C:\Myfiles\2002 Proceedings\IACS Proceedings Done.Wpd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

At Villanova. the Program's First Year Of

ATHLETICS ADMINISTRATION ~ QUICK FACTS COVERS ABOUT VILLANOVA 2008 Senior Class . Front and Back Covers Location . .Villanova, Pa. 2007 BIG EAST Tournament . Inside Front Cover Enrollment . .6,240 Glimpse of Villanova . Inside Back Cover Founded . .1842 2008 Schedule . Back Cover President . .Rev. Peter M. Donohue, O.S.A. 2008 SEASON Nickname . .Wildcats Athletics Administration/Quick Facts. 1 Colors . .Blue (PMS 281) and White Roster . 2 Affiliation . .NCAA Division I Season Outlook . 3-4 Conference . .BIG EAST/National Division Head Coach Joe Godri . 5 Assistant Coaches Matt Kirby, Rod Johnson, Chris Madonna. 6 COACHING STAFF Meet the Wildcats . 7-16 Head Coach . .Joe Godri ‘96 VILLANOVA BASEBALL IS... Alma Mater . (New Mexico State ) Record at Villanova . .159-148-3, .518 (6 Years) Tradition . 17 Career Record . .Same Success . 18 Pitching Coach/Recruiting Coordinator . .Matt Kirby (2nd Season) A Regional Power . 19 Third Base Coach/Infield Coach . .Rod Johnson (7th Season) PROGRAM HIGHLIGHTS Hitting Coach . .Chris Madonna (1st Season) Villanova Baseball in the Professional Ranks . 20 Baseball Office . .610-519-4529 Wildcats in the Major Leagues . 21 Head Coach E-Mail . [email protected] Villanova Baseball and the Major League Draft . 22 Assistant Coach E-Mail . [email protected] Villanova Ballpark at Plymouth . 23 BIG EAST Conference . 24 HOME GAMES 2007 YEAR IN REVIEW Stadium . .Villanova Ballpark at Plymouth Accomplishments/Overall Results . 25 Location . .Plymouth Meeting, Pa. (15 minutes from campus) Statistics . 26 Capacity . .750 TEAM HISTORY Surface . .Grass BIG EAST Championship History . 27 Dimensions . .330 LF, 370 LC, 405 CF, 370 RC, 330 RF Postseason History/Head Coaches/Year-by-Year Record. -

Virginia Layout 1

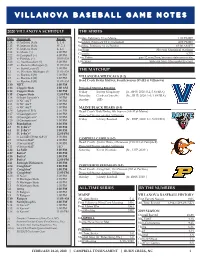

VILLANOVA BASEBALL Game notes 2019 VILLANOVA SCHEDULE THE SERIES Date Opponent Result Friday, February 22 3:00 PM 2.15 vs. Pittsburgh (~) L, 2-7 Saturday, February 23 1:00 PM 2.16 vs. Milwaukee (~) L, 4-7 Sunday, February 24 1:00 PM 2.17 vs. George Mason (~) L, 5-12 Stadium Davenport Field at Disharoon Park 2.22 @ Virginia 3:00 PM Capacity 5,500 2.23 @ Virginia 1:00 PM 2.24 @ Virginia 1:00 PM Live Video ACC Network Extra (watchespn.com) 3.1 vs. Chicago State (!) 2:00 PM Live Stats Sidearm Stats (virginiasports.com) 3.2 vs. St. Bonaventure (!) 12:00 PM 3.3 vs. Chicago State (!) 12:00 PM THE MATCHUP vs. Mount St. Mary’s (!) 3:30 PM 3.5 vs. Western Michigan (!) 2:30 PM VILLANOVA WILDCATS (0-3) 3.6 vs. Northeastern (!) 1:00 PM 3.8 @ Phillies Prospects (exh.) 1:00 PM Head Coach Kevin Mulvey, Third Season (23-75 at Villanova) 3.9 vs. Central Michigan (#) 5:00 PM 3.10 vs. Central Michigan (#) 9:30 AM Starting Rotation 3.12 Navy 3:30 PM Friday Jonathan Rosero (Sr., RHP, 0-1, 9.00 ERA) 3.13 @ Navy 4:00 PM Saturday Jimmy Kingsbury (So., RHP, 0-1, 9.64 ERA) 3.15 La Salle 3:00 PM 3.16 @ La Salle 1:00 PM Sunday Gordon Graceffo (Fr., RHP, 0-1, 4.50 ERA) 3.17 La Salle 12:00 PM 3.19 @ Saint Joseph’s 3:00 PM VIRGINIA CAVALIERS (1-3) 3.22 LIU Brooklyn 3:00 PM Head Coach Brian O’Connor, 16th Season (669-267-2 at Virginia) 3.23 LIU Brooklyn 1:00 PM 3.24 LIU Brooklyn 12:00 PM 3.26 Bucknell 3:30 PM Starting Rotation 3.27 Penn (LB-1) 3:00 PM Friday Griff McGarry (So., RHP, 0-1, 15.20 ERA) 4.2 TBD (Lafayette/Saint Joseph’s) (LB-2) TBD Saturday Noah Murdock (Jr., RHP, 0-0, 4.50 ERA) 4.5 Seton Hall (*) 3:00 PM Sunday Mike Vasil (Fr., RHP, 0-1, 12.27 ERA) 4.6 Seton Hall (*) 1:00 PM 4.7 Seton Hall (*) 12:00 PM 4.9 Saint Joseph’s 3:00 PM 4.12 Georgetown (*) 3:00 PM FIRST PITCHES 4.13 Georgetown (*) 1:00 PM 4.14 Georgetown (*) 1:00 PM • Villanova and Virginia have played on the diamond just four times, and not since 1908 4.18 @ St. -

It's All About the Trucks

Unified sports a hit at PMHS: See page B1 THURSDAY, JUNE 2, 2016 COVERING ALTON, BARNSTEAD, & NEW DURHAM - WWW.SALMONPRESS.COM FREE It’s all about the trucks Touch-a-Truck brings Barnstead community together BY TOM HAGGERTY gine Ford ever made, Contributing Writer 60 horsepower, rather BARNSTEAD — A than the standard 85 sunny late-May Sat- horse of that time. This urday in Barnstead small V-8 was never provided just the right a success because it launch to that commu- lacked power for the nity's first "Touch-a- bigger cars, but it was Truck" day. Scores of a Depression-era effort families gathered at the to save gas and money Barnstead Elementary in a time when fuel was School, where vehicles nine cents a gallon. It's from the highway, po- a perfect size for my lice and fire and res- car. I brought it down cue departments were today so the kids could lined up at the curb, enjoy it." waiting to be climbed That sort of commu- in and on by eager nity spirit was evident youngsters being cap- everywhere at this tured in photographs first-time event. Initi- by their beaming par- ated and organized by ents. Representatives Barnstead Elementary of the departments School Social Worker were on hand to an- Meredith Jacques, the swer questions, help morning's activities familiarize the visitors included a clothing COURTESY PHOTO with the equipment, swap and free pancake At the Capitol and hand out goody breakfast in the school bags and plastic fire gym, coordinated and Members of the Alton Central School eighth grade class pose with copies of The Baysider in front of the US Capitol Building helmets. -

Baseball Head Coach Und.Com Athletics by the Numbers

Mick Doyle Senior • SS Captain Brian Dupra Senior • RHP Captain Cole Johnson Senior • RHP 2009 All-BIG EAST Second Team 2011 Mik Aoki Baseball Head Coach und.com Athletics by the numbers National Championships (11 in football, seven in fencing, three in 26 women’s soccer, two in men’s tennis, one in men’s golf, men’s cross country and women’s basketball) Conference championships won by 8 Irish teams in 2009-10 (BIG EAST, Midwest Fencing Conference) BIG EAST Conference championships 107 won by Notre Dame in 15 seasons of league play All-time Academic All-Americans, 216 second most of any school, including six in 2009-10 Academic All-America honorees since 90 2000; no school has more Irish programs which fi nished their 9 2009-10 campaign ranked Notre Dame teams (out of 22) with a 19 graduation rate of 100% Irish athletic teams that earned a perfect score of 1,000 in the NCAA’s 8 Academic Progress Rate report in 2009-10, second-most in the Football Bowl Subdivision Programs honored by the NCAA for 14 Academic Progress Rate scores in 2009 Irish athletes who received the BIG 3 EAST Scholar-Athlete Sport Excellence Award in 2009-10 Hours of community service complet- 5,631.25 ed by Notre Dame student-athletes during the 2009-10 school year TABLE OF CONTENTS THIS IS NOTRE DAME COACHES Academic Excellence .....................................................................2-3 Head Coach Mik Aoki ................................................................82-83 Sports Medicine .................................................................................4 -

Albuquerque Morning Journal, 07-12-1909 Journal Publishing Company

University of New Mexico UNM Digital Repository Albuquerque Morning Journal 1908-1921 New Mexico Historical Newspapers 7-12-1909 Albuquerque Morning Journal, 07-12-1909 Journal Publishing Company Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/abq_mj_news Recommended Citation Journal Publishing Company. "Albuquerque Morning Journal, 07-12-1909." (1909). https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/ abq_mj_news/3706 This Newspaper is brought to you for free and open access by the New Mexico Historical Newspapers at UNM Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Albuquerque Morning Journal 1908-1921 by an authorized administrator of UNM Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. aft. ALBUQUERQUE MOBNINGt JOURNAL. Vol. 59 THIRTY-FIRS- T YEAR, CXXIII. No. 12. ALBUQUERQUE, NEW MEXICO, MONDAY, JULY 12, 1909, B) Mail eta. Month: Single Coplea, fleota. ttf i arrler O centa m mnath. part i.f th bill, , tariff Delegates fivm limber supply will ever he exhausto. t. lgl-,1- :S II !leee-S- ... It of life and T, bodies, ill a! nivls o llir hiii of the opinion that we willh.it,-ampl- one which th. t ,tii w. 'lie as a ' w ill i ., A "Ul:tlv iii.'. del, gat:,.!!. timber for our needs for an pa rl oi lile Hid not w P.i, they l e- WEST ANXIOUS issued says. s E HAND GAD HITS i ALDRICH SAYS statement iu.lefihU. time for all lime, in fact. gal .1 as s.'lii, t hi eg apart "A canvass t i . mil noted '"Talk commonly indulged in rcRaril-in- "1 run glad to know that all among oniim-rein- l uno thousand bod- the do;, lotion of timber in Hie churches in a wat are adopting the ies - throughout lb. -

Villanova Baseball Game Notes

VILLANOVA BASEBALL GAME NOTES 2020 VILLANOVA SCHEDULE THE SERIES Date Opponent Result Friday, February 28 vs Northeastern 3:00 PM ET 2.14 @ Arizona State L, 1-4 Saturday, February 29 vs Eastern Michigan 11:00 AM ET 2.15 @ Arizona State W, 2-1 Sunday, March 1 vs St. Louis 1:00 PM ET 2.16 @ Arizona State L, 4-6 Monday, March 3 vs Western Michigan 11:00 AM ET 2.21 vs Maine (~) W, 7-2 Stadium North Charlotte Regional Park 2.22 @ Campbell (~) W, 6-2 2.23 vs Purdue (~) L, 1-7 Live Video flobaseball.TV 2.28 vs. Northeastern (!) 3:00 PM Live Stats TBD 2.29 vs. Eastern Michigan (!) 11:00 AM 3.1 vs. Saint Louis (!) 1:00 PM THE MATCHUP 3.3 vs. Western Michigan (!) 11:00 AM 3.6 vs. Bucknell (#) 1:00 PM VILLANOVA WILDCATS (3-3) 3.7 vs. Bucknell (#) 2:30 PM 3.8 vs. Bucknell (#) 11:00 AM Head Coach Kevin Mulvey, Fourth Season (39-113 at Villanova) 3.10 NJIT 3:00 PM 3.13 Coppin State 3:00 AM Projected Starting Rotation 3.14 Coppin State 1:00 PM Friday Jimmy Kingsbury (Jr., RHP, 2020: 1-1, 4.38 ERA) 3.15 Coppin State 12:00 PM Saturday Gordon Graceffo (So., RHP, 2020: 2-0, 1.59 ERA) 3.18 @ Saint Joespeh’s 3:00 PM 3.20 @ NC A&T 7:00 PM Sunday Cole Vanderslice (Fr., RHP, 2020: 0-0, 2.25 ERA) 3.21 @ NC A&T 3:00 PM Tuesday TBD 3.22 @ NC A&T 1:00 PM 3.24 Lafayette (LB-1) 3:00 PM NORTHEASTERN HUSKIES (3-3) - Head Coach Mike Glavine, 5th Season ( 149-132) 3.27 @ Georgetown* 3:00 PM Last Weekend: 3-0 @ South Florida 3.28 @ Georgetown* 2:00 PM 3.29 @ Georgetown* 1:00 PM 3.31 Manhattan 3:30 PM EASTERN MICHIGAN EAGLES (1-6) - Head Coach Eric Roof, 2nd Season (11-43-1) 4.3 St. -

Villanova Baseball Game Notes

VILLANOVA BASEBALL GAME NOTES 2020 VILLANOVA SCHEDULE THE SERIES Date Opponent Result Friday, February 21 vs Maine 1:00 PM ET 2.14 @ Arizona State L, 1-4 Saturday, February 15 vs Campbell 4:00 PM ET 2.15 @ Arizona State W, 2-1 Sunday, February 16 vs Purdue 10:00 AM ET 2.16 @ Arizona State L, 4-6 Stadium Phoenix Municipal Stadium 2.21 vs Maine (~) 1:00 PM Capacity 8,775 2.22 @ Campbell (~) 4:00 PM 2.23 vs Purdue (~) 10:00 AM Live Video pac-12.com/live/arizona-state-university 2.28 vs. Northeastern (!) 3:00 PM Live Stats Sidearm Stats (thesundevils.com) 2.29 vs. Eastern Michigan (!) 11:00 AM 3.1 vs. Saint Louis (!) 1:00 PM THE MATCHUP 3.3 vs. Western Michigan (!) 11:00 AM 3.6 vs. Bucknell (#) 1:00 PM VILLANOVA WILDCATS (1-2) 3.7 vs. Bucknell (#) 2:30 PM 3.8 vs. Bucknell (#) 11:00 AM Head Coach Kevin Mulvey, Fourth Season (37-112 at Villanova) 3.10 NJIT 3:00 PM 3.13 Coppin State 3:00 AM Projected Starting Rotation 3.14 Coppin State 1:00 PM Friday Jimmy Kingsbury (Jr., RHP, 2020: 0-1, 5.68 ERA) 3.15 Coppin State 12:00 PM Saturday Gordon Graceffo (So., RHP, 2020: 1-0, 1.69 ERA) 3.18 @ Saint Joespeh’s 3:00 PM 3.20 @ NC A&T 7:00 PM Sunday TBD 3.21 @ NC A&T 3:00 PM 3.22 @ NC A&T 1:00 PM MAINE BLACK BEARS (0-3) 3.24 Lafayette (LB-1) 3:00 PM Head Coach Nick Derba, 4th Season ( 60-97 at Maine) 3.27 @ Georgetown* 3:00 PM Projected Starter against Villanova 3.28 @ Georgetown* 2:00 PM 3.29 @ Georgetown* 1:00 PM Friday Johnny Baseball (Sr., RHP, 2020: 0-1, 5.00 ERA) 3.31 Manhattan 3:30 PM 4.3 St. -

INDEPENDENCE DAY Parade Application

ECRWSS Eighth graders look back, ahead: See page A2. PRESORT STD U.S. Postage PAID The Baysider Postal Customer The Baysider THURSDAY, JUNE 26, 2008 COVERING ALTON, BARNSTEAD, & NEW DURHAM - THEBAYSIDER.COM FREE Insurance issue resolved? Fire Department Study Committee hears of possible resolution BY BRENDAN BERUBE to the fact that BFRInc. is an Staff Writer autonomous entity, and does BARNSTEAD — Select- not give the town a say in the men’s representative Jim election of its officers. Barnard informed the Fire According to the letter, the Department Study Commit- LGC equates the relationship tee during its June 18 meeting between the town and of a possible resolution to the BFRInc. to the relationship issue of rising insurance between a school district and costs on the buildings and a bus company (which is con- equipment being leased to the tracted to provide a service to town by Barnstead Fire-Res- the district, but functions as a cue, Inc. (BFRInc.). separate entity under its own Explaining that the select- management). men chose to heed the com- Pointing out that the town mittee’s advice last month could save $6,000 a year on in- and send a letter to the Local surance by attaching BFRInc. ■ BRENDAN BERUBE Government Center (LGC) to the LGC policy,Barnard as- “We love you” asking if the LGC would be sured the committee that the This affectionate group of Kindergarten graduates ended a celebration held in honor of their promotion to the first grade at the Alton Central willing to reinstate BFRInc.’s board of selectmen “will do School on June 16 with a performance of “The Good-Bye Song,”made popular by the children’s program “Sharon, Lois, and Bram’s Elephant Show.” policy (which they picked up whatever it takes to get this in 2004, but dropped in 2005 done,” and asked BFRInc.