestral world over the last fourteen years. -

Music and Environment: Registering Contemporary Convergences

JOURNAL OF OF RESEARCH ONLINE MusicA JOURNALA JOURNALOF THE MUSIC OF MUSICAUSTRALIA COUNCIL OF AUSTRALIA ■ Music and Environment: Registering Contemporary Convergences Introduction H O L L I S T A Y L O R & From the ancient Greek’s harmony of the spheres (Pont 2004) to a first millennium ANDREW HURLEY Babylonian treatise on birdsong (Lambert 1970), from the thirteenth-century round ‘Sumer Is Icumen In’ to Handel’s Water Music (Suites HWV 348–50, 1717), and ■ Faculty of Arts Macquarie University from Beethoven’s Pastoral Symphony (No. 6 in F major, Op. 68, 1808) to Randy North Ryde 2109 Newman’s ‘Burn On’ (Newman 1972), musicians of all stripes have long linked ‘music’ New South Wales Australia and ‘environment’. However, this gloss fails to capture the scope of recent activity by musicians and musicologists who are engaging with topics, concepts, and issues [email protected] ■ relating to the environment. Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences University of Technology Sydney Despite musicology’s historical preoccupation with autonomy, our register of musico- PO Box 123 Broadway 2007 environmental convergences indicates that the discipline is undergoing a sea change — New South Wales one underpinned in particular by the1980s and early 1990s work of New Musicologists Australia like Joseph Kerman, Susan McClary, Lawrence Kramer, and Philip Bohlman. Their [email protected] challenges to the belief that music is essentially self-referential provoked a shift in the discipline, prompting interdisciplinary partnerships to be struck and methodologies to be rethought. Much initial activity focused on the role that politics, gender, and identity play in music. -

Encyclopedia of African American Music Advisory Board

Encyclopedia of African American Music Advisory Board James Abbington, DMA Associate Professor of Church Music and Worship Candler School of Theology, Emory University William C. Banfield, DMA Professor of Africana Studies, Music, and Society Berklee College of Music Johann Buis, DA Associate Professor of Music History Wheaton College Eileen M. Hayes, PhD Associate Professor of Ethnomusicology College of Music, University of North Texas Cheryl L. Keyes, PhD Professor of Ethnomusicology University of California, Los Angeles Portia K. Maultsby, PhD Professor of Folklore and Ethnomusicology Director of the Archives of African American Music and Culture Indiana University, Bloomington Ingrid Monson, PhD Quincy Jones Professor of African American Music Harvard University Guthrie P. Ramsey, Jr., PhD Edmund J. and Louise W. Kahn Term Professor of Music University of Pennsylvania Encyclopedia of African American Music Volume 1: A–G Emmett G. Price III, Executive Editor Tammy L. Kernodle and Horace J. Maxile, Jr., Associate Editors Copyright 2011 by Emmett G. Price III, Tammy L. Kernodle, and Horace J. Maxile, Jr. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, except for the inclusion of brief quotations in a review, without prior permission in writing from the publisher. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Encyclopedia of African American music / Emmett G. Price III, executive editor ; Tammy L. Kernodle and Horace J. Maxile, Jr., associate editors. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-313-34199-1 (set hard copy : alk. -

The Introduction of the Black Conductor Akeila Thomas; Faculty Sponsor: Dr

The Introduction of the Black Conductor Akeila thomas; Faculty Sponsor: Dr. Jamie Weaver The conductor has become a position of great influence and necessity to the performing ensemble due to innovations in performance between the Baroque and mid to late Romantic periods. With such prominence given to the title, one such conductor has gained very little mention throughout the course of music's history. African-American musicians have played such a catalytic role in the shape and progression of Western music. Thorough research demonstrates that general knowledge of the influence of black conductors has developed slowly and has been largely overlooked. My research was conducted to determine the importance of the black conductor and his contribution to American music. • I narrowed my focus to the four genres that were the most prominent in America during the early to mid 20th century: The Symphony, Jazz, The Negro Spiritual and Opera. • I researched the lives, compositions and accomplishments of conductors William Grant Still, Duke Ellington, Anton Armstrong, and Henry Lewis. These conductors were the most influential African-Americans in these genres. • I studied the scores, listened to recordings and watched performances of their works in order to gain a more personal view of their ideals in music. http://www.controappuntoblog.org/2012/03/15/william-grant-still-1895-1978/ http://everyguyed.com/lookbook/style-icon-jazz-musicians http:/du/m/www.baylor.eediacommunications/news.php?action=story&story=38383 http://africlassical.blogspot.com/2012/04/john-malveaux-african-american.html • My research allowed me to see that the black conductor is specific only to American music genres. -

LUNDY-DISSERTATION-2015.Pdf (676.0Kb)

© Copyright by Georgianne Lundy December, 2015 AN ETHNOGRAPHIC CASE STUDY OF ORCHESTRA DIRECTORS AT HISTORICALLY BLACK COLLEGES AND UNIVERSITIES ____________________ A Dissertation Presented to The Faculty of the Moores School of Music University of Houston ____________________ In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Music Arts ____________________ By Georgianne Lundy December, 2015 AN ETHNOGRAPHIC CASE STUDY OF ORCHESTRA DIRECTORS AT HISTORICALLY BLACK COLLEGES AND UNIVERSITIES _____________________ An Abstract of a Dissertation Presented to The Faculty of the Moores School of Music University of Houston ____________________ In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Musical Arts ____________________ By Georgianne Lundy December, 2015 ABSTRACT The purpose of this ethnographic study is to explore the experiences of orchestra directors at Historically Black Colleges and Universities (HBCUs). While there have been a few studies regarding African American orchestra students in public schools, I am unaware of research that has explored these college level ensembles from the perspective of their directors. Critical Race Theory (CRT) was used as a theoretical framework for this study. Specifically, this study sought to answer the following research questions: (a) What are the experiences of orchestra directors at HBCUs? (b) What are the challenges faced by HBCU orchestra directors, and how do they address them? and (c) How do HBCU orchestra directors describe their successes? I chose five participants based on their reputations as successful directors. Data collection included audio-recordings of semi-structured interviews and observations of the directors at their respective campuses. Data were coded and analyzed for emerging themes, and trustworthiness was ensured through member checks, peer review, and data triangulation. -

Reference Books Classical the New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians, 20 Vols

LSC - Montgomery Library 3200 College Park Dr. Bldg. F Music Conroe, TX 77384 http://www.lonestar.edu/library 936-273-7390 Reference Books Classical The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians, 20 vols. REF ML 100.N48 2001 Penguin Companion to Classical Music REF ML 102 .C53 G75 2006 Encyclopedia of the Piano REF ML 102.P5E53 1996 Baker’s Biographical Dictionary of Musicians REF ML 105.B16 1992 The Harvard Biographical Dictionary of Music REF ML 105.H38 1996 The Norton/Grove Dictionary of Women Composers REF ML 105.N66 1994 Baker’s Biographical Dictionary of Twentieth Century Classical Musicians REF ML 105.S612 1997 Dictionary of American Classical Composers REF ML 106 .U3 B87 2005 Musical Terminology: A Practical Compendium in Four Languages REF ML 108.B55 1999 Musical Terms, Symbols and Theory REF ML 108.T46 1989 A History of Western Music REF ML 160.G87 2001 Oxford History of Western Music REF ML 160.T18 2005 Music Since 1900 REF ML 197.S634 1994 Black Conductors REF ML 402.H36 1995 Jazz and Blues Encyclopedia of the Blues REF ML 102 .B6E53 2006 Jazz: The Rough Guide REF ML 102.J3C325 1995 The New Grove Dictionary of Jazz, 3 vols. REF ML 102.J3N48 2002 Encyclopedia of Rhythm & Blues and Doo-Wop Vocal Groups REF ML 102.P66R67 2000 The Blackwell Guide to Recorded Jazz REF ML 156.4.J3B66 1996 The Oxford Companion to Jazz REF ML 3507.O94 2000 The Blues: From Robert Johnson to Robert Cray REF ML 3521.R87 1997 Opera and Theatre Gänzl’s Book of the Musical Theatre REF MT 95.G2 1989 The Encyclopedia of the Musical Theatre, 3 vols. -

Journal of the Conductors Guild

Journal of the Conductors Guild Volume 29, Numbers 1 & 2 2009 719 Twinridge Lane Table of Contents Richmond, VA 23235-5270 T: (804) 553-1378; F: (804) 553-1876 E-mail: [email protected] [email protected] Maestro Dean Dixon page 1 Website: www.conductorsguild.org . Advancing the Art and Profession (1915-1976): A Forgotten Officers American Conductor by Rufus Jones, Jr. D.M.A. Michael Griffith, President John Farrer, Secretary James Allen Anderson, President-Elect Lawrence J. Fried, Treasurer Gordon J. Johnson, Vice-President Sandra Dackow, Past President Visionary Leadership and the page 6 Board of Directors Conductor Ira Abrams Claire Fox Hillard Lyn Schenbeck by Nancy K. Klein, Ph.D. Leonard Atherton Paula K. Holcomb Michael Shapiro Christopher Blair Rufus Jones, Jr.* Jonathan Sternberg* David Bowden John Koshak Kate Tamarkin Creating a Fresh Approach to page 12 John Boyd Anthony LaGruth Harold Weller Conducting Gesture Jeffrey Carter Peter Ettrup Larsen Kenneth Woods by Charles L. Gambetta, D.M.A. Stephen Czarkowski Brenda Lynne Leach Amanda Winger* Charles Dickerson III David Leibowitz* Burton A. Zipser* Kimo Furumoto Lucy Manning *ex officio Mussorgsky/Ravel’s Pictures at an page 31 Jonathan D. Green Michael Mishra Exhibition : Faithful to the Wrong Earl Groner John Gordon Ross Source by Jason Brame Advisory Council Pierre Boulez Tonu Kalam Maurice Peress Emily Freeman Brown Wes Kenney Donald Portnoy Score and Parts: Maurice page 43 Michael Charry Daniel Lewis Barbara Schubert Ravel’s Bolero Harold Farberman Larry Newland Gunther Schuller by Clinton F. Nieweg and Nancy M. Adrian Gnam Harlan D. Parker Leonard Slatkin Bradburd Samuel Jones Theodore Thomas Award Winners Claudio Abbado Frederick Fennell Leonard Slatkin Maurice Abravanel Margaret Hillis Esa-Pekka Salonen Marin Alsop James Levine Sir Georg Solti Leon Barzin Kurt Masur Michael Tilson Thomas Leonard Bernstein Max Rudolf David Zinman Pierre Boulez Robert Shaw Thelma A. -

Grappling with Donald Jay Grout's

Grappling with Donald Jay Grout’s Essays on Music Historiography KRISTY JOHNS SWIFT have finally gotten A History of Western Music adopted. I would not be surprised if it has driven all other music history texts off the shelves,”1 I wrote Rey Longyear to Donald Jay Grout in a letter dated 7 May 1961. Grout replied that his book “did pretty well its first year. It now remains to be seen how well it will hold up.”2 A History of Western Music (HWM hereafter), received favorable reviews fifty years ago in the United States and England, despite complaints about content, mostly omissions of particular composers, compositions, and styles. Nineteen published reviews and numerous informal endorsements from university music history teachers of the first three edi- tions (and also a shorter edition) bear witness to the success of these early Earlier versions of this paper were presented at the American Musicological Society, Mid- west Chapter meeting (25 April 2009, Baldwin-Wallace College, Berea, Ohio), the Music Theory-Musicology Society Conference (9 April 2010, University of Cincinnati College- Conservatory of Music, Cincinnati, Ohio), and the Midwest Graduate Music Consortium Conference (16 April 2010, University of Chicago, Chicago, Illinois). The material is drawn from my forthcoming PhD dissertation, “Donald J. Grout, Claude V. Palisca, and J. Peter Burkholder’s A History of Western Music, 1960–2009: Getting the Story Crooked,” at the Uni- versity of Cincinnati College-Conservatory of Music. A Theodore Presser Music Award made much of the research for this paper possible. I would like to thank Dr. Richard Boursy and Emily Ferrigno at Yale University’s Irving S. -

Directed by Sharon Lewis Produced by Iron Bay Media

DISRUPTOR CONDUCTOR DIRECTED BY SHARON LEWIS PRODUCED BY IRON BAY MEDIA FOR MORE INFORMATION Noreen Hamid - Publicist [email protected] 647.404.8496 FILM SYNOPSIS Daniel Bartholomew-Poyser is an unlikely hero on a mission to create live orchestral shows that aren't just for the rich and fancy. Daniel Bartholomew-Poyser is one of the first openly gay black conductors in Canada. The child of a working-class Caribbean single mother, he was raised in Calgary, Alberta and he understands what it is to be an ‘other’. As he struggled with his sexuality, Bartholomew-Poyser turned to music for solace and finally found his voice as a conductor. He believes that the beauty and grace of music can unite and uplight all of us beyond race, class and gender barriers. Bartholomew-Poyser wants to use his musical power for good. In Disruptor, Conductor we see him on a mission to break down institutional walls and bring live orchestral music to millennials, people of colour, young people, LGBTQ, prisoners, refugees, students; anyone who identifies as ‘different’. “We're trying to bring music to everybody. Often times, when you heard these instruments, sometimes you had to go to a concert hall to hear it. We're trying to bring it out of the concert hall and just take it to wherever people are,” says Bartholomew-Poyser. Along with RuPaul’s Drag Race star, Thorgy Thor, Bartholomew-Poyser creates the first orchestral drag queen show in Canada. It’s a way to express all parts of himself at once; bringing old-world orchestra and his recently-discovered LGBTQ community together in harmonic union. -

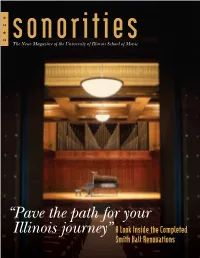

“Pave the Path for Your Illinois Journey”

2020 sonorities The News Magazine of the University of Illinois School of Music “Pave the path for your Illinois journey” A Look Inside the Completed Smith Hall Renovations Dear Friends of the School of Music, Published for the alumni and friends of the School of Music at the University of Illinois at he 2019/20 academic year is my first as director of the school Urbana-Champaign. and as a member of the faculty, and in my short tenure, I’ve The School of Music is a unit of the College of been repeatedly astonished by the depth and breadth of the Fine + Applied Arts and has been an accredited world-class music programs that have been built here. From institutional member of the National Association T of Schools of Music since 1933. our Lyric Theatre program to our symphony orchestra, from the Kevin Hamilton, Dean of the College of Fine + Black Chorus to the Experimental Music Studios, from the award-winning research Applied Arts being conducted in musicology and music education to the spirited performances Jeffrey Sposato, Director of the School of Music of the Marching Illini, the students and faculty at Illinois are second to none. It’s a true honor and privilege to join them! Michael Siletti, Editor Illinois graduates play leading roles in hundreds of orchestras, choruses, bands, Jessica Buford, Copy Editor K–12 schools, and colleges and universities. The School of Music is first and foremost Design and layout by Studio 2D a resource for the state of Illinois, but our students and faculty come from around Cover photograph by Michael Siletti the world, and the impact of our alumni and faculty is global as well.