Postwar Iraq's Financial System: Building from Scratch

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Investor Guide of Baghdad (English)

THE USAID-TIJARA PROVINCIAL ECONOMIC GROWTH PROGRAM INVESTOR GUIDE OF BAGHDAD NOVEMBER 2011 This report was produced for review by the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID). It was prepared by The Louis Berger Group, Inc. Contract No. 267-C-00-08-00500-00 The USAID-TIJARA PROVINCIAL ECONOMIC GROWTH PROGRAM INVESTOR GUIDE OF BAGHDAD This guide provides information of the procedures required on how to establish a project or any other investment project in Baghdad province. It includes guidance on obtaining licenses and permits as well as other information useful to investors, . DISCLAIMER The author’s views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect the views of the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) or the United States Government. CONTENTS ACRONYMS ............................................................... ii 1. INTRODUCTION......................................................... 1 Background of Baghdad Investment Commission ............................. 1 Geography ........................................................................................ 1 People ............................................... Error! Bookmark not defined. Economy ........................................................................................... 5 Transport and Communications ........................................................ 6 2. THE INVESTMENT ENVIRONMENT .......................... 7 Introduction ....................................................................................... 7 Openness -

Financial Futures of the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant: Findings from a RAND Corporation Workshop

Financial Futures of the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant Findings from a RAND Corporation Workshop Colin P. Clarke, Kimberly Jackson, Patrick B. Johnston, Eric Robinson, Howard J. Shatz C O R P O R A T I O N For more information on this publication, visit www.rand.org/t/CF361 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available for this publication. ISBN: 978-0-8330-9739-2 Published by the RAND Corporation, Santa Monica, Calif. © Copyright 2017 RAND Corporation R® is a registered trademark. Cover: images adapted from Reuters and Fotolia. Limited Print and Electronic Distribution Rights This document and trademark(s) contained herein are protected by law. This representation of RAND intellectual property is provided for noncommercial use only. Unauthorized posting of this publication online is prohibited. Permission is given to duplicate this document for personal use only, as long as it is unaltered and complete. Permission is required from RAND to reproduce, or reuse in another form, any of its research documents for commercial use. For information on reprint and linking permissions, please visit www.rand.org/pubs/permissions. The RAND Corporation is a research organization that develops solutions to public policy challenges to help make communities throughout the world safer and more secure, healthier and more prosperous. RAND is nonprofit, nonpartisan, and committed to the public interest. RAND’s publications do not necessarily reflect the opinions of its research clients and sponsors. Support RAND Make a tax-deductible charitable contribution at www.rand.org/giving/contribute www.rand.org Preface The Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (ISIL) has been described as the wealthiest terrorist group in history. -

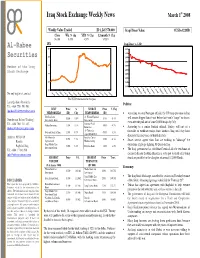

Al-Rabee Securities Does They Are Unable to Compete with the Prices of Imported Items

st Iraq Stock Exchange Weekly News March 1 2008 Weekly Value Traded ID 1,245,570,000 Iraqi Dinar Value 1USD=1220ID Close Wk. % chg YTD % Chg 12-month % Chg 36.100 0.45% 4.37% 37.31% ISX Iraqi Dinar vs. USD Al-Rabee 45 1340 1320 Securities 40 1300 1280 35 1260 Member of the Iraq Stock Exchange 1240 30 1220 1200 25 1180 1160 Jan F Mar-07 Apr-07 May- Jun-0 Ju Aug Sep-07 O Nov-0 D Jan Feb-08 20 eb l-07 ct-07 ec-07 J F M A M J J A S O N D J F -0 -07 0 -0 -08 an eb ar pr ay un ul- ug ep ct ov ec an eb 7 7 7 7 7 For any inquiries, contact: -07 -07 -07 -07 -07 -07 07 -07 -07 -07 -07 -07 -08 -08 The ISX Performance for the year Lana Qashani (Research) Politics: Tel: +964 7701 553 503 [email protected] BEST Price % WORST Price % Chg PERFORMERS (ID) Chg PERFORMERS (ID) • According to a top Pentagon official, the US troop presence in Iraq Dar Essalaam Al-Wiaam Financial will remain bigger than it was before last year's "surge" in forces, Nausheruan Baban (Trading) 6.600 11.9% 1.450 -9.4% Investment Bank Investment even after the pull-out of some 20,000 troops by July. Tel: +964 7901 331 492 National Food Ahliya Insurance 1.000 11.1% 1.050 -8.7% • [email protected] Industries According to a senior Turkish official, Turkey will not set a Al-Therar for National Bank of Iraq 1.350 8.0% 0.550 -8.3% timetable to withdraw troops from northern Iraq until they have Agricultural Prod. -

List of Certain Foreign Institutions Classified As Official for Purposes of Reporting on the Treasury International Capital (TIC) Forms

NOT FOR PUBLICATION DEPARTMENT OF THE TREASURY JANUARY 2001 Revised Aug. 2002, May 2004, May 2005, May/July 2006, June 2007 List of Certain Foreign Institutions classified as Official for Purposes of Reporting on the Treasury International Capital (TIC) Forms The attached list of foreign institutions, which conform to the definition of foreign official institutions on the Treasury International Capital (TIC) Forms, supersedes all previous lists. The definition of foreign official institutions is: "FOREIGN OFFICIAL INSTITUTIONS (FOI) include the following: 1. Treasuries, including ministries of finance, or corresponding departments of national governments; central banks, including all departments thereof; stabilization funds, including official exchange control offices or other government exchange authorities; and diplomatic and consular establishments and other departments and agencies of national governments. 2. International and regional organizations. 3. Banks, corporations, or other agencies (including development banks and other institutions that are majority-owned by central governments) that are fiscal agents of national governments and perform activities similar to those of a treasury, central bank, stabilization fund, or exchange control authority." Although the attached list includes the major foreign official institutions which have come to the attention of the Federal Reserve Banks and the Department of the Treasury, it does not purport to be exhaustive. Whenever a question arises whether or not an institution should, in accordance with the instructions on the TIC forms, be classified as official, the Federal Reserve Bank with which you file reports should be consulted. It should be noted that the list does not in every case include all alternative names applying to the same institution. -

Corruption Worse Than ISIS: Causes and Cures Cures for Iraqi Corruption

Corruption Worse Than ISIS: Causes and Cures Cures for Iraqi Corruption Frank R. Gunter Professor of Economics, Lehigh University Advisory Council Member, Iraq Britain Business Council “Corruption benefits the few at the expense of the many; it delays and distorts economic development, pre-empts basic rights and due process, and diverts resources from basic services, international aid, and whole economies. Particularly where state institutions are weak, it is often linked to violence.” (Johnston 2006 as quoted by Allawi 2020) Like sand after a desert storm, corruption permeates every corner of Iraqi society. According to Transparency International (2021), Iraq is not the most corrupt country on earth – that dubious honor is a tie between Somalia and South Sudan – but Iraq is in the bottom 12% ranking 160th out of the 180 countries evaluated. With respect to corruption, Iraq is tied with Cambodia, Chad, Comoros, and Eritrea. Corruption in Iraq extends from the ministries in Baghdad to police stations and food distribution centers in every small town. (For excellent overviews of the range and challenges of corruption in Iraq, see Allawi 2020 and Looney 2008.) While academics may argue that small amounts of corruption act as a “lubricant” for government activities, the large scale of corruption in Iraq undermines private and public attempts to achieve a better life for the average Iraqi. A former Iraqi Minister of Finance and a Governor of the Central Bank both stated that the deleterious impact of corruption was worse than that of the insurgency (Minister of Finance 2005). This is consistent with the Knack and Keefer study (1995, Table 3) that showed that corruption has a greater adverse impact on economic growth than political violence. -

Central Bank of Iraq Financial Statements 31

CENTRAL BANK OF IRAQ FINANCIAL STATEMENTS 31 DECEMBER 2018 t CENTRAL BANK OF IRAQ STATEMENT OF COMPREHENSIVE INCOME YEAR ENDED 31 DECEMBER 2018 2018 2017 Notes IQD million IQD million REVENUES Interest income 25 2,046,740 1,479,171 Interest expense 26 (144,251) (51,285) Net interest income 1,902,489 1,427,886 Net fees and commissions income 27 427,849 364,418 Gold revaluation (loss) gain 22 (39,217) 476,668 Foreign currency translation (loss) gain (580,035) 1,891,097 Other income 34,301 25,022 Gross profit 1,745,387 4,185,091 EXPENSES Employees’ expenses (49,914) (34,653) General and administrative expenses (103,582) (57,735) Depreciation and amortization 10,11 (12,076) (17,930) Allowance for credit losses (1,089) (42,393) Impairment losses on lands 10 - (20,104) PROFIT FOR THE YEAR 1,578,726 4,012,276 Add: Other comprehensive income items will not be classified to statement of income in subsequent periods Unrealized gains from lands and buildings revaluation - 212,056 Total of other comprehensive income items - 212,056 TOTAL COMPREHENSIVE INCOME FOR THE YEAR 1,578,726 4,224,332 The attached notes 1 to 35 form part of these financial statements. -2- CENTRAL BANK OF IRAQ STATEMENT OF CHANGE IN EQUITY YEAR ENDED 31 DECEMBER 2018 Lands and Gold buildings General Emergency revaluation revaluation Retained Capital reserve reserve reserve reserve earnings Total IQD IQD IQD IQD IQD IQD IQD Notes million million million million million million million Balance at 1 January 2018 1,000,000 477,425 1,089,690 109,045 212,056 3,535,608 6,423,824 Effect -

Iraq, August 2006

Library of Congress – Federal Research Division Country Profile: Iraq, August 2006 COUNTRY PROFILE: IRAQ August 2006 COUNTRY Formal Name: Republic of Iraq (Al Jumhuriyah al Iraqiyah). Short Form: Iraq. Term for Citizen(s): Iraqi(s). Click to Enlarge Image Capital: Baghdad. Major Cities (in order of population size): Baghdad, Mosul (Al Mawsil), Basra (Al Basrah), Arbil (Irbil), Kirkuk, and Sulaymaniyah (As Sulaymaniyah). Independence: October 3, 1932, from the British administration established under a 1920 League of Nations mandate. Public Holidays: New Year’s Day (January 1) and the overthrow of Saddam Hussein (April 9) are celebrated on fixed dates, although the latter has lacked public support since its declaration by the interim government in 2003. The following Muslim religious holidays occur on variable dates according to the Islamic lunar calendar, which is 11 days shorter than the Gregorian calendar: Eid al Adha (Feast of the Sacrifice), Islamic New Year, Ashoura (the Shia observance of the martyrdom of Hussein), Mouloud (the birth of Muhammad), Leilat al Meiraj (the ascension of Muhammad), and Eid al Fitr (the end of Ramadan). Flag: The flag of Iraq consists of three equal horizontal bands of red (top), white, and black with three green, five-pointed stars centered in the white band. The phrase “Allahu Akbar” (“God Is Great”) also appears in Arabic script in the white band with the word Allahu to the left of the center star and the word Akbar to the right of that star. Click to Enlarge Image HISTORICAL BACKGROUND Early History: Contemporary Iraq occupies territory that historians regard as the site of the earliest civilizations of the Middle East. -

Iraq Study Group Consultations

CENTER FOR THE STUDY OF THE PRESIDENCY IRAQ STUDY GROUP Iraq Study Group Consultations (* denotes meeting took place in Iraq) Iraqi Officials and Representatives * Jalal Talabani - President * Tareq al-Hashemi - Vice President * Adil Abd al-Mahdi - Vice President * Nouri Kamal al-Maliki - Prime Minister * Salaam al-Zawbai - Deputy Prime Minister * Barham Salih - Deputy Prime Minister * Mahmoud al-Mashhadani - Speaker of the Parliament * Mowaffak al-Rubaie - National Security Advisor * Jawad Kadem al-Bolani - Minister of Interior * Abdul Qader Al-Obeidi - Minister of Defense * Hoshyar Zebari - Minister of Foreign Affairs * Bayan Jabr - Minister of Finance * Hussein al-Shahristani - Minster of Oil * Karim Waheed - Minister of Electricity * Akram al-Hakim - Minister of State for National Reconciliation Affairs * Mithal al-Alusi - Member, High Commission on National Reconciliation * Ayad Jamal al-Din - Member, High Commission on National Reconciliation * Ali Khalifa al-Duleimi - Member, High Commission on National Reconciliation * Sami al-Ma'ajoon - Member, High Commission on National Reconciliation * Muhammad Ahmed Mahmoud - Member, Commission on National Reconciliation * Wijdan Mikhael - Member, High Commission on National Reconciliation Lt. General Nasir Abadi - Deputy Chief of Staff of the Iraqi Joint Forces * Adnan al-Dulaimi - Head of the Tawafuq list Ali Allawi - Former Minister of Finance * Sheik Najeh al-Fetlawi - representative of Muqtada al-Sadr * Abd al-Aziz al-Hakim - Shia Coalition Leader * Sheik Maher al-Hamraa - Ayat Allah -

1 Executive Summary Investors in Iraq Face

Executive Summary Investors in Iraq face both tremendous opportunities and significant challenges. The Government of Iraq (GOI) has publicly stated its commitment to attract foreign investment and plans to invest $357 billion in energy, building and services, agriculture, education, transportation, and communications sector projects under its five-year National Development Plan. In 2013 the Iraqi economy grew by 4.2% and investment expenditures in oil production reached $20 billion. Inward FDI grossed $2.5 billion in 2012. Real estate is the largest non-oil area of foreign investment in Iraq. The World Bank ranked Iraq 151 out of 189 economies for “ease of doing business.” Potential investors should prepare to face significant security costs, to navigate cumbersome and confusing bureaucratic procedures, and to expect long payment delays on some GOI contracts. Corruption, delays in customs, unreliable dispute resolution mechanisms, electricity shortages, and lack of access to financing are also common complaints from investors. Internal GOI regulations at times impose unpublicized requirements or procedures that create additional burdens for investors. The GOI currently operates over 192 state-owned enterprises, a legacy of decades of oil-dependent statist economic policy. Insurgent groups, including the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant, an al-Qa’ida offshoot, are increasingly active throughout Iraq. Sectarian and terrorist violence has increased since the beginning of 2013 in Iraq, most notably in the provinces of Baghdad, Ninewa, Salah ad Din, Anbar, and Diyala. The 2006 National Investment Law (NIL) provides a baseline for a modern legal structure to protect foreign and domestic investors in addition to providing investment incentives. -

Investor Guide to Iraq 2019

Republic of Iraq Presidency of Council of Ministers National Investment Commission Investor Guide to Iraq 2019 جمهورية العراق رئاسة مجلس الوزراء Investor Guide to Iraq 2019 Republic of Iraq Presidency of Misters Council National Investment Commission (Investor's Guide to Iraq 2019( www.investpromo.gov.iq Page 0 Investor Guide to Iraq 2019 Dear Investor, Investment opportunities in today's Iraq vary in terms of their type, size, scope, purpose and sector structure. Investors will find the way open for them to establish, operate or develop projects in line with their wishes, and according to the diverse and growing needs of the Iraqi population. The location of Iraq at the center of the world’s trade routes gives it a significant advantage, which combined with the diversity of unique natural resources, helps to provide a decent standard of living. The country's characteristics create many opportunities for investors, suppliers, transporters, developers, producers, manufacturers and financiers who will find many tools that will help them build relationships and establish new projects; to develop markets and establish mutually beneficial business connections. In this document, we provide an overview of detailed information about Iraq as well as many economic statistics and information on legislation that benefits investors; explaining how to invest in Iraq, and the privileges available to investors. Placing this information at your disposal, we would appreciate your opinions and suggestions, and we look forward to working together to implement constructive and fruitful policies for attracting investors who wish to positively contribute to the economic prosperity of Iraq and its people. With sincere appreciation, Dr. -

Economic Policy and Prospects in Iraq

No. 04-1 Economic Policy and Prospects in Iraq Christopher Foote, William Block, Keith Crane, and Simon Gray Abstract: This paper describes the Coalition Provisional Authority’s attempts to stabilize and reform Iraq’s economy along market lines. It argues that while security concerns remain serious, Iraq’s economy has not been crippled by violence. However, sustained economic growth will depend on whether Iraq’s future leaders pursue the pro-market approaches the Coalition has advocated. If the Iraqi economy is to reach its potential, it will need to go even farther than the Coalition did, implementing reforms the Coalition did not pursue because of security concerns. ______________________________________________________________________________________ Christopher Foote is a Senior Economist, Federal Reserve Bank of Boston, Boston, Massachusetts. William Block is an Economist, U.S. Department of the Treasury, Washington, D.C. Keith Crane is a Senior Economist, the RAND Corporation, Arlington, Virginia, office. Simon Gray is Adviser to the Governor, Bank of England, London, United Kingdom. All four of the authors worked at the Coalition Provisional Authority, Baghdad, Iraq. Their e-mail addresses are <[email protected]>, <[email protected]>, <[email protected]>, and <[email protected]>, respectively. This paper is available on the web site of the Federal Reserve Bank of Boston at http://www.bos.frb.org/economic/ppdp/index.htm and is forthcoming in the Journal of Economic Perspectives, 2004. The views expressed in this paper are solely those of the authors and do not reflect official positions of the Coalition Provisional Authority, the U.S. Treasury, the Bank of England, the U.S. -

After Saddam: Prewar Planning and the Occupation of Iraq, MG-642-A, Nora Bensahel, Olga Oliker, Keith Crane, Richard R

THE ARTS This PDF document was made available from www.rand.org as CHILD POLICY a public service of the RAND Corporation. CIVIL JUSTICE EDUCATION Jump down to document ENERGY AND ENVIRONMENT 6 HEALTH AND HEALTH CARE INTERNATIONAL AFFAIRS The RAND Corporation is a nonprofit research NATIONAL SECURITY POPULATION AND AGING organization providing objective analysis and PUBLIC SAFETY effective solutions that address the challenges facing SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY the public and private sectors around the world. SUBSTANCE ABUSE TERRORISM AND HOMELAND SECURITY Support RAND TRANSPORTATION AND INFRASTRUCTURE Purchase this document WORKFORCE AND WORKPLACE Browse Books & Publications Make a charitable contribution For More Information Visit RAND at www.rand.org Explore the RAND Arroyo Center View document details Limited Electronic Distribution Rights This document and trademark(s) contained herein are protected by law as indicated in a notice appearing later in this work. This electronic representation of RAND intellectual property is provided for non-commercial use only. Unauthorized posting of RAND PDFs to a non-RAND Web site is prohibited. RAND PDFs are protected under copyright law. Permission is required from RAND to reproduce, or reuse in another form, any of our research documents for commercial use. For information on reprint and linking permissions, please see RAND Permissions. This product is part of the RAND Corporation monograph series. RAND monographs present major research findings that address the challenges facing the public and private sectors. All RAND monographs undergo rigorous peer review to ensure high standards for research quality and objectivity. After Saddam Prewar Planning and the Occupation of Iraq Nora Bensahel, Olga Oliker, Keith Crane, Richard R.