The Life and Work of Alexander Knox ( 1757

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Golden Cord

THE GOLDEN CORD A SHORT BOOK ON THE SECULAR AND THE SACRED ' " ' ..I ~·/ I _,., ' '4 ~ 'V . \ . " ': ,., .:._ C HARLE S TALIAFERR O THE GOLDEN CORD THE GOLDEN CORD A SHORT BOOK ON THE SECULAR AND THE SACRED CHARLES TALIAFERRO University of Notre Dame Press Notre Dame, Indiana Copyright © 2012 by the University of Notre Dame Press Notre Dame, Indiana 46556 www.undpress.nd.edu All Rights Reserved Manufactured in the United States of America Library of Congress Cataloging- in- Publication Data Taliaferro, Charles. The golden cord : a short book on the secular and the sacred / Charles Taliaferro. pages cm Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN-13: 978-0-268-04238-7 (pbk. : alk. paper) ISBN-10: 0-268-04238-1 (pbk. : alk. paper) 1. God (Christianity) 2. Life—Religious aspects—Christianity. 3. Self—Religious aspects—Christianity. 4. Redemption—Christianity. 5. Cambridge Platonism. I. Title. BT103.T35 2012 230—dc23 2012037000 ∞ The paper in this book meets the guidelines for permanence and durability of the Committee on Production Guidelines for Book Longevity of the Council on Library Resources. CONTENTS Acknowledgments vii Introduction 1 CHAPTER 1 Love in the Physical World 15 CHAPTER 2 Selves and Bodies 41 CHAPTER 3 Some Big Pictures 61 CHAPTER 4 Some Real Appearances 81 CHAPTER 5 Is God Mad, Bad, and Dangerous to Know? 107 CHAPTER 6 Redemption and Time 131 CHAPTER 7 Eternity in Time 145 CHAPTER 8 Glory and the Hallowing of Domestic Virtue 163 Notes 179 Index 197 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I am deeply grateful for the patience, graciousness, support, and encour- agement of the University of Notre Dame Press’s senior editor, Charles Van Hof. -

Defining Man As Animal Religiosum in English Religious Writing C. 1650–C

Accepted for publication in Church History for publication in September 2019. Title: Defining Man as Animal Religiosum in English Religious Writing c. 1650–c. 1700 Abstract: This article surveys the emergence and usage of the redefinition of man not as animal rationale (a rational animal) but as animal religiosum (a religious animal) by numerous English theologians between 1650 and 1700. Across the continuum of English protestant thought human nature was being re-described as unique due to its religious, not primarily its rational, capabilities. The article charts this appearance as a contribution to debates over man’s relationship with God; then its subsequent incorporation into the subsequent debate over the theological consequences of arguments in favor of animal rationality, as well as its uses in anti-atheist apologetics; and then the sudden disappearance of the definition of man as animal religiosum at the beginning of the eighteenth century. In doing so, the article hopes to make a useful contribution to our understanding of changing early modern understandings of human nature by reasserting the significance of theological debates within the context of seventeenth-century debate about the relationship between humans and beasts and by offering a more wide-ranging account of man as animal religiosum than the current focus on ‘Cambridge Platonism’ and ‘Latitudinarianism’ allows. Keywords: Animal rationality, reason, 17th c. England, Cambridge Platonism, Latitudinarianism. Contact Details: Dr R J W Mills Dept. of History, University College London Gower Street London WC1E 6BT United Kingdom [email protected] 1 Accepted for publication in Church History for publication in September 2019. -

The Arms of the Scottish Bishoprics

UC-NRLF B 2 7=13 fi57 BERKELEY LIBRARY UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORN'A \o Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2008 with funding from IVIicrosoft Corporation http://www.archive.org/details/armsofscottishbiOOIyonrich /be R K E L E Y LIBRARY UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORN'A h THE ARMS OF THE SCOTTISH BISHOPRICS. THE ARMS OF THE SCOTTISH BISHOPRICS BY Rev. W. T. LYON. M.A.. F.S.A. (Scot] WITH A FOREWORD BY The Most Revd. W. J. F. ROBBERDS, D.D.. Bishop of Brechin, and Primus of the Episcopal Church in Scotland. ILLUSTRATED BY A. C. CROLL MURRAY. Selkirk : The Scottish Chronicle" Offices. 1917. Co — V. PREFACE. The following chapters appeared in the pages of " The Scottish Chronicle " in 1915 and 1916, and it is owing to the courtesy of the Proprietor and Editor that they are now republished in book form. Their original publication in the pages of a Church newspaper will explain something of the lines on which the book is fashioned. The articles were written to explain and to describe the origin and de\elopment of the Armorial Bearings of the ancient Dioceses of Scotland. These Coats of arms are, and have been more or less con- tinuously, used by the Scottish Episcopal Church since they came into use in the middle of the 17th century, though whether the disestablished Church has a right to their use or not is a vexed question. Fox-Davies holds that the Church of Ireland and the Episcopal Chuich in Scotland lost their diocesan Coats of Arms on disestablishment, and that the Welsh Church will suffer the same loss when the Disestablishment Act comes into operation ( Public Arms). -

A Cloud of Witnesses

^^fyvVrrv^ "** " i n <n » HW i +uMm*m»****WBKmafi9m<«lF»<"< «* LIBRARY OF CONGRESS, A Cloud of Witnesses CONTAINING Selections from the Writings of Poets and Other Literary and Celebrated Persons, Expressive of the Universal Triumph of Good THB LIBRARY Over Evil. OF CONGRESS / WASHINGTON, • By J. W. Hanson, A, M., D. D. One far-off divine event, To which the whole creation moves. Tennyson. Out of the Strong came forth Sweetness. Bible. /7> M CHICAGO: The Star and Covenant Office. 1880. 9h /4 COPYRIGHT, d. W. HANSON, 1880, GEO, DANIELS, PRINTER. CHICAGO. Preface, Poets and philosophers, writers and thinkers, those who have weighed the problem of human destiny, whatever may have been their educational bias, or religious proclivities, have often risen to a more or less distinct conception of the thought that evil is transient and good eternal, and that the Author of man will ultimately perfect his chief work. The deliverance of the whole human family from sin and sorrow, its final holiness and happiness, has been the thought of multitudes, even when the prevailing doctrines around them were wholly hostile; and, in and out of Christendom, the great thought has scarcely ever been without witnesses among men. It was dis- tinctly revealed by Jesus, in his Gospel, and forms the burthen of prophet and apostle, bard and seer, from Genesis to Revelation, and it has also brightened the pages of literature in every age of the world, since man possessed a literature. Twenty-five years ago the compiler of this volume published a little work entitled "Witnesses to the Truth, containing Passages from Distinguished Authors, developing the great Truth of Uni- versal Salvation." The subsequent quarter- century has added im- mensely to the testimony that men of genius have given in attesta- tion to the sublimest fact in human history that has ever come to human knowledge, and the further reading of the compiler has en- abled him to adduce authors whose words were then unknown to him, some of whom are among the best who have ever written. -

Paisley Commercial School

RLHF Journal Vol.5 (1993) 5. Troubled Times John MaIden The period between 1520 and 1620 was one of radical change on the religious front when not only did the method of worship alter, but also the administration of the local economy moved into secular control. By 1520 the Monastery and Abbey of Paisley were under the control of Abbot Robert Shaw who was elected Bishop of Moray in 1525. Shaw was the nephew of the previous Abbot, the builder George Shaw, and saw the position of Abbot and the worship in the Church at its height of power, ceremony and colour. It is often forgotten that the churches were full of colour, as today we are used to the austere plain stonework and lack of ornament. An example of the richness of the fittings in the Abbey at this period is given by the printed, and coloured, Missal presented by one of the Monks, Robert Kerr, to the altar of the Virgin in the early 1550's. The high quality of the text, printed in Paris, and the jewel-like appearance of the illustrations gives a hint of the grandeur on public view. Now in the care of the National Library of Scotland, this Missal is the only known service book to survive from the Monastery. Shaw was succeeded, as the last religious Abbot, by John Hamilton, a young monk from Kilwinning, who was the illegitimate son of the Earl of Arran. Hamilton became one of the outstanding figures during the time of crisis which led to the dissolution of monasteries in Scotland. -

Hazlett-Campbell-Est

Series Description St. Louis Circuit Court Records Hazlett Kyle Campbell Case St. Louis Union Trust Company, et al. v Clarke, Charles H., et al – 23694-C Abstract: The Hazlett Kyle Campbell Case consists of 17 cubic feet of court papers, transcripts, and exhibits ranging in date from 1938 through 1944. The documents in this collection offer a wealth of information on social, cultural, and economic history as it relates to one of St. Louis’s preeminent nineteenth-century families. Provenance: Office of the Circuit Clerk, City of St. Louis. This case originated with the death of Hazlett Kyle Campbell in March 1938. He left behind an estate valued at approximately $1,850,000. More than 1,000 people eventually came forward claiming to be heirs of this estate. The documents included in this finding aid were filed in the St. Louis Circuit Court between 1938 and 1944. Missouri State Archives staff processed and prepared the materials for microfilm in 2006-2007. Series Title: St. Louis Union Trust Company, et al. v Clarke, Charles H., et al - 23694-C Series Inclusive Dates: 1938-1944 Volume: 17 cubic feet (16 cubic feet of legal size file folders and 3 oversized boxes) Physical Description: The series consists of court papers, transcripts and exhibits (photographs, birth and death records, lineage charts, diaries, wills, bibles, etc.). The majority of these documents are original, however, there exists a considerable number of photostat copies as well. All documents have been flattened and cleaned of dirt and dust that accumulated through the years. Items used to attach documents, such as grommets, straight pins, ribbons, paper clips, and staples have been removed to allow for filming and scanning. -

Lviemoirs of JOHN KNOX

GENEALOGICAL lVIEMOIRS OF JOHN KNOX AXIJ OF THE FAMILY OF KNOX BY THE REV. CHARLES ROGERS, LL.D. fF'.LLOW OF THE ROYAL HISTORICAL SOCIETY, FELLOW OF THE SOCIETY OF ANTIQUARIES OF SCOTLAXD, FELLOW OF THE ROYAL SOCIETY OF XORTHER-N A:NTIQ:;ARIES, COPENHAGEN; FELLOW OF THE ROYAL SOCIETY OF NEW SOCTH WALES, ASSOCIATE OF THE IMPRRIAL ARCIIAWLOGICAL SOCIETY OF Rl'SSIA, MEMBER OF THE HISTORICAL SOCIETY OF QL'EBEC, MEMBER OF THE HISTORICAL SOCIETY OF PENNSYLVANIA, A!'i'D CORRESPOXDING MEMBER OF THE HISTORICAL AND GENEALOGICAL SOCIETY OF NEW ENGLA:ND PREF ACE. ALL who love liberty and value Protestantism venerate the character of John Knox; no British Reformer is more entitled to the designation of illustrious. By three centuries he anticipated that parochial system of education which has lately become the law of England; by nearly half that period he set forth those principles of civil and religious liberty which culminated in a system of constitutional government. To him Englishmen are indebted for the Protestant character of their "Book of Common Prayer;" Scotsmen for a Reforma tion so thorough as permanently to resist the encroachments of an ever aggressive sacerdotalism. Knox belonged to a House ancient and respectable; but those bearing his name derive their chiefest lustre from 1eing connected with a race of which he was a member. The family annals presented in these pages reveal not a few of the members exhibiting vast intellectual capacity and moral worth. \Vhat follows is the result of wide research and a very extensive correspondence. So many have helped that a catalogue of them ,...-ould be cumbrous. -

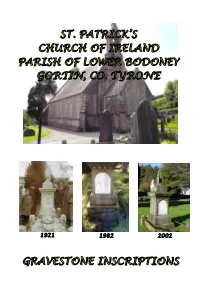

St. Patrick's C of I, Gortin

1921 1982 2002 ST. PATRICK’S PARISH CHURCH, LOWER BADONEY, GORTIN Thanks to Hazel Robinson for patiently helping to decipher and make the gravestone recordings on our many journeys to this peaceful graveyard of our ancestors. Colour photographs by Ann Robinson. Black & White photograph courtesy of Ann Dark. © 2017 A.K. ROBINSON 2 ST. PATRICK’S PARISH CHURCH, LOWER BADONEY, GORTIN ST. PATRICK’S CHURCH OF IRELAND, PARISH OF LOWER BODONEY (BADONEY), GORTIN, CO. TYRONE. The Parish of Badoney was originally a very large parish, stretching up the Glenelly Valley, with the oldest church site in the townland of Glenroan. This church is also called St. Patrick and this part of the parish eventually became Upper Badoney. The parish of Badoney was separated into two parts in 1730 and the first church of Lower Badoney, St. Patrick’s, was built in the village of Gortin. It was not until 1774 that the parish of Lower Badoney was constituted. The two parts were reunited again in 1924. In 1856 a new church was built in Lower Badoney at a cost of £1,921-15-00. This is the current church and is on a slightly different site to the older one. For many years parts of the old church, and the school, could be seen in the graveyard. In 1939 the graveyard was measured by J.C.M. Knox, Londonderry. In the 1980s all signs of the old church were removed when the graveyard was “tidied up.” From the First edition of the Ordnance Survey Maps (1832-1846) the position of the first church can be seen, along with the school. -

'Borgs', Boats and the Beginnings of Islay's Medieval Parish Network?

‘Borgs’, Boats and the Beginnings of Islay’s Medieval Parish Network? Alan Macniven Introduction THE Viking1 expansion of c. AD 800 to 1050 is often assigned a formative role in the cultural and political trajectories of Europe and the North Atlantic. The Viking conquest of Anglo-Saxon England, for example, is well known, with its ‘Great Heathen Armies’, metric tonnes of silver ‘Danegeld’, and plethora of settlement names in -býr/-bœr, -þorp, and -þveitr.2 One aspect of this diaspora which remains relatively obscure, however, is its impact on the groups of islands and skerries off Scotland’s west coast which together comprise the Inner Hebrides. This paper will focus on one of these, the isle of Islay, at the south-west extremity of the archipelago, and about half-way between the mainlands of Scotland and Ireland (Figure 1). In so doing, it will question the surprisingly resilient assumption that the Inner Hebridean Viking Age was characterised largely by cultural stability and continuity from the preceding period rather than population displacement, cultural disjuncture or the lasting introduction of new forms of societal organisation. For Norwegian Vikings, it seems likely to have been the lure of Irish riches that kick-started the movement west. The economic opportunities provided by Ireland’s battlefields and marketplaces, in terms of silver, slaves, or simply the chance to build a reputation as a war-leader, offered a gateway to social status of a type fast disappearing in the Scandinavian homelands.3 It is reasonable to assume that most Norse warbands arriving in the Irish Sea 1 The term ‘Viking’ is an emotive one, fraught with pejorative connotations (eg. -

Mysticism and Conversion in Seventeenth-Century England By

Transfiguring the Ineffable: Mysticism and Conversion in Seventeenth-Century England By Chance Woods Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Vanderbilt University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in English August 11, 2017 Nashville, Tennessee Approved: Leah Marcus, Ph.D. Kathryn Schwarz, Ph.D. Scott Juengel, Ph.D. William Franke, Ph.D. Paul Lim, Ph.D. Copyright © 2017 by Chance Woods All Rights Reserved ii DEDICATION This dissertation is dedicated to the memory of my father, Perry Woods (1939-2006), to the memory of my mother, Frances Woods (1950-2016), and to Susanne. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to express my gratitude to the many friends, teachers, and colleagues who have contributed to the completion of this dissertation project and to my overall graduate education. Before and after coming to Vanderbilt University for doctoral studies, my mentors at the University of Oklahoma (my alma mater) provided endless support and encouragement. A special note of thanks goes to them: Luis Cortest, David K. Anderson, and Kyle Harper. I hope to emulate the standards of academic excellence these friends embody. Vanderbilt University has proven to be an ideal institution for graduate work. A Ph.D. student could not ask for a better support network. Over the years, I have learned a great deal from faculty in the Departments of History and Philosophy. In particular, I would like to thank Professor Peter Lake for unique seminars in early modern history as well as Professor Lenn Goodman for brilliant seminars on Plato and Spinoza. -

Elizabeth Singer Rowe

Elizabeth Singer Rowe: Dissent, Influence, and Writing Religion, 1690-1740 Jessica Haldeman Clement PhD University of York English and Related Literature September 2017 Abstract This thesis addresses the religious poetry of Elizabeth Singer Rowe, arguing that her Dissenting identity provides an important foundation on which to which to critically consider her works. Although Rowe enjoyed a successful career, with the majority of her writing seeing multiple editions throughout her lifetime and following her death, her posthumous reputation persists as an overly pious and reclusive religious poet. Moving past these stereotypes, my thesis explores Rowe’s engagement with poetry as a means to convey various aspects of Dissent and her wider religious community. This thesis also contributes to the wider understanding of Dissenting creative writing and influence in the years following the Glorious Revolution of 1688, using Rowe’s work as a platform to demonstrate complexities and cultural shifts within the work of her contemporaries. My argument challenges the notion that Rowe’s religious poetry was a mere exercise in piety or a display of religious sentimentalism, demonstrating powerful evolutions in contemporary discussions of philosophy, religious tolerance, and the relationship between the church and state. A popular figure that appealed to a heterodox reading public, Rowe addresses many aspects of Dissent throughout her work. Combining close readings of Rowe’s poetry and religious writings with the popular works of her contemporaries, this study explores latitudinarian shifts and discussions of depravity within her religious poetry, the impact of the Clarendon Code and subsequent toleration on her conceptualisation of suffering and imprisonment, as well as her use of ecumenical language throughout her writings. -

A Kind Tho' Vaine Attempt, in Speaking out the Ineffable Doctor Harry More, Late of Christ's Colledge in Cambridge

A BIBLIOGRAPHY OF HENRY MORE compiled by Robert Crocker 1: Manuscripts by, or relating to, Henry More Bibliotheca philosophica Hermetica, Amsterdam A kind tho' vaine attempt, in speaking out the Ineffable Doctor Harry More, Late of Christ's Colledge in Cambridge. That Famous Christian Phylosopher ... To the Ono.ble Sr. Robt. Southwell. at Kings weston neare Bristoll. Farley Castle, Jan. ye 14th. 1687[/8?]. This little biography of More, probably written to commemorate his death, was adapted from a manuscript by Joseph Glanvill, entitled Bensalem, which is now held in the University of Chicago Library. See below. Bodleian Library, Oxford MS Tanner Letters, 42, f. 38: Letter from More to Simon Patrick. MS Tanner Letters, 38, f.115: Letter from More to Archbishop Sancroft. British Library, London Additional MS 23,216: Letters from Henry More to Lady Anne Conway. Most of these were reproduced in Nicolson, Conway Letters. Additional MS 4279 f. 156: A letter from More to John Pell (1665). Additional MS 4276 f. 41: A letter from More to John Sharp (1680). MS Sloane. 235 f. 14-45: Henry More, "Annotationes in C. Bartholini Meta phys." Cambridge University Library MS. Gg.6.11.(F.) f.I-33: Correspondence between H. Hirn and Henry More. MS. Dd.12.32.(G.) f.36-55: Anonymous notes on "Dr. More's Philosophical Collection." Cambridge, Christ's College Library MS. 21: Letters to Henry More from Edmund Elys, Anne Conway, Henry Hallywell, and others. MS. 20: Continuation of Richard Ward's Life (1710) of More. Chicago University Library Bensalem, being A Description of A Catholick & Free Spirit both in Reli gion & Learning.