Country Report Iraq at a Glance: 2006-07

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Investor Guide of Baghdad (English)

THE USAID-TIJARA PROVINCIAL ECONOMIC GROWTH PROGRAM INVESTOR GUIDE OF BAGHDAD NOVEMBER 2011 This report was produced for review by the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID). It was prepared by The Louis Berger Group, Inc. Contract No. 267-C-00-08-00500-00 The USAID-TIJARA PROVINCIAL ECONOMIC GROWTH PROGRAM INVESTOR GUIDE OF BAGHDAD This guide provides information of the procedures required on how to establish a project or any other investment project in Baghdad province. It includes guidance on obtaining licenses and permits as well as other information useful to investors, . DISCLAIMER The author’s views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect the views of the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) or the United States Government. CONTENTS ACRONYMS ............................................................... ii 1. INTRODUCTION......................................................... 1 Background of Baghdad Investment Commission ............................. 1 Geography ........................................................................................ 1 People ............................................... Error! Bookmark not defined. Economy ........................................................................................... 5 Transport and Communications ........................................................ 6 2. THE INVESTMENT ENVIRONMENT .......................... 7 Introduction ....................................................................................... 7 Openness -

Al-Rabee Securities Does They Are Unable to Compete with the Prices of Imported Items

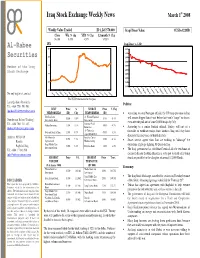

st Iraq Stock Exchange Weekly News March 1 2008 Weekly Value Traded ID 1,245,570,000 Iraqi Dinar Value 1USD=1220ID Close Wk. % chg YTD % Chg 12-month % Chg 36.100 0.45% 4.37% 37.31% ISX Iraqi Dinar vs. USD Al-Rabee 45 1340 1320 Securities 40 1300 1280 35 1260 Member of the Iraq Stock Exchange 1240 30 1220 1200 25 1180 1160 Jan F Mar-07 Apr-07 May- Jun-0 Ju Aug Sep-07 O Nov-0 D Jan Feb-08 20 eb l-07 ct-07 ec-07 J F M A M J J A S O N D J F -0 -07 0 -0 -08 an eb ar pr ay un ul- ug ep ct ov ec an eb 7 7 7 7 7 For any inquiries, contact: -07 -07 -07 -07 -07 -07 07 -07 -07 -07 -07 -07 -08 -08 The ISX Performance for the year Lana Qashani (Research) Politics: Tel: +964 7701 553 503 [email protected] BEST Price % WORST Price % Chg PERFORMERS (ID) Chg PERFORMERS (ID) • According to a top Pentagon official, the US troop presence in Iraq Dar Essalaam Al-Wiaam Financial will remain bigger than it was before last year's "surge" in forces, Nausheruan Baban (Trading) 6.600 11.9% 1.450 -9.4% Investment Bank Investment even after the pull-out of some 20,000 troops by July. Tel: +964 7901 331 492 National Food Ahliya Insurance 1.000 11.1% 1.050 -8.7% • [email protected] Industries According to a senior Turkish official, Turkey will not set a Al-Therar for National Bank of Iraq 1.350 8.0% 0.550 -8.3% timetable to withdraw troops from northern Iraq until they have Agricultural Prod. -

1 Executive Summary Investors in Iraq Face

Executive Summary Investors in Iraq face both tremendous opportunities and significant challenges. The Government of Iraq (GOI) has publicly stated its commitment to attract foreign investment and plans to invest $357 billion in energy, building and services, agriculture, education, transportation, and communications sector projects under its five-year National Development Plan. In 2013 the Iraqi economy grew by 4.2% and investment expenditures in oil production reached $20 billion. Inward FDI grossed $2.5 billion in 2012. Real estate is the largest non-oil area of foreign investment in Iraq. The World Bank ranked Iraq 151 out of 189 economies for “ease of doing business.” Potential investors should prepare to face significant security costs, to navigate cumbersome and confusing bureaucratic procedures, and to expect long payment delays on some GOI contracts. Corruption, delays in customs, unreliable dispute resolution mechanisms, electricity shortages, and lack of access to financing are also common complaints from investors. Internal GOI regulations at times impose unpublicized requirements or procedures that create additional burdens for investors. The GOI currently operates over 192 state-owned enterprises, a legacy of decades of oil-dependent statist economic policy. Insurgent groups, including the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant, an al-Qa’ida offshoot, are increasingly active throughout Iraq. Sectarian and terrorist violence has increased since the beginning of 2013 in Iraq, most notably in the provinces of Baghdad, Ninewa, Salah ad Din, Anbar, and Diyala. The 2006 National Investment Law (NIL) provides a baseline for a modern legal structure to protect foreign and domestic investors in addition to providing investment incentives. -

Investor Guide to Iraq 2019

Republic of Iraq Presidency of Council of Ministers National Investment Commission Investor Guide to Iraq 2019 جمهورية العراق رئاسة مجلس الوزراء Investor Guide to Iraq 2019 Republic of Iraq Presidency of Misters Council National Investment Commission (Investor's Guide to Iraq 2019( www.investpromo.gov.iq Page 0 Investor Guide to Iraq 2019 Dear Investor, Investment opportunities in today's Iraq vary in terms of their type, size, scope, purpose and sector structure. Investors will find the way open for them to establish, operate or develop projects in line with their wishes, and according to the diverse and growing needs of the Iraqi population. The location of Iraq at the center of the world’s trade routes gives it a significant advantage, which combined with the diversity of unique natural resources, helps to provide a decent standard of living. The country's characteristics create many opportunities for investors, suppliers, transporters, developers, producers, manufacturers and financiers who will find many tools that will help them build relationships and establish new projects; to develop markets and establish mutually beneficial business connections. In this document, we provide an overview of detailed information about Iraq as well as many economic statistics and information on legislation that benefits investors; explaining how to invest in Iraq, and the privileges available to investors. Placing this information at your disposal, we would appreciate your opinions and suggestions, and we look forward to working together to implement constructive and fruitful policies for attracting investors who wish to positively contribute to the economic prosperity of Iraq and its people. With sincere appreciation, Dr. -

Appendix 1 7.1.04

APPENDIX I SECTOR: Security and Law Enforcement Since the last report, an additional $1.5 billion in Development Fund for Iraq (DFI) funding has been added to security efforts: $500 million in the revised 2004 Iraqi budget published in early April and $1 billion in funds from the UN escrow account for the Oil for Food program. Of the additional $1.5 billion, $1 billion was added for training, equipping and sustaining Iraqi security forces. Another $377 million was added to support the following three initiatives: the Accelerated Iraqi Reconstruction Program, the Rapid Regional Response Program (R3P) and the Middle Euphrates Program. The remaining $123 million was added to the Commander’s Emergency Response Program (CERP) allowing Coalition field commanders to address humanitarian needs in their region of authority. The additional funds for Iraqi security forces have been applied toward new and emerging requirements as a direct result of the more difficult security situation since early April. As noted in the Executive Summary, Lieutenant General David Petraeus arrived in early June to lead the Office of Security Transition-Iraq (OST-I). At his request the Coalition Provisional Authority (CPA) established the “Iraqi Security Forces Quick Response Program,” a new project that was separately reported and notified on June 24, 2004. This $40 million project will allow OST-I to make a series of diverse, relatively small purchases in support of the Iraqi Armed Forces, the Iraqi National Guard (ING, formerly the Iraqi Civil Defense Corps), Iraqi Police Service, Department of Border Enforcement, and the Facilities Protection Service. This program will be funded out of the IRRF by reallocating $20 million from the Border Enforcement project and $20 million from the Facilities Protection Service. -

Investment Map of Iraq 2019 Republic of Iraq Presidency of Council of Ministers National Investment Commission

Republic of Iraq Presidency of Council of Ministers National Investment Commission Investment Map of Iraq 2019 Republic of Iraq Presidency of Council of Ministers National Investment Commission Investment Map of Iraq 2019 www.investpromo.gov.iq [email protected] Dear investor: Investment opportunities found in Iraq today vary in terms of type, size, scope, sector, and purpose. the door is wide open for all investors who wish to hold investment projects in Iraq,; projects that would meet the growing needs of the Iraqi population in different sectors. In this map, we provide a detailed overview about Iraq, and an outline about each governorate including certain information on each sector. In addition, you will find a list of investment I herby invite you to look at Iraq as opportunities that was classified as per one of the most important places the available investment opportunities in where untapped investment each economic sector in each opportunities are available in various governorate. This updated map includes a fields and where each sector has a number of investment opportunities that crucial need for investment. were presented by the concerned Ministries. Think about the great potentials and We reiterate our efforts to increase the markets of the neighboring economic and investment cooperation countries. Moreover, think about our with all countries of the world through real desire to receive and welcome continuous efforts to stimulate and attract you in Iraq , we are more than ready investments, reconstruction and to cooperate with you In order to development in productive fields with overcome any obstacle we may face. -

Weekly Update October 14.Pub

RECONSTRUCTION WEEKLY UPDATE SeptemberOctober 14, 23, 2005 2005 An Iraqi child reads from the board in her class. USAID partners are supporting the return of children to schools on an accelerated basis following the disruption of war and its aftermath, and are providing the essential teaching and learning resources for students to resume quality learning. Contents: Economic Growth .............................................. 2 Transition Initiatives .......................................... 6 Agriculture......................................................... 3 Disaster Assistance........................................... 7 National Governance......................................... 4 Completed Programs ........................................ 8 Education .......................................................... 5 Financial Summary ........................................... 9 USAID assists Iraqis in reconstructing their country by working with Iraq’s Interim Government. Programs are implemented in coordination with the United Nations, country partners, nongovernmental organizations, and private sector partners. This report highlights USAID’s overall accomplishments and recent reconstruction efforts in Iraq. For more information, please visit www.usaid.gov/iraq. UNITED STATES AGENCY FOR INTERNATIONAL DEVELOPMENT WWW.USAID.GOV ECONOMIC GROWTH October 14, 2005 MAJOR ACCOMPLISHMENTS USAID works with Iraqi institutions to establish an environment for sustainable TO DATE economic growth. Assistance empowers policy makers to formulate -

Special Report – Iraq

IRAQ TRANSITION – 33 Days and Counting… With only 33 days until the June 30 deadline for transferring authority back to the Iraqi people, the Bush Administration has its work cut out for it. Despite the White House’s obsession with Iraq after 9/11, there is still no credible plan for reconstruction and stability. The Center for American Progress continues to update the following “To Do List” to help keep tabs on the wide range of transition challenges facing the Coalition Provisional Authority and Administrator Paul Bremer. Paul Bremer’s To Do List Task Status Come up with plan U.N. special envoy Lakhdar Brahimi is working on plans to for governance of dismantle the US-appointed Governing Council and replace it Iraq with a new body of respected Iraqis, selected through a UN- guided consultative process. The new caretaker government will run the country until elections slated for early next year. The Administration has accepted Brahimi’s proposal, but it remains to be seen which individuals will be asked to serve in the government and appointed to key political positions. Secure new U.N. Negotiations are underway on a draft proposed by the United Security Council Kingdom and the United States. The resolution is instrumental resolution for outlining the international role surrounding the June 30 transition. Some Security Council members, including France and Germany, have expressed serious reservations. The current draft is unclear what ‘sovereignty’ the new Iraqi government will exercise. Specifically in the area of security, it provides no timeline for the international military presence and no details on who the ultimate authority will be regarding the use of force. -

Postwar Iraq's Financial System: Building from Scratch

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Calhoun, Institutional Archive of the Naval Postgraduate School Calhoun: The NPS Institutional Archive Faculty and Researcher Publications Faculty and Researcher Publications 2005 Postwar Iraq's Financial System: Building from Scratch Looney, Robert Middle East Policy, Vol. XII, No. 1, Spring 2005. http://hdl.handle.net/10945/40861 MIDDLE EAST POLICY, VOL. XII, NO. 1, SPRING 2005 POSTWAR IRAQ’S FINANCIAL SYSTEM: BUILDING FROM SCRATCH Robert Looney Dr. Looney is a professor at the Naval Postgraduate School. If I am permitted to dream, Iraq will develop into the Japan of the Middle East.1 – Talib al-Tabatie, chairman, Iraq Stock Exchange The best thing is to overhaul the whole financial system. It’s like when you have a house infested with termites. It’s much easier to knock it down and rebuild than to keep spraying for termites and fixing the holes.2 – Rubar S. Sandi, head, U.S.-Iraq Business Council n the midst of daily reports of suicide Significantly, a large proportion of bombings, insurgents, coalition interim Prime Minister Iyad Allawi’s initial casualties and the relentless toll of address focused on the economic issues Icivilian dead and wounded, any confronting Iraq. Allawi, a Baathist who appraisal of Iraq’s economy has seemed served in the Iraqi intelligence services irrelevant when set against the greater until falling out with the regime and leaving military and security concerns. Yet the Iraq in 1971, cited inflation, unemployment long-run health of the economy will be and weak purchasing power as the main crucial in determining whether Iraq will be economic problems. -

Iraq After ISIS: What to Do Now

April 2018 Iraq After ISIS: What To Do Now Bartle Bull & Douglas Ollivant International Security Last edited on April 23, 2018 at 8:50 a.m. EDT Acknowledgements Disclosure: The authors of this report work for Northern Gulf Partners and Mantid International both of which have �nancial interests in Iraq though neither author has a �nancial interest in who is elected to govern Iraq on May 12th. newamerica.org/international-security/reports/iraq-after-isis-what-do-now/ 2 About the Author(s) Bartle Bull has written from and about Iraq for many publications since 2004. He is an author and founder of Northern Gulf Partners, an Iraq-focused merchant banking �rm. His next book is a history of Iraq. Douglas Ollivant is an ASU Future of War senior fellow at New America. He is managing partner and the senior vice president of Mantid International, LLC. About New America We are dedicated to renewing America by continuing the quest to realize our nation’s highest ideals, honestly confronting the challenges caused by rapid technological and social change, and seizing the opportunities those changes create. About International Security The International Security program aims to provide evidence-based analysis of some of the thorniest questions facing American policymakers and the public. We are focused on South Asia and the Middle East, extremist groups such as ISIS, al Qaeda and allied groups, the proliferation of drones, homeland security, and the activities of U.S. Special Forces and the CIA. newamerica.org/international-security/reports/iraq-after-isis-what-do-now/ -

IRAQ: INVESTMENT CLIMATE 2012 ASSESSMENT INVESTMENT IRAQ: IRAQ Investment Climate Assessment 2012 IRAQ

Public Disclosure Authorized IRAQ: INVESTMENT ASSESSMENT 2012 CLIMATE IRAQ Investment Climate Assessment 2012 IRAQ Investment Climate Public Disclosure Authorized Assessment 2012 Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized 1221366 IRAQ Investment Climate Assessment 2012 Inger Andersen, Vice President Loïc Chiquier, Sector Director Hedi Larbi, Country Director Simon C. Bell, Sector Manager Hooman Dabidian, Task Team Leader Iraq Investment FM 10-16-12.indd 1 10/17/12 3:42 PM Iraq Investment FM 10-16-12.indd 2 10/17/12 3:42 PM iii CONTENTS Abbreviations and Acronyms.......................................................................................................vii Foreword ......................................................................................................................................ix Acknowledgements ......................................................................................................................xi Executive Summary ....................................................................................................................xiii INTRODUCTION .................................................................................................... 1 MAIN IMPEDIMENTS TO PRODUCTIVITY .............................................................. 7 REFORM STATE-OWNED ENTERPRISES .............................................................. 25 STRENGTHEN MARKET GOVERNANCE .............................................................. 37 Corruption....................................................................................................................38 -

The Necessity of Issuing a Corporate Governance Code for the Kurdistan Region

Journal of Finance and Accountancy Volume 18 – January, 2015 The necessity of issuing a corporate governance code for the Kurdistan Region Shivan A.M. Doski University of Duhok ABSTRACT This study proposes to answer a very critical question “Why does the Kurdistan region-Iraq need to pass corporate governance codes for different types of companies and ownership structure” by analyzing theoretically the most important factors leads to issue a corporate governance code for the Kurdistan region. There no laws or regulations for corporate governance in Iraq until now, in spite the issuance of many ministerial orders such as the order from the ministry of industry and minerals in November of 2006, establishing four committees to follow the development of the corporate governance (CG) codes of ethics/conduct and procedures in Iraq, in addition to recommendations from few past scientific research such as ((Al-Ani & Al-Azzawi, 2007: Abdulhakim & Dalloul, 2009: Al-Obeidi, 2011: Karbala center for studies and economic research, 2012: Khudair : 2012), and many other factors, motivate the researcher to propose a corporate governance code in Kurdistan in isolation from Iraq's. Therefore this study focuses on the most influential factors that make the need for Kurdistan corporate governance code (KCGC) inevitable case and must be formed and written. The low level of investor’s protection was one of the most influential variables affecting delay establishing corporate governance code. These reasons divided to nine main categories include (legal aspects, investor’s protection, transparency and disclosure, numerous potential opportunities for investment and trade, vast oil reserve and potential economic hyper growth, safety and security, the socio- cultural aspects, economic freedom and doing business, and lastly corruption).