Multiracialism and Politics of Regulating Ethnic Relations in Singapore

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Why Are Gender Reforms Adopted in Singapore? Party Pragmatism and Electoral Incentives* Netina Tan

Why Are Gender Reforms Adopted in Singapore? Party Pragmatism and Electoral Incentives* Netina Tan Abstract In Singapore, the percentage of elected female politicians rose from 3.8 percent in 1984 to 22.5 percent after the 2015 general election. After years of exclusion, why were gender reforms adopted and how did they lead to more women in political office? Unlike South Korea and Taiwan, this paper shows that in Singapore party pragmatism rather than international diffusion of gender equality norms, feminist lobbying, or rival party pressures drove gender reforms. It is argued that the ruling People’s Action Party’s (PAP) strategic and electoral calculations to maintain hegemonic rule drove its policy u-turn to nominate an average of about 17.6 percent female candidates in the last three elections. Similar to the PAP’s bid to capture women voters in the 1959 elections, it had to alter its patriarchal, conservative image to appeal to the younger, progressive electorate in the 2000s. Additionally, Singapore’s electoral system that includes multi-member constituencies based on plurality party bloc vote rule also makes it easier to include women and diversify the party slate. But despite the strategic and electoral incentives, a gender gap remains. Drawing from a range of public opinion data, this paper explains why traditional gender stereotypes, biased social norms, and unequal family responsibilities may hold women back from full political participation. Keywords: gender reforms, party pragmatism, plurality party bloc vote, multi-member constituencies, ethnic quotas, PAP, Singapore DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.5509/2016892369 ____________________ Netina Tan is an assistant professor of political science at McMaster University. -

Ang Mo Kio Information Kit

Ang Mo Kio Information Kit Version 2.0 November 2014 1 Table of Content Table of Content Page A. General - Table of Content 2 - System map 3 B. Station Information - Station Contacts & Overview 4 - Taxi & General Contacts 5 - Station Layout 6-7 - Locality Map 8 - Bus Services (By Bus Stop) 9 - Places of Interest 10 - Train Service Disruption Leaflet 11-12 2 3 Station Overview Station Contact Points Contacts Duty SM Hand phone 9838 9047 Passenger Service Center 6767 3313 EXIT: Exit A & D: Ang Mo Kio Ave 3 Exit B: Ang Mo Kio Ave 8 Exit C:Link Way to AMK HUB ( Bus Interchange) LIFT: Lift 1:Paid Area (North Bound) Lift 2: Paid Area (South Bound) Lift 3: Free Area (AMK HUB & Bus Interchange) PLATFORM North Bound (towards Jurong East ) Line 4 –Platform A South Bound (towards Marine Bay / Marina South Pier): Line 5 –Platform B 4 Taxi & General Contacts Nearby Taxi Stand Road Via Exit B AM K Ave 8 Exit B AMK HUB AMK Ave 3 Exit C Taxi Services Booking number SMRT Taxis 6555 8888 Comfort & City Cab 6552 1111 Trans Cab 6555 3333 Premier Taxis 6363 6888 Hotline Contact SMRT Hotline 1800 336 8900 SMRT Press Contact 9822 0902 TransitLink Hotline 1800 225 5663 Transcom Hotline 1800 842 0000 SMRT Online Feedback: www.smrt.com.sg/feedback.aspx 5 Notices and manpower deployment at Concourse UNDERPASS TO BUS To Free Bus Service at Bus Bridging Bus Stop INTERCHANGE ANG MO KIO STN TEL. BOOTHS S S Exit B Service TLSO Gate ESC ESC ESC S Staircase 104 201 202 203 103 ESC 105 Exit C S ExitA Free PaidPaid FreeArea Info Booth Area Area Wide Area Gate ESC 106 102 101 Staircase S SHOPS Exit D GTMs TVM ROOM LEGEND: S Location of Sign PUBLIC TOILETS Station Staff CST Member Notices and manpower deployment at Platform DEPLOYMENT PLATFORM : 4 MEN To attend to both platform LEGEND: Station Staff CST Member Locality Map sbs Q Pt 2 sbs Q Pt 1 Bus Stop: 54399 Bus Stop: 54391 FBS FBS Bus Service No Bus Service No 50,128,159,265 50,128,159,265 T Bus Stop: 54261 Bus Stop: 54269 FBS @ Bus Interchange Bus Stop: Bus Service No. -

1 Singapore's Dominant Party System

Tan, Kenneth Paul (2017) “Singapore’s Dominant Party System”, in Governing Global-City Singapore: Legacies and Futures after Lee Kuan Yew, Routledge 1 Singapore’s dominant party system On the night of 11 September 2015, pundits, journalists, political bloggers, aca- demics, and others in Singapore’s chattering classes watched in long- drawn amazement as the media reported excitedly on the results of independent Singa- pore’s twelfth parliamentary elections that trickled in until the very early hours of the morning. It became increasingly clear as the night wore on, and any optimism for change wore off, that the ruling People’s Action Party (PAP) had swept the votes in something of a landslide victory that would have puzzled even the PAP itself (Zakir, 2015). In the 2015 general elections (GE2015), the incumbent party won 69.9 per cent of the total votes (see Table 1.1). The Workers’ Party (WP), the leading opposition party that had five elected members in the previous parliament, lost their Punggol East seat in 2015 with 48.2 per cent of the votes cast in that single- member constituency (SMC). With 51 per cent of the votes, the WP was able to hold on to Aljunied, a five-member group representation constituency (GRC), by a very slim margin of less than 2 per cent. It was also able to hold on to Hougang SMC with a more convincing win of 57.7 per cent. However, it was undoubtedly a hard defeat for the opposition. The strong performance by the PAP bucked the trend observed since GE2001, when it had won 75.3 per cent of the total votes, the highest percent- age since independence. -

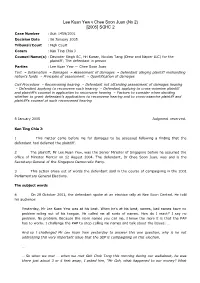

Lee Kuan Yew V Chee Soon Juan (No 2)

Lee Kuan Yew v Chee Soon Juan (No 2) [2005] SGHC 2 Case Number : Suit 1459/2001 Decision Date : 06 January 2005 Tribunal/Court : High Court Coram : Kan Ting Chiu J Counsel Name(s) : Davinder Singh SC, Hri Kumar, Nicolas Tang (Drew and Napier LLC) for the plaintiff; The defendant in person Parties : Lee Kuan Yew — Chee Soon Juan Tort – Defamation – Damages – Assessment of damages – Defendant alleging plaintiff mishandling nation's funds – Principles of assessment – Quantification of damages Civil Procedure – Reconvening hearing – Defendant not attending assessment of damages hearing – Defendant applying to reconvene such hearing – Defendant applying to cross-examine plaintiff and plaintiff's counsel in application to reconvene hearing – Factors to consider when deciding whether to grant defendant's applications to reconvene hearing and to cross-examine plaintiff and plaintiff's counsel at such reconvened hearing 6 January 2005 Judgment reserved. Kan Ting Chiu J: 1 This matter came before me for damages to be assessed following a finding that the defendant had defamed the plaintiff. 2 The plaintiff, Mr Lee Kuan Yew, was the Senior Minister of Singapore before he assumed the office of Minister Mentor on 12 August 2004. The defendant, Dr Chee Soon Juan, was and is the Secretary-General of the Singapore Democratic Party. 3 This action arose out of words the defendant said in the course of campaigning in the 2001 Parliamentary General Elections. The subject words 4 On 28 October 2001, the defendant spoke at an election rally at Nee Soon Central. He told his audience: Yesterday, Mr Lee Kuan Yew was at his best. -

Lee Kuan Yew Continue to flow As Life Returns to Normal at a Market at Toa Payoh Lorong 8 on Wednesday, Three Days After the State Funeral Service

TODAYONLINE.COM WE SET YOU THINKING SUNDAY, 5 APRIL 2015 SPECIAL EDITION MCI (P) 088/09/2014 The tributes to the late Mr Lee Kuan Yew continue to flow as life returns to normal at a market at Toa Payoh Lorong 8 on Wednesday, three days after the State Funeral Service. PHOTO: WEE TECK HIAN REMEMBERING MR LEE KUAN YEW SPECIAL ISSUE 2 REMEMBERING LEE KUAN YEW Tribute cards for the late Mr Lee Kuan Yew by the PCF Sparkletots Preschool (Bukit Gombak Branch) teachers and students displayed at the Chua Chu Kang tribute centre. PHOTO: KOH MUI FONG COMMENTARY Where does Singapore go from here? died a few hours earlier, he said: “I am for some, more bearable. Servicemen the funeral of a loved one can tell you, CARL SKADIAN grieved beyond words at the passing of and other volunteers went about their the hardest part comes next, when the DEPUTY EDITOR Mr Lee Kuan Yew. I know that we all duties quietly, eiciently, even as oi- frenzy of activity that has kept the mind feel the same way.” cials worked to revise plans that had busy is over. I think the Prime Minister expected to be adjusted after their irst contact Alone, without the necessary and his past week, things have been, many Singaporeans to mourn the loss, with a grieving nation. fortifying distractions of a period of T how shall we say … diferent but even he must have been surprised Last Sunday, about 100,000 people mourning in the company of others, in Singapore. by just how many did. -

Transcript of a Press Conference Given by the Prime Minister of Singapore, Mr. Lee Kuan Yew, at Broadcasting House, Singapore, A

1 TRANSCRIPT OF A PRESS CONFERENCE GIVEN BY THE PRIME MINISTER OF SINGAPORE, MR. LEE KUAN YEW, AT BROADCASTING HOUSE, SINGAPORE, AT 1200 HOURS ON MONDAY 9TH AUGUST, 1965. Question: Mr. Prime Minister, after these momentous pronouncements, what most of us of the foreign press would be interested to learn would be your attitude towards Indonesia, particularly in the context of Indonesian confrontation, and how you view to conduct relations with Indonesia in the future as an independent, sovereign nation. Mr. Lee: I would like to phrase it most carefully because this is a delicate matter. But I think I can express my attitude in this way: We want to be friends with Indonesia. We have always wanted to be friends with Indonesia. We would like to settle any difficulties and differences with Indonesia. But we must survive. We have a right to survive. And, to survive, we must be sure that we cannot be just overrun. You know, invaded by armies or knocked out by rockets, if they have rockets -- which they have, ground-to-air. I'm not sure whether they lky\1965\lky0809b.doc 2 have ground-to-ground missiles. And, what I think is also important is we want, in spite of all that has happened -- which I think were largely ideological differences between us and the former Central Government, between us and the Alliance Government -- we want to-operate with them, on the most fair and equal basis. The emphasis is co-operate. We need them to survive. Our water supply comes from Johore. Our trade, 20-odd per cent -- over 20 per cent; I think about 24 per cent -- with Malaya, and about 4 to 5 per cent with Sabah and Sarawak. -

Constitutional Documents of All Tcountries in Southeast Asia As of December 2007, As Well As the ASEAN Charter (Vol

his three volume publication includes the constitutional documents of all Tcountries in Southeast Asia as of December 2007, as well as the ASEAN Charter (Vol. I), reports on the national constitutions (Vol. II), and a collection of papers on cross-cutting issues (Vol. III) which were mostly presented at a conference at the end of March 2008. This collection of Constitutional documents and analytical papers provides the reader with a comprehensive insight into the development of Constitutionalism in Southeast Asia. Some of the constitutions have until now not been publicly available in an up to date English language version. But apart from this, it is the first printed edition ever with ten Southeast Asian constitutions next to each other which makes comparative studies much easier. The country reports provide readers with up to date overviews on the different constitutional systems. In these reports, a common structure is used to enable comparisons in the analytical part as well. References and recommendations for further reading will facilitate additional research. Some of these reports are the first ever systematic analysis of those respective constitutions, while others draw on substantial literature on those constitutions. The contributions on selected issues highlight specific topics and cross-cutting issues in more depth. Although not all timely issues can be addressed in such publication, they indicate the range of questions facing the emerging constitutionalism within this fascinating region. CONSTITUTIONALISM IN SOUTHEAST ASIA Volume 2 Reports on National Constitutions (c) Copyright 2008 by Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung, Singapore Editors Clauspeter Hill Jőrg Menzel Publisher Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung 34 Bukit Pasoh Road Singapore 089848 Tel: +65 6227 2001 Fax: +65 6227 2007 All rights reserved. -

Deliberative Rhetoric in Electoral Authoritarian Regimes: a Case Study of Singapore

Political Science 4995: Honour’s Thesis Deliberative Rhetoric in Electoral Authoritarian Regimes: A Case Study of Singapore Nicolette Stuart 001158635 Dr. von Heyking University of Lethbridge April 2015 Table of Contents INTRODUCTION Introduction ......................................................................................................................................................... 1 CHAPTER ONE Shaping the Audience with the Language of Politics ........................................................................................... 4 CHAPTER TWO Singapore: Testing Aristotle’s Theory of “Regime Mixology” ............................................................................ 27 CHAPTER THREE Aristotle’s Framework for Rhetoric: The Singapore Equation ............................................................................ 52 CONCLUSION Conclusion .......................................................................................................................................................... 75 BIBLIOGRAPHY Bibliography ....................................................................................................................................................... 79 1 Introduction The power of language is often overlooked despite its influence on human interaction. Perhaps the nature of communication as pervasive in the lives of humans makes language less notable. The seemingly natural use of communication, however, does not negate the ability of language to compel human action. Political scientists -

LUI Pui Shan Betsy

The University of Hong Kong Department of Social Work & Social Administration Overseas Fieldwork Placement - Singapore Student’s Summary Report 3 June - 9 August 2019 LUI Pui Shan Betsy Program of Study: Master of Social Work (Part-time) Agency Name: AMKFSC Community Services Ltd. - Cheng San Family Service Centre Duration of Placement: 3 June - 9 August 2019 Introduction of the Placement Agency Social, Cultural, Context of the Country of the Service Agency Singapore has a very similar international status as Hong Kong, which is a well developed country with stable economic growth ranking the 3rd highest GDP per capita. Singapore is a multicultural country with citizens from different backgrounds. English, Mandarin, Malay and Tamil are the four common languages used in this country. Nearly all the residents could speak at least two languages. The government of Singapore is highly aware of the living standard of the residents. Housing, education, healthcare services and personal safety are the priorities of the government. In order to enhance the cultural integration and harmony, the government has implemented different policies to increase the acceptance level of residents in embracing different cultures. For example, for each residential building, the government has set a fixed percentage of flats would be given to a particular ethnic group. Thus, people from various ethnicities could communicate and know each other in the same community. The social welfare system of Singapore believes that family is the basic yet the most important unit in the community. The government therefore encourages the establishment of family 1 service centers in different areas in order to tackle family issues, and provide appropriate tangible and emotional support to the residents in the community. -

Transparency and Authoritarian Rule in Southeast Asia

TRANSPARENCY AND AUTHORITARIAN RULE IN SOUTHEAST ASIA The 1997–98 Asian economic crisis raised serious questions for the remaining authoritarian regimes in Southeast Asia, not least the hitherto outstanding economic success stories of Singapore and Malaysia. Could leaders presiding over economies so heavily dependent on international capital investment ignore the new mantra among multilateral financial institutions about the virtues of ‘transparency’? Was it really a universal functional requirement for economic recovery and advancement? Wasn’t the free flow of ideas and information an anathema to authoritarian rule? In Transparency and Authoritarian Rule in Southeast Asia Garry Rodan rejects the notion that the economic crisis was further evidence that ulti- mately capitalism can only develop within liberal social and political insti- tutions, and that new technology necessarily undermines authoritarian control. Instead, he argues that in Singapore and Malaysia external pres- sures for transparency reform were, and are, in many respects, being met without serious compromise to authoritarian rule or the sanctioning of media freedom. This book analyses the different content, sources and significance of varying pressures for transparency reform, ranging from corporate dis- closures to media liberalisation. It will be of equal interest to media analysts and readers keen to understand the implications of good governance debates and reforms for democratisation. For Asianists this book offers sharp insights into the process of change – political, social and economic – since the Asian crisis. Garry Rodan is Director of the Asia Research Centre, Murdoch University, Australia. ROUTLEDGECURZON/CITY UNIVERSITY OF HONG KONG SOUTHEAST ASIAN STUDIES Edited by Kevin Hewison and Vivienne Wee 1 LABOUR, POLITICS AND THE STATE IN INDUSTRIALIZING THAILAND Andrew Brown 2 ASIAN REGIONAL GOVERNANCE: CRISIS AND CHANGE Edited by Kanishka Jayasuriya 3 REORGANISING POWER IN INDONESIA The politics of oligarchy in an age of markets Richard Robison and Vedi R. -

ANG MO KIO Town Map

ANG MO KIO Town Map ANG MO KIO ROAD L E N T G A O A N N R K G M O A K I V O E N A S N T U G R E E E T A U N G M H 6 O C 5 M O K 4 6 I O T A E E R N Proposed T S G C Health & K I O E Medical Care M N O Chinese O Temple T Ang Mo Kio I S K T Y Police Divisional R A R I E O Headquarter/ Proposed N E A Ang Mo Kio North T Funeral G Ang Mo Kio S Castle L Neighbourhood T Parlour Green Fire Station Nuovo Police Centre R Complex Seasons 6 E E Park 2 T 6 Anderson Primary 3 Ang Mo Kio - School E LENTOR Thye Hua Kwan VENU 9 A MRT STATION E Far Horizon Hospital KIO TEL (u/c) Gardens X Yio Chu kang MO Sports Hall P Yio Chu Kang R A Stadium N E G G YIO CHU KANG N Presbyterian A S The Calrose MRT STATION High School M S Yio Chu Kang Yio Chu Kang O Yio Chu Kang Bus Interchange Swimming W Community Yio Chu Kang Complex A M Club Gardens N A O G The Park Grassroots Y Club Chinese Yio Chu Kang Temples K Squash & Tennis Centre I O Neighbourhood M Centre Nanyang O 1 Petrol 6 Polytechnic REET ST Station K A Yio Chu Kang Yio Chu Kang Anderson Serangoon I N Secondary O Junior College G School BEACON K I O Neighbourhood Park ITE College Central O I A K A N V E Ang Mo Kio Avenue 5 Park Connector G M O N U E Mayflower Primary Font: Arial Narrow / Ragular, Futura / Medium 5 School Mayflower A (Holding) Primary Grandeur 8 A Proposed N School N C93 M61 Y27 K7 C0 M15 Y100 K0 Place of G Anderson G The A (Under upgrading) Worship Secondary V Ang Mo Kio E Panorama School N Public U Library E M NG O ANG MO KIO CENTRAL 3 M A M M O K O A Ang Mo Kio O I O Polyclinic N CHIJ G Church Neighbourhood NG S M A K St. -

Ministry of Health List of Approved Providers for Antigen Rapid Testing for COVID-19 at Offsite Premises List Updated As at 9 Jul 2021

Ministry of Health List of Approved Providers for Antigen Rapid Testing for COVID-19 at Offsite Premises List updated as at 9 Jul 2021. S/N Contact Service Provider Site of Event Testing Address of Site Date of Event No. 1 OCBC Square 1 Stadium Place #01-K1/K2, Wave Mall, Singapore - 397628 57 Medical Clinic Visitor Centre of Singapore Sports Hub 8 Stadium Walk, Singapore 397699 - 66947078 (Geylang Bahru) Suntec Singapore Convention and Exhibition 1 Raffles Boulevard Singapore 039593 - Centre 2 57 Medical Clinic Holiday Inn Singapore Atrium 317 Outram Road, Singapore 169075 - 62353490 (Yishun) 3 Asiamedic Wellness Asiamedic Astique The Aesthetic Clinic Pte. Ltd. 350 Orchard Road #10-00 Shaw House Singapore - 67898888 Assessment Centre 238868 4 Acumen Diagnostics Former Siglap Secondary School 10 Pasir Ris Drive 10, Singapore 519385 - 69800080 Pte. Ltd. 5 9 Dec 2020 13 and 14 Jan 2021 24 and 25 Jan 2021 Sands Expo and Convention Centre 10 Bayfront Avenue, Singapore 018956 4 Feb 2021 24 and 25 Mar 2021 19 Apr 2021 PUB Office 40 Scotts Road, #22-01 Environment Building, Ally Health - 67173737 Singapore 228231 The Istana 35 Orchard Road, Singapore 238823 3 and 4 Feb 2021 11 Feb 2021 One Marina Boulevard 1 Marina Boulevard, Singapore 018989 11 Feb 2021 Rasa Sentosa Singapore 101 Siloso Road, Singapore 098970 Shangri-La Hotel Singapore 22 Orange Grove Road, Singapore 258350 22 Apr 2021 D'Marquee@Downtown East 1 Pasir Ris Close, Singapore 519599 - Intercontinental Hotel 80 Middle Road, Singapore 188966 - Page 1 of 133 Palfinger Asia Pacific Pte Ltd 4 Tuas Loop, Singapore 637342 - ST ENGINEERING MARINE LTD.