Milky Way; Not Just a Delicious Candy Anymore…

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ngc Catalogue Ngc Catalogue

NGC CATALOGUE NGC CATALOGUE 1 NGC CATALOGUE Object # Common Name Type Constellation Magnitude RA Dec NGC 1 - Galaxy Pegasus 12.9 00:07:16 27:42:32 NGC 2 - Galaxy Pegasus 14.2 00:07:17 27:40:43 NGC 3 - Galaxy Pisces 13.3 00:07:17 08:18:05 NGC 4 - Galaxy Pisces 15.8 00:07:24 08:22:26 NGC 5 - Galaxy Andromeda 13.3 00:07:49 35:21:46 NGC 6 NGC 20 Galaxy Andromeda 13.1 00:09:33 33:18:32 NGC 7 - Galaxy Sculptor 13.9 00:08:21 -29:54:59 NGC 8 - Double Star Pegasus - 00:08:45 23:50:19 NGC 9 - Galaxy Pegasus 13.5 00:08:54 23:49:04 NGC 10 - Galaxy Sculptor 12.5 00:08:34 -33:51:28 NGC 11 - Galaxy Andromeda 13.7 00:08:42 37:26:53 NGC 12 - Galaxy Pisces 13.1 00:08:45 04:36:44 NGC 13 - Galaxy Andromeda 13.2 00:08:48 33:25:59 NGC 14 - Galaxy Pegasus 12.1 00:08:46 15:48:57 NGC 15 - Galaxy Pegasus 13.8 00:09:02 21:37:30 NGC 16 - Galaxy Pegasus 12.0 00:09:04 27:43:48 NGC 17 NGC 34 Galaxy Cetus 14.4 00:11:07 -12:06:28 NGC 18 - Double Star Pegasus - 00:09:23 27:43:56 NGC 19 - Galaxy Andromeda 13.3 00:10:41 32:58:58 NGC 20 See NGC 6 Galaxy Andromeda 13.1 00:09:33 33:18:32 NGC 21 NGC 29 Galaxy Andromeda 12.7 00:10:47 33:21:07 NGC 22 - Galaxy Pegasus 13.6 00:09:48 27:49:58 NGC 23 - Galaxy Pegasus 12.0 00:09:53 25:55:26 NGC 24 - Galaxy Sculptor 11.6 00:09:56 -24:57:52 NGC 25 - Galaxy Phoenix 13.0 00:09:59 -57:01:13 NGC 26 - Galaxy Pegasus 12.9 00:10:26 25:49:56 NGC 27 - Galaxy Andromeda 13.5 00:10:33 28:59:49 NGC 28 - Galaxy Phoenix 13.8 00:10:25 -56:59:20 NGC 29 See NGC 21 Galaxy Andromeda 12.7 00:10:47 33:21:07 NGC 30 - Double Star Pegasus - 00:10:51 21:58:39 -

![Arxiv:1803.10763V1 [Astro-Ph.GA] 28 Mar 2018](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/1474/arxiv-1803-10763v1-astro-ph-ga-28-mar-2018-2151474.webp)

Arxiv:1803.10763V1 [Astro-Ph.GA] 28 Mar 2018

Draft version October 10, 2018 Typeset using LATEX default style in AASTeX61 TRACERS OF STELLAR MASS-LOSS - II. MID-IR COLORS AND SURFACE BRIGHTNESS FLUCTUATIONS Rosa A. Gonzalez-L´ opezlira´ 1 1Instituto de Radioastronomia y Astrofisica, UNAM, Campus Morelia, Michoacan, Mexico, C.P. 58089 (Received 2017 October 20; Revised 2018 February 20; Accepted 2018 February 21) Submitted to ApJ ABSTRACT I present integrated colors and surface brightness fluctuation magnitudes in the mid-IR, derived from stellar popula- tion synthesis models that include the effects of the dusty envelopes around thermally pulsing asymptotic giant branch (TP-AGB) stars. The models are based on the Bruzual & Charlot CB∗ isochrones; they are single-burst, range in age from a few Myr to 14 Gyr, and comprise metallicities between Z = 0.0001 and Z = 0.04. I compare these models to mid-IR data of AGB stars and star clusters in the Magellanic Clouds, and study the effects of varying self-consistently the mass-loss rate, the stellar parameters, and the output spectra of the stars plus their dusty envelopes. I find that models with a higher than fiducial mass-loss rate are needed to fit the mid-IR colors of \extreme" single AGB stars in the Large Magellanic Cloud. Surface brightness fluctuation magnitudes are quite sensitive to metallicity for 4.5 µm and longer wavelengths at all stellar population ages, and powerful diagnostics of mass-loss rate in the TP-AGB for intermediater-age populations, between 100 Myr and 2-3 Gyr. Keywords: stars: AGB and post{AGB | stars: mass-loss | Magellanic Clouds | infrared: stars | stars: evolution | galaxies: stellar content arXiv:1803.10763v1 [astro-ph.GA] 28 Mar 2018 Corresponding author: Rosa A. -

Master Astronomer Program

MASTER ASTRONOMER PROGRAM 2019 Program Handbook by Zach Schierl and Leesa Ricci Cedar Breaks National Monument National Park Service i Table of Contents Section 1: About the Master Astronomer Program Section 2: Astronomy & the Night Sky 2.1 Light 2.2 Celestial Motions 2.3 History of Astronomy 2.4 Telescopes & Observatories 2.5 The Cosmic Cast of Characters 2.6 Our Solar System 2.7 Stars 2.8 Constellations 2.9 Extrasolar Planets Section 3: Protecting the Night Sky 3.1 Introduction to Light Pollution 3.2 Why Protect the Night Sky? 3.3 Measuring and Monitoring Light at Night 3.4 Dark-Sky Friendly Lighting Section 4: Sharing the Night Sky 4.1 Using a Telescope 4.2 Communicating Astronomy & the Importance of Dark Skies to the Public Appendices: A. Glossary of Terms B. General Astronomy Resources C. Acknowledgements D. Endnotes & Works Cited 1 SECTION 1: ABOUT THE MASTER ASTRONOMER PROGRAM 3 Section 1: About the Master Astronomer Program WELCOME TO THE MASTER ASTRONOMER PROGRAM All of us at Cedar Breaks National Monument are glad that you are excited to learn more about astronomy, the night sky, and dark sky stewardship. In addition to learning about these topics, we also hope to empower you to share your newfound knowledge with your friends, family, and neighbors, so that all residents of Southern Utah can enjoy our beautiful dark night skies. The Master Astronomer Program is an interactive, hands-on, 40-hour workshop developed by Cedar Breaks National Monument that weaves together themes of astronomy, telescopes, dark sky stewardship, and science communication. -

Resolucion Hcd N° 67/00

Universidad Nacional de Córdoba FACULTAD DE MATEMÁTICA ASTRONOMÍA Y FÍSICA UNIVERSIDAD NACIONAL DE CÓRDOBA Facultad de Matemática, Astronomía y Física PROGRAMA DE CURSO DE POSGRADO TÍTULO: Propiedades astrofísicas de galaxias enanas: el Sistema Magallánico AÑO: 2018 CUATRIMESTRE: Segundo CARGA HORARIA: 60 hs. No. DE CRÉDITOS: CARRERA/S: Astronomía DOCENTE ENCARGADO: Andrés Eduardo Piatti PROGRAMA I. Estructura y dimensiones de las galaxias Descripción de diferentes indicadores de distancia. El clump de las gigantes rojas: justificación y uso como indicador de distancia. Conteos estelares: descripción de diferentes técnicas, utilización y alcance. Relevamientos fotométricos. Descripción de las estructuras observadas en las galaxias. Ajustes de perfiles de densidad estelar. Efectos de proyección espacial de las galaxias. II. El puente Magallánico y el Leading Arm Descripción de evidencias observacionales. Características. Trazabilidad del puente: diferentes indicadores. Dimensiones del puente. Poblaciones estelares: edad, metalicidad. Origen del puente. III. Dinámica de las galaxias Movimiento propio: procedimientos de medición y estimación de errores. Velocidades espaciales: cómputo y limitaciones. Descripción de algunos modelos teóricos de dinámica de galaxias. Comparación entre observaciones y modelos teóricos. Efectos de la dinámica de galaxia en la formación y evolución estelar de las mismas. IV. Los cúmulos estelares Diferentes catalogaciones. Catálogos actualizados. Propiedades globales de los sistemas de cúmulos estelares. Distribuciones de edad, metalicidad, y dimensiones de los sistemas de cúmulos estelares. Destrucción de cúmulos estelares. Taza de Universidad Nacional de Córdoba FACULTAD DE MATEMÁTICA ASTRONOMÍA Y FÍSICA formación de cúmulos. Los cúmulos más viejos. Los cúmulos más jóvenes. Fenómeno de cúmulos estelares con formación estelar múltiple. V. Abundancias metálicas Determinaciones espectroscópicas y fotométricas. Calibraciones de indicadores de metalicidad. -

Age Distribution of Young Clusters and Field Stars in the Small Magellanic

A&A 452, 179–193 (2006) Astronomy DOI: 10.1051/0004-6361:20054559 & c ESO 2006 Astrophysics Age distribution of young clusters and field stars in the Small Magellanic Cloud, E. Chiosi1, A. Vallenari2,E.V.Held2, L. Rizzi3, and A. Moretti1 1 Astronomy Department, Padova University, Vicolo dell’Osservatorio 2, 35122 Padova, Italy e-mail: [email protected];[email protected] 2 INAF, Padova Observatory, Vicolo dell’Osservatorio 5, 35122 Padova, Italy e-mail: [antonella.vallenari;enrico.held]@oapd.inaf.it 3 Institute for Astronomy, 2680 Woodlawn Drive, Hawaii 96822-1897, USA Received 21 November 2005 / Accepted 15 February 2006 ABSTRACT Aims. In this paper we discuss the cluster and field star formation in the central part of the Small Magellanic Cloud. The main goal is to study the correlation between young objects and their interstellar environment. Methods. The ages of about 164 associations and 311 clusters younger than 1 Gyr are determined using isochrone fitting. The spatial distribution of the clusters is compared with the HI maps, with the HI velocity dispersion field, with the location of the CO clouds and with the distribution of young field stars. Results. The cluster age distribution supports the idea that clusters formed in the last 1 Gyr of the SMC history in a roughly continuous way with periods of enhancements. The two super-shells 37A and 304A detected in the HI distribution are clearly visible in the age distribution of the clusters: an enhancement in the cluster formation rate has taken place from the epoch of the shell formation. -

Overview of Trumpler Classification System

Tonight’s Novice topic is: An overview of the Trumpler classification system Compiled by b Ji m Wessel Johnson Space Center Astronomical Society Shapley’s Classification scheme a. Field Irregularities - filfeatures irregular star counts and associations. They differ from the normal distribution of stars, being more closely concentrated yet not enough to be studied. b. Star Associations - This category contains clusters that have distantly spaced stars sharing the same motion. e.g. Ursa Major group c. VLVery Loose an dIlCltd Irregular Clusters – These are very large and scattered clusters. e.g. Pleiades, Hyades, and the alpha Persei group. dLd. Loose Cl ust ers - very small amounts of stars and appear loose. Shapley gave M21 and M34 as examples of this type. e. Intermediate Rich & Concentrated – compact and concentrated. e.g. M38 f. Fairly Rich and Concentrated - This group is as compact as the ‘e’ group, yet with more stars; e .g . M37 g. Considerably Rich and Concentrated - This group is similarly compact as group ‘f’, yet contains more stars; the Jewel Box (NGC 4755) is in this class. Digital Sky Survey Hyades Berkeley 29 OC / Trumpler Classification system talk Robert Julius Trumpler • 1886-1956 • SiSwiss born, Amer ican AtAstronomer • Allegheny Obs -> Lick Obs. -> Berkeley • Independently discovered the absorption of light by interstellar dust (Boris Vorontsov- Velyaminov independently also found this). • Introduced term Galactic Clusters in 1925. • Elected to the National Academy of Sciences in 1932. • His classification system is the most commonly used means of identifying OCs today. • In 1930, he created a table of 37 Open Clusters that are no w kno w n as the Tru mpler Catalog . -

A Comparison of Optical and Near-Infrared Colours of Magellanic Cloud Star Clusters with Predictions of Simple Stellar Population Models

Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 385, 1535–1560 (2008) doi:10.1111/j.1365-2966.2008.12935.x A comparison of optical and near-infrared colours of Magellanic Cloud star clusters with predictions of simple stellar population models , P. M. Pessev,1 P. Goudfrooij,1 T. H. Puzia2 and R. Chandar3 4 1Space Telescope Science Institute, 3700 San Martin Drive, Baltimore, MD 21218, USA 2Herzberg Institute of Astrophysics, 5071 West Saanich Road, Victoria, BC V9E 2E7, Canada 3The Observatories of the Carnegie Institution of Washington, 813 Santa Barbara Street, Pasadena, CA 91101-1292, USA 4Department of Physics and Astronomy, The University of Toledo, 2801 West Bancroft Street, Toledo, OH 43606, USA Accepted 2008 January 8. Received 2008 January 6; in original form 2007 July 3 ABSTRACT We present integrated JHKS Two-Micron All-Sky Survey photometry and a compilation of integrated-light optical photoelectric measurements for 84 star clusters in the Magellanic Clouds. These clusters range in age from ≈200 Myr to >10 Gyr, and have [Fe/H] values from −2.2 to −0.1 dex. We find a spread in the intrinsic colours of clusters with similar ages and metallicities, at least some of which is due to stochastic fluctuations in the number of bright stars residing in low-mass clusters. We use 54 clusters with the most-reliable age and metallicity estimates as test particles to evaluate the performance of four widely used simple stellar population models in the optical/near-infrared (near-IR) colour–colour space. All mod- els reproduce the reddening-corrected colours of the old (10 Gyr) globular clusters quite well, but model performance varies at younger ages. -

INFRARED SURFACE BRIGHTNESS FLUCTUATIONS of MAGELLANIC STAR CLUSTERS1 Rosa A

The Astrophysical Journal, 611:270–293, 2004 August 10 A # 2004. The American Astronomical Society. All rights reserved. Printed in U.S.A. INFRARED SURFACE BRIGHTNESS FLUCTUATIONS OF MAGELLANIC STAR CLUSTERS1 Rosa A. Gonza´lez Centro de Radioastronomı´a y Astrofı´sica, Universidad Nacional Autonoma de Me´xico, Campus Morelia, Michoaca´n CP 58190, Mexico; [email protected] Michael C. Liu Institute for Astronomy, University of Hawaii, 2680 Woodlawn Drive, Honolulu, HI 96822; [email protected] and Gustavo Bruzual A. Centro de Investigaciones de Astronomı´a, Apartado Postal 264, Me´rida 5101-A, Venezuela; [email protected] Received 2003 November 27; accepted 2004 April 16 ABSTRACT We present surface brightness fluctuations (SBFs) in the near-IR for 191 Magellanic star clusters available in the Second Incremental and All Sky Data releases of the Two Micron All Sky Survey (2MASS) and compare them with SBFs of Fornax Cluster galaxies and with predictions from stellar population models as well. We also construct color-magnitude diagrams (CMDs) for these clusters using the 2MASS Point Source Catalog (PSC). Our goals are twofold. The first is to provide an empirical calibration of near-IR SBFs, given that existing stellar population synthesis models are particularly discrepant in the near-IR. Second, whereas most previous SBF studies have focused on old, metal-rich populations, this is the first application to a system with such a wide range of ages (106 to more than 1010 yr, i.e., 4 orders of magnitude), at the same time that the clusters have a very narrow range of metallicities (Z 0:0006 0:01, i.e., 1 order of magnitude only). -

Star Clusters Across Cosmic Time Arxiv:1812.01615V2 [Astro-Ph.GA

Star Clusters Across Cosmic Time Mark R. Krumholz1;2, Christopher F. McKee3, and Joss Bland-Hawthorn2;4;5 1Research School of Astronomy and Astrophysics, Australian National University, Canberra, ACT 2611, Australia; email: [email protected] 2Centre of Excellence for All Sky Astrophysics in Three Dimensions (ASTRO-3D), Australia 3Departments of Astronomy and of Physics, University of California, Berkeley, CA 94720, USA 4Sydney Institute for Astronomy, School of Physics A28, University of Sydney, NSW 2006, Australia 5Miller Professor, Miller Institute, University of California, Berkeley, CA 94720, USA arXiv:1812.01615v2 [astro-ph.GA] 13 Dec 2018 1 Xxxx. Xxx. Xxx. Xxx. 2019. 59:1{76 Keywords This article's doi: star clusters, star formation, globular clusters, open clusters and 10.1146/((please add article doi)) associations, stellar abundances Copyright c 2019 by Annual Reviews. All rights reserved Abstract Star clusters stand at the intersection of much of modern astrophysics: the interstellar medium, gravitational dynamics, stellar evolution, and cosmology. Here we review observations and theoretical models for the formation, evolution, and eventual disruption of star clusters. Current literature suggests a picture of this life cycle with several phases: • Clusters form in hierarchically-structured, accreting molecular clouds that convert gas into stars at a low rate per dynamical time until feedback disperses the gas. • The densest parts of the hierarchy resist gas removal long enough to reach high star formation efficiency, becoming dynamically- relaxed and well-mixed. These remain bound after gas removal. • In the first ∼ 100 Myr after gas removal, clusters disperse mod- erately fast, through a combination of mass loss and tidal shocks by dense molecular structures in the star-forming environment. -

STEP Survey – II. Structural Analysis of 170 Star Clusters in the SMC

MNRAS 507, 3312–3330 (2021) https://doi.org/10.1093/mnras/stab2297 Advance Access publication 2021 August 10 STEP survey – II. Structural analysis of 170 star clusters in the SMC M. Gatto ,1,2‹ V. Ripepi ,1 M. Bellazzini ,3 M. Tosi,3 M. Cignoni ,3,4,5 C. Tortora ,1 S. Leccia,1 G. Clementini,3 E. K. Grebel,6 G. Longo,2 M. Marconi 1 and I. Musella 1 1INAF – Osservatorio Astronomico di Capodimonte, Via Moiariello 16, I-80131 Naples, Italy 2Department of Physics, University of Naples Federico II, C.U. Monte Sant’Angelo, Via Cinthia, I-80126 Naples, Italy 3INAF – Osservatorio di Astrofisica e Scienza dello Spazio, Via Gobetti 93/3, I-40129 Bologna, Italy 4Physics Department, University of Pisa, Largo Bruno Pontecorvo 3, I-56127 Pisa, Italy 5INFN, Largo Bruno Pontecorvo 3, I-56127 Pisa, Italy 6Astronomisches Rechen-Institut, Zentrum fur¨ Astronomie der Universitat¨ Heidelberg, Monchhofstr¨ 12-14, D-69120 Heidelberg, Germany Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/mnras/article/507/3/3312/6347370 by guest on 27 September 2021 Accepted 2021 July 28. Received 2021 July 27; in original form 2021 May 13 ABSTRACT We derived surface brightness profiles in the g band for 170 Small Magellanic Cloud (SMC) star clusters (SCs) mainly located in the central region of the galaxy. We provide a set of homogeneous structural parameters obtained by fitting Elson–Fall–Freeman and King models. Through a careful analysis of their colour–magnitude diagrams we also supply the ages for a subsample of 134 SCs. For the first time, such a large sample of SCs in the SMC is homogeneously characterized in terms of their sizes, luminosities, and masses, widening the probed region of the parameter space, down to hundreds of solar masses. -

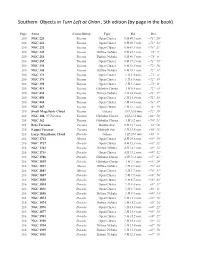

Southern Objects Paging

Southern Objects in Turn Left at Orion , 5th edition (by page in the book) Page Name Constellation Type RA Dec. 210 NGC 220 Tucana Open Cluster 0 H 40.5 min. −73° 24' 210 NGC 222 Tucana Open Cluster 0 H 40.7 min. −73° 23' 210 NGC 231 Tucana Open Cluster 0 H 41.1 min. −73° 21' 210 NGC 249 Tucana Diffuse Nebula 0 H 45.5 min. −73° 5' 210 NGC 261 Tucana Diffuse Nebula 0 H 46.5 min. −73° 6' 210 NGC 265 Tucana Open Cluster 0 H 47.2 min. −73° 29' 210 NGC 330 Tucana Open Cluster 0 H 56.3 min. −72° 28' 210 NGC 346 Tucana Diffuse Nebula 0 H 59.1 min. −72° 11' 210 NGC 371 Tucana Open Cluster 1 H 3.4 min. −72° 4' 210 NGC 376 Tucana Open Cluster 1 H 3.9 min. −72° 49' 210 NGC 395 Tucana Open Cluster 1 H 5.1 min. −72° 0' 210 NGC 419 Tucana Globular Cluster 1 H 8.3 min −72° 53' 210 NGC 456 Tucana Diffuse Nebula 1 H 14.4 min. −73° 17' 210 NGC 458 Tucana Open Cluster 1 H 14.9 min. −71° 33' 210 NGC 460 Tucana Open Cluster 1 H 14.6 min. −73° 17' 210 NGC 465 Tucana Open Cluster 1 H 15.7 min. −73° 19' 210 Small Magellanic Cloud Tucana Galaxy 0 H 53.0 min −72° 50' 212 NGC 104, 47 Tucanae Tucana Globular Cluster 0 H 24.1 min −62° 58' 214 NGC 362 Tucana Globular Cluster 1 H 3.2 min −70° 51' 215 Beta Tucanae Tucana Double Star 0 H 31.5 min. -

Hubble Captures Magellanic Gemstones in the Southern Sky 18 April 2006

Hubble Captures Magellanic Gemstones In The Southern Sky 18 April 2006 as is the case with densely packed crowds of hundreds of thousands of stars, called globular clusters. Or, they can be more loosely bound, irregularly shaped groupings of up to several thousands of stars, like the open clusters shown in this image. The stars in these open clusters are all relatively young and were born from the same cloud of interstellar gas. Just as old school-friends drift apart after graduation, the stars in an open cluster will only remain together for a limited time and Hubble has captured the most detailed images to date of gradually disperse into space, pulled away by the the open star clusters NGC 265 and NGC 290 in the gravitational tugs of other passing clusters and Small Magellanic Cloud - two sparkling sets of clouds of gas. Most open clusters dissolve within a gemstones in the southern sky. Two new composite few hundred million years, whereas the more tightly images taken with the Advanced Camera for Surveys bound globular clusters can exist for many billions onboard the NASA/ESA Hubble Space Telescope show of years. a myriad of stars in crystal clear detail. The brilliant open star clusters, NGC 265 and NGC 290, are located about Open star clusters make excellent astronomical 200,000 light-years away and are roughly 65 light-years across. Credit: European Space Agency & NASA laboratories. The stars may have different masses, but all are at about the same distance, move in the same general direction, and have approximately the same age and chemical composition.