Chapter 11: Flip Flops 6 (8)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Design and Evaluation of a Clock Multiplexing Circuit for the SSRL Booster Accelerator Timing System

SLAC-TN-15-018 Design and Evaluation of a Clock Multiplexing Circuit for the SSRL Booster Accelerator Timing System Million Araya† August 21, 2015 Seattle Central Community College, Seattle, WA CCI Program, SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory SPEAR3 is a 234 m circular storage ring at SLAC’s synchrotron radiation facility (SSRL) in which a 3 GeV electron beam is stored for user access. Typically the electron beam decays with a time constant of approximately 10hr due to electron lose. In order to replenish the lost electrons, a booster synchrotron is used to accelerate fresh electrons up to 3GeV for injection into SPEAR3. In order to maintain a constant electron beam current of 500mA, the injection process occurs at 5 minute intervals. At these times the booster synchrotron accelerates electrons for injection at a 10Hz rate. A 10Hz 'injection ready' clock pulse train is generated when the booster synchrotron is operating. Between injection intervals-where the booster is not running and hence the 10 Hz ‘injection ready’ signal is not present-a 10Hz clock is derived from the power line supplied by Pacific Gas and Electric (PG&E) to keep track of the injection timing. For this project I constructed a multiplexing circuit to 'switch' between the booster synchrotron 'injection ready' clock signal and PG&E based clock signal. The circuit uses digital IC components and is capable of making glitch-free transitions between the two clocks. This report details construction of a prototype multiplexing circuit including test results and suggests improvement opportunities for the final design. I. Introduction The ultimate purpose of a synchrotron radiation facility is to generate stable, high-power beams of light spanning from the Infrared to x-ray portion of the electromagnetic spectrum. -

V850 Standby Modes

Application Note V850 Standby Modes V850ES/SG2 V850ES/SJ2 Document No. U18825EE1V0AN00 Date Published June 2007 © NEC Electronics Corporation June 2007 Printed in Germany NOTES FOR CMOS DEVICES 1 VOLTAGE APPLICATION WAVEFORM AT INPUT PIN Waveform distortion due to input noise or a reflected wave may cause malfunction. If the input of the CMOS device stays in the area between VIL (MAX) and VIH (MIN) due to noise, etc., the device may malfunction. Take care to prevent chattering noise from entering the device when the input level is fixed, and also in the transition period when the input level passes through the area between VIL (MAX) and VIH (MIN). 2 HANDLING OF UNUSED INPUT PINS Unconnected CMOS device inputs can be cause of malfunction. If an input pin is unconnected, it is possible that an internal input level may be generated due to noise, etc., causing malfunction. CMOS devices behave differently than Bipolar or NMOS devices. Input levels of CMOS devices must be fixed high or low by using pull-up or pull-down circuitry. Each unused pin should be connected to VDD or GND via a resistor if there is a possibility that it will be an output pin. All handling related to unused pins must be judged separately for each device and according to related specifications governing the device. 3 PRECAUTION AGAINST ESD A strong electric field, when exposed to a MOS device, can cause destruction of the gate oxide and ultimately degrade the device operation. Steps must be taken to stop generation of static electricity as much as possible, and quickly dissipate it when it has occurred. -

Generate a Clock Signal from a Crystal Oscillator

www.ti.com Product Overview Generate a Clock Signal from a Crystal Oscillator Clocked Device U CLK Figure 1-1. Using an Unbuffered Inverter and Schmitt-Trigger Inverter to Generate a Clock Signal From a Crystal Oscillator Design Considerations • Drive crystal oscillators directly • Can be disabled with added logic • Allows for selectable system clocks with multiple crystals • Outputs a clean and reliable square wave • See the Use of the CMOS Unbuffered Inverter in Oscillator Circuits Application Report for more information about this use case. • Need additional assistance? Ask our engineers a question on the TI E2E™ logic support forum Recommended Parts Part Number Automotive Qualified VCC Range Features SN74LVC2GU04-Q1 ✓ 1.65 V — 5.5 V Dual unbuffered inverter SN74LVC2GU04 SN74AHC1GU04 2 V — 5.5 V Single unbuffered inverter SN74AUC1GU04 0.8 V — 2.7 V Single unbuffered inverter SN74LVC1G17-Q1 ✓ 1.65 V — 5.5 V Single Schmitt-trigger buffer SN74LVC1G17 For more devices, browse through the online parametric tool where you can sort by desired voltage, channel numbers, and other features. SCEA099 – OCTOBER 2020 Generate a Clock Signal from a Crystal Oscillator 1 Submit Document Feedback Copyright © 2020 Texas Instruments Incorporated IMPORTANT NOTICE AND DISCLAIMER TI PROVIDES TECHNICAL AND RELIABILITY DATA (INCLUDING DATASHEETS), DESIGN RESOURCES (INCLUDING REFERENCE DESIGNS), APPLICATION OR OTHER DESIGN ADVICE, WEB TOOLS, SAFETY INFORMATION, AND OTHER RESOURCES “AS IS” AND WITH ALL FAULTS, AND DISCLAIMS ALL WARRANTIES, EXPRESS AND IMPLIED, INCLUDING WITHOUT LIMITATION ANY IMPLIED WARRANTIES OF MERCHANTABILITY, FITNESS FOR A PARTICULAR PURPOSE OR NON-INFRINGEMENT OF THIRD PARTY INTELLECTUAL PROPERTY RIGHTS. These resources are intended for skilled developers designing with TI products. -

VLSI Digital Signal Processing

CLOCKS Clocks in Digital Systems • Why are clocks and clocked memory registers needed inside digital systems? • Clocks pace the flow of data inside digital processors • The exact speed of data through circuits is impossible to predict accurately due to factors such as: – Fabrication process variations – Supply voltage variations “PVT variations” – Temperature variations – Countless parasitic effects (e.g., wire-to-wire capacitances) – Data-dependent variations (e.g., calculating 1 OR 1 = 1 requires a different delay than 1 OR 0 = 1) © B. Baas 322 Clocks in Digital Systems • Clocked memory elements slow down the fastest signals, wait until all signals have finished propagating through the combinational logic in the stage*, and then release them into the next stage simultaneously, controlled by the active edge of the clock signal • * This is why we care about clock only the single slowest signal in a block (max propagation delay) when finding the maximum clock frequency © B. Baas 323 Clocks in Digital Systems • All paths within a digital system consist of an input register, (optionally) followed by combinational logic, followed by an output register • Therefore: – If we can make this structure work under all conditions, we can build a robust digital system – We should analyze this structure carefully clock a combinational out b logic c_p1 c_p3 © B. Baas c_p2 324 Robust Clock Design • Edge-triggered memory elements (flip-flops) are generally more robust than level-sensitive memory elements (transparent latches) • Always follow these rules in this class, and for the most robust designs: 1. Only clock signals may connect to flip-flop or latch clock inputs • A simpler circuit may sometimes be possible if a logic signal is connected to a clock input, but do not do it for robustness • always @(posedge key) begin 2. -

Tms320f280x, Tms320c280x, Tms320f2801x Digital Signal Processors

TMS320F2809, TMS320F2808, TMS320F2806, TMS320F2802, TMS320F2801, TMS320C2802, TMS320F2809, TMS320F2808, TMS320F2806,TMS320C2801, TMS320F2802, TMS320F28016, TMS320F2801, TMS320F28015TMS320C2802, www.ti.com TMS320C2801,SPRS230P – OCTOBER TMS320F28016, 2003 – REVISED TMS320F28015 FEBRUARY 2021 SPRS230P – OCTOBER 2003 – REVISED FEBRUARY 2021 TMS320F280x, TMS320C280x, TMS320F2801x digital signal processors 1 Features • Three 32-bit CPU timers • Enhanced control peripherals • High-performance static CMOS technology – Up to 16 PWM outputs – 100 MHz (10-ns cycle time) – Up to 6 HRPWM outputs with 150-ps MEP – 60 MHz (16.67-ns cycle time) resolution – Low-power (1.8-V core, 3.3-V I/O) design – Up to four capture inputs • JTAG boundary scan support – Up to two quadrature encoder interfaces – IEEE Standard 1149.1-1990 Standard Test – Up to six 32-bit/six 16-bit timers Access Port and Boundary Scan Architecture • Serial port peripherals • High-performance 32-bit CPU (TMS320C28x) – Up to 4 SPI modules – 16 × 16 and 32 × 32 MAC operations – Up to 2 SCI (UART) modules – 16 × 16 dual MAC – Up to 2 CAN modules – Harvard bus architecture – One Inter-Integrated-Circuit (I2C) bus – Atomic operations • 12-bit ADC, 16 channels – Fast interrupt response and processing – 2 × 8 channel input multiplexer – Unified memory programming model – Two sample-and-hold – Code-efficient (in C/C++ and Assembly) – Single/simultaneous conversions • On-chip memory – Fast conversion rate: – F2809: 128K × 16 flash, 18K × 16 SARAM 80 ns - 12.5 MSPS (F2809 only) F2808: 64K × 16 -

Phase Alignment of Asynchronous External

PHASEALIGNMENTOFASYNCHRONOUSEXTERNALCLOCK CONTROLLABLEDEVICESTOPERIODICMASTERCONTROLSIGNALUSING THEPERIODICEVENTSYNCHRONIZATIONUNIT by CharlesNicholasOstrander Athesissubmittedinpartialfulfillment oftherequirementsforthedegree of MasterofScience in ElectricalEngineering MONTANASTATEUNIVERSITY Bozeman,Montana May2009 ©COPYRIGHT by CharlesNicholasOstrander 2009 AllRightsReserved ii APPROVAL ofathesissubmittedby CharlesNicholasOstrander Thisthesishasbeenreadbyeachmemberofthethesiscommitteeandhasbeen foundtobesatisfactoryregardingcontent,Englishusage,format,citation,bibliographic style,andconsistency,andisreadyforsubmissiontotheDivisionofGraduateEducation. Dr.BrockJ.LaMeres ApprovedfortheDepartmentElectricalEngineering Dr.RobertC.Maher ApprovedfortheDivisionofGraduateEducation Dr.CarlA.Fox iii STATEMENTOFPERMISSIONTOUSE Inpresentingthisthesisinpartialfulfillmentoftherequirementsfora master’sdegreeatMontanaStateUniversity,IagreethattheLibraryshallmakeit availabletoborrowersunderrulesoftheLibrary. IfIhaveindicatedmyintentiontocopyrightthisthesisbyincludinga copyrightnoticepage,copyingisallowableonlyforscholarlypurposes,consistentwith “fairuse”asprescribedintheU.S.CopyrightLaw.Requestsforpermissionforextended quotationfromorreproductionofthisthesisinwholeorinpartsmaybegranted onlybythecopyrightholder. CharlesNicholasOstrander May2009 iv TABLEOFCONTENTS 1.INTRODUCTION .......................................................................................................... 1 -

7. Latches and Flip-Flops

Chapter 7 – Latches and Flip-Flops Page 1 of 18 7. Latches and Flip-Flops Latches and flip-flops are the basic elements for storing information. One latch or flip-flop can store one bit of information. The main difference between latches and flip-flops is that for latches, their outputs are constantly affected by their inputs as long as the enable signal is asserted. In other words, when they are enabled, their content changes immediately when their inputs change. Flip-flops, on the other hand, have their content change only either at the rising or falling edge of the enable signal. This enable signal is usually the controlling clock signal. After the rising or falling edge of the clock, the flip-flop content remains constant even if the input changes. There are basically four main types of latches and flip-flops: SR, D, JK, and T. The major differences in these flip-flop types are the number of inputs they have and how they change state. For each type, there are also different variations that enhance their operations. In this chapter, we will look at the operations of the various latches and flip- flops. 7.1 Bistable Element The simplest sequential circuit or storage element is a bistable element, which is constructed with two inverters connected sequentially in a loop as shown in Figure 1. It has no inputs and two outputs labeled Q and Q’. Since the circuit has no inputs, we cannot change the values of Q and Q’. However, Q will take on whatever value it happens to be when the circuit is first powered up. -

Introduction (Pdf)

chapter1.fm Page 1 Thursday, August 17, 2000 4:43 PM CHAPTER 1 INTRODUCTION The evolution of digital circuit design n Compelling issues in digital circuit design n How to measure the quality of digital design n Valuable references 1.1 A Historical Perspective 1.2 Issues in Digital Integrated Circuit Design 1.3 Quality Metrics of A Digital Design 1.4 Summary 1.5 To Probe Further 1 chapter1.fm Page 2 Thursday, August 17, 2000 4:43 PM 2 INTRODUCTION Chapter 1 1.1A Historical Perspective The concept of digital data manipulation has made a dramatic impact on our society. One has long grown accustomed to the idea of digital computers. Evolving steadily from main- frame and minicomputers, personal and laptop computers have proliferated into daily life. More significant, however, is a continuous trend towards digital solutions in all other areas of electronics. Instrumentation was one of the first noncomputing domains where the potential benefits of digital data manipulation over analog processing were recognized. Other areas such as control were soon to follow. Only recently have we witnessed the con- version of telecommunications and consumer electronics towards the digital format. Increasingly, telephone data is transmitted and processed digitally over both wired and wireless networks. The compact disk has revolutionized the audio world, and digital video is following in its footsteps. The idea of implementing computational engines using an encoded data format is by no means an idea of our times. In the early nineteenth century, Babbage envisioned large- scale mechanical computing devices, called Difference Engines [Swade93]. Although these engines use the decimal number system rather than the binary representation now common in modern electronics, the underlying concepts are very similar. -

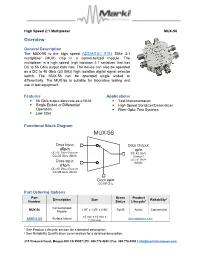

MUX-56 Overview

High Speed 2:1 Multiplexer MUX-56 Overview General Description The MUX-56 is the high speed ADSANTEC 5153 SiGe 2:1 multiplexer (MUX) chip in a connectorized module. The multiplexer is a high speed, high isolation 2:1 serializer that has DC to 56 Gb/s output data rate. The device can also be operated as a DC to 40 Gb/s (20 GHz) high isolation digital signal selector switch. The MUX-56 can be operated single ended or differentially. The MUX-56 is suitable for laboratory testing and use in test equipment. Features Applications ▪ 56 Gb/s output data rate as a MUX ▪ Test Instrumentation ▪ Single Ended or Differential ▪ High Speed Serializer/Deserializer Operation ▪ Fiber Optic Test Systems ▪ Low Jitter Functional Block Diagram MUX-56 Data Input Data Output d0p/n qp/n DC-40 Gb/s (Switch) DC-40 Gb/s DC-28 Gb/s (MUX) (Switch) Data input DC-56 Gb/s (MUX) d1p/n DC-40 Gb/s (Switch) DC-28 Gb/s (MUX) Clock cp/n DC-28 GHz Part Ordering Options Part Green Product Description Size Reliability2 Number Status Lifecycle1 Connectorized MUX-56 1.05” x 1.05” x 0.56” RoHS Active Commercial Module 10 mm x 10 mm x ASNT-5153 Surface Mount See adsantec.com 1.205 mm 1 See Product Lifecycle section for a detailed description. 2 See Reliability Qualification Level section for a detailed description. 215 Vineyard Court, Morgan Hill CA 95037 | Ph: 408.778.4200 | Fax: 408.778.4300 | [email protected] High Speed 2:1 Multiplexer MUX-56 Application Information Overview The MUX-56 is a high speed multiplexer module designed for use in a laboratory or test equipment environment. -

ECE380 Digital Logic Flip-Flops

ECE380 Digital Logic Flip-Flops, Registers and Counters: Flip-Flops Electrical & Computer Engineering Dr. D. J. Jackson Lecture 25-1 Flip-flops • The gated latch circuits presented are level sensitive and can change states more than once during the ‘active’ period of the clock signal • Circuits (storage elements) that can change their state no more than once during a clock period are also useful • Two types of circuits with such behavior – Master-slave flip-flip – Edge-triggered flip-flop Electrical & Computer Engineering Dr. D. J. Jackson Lecture 25-2 1 Master-slave D flip-flop • Consists of 2 gated D latches –The first, master, changes its state while clock=1 – The second, slave, changes its state while clock=0 Master Slave Q Q m s D D Q D Q Q Clk Q Clk Q Clock Q 38 transistors Electrical & Computer Engineering Dr. D. J. Jackson Lecture 25-3 Master-slave D flip-flop • When clock=1, the master tracks the values of the D input signal and the slave does not change – Thus Qm follows any changes in D and Qs remains constant • When the clock signal changes to 0, the master stage stops following the changes in the D input signal • At the same time, the slave stage responds to the value of Qm and changes states accordingly •Since Qm does not change when clock=0, the slave stage undergoes at most one change of state during a clock cycle • From an output point of view, the circuit changes Qs (its output) at the negative edge of the clock signal Electrical & Computer Engineering Dr. -

Digital Timing: Clock Signals, Jitter, Hystereisis, and Eye Diagrams

Digital Timing: Clock Signals, Jitter, Hystereisis, and Eye Diagrams Overview Learn about digital timing of clock signals and common terminology such as jitter, drift, rise and fall time, settling time, hysteresis, and eye diagrams. This tutorial is part of the Instrument Fundamentals series. Contents wwClock Signals wwCommon Terminology a. Jitter b. Drift c. Rise Time, Fall Time, and Aberrations d. Settlling Time e. Hysteresis f. Skew g. Eye Diagram wwSummary ni.com/instrument-fundamentals Next Digital Timing: Clock Signals, Jitter, Hystereisis, and Eye Diagrams Clock Signals When sending digital signals, a 0 or 1 is being sent. However, for different devices to communicate, timing information needs to be associated with the bits sent. Digital waveforms are referenced to clock signals. You can think of a clock signal as a conductor that provides timing signals to all parts of a digital system so that each process may be triggered at a precise moment. A clock signal is a square wave with a fixed period. The period is measured from the edge of one clock to the next similar edge of the clock; most often is it measured from one rising edge to the next. The frequency of the clock can be calculated by the inverse of the clock period. Figure 1. Digital waveforms are referenced to clock signals, which have a fixed period to synchronize digital transmitters and receivers during data transfer. The duty cycle of a clock signal is the percentage of the waveform period that the waveform is at a logic high level. Figure 2 shows the difference between two waveforms with different duty cycles. -

"Clock Distribution in Synchronous Systems"

474 CLOCK DISTRIBUTION IN SYNCHRONOUS SYSTEMS CLOCK DISTRIBUTION IN SYNCHRONOUS SYSTEMS In a synchronous digital system, the clock signal is used to define a time reference for the movement of data within that system. Because this function is vital to the operation of a synchronous system, much attention has been given to the characteristics of these clock signals and the networks used in their distribution. Clock signals are often regarded as simple control signals; however, these signals have some very special characteristics and attributes. Clock signals are typically loaded with the greatest fanout, travel over the greatest dis- tances, and operate at the highest speeds of any signal, either control or data, within the entire system. Because the data signals are provided with a temporal reference by the clock signals, the clock waveforms must be particularly clean and sharp. Furthermore, these clock signals are particularly af- fected by technology scaling, in that long global interconnect lines become much more highly resistive as line dimensions are decreased. This increased line resistance is one of the pri- mary reasons for the increasing significance of clock distribu- tion on synchronous performance. Finally, the control of any differences in the delay of the clock signals can severely limit the maximum performance of the entire system and create catastrophic race conditions in which an incorrect data signal may latch within a register. Most synchronous digital systems consist of cascaded banks of sequential registers with combinatorial logic be- tween each set of registers. The functional requirements of the digital system are satisfied by the logic stages.