ETHJ Vol-25 No-1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Postwar Urban Redevelopment and North Dallas Freedman's Town

Roads to Destruction: Postwar Urban Redevelopment and North Dallas Freedman’s Town by Cynthia Lewis Like most American cities following World War II, Dallas entered a period of economic prosperity, and city leaders, like their counterparts throughout the nation, sought to maximize that prosperity through various urban renewal initiatives.1 Black urban communities across the country, branded as blighted areas, fell victim to the onslaught of postwar urban redevelopment as city leaders initiated massive renewal projects aimed at both bolstering the appeal and accessibility of the urban center and clearing out large sections of urban black neighborhoods. Between the years 1943 and 1983, Dallas city officials directed a series of massive redevelopment projects that decimated each of the city’s black communities, displacing thousands and leaving these communities in a state of disarray.2 This paper, which focuses on the historically black Dallas community of North Dallas, argues that residential segregation, which forced the growth and evolution of North Dallas, ultimately led to the development of slum conditions that made North Dallas a target for postwar slum clearance projects which only served to exacerbate blight within the community. Founded in 1869 by former slaves, North Dallas, formerly known as Freedman’s Town, is one of the oldest black neighborhoods in Dallas.3 Located just northeast of downtown and bounded by four cemeteries to the north and white-owned homes to the south, east, and west, the area became the largest and most densely populated black settlement in the city. Residential segregation played a pivotal role in the establishment and evolution of North Dallas, as it did with most black urban communities across the country.4 Racial segregation in Dallas, with its roots in antebellum, began to take 1 For an in-depth analysis of the United States’ postwar economy, see Postwar Urban America: Demography, Economics, and Social Policies by John F. -

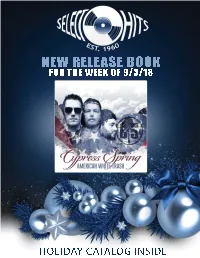

Sohnewreleasebook.Pdf

Cypress Spring American White Trash on Average Joes Entertainment $15.99 SRP street: 10.12.18 UPC: 661869003207 Holding true to the cliché ‘country to the core,’ Florida-based country rap group Cypress Spring’s beat-driven music and down-home Southern lifestyle continue to connect with fans far and wide. On their long-awaited 12- track album American White Trash, the country rap trio flies a proud flag espousing the virtues of hard work and partying harder, patriotism, God and family – virtues closely aligned with their exploding fan base. Cypress Spring’s music was first introduced on CMT’s highest rated hit show “Party Down South.” Since then, the band has gggarnered over 18 million YouTube views of their breakthrough video “Way of Life” with over 25 million streams across digital radio platforms, over 100,000 fans across social media and more than 500,000 sales on the popular Mud Digger compilation albums. Sonically, the 12-track album has something for every fan. Patriotism shines through on the driving, hit song and video “America,” while “Whiskey’s Always Strong,” a standout ballad, will surely tug at the heartstrings and “Needle Junkie,” a clever throwback, sings the praises of vinyl records. Recognized as the hottest newcomers on the country rap music scene, the band is quickly gaining fans and growing their fan base. An extensive tour booked by Nashville’s Buddy Lee Agency is planned to support the new album. In addition, the marketing campaign includes major media mailings, playlist procurement on digital streaming platforms, online reviews, features and interviews, weekly webisodes with band members, Facebook live sessions, social media engagement, digital marketing and contesting and giveaways. -

Plan Your Next Trip

CHARLES AND MARY ANN GOODNIGHT RANCH STATE HISTORIC SITE, GOODNIGHT PRESERVE THE FUTURE By visiting these historic sites, you are helping the Texas Historical Commission preserve the past. Please be mindful of fragile historic artifacts and respectful of historic structures. We want to ensure their preservation for the enjoyment of future generations. JOIN US Support the preservation of these special places. Consider making a donation to support ongoing preservation and education efforts at our sites at thcfriends.org. Many of our sites offer indoor and outdoor facility rentals for weddings, meetings, and special events. Contact the site for more information. SEE THE SITES From western forts and adobe structures to Victorian mansions and pivotal battlegrounds, the Texas Historical Commission’s state historic sites illustrate the breadth of Texas history. Plan Your Next Trip texashistoricsites.com 1 Acton HISTORIC15 Kreische BrSITESewery DIVISION22 National Museum of the Pacific War 2 Barrington Plantation Texas16 Landmark Historical Inn Commission23 Old Socorro Mission 3 Caddo Mounds P.O.17 BoxLevi 12276,Jordan Plantatio Austin,n TX 7871124 Palmito Ranch Battleground 4 Casa Navarro 18 Lipantitla512-463-7948n 25 Port Isabel Lighthouse 5 Confederate Reunion Grounds [email protected] Magon Home 26 Sabine Pass Battleground 6 Eisenhower Birthplace 20 Mission Dolores 27 Sam Bell Maxey House 7 Fannin Battleground 21 Monument HIll 28 Sam Rayburn House 8 Fanthorp Inn 29 San Felipe de Austin 9 Fort Grin 30 San Jacinto Battleground and -

The TEXAS ARCHITECT INDEX

Off1cial Publication of the TEXAS ARCHITECT The Texas Society of ArchitiiCU TSA IS the off•cu11 organization of the Texas VOLUME 22 / MAY, 1972 / NO. 5 Reg•on of the Amer1c:an lnst1tut10n of Archllecu James D Pfluger, AlA Ed1t0r Taber Ward Managmg Ed110r Banny L Can1zaro Associate Eduor V. Raymond Smith, Al A Associate Ed1tor THE TEXAS ARCH ITECT " published INDEX monthly by Texas Society of Architects, 904 Perry Brooks Buildtng, 121 East 8th Street, COVER AND PAGE 3 Austen, Texas 78701 Second class postage pa1d at Ausun, Texas Application to matl at Harwood K. Sm 1th and Partners second clan postage rates Is pend1ng ot Aunen, Texas. Copynghtcd 1972 by the TSA were commissioned to design a Subscription price, $3.00 per year, In junior college complex w1th odvuncc. initial enrollment of 2500 Edllonal contnbut1ons, correspondence. and students. The 245-acre site w1ll advertising material env1ted by the editor Due to the nature of th publlcauon. editorial ultimately handle 10,000 full-time conuulbullons cannot be purchoscd students. Pub11sher g•ves p rm1ss on for reproduction of all or part of edatonal matenal herem, and rcQulllts publication crcd1t be IJIVCn THE PAGE 6 TEXAS ARCHITECT, and Dllthor of matenol when lnd•C3ted PubiJcat•ons wh1ch normally The Big Thicket - a wilderness pay for editon I matenal are requested to grvc under assault. Texans must ac conStdcrat on to the author of reproduced byhned feature matenal cept the challenge of its surv1val. ADVERTISERS p 13 - Texas/Unicon Appearance of names and p1ctures of products and services m tither ed1torlal or PAGE 11 Structures. -

Chapter 10: the Alamo and Goliad

The Alamo and Goliad Why It Matters The Texans’ courageous defense of the Alamo cost Santa Anna high casualties and upset his plans. The Texas forces used the opportunity to enlist volunteers and gather supplies. The loss of friends and relatives at the Alamo and Goliad filled the Texans with determination. The Impact Today The site of the Alamo is now a shrine in honor of the defenders. People from all over the world visit the site to honor the memory of those who fought and died for the cause of Texan independence. The Alamo has become a symbol of courage in the face of overwhelming difficulties. 1836 ★ February 23, Santa Anna began siege of the Alamo ★ March 6, the Alamo fell ★ March 20, Fannin’s army surrendered to General Urrea ★ March 27, Texas troops executed at Goliad 1835 1836 1835 1836 • Halley’s Comet reappeared • Betsy Ross—at one time • Hans Christian Andersen published given credit by some first of 168 stories for making the first American flag—died 222 CHAPTER 10 The Alamo and Goliad Compare-Contrast Study Foldable Make this foldable to help you compare and contrast the Alamo and Goliad—two important turning points in Texas independence. Step 1 Fold a sheet of paper in half from side to side. Fold it so the left edge lays about 1 2 inch from the right edge. Step 2 Turn the paper and fold it into thirds. Step 3 Unfold and cut the top layer only along both folds. This will make three tabs. Step 4 Label as shown. -

Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl Philemon Isaiah Amos

ENGL 4384: Senior Seminar Student Anthology Fall 2012 Dr. Rebecca Harrison, Professor Department of English & Philosophy Printed on campus by UWG Publications and Printing. A Culture of Captivity: Subversive Femininity and Literary Landscapes Introduction 5 Dr. Rebecca L. Harrison I. Captive Women/Colonizing Texts “Heathenish, Indelicate and Indecent”: Male Authorship, 13 Narration, and the Transculturated, Mutable Female in James T. DeShields Cynthia Ann Parker, James Seaver’s A Narrative of the Life of Mrs. Mary Jemison, and Royal B. Stratton’s Captivity of the Oatman Girls Mary Catherine Lyons American Colonization and the Death of the Female 34 Captive Hannah Barnes Mitchell The Comfortable Captive: Applying Double-Voice 49 Discourse to Cotton Mather’s and John Greenleaf Whittier’s Depictions of Hannah Dustan’s Captivity to Ultimately Reveal Potential Female Agency Michelle Guinn II. Captive Others: Cutting through Sentimental Scripts “Lors, Chile! What’s You Crying ’Bout?”: Sympathy & Tears 62 in Harriet Jacobs’ Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl Philemon Isaiah Amos The Absolutely Real Ramifications of a Full-Time Genocide: 79 Exploring Mary Rowlandson’s Role in Alexie’s “Captivity” and True Diary Gina Riccobono III. Generic Adaptations & Dislodging the Narrative Tradition Transgressing the “bloody old hag”: Gender in Nathaniel 93 Hawthorne’s “The Duston Family” Michele Drane Creating the Autonomous Early American Woman: Angela 112 Carter and Caroline Gordon (Re) Employ the Female Captivity Narrative Genre Wayne Bell Death Becomes Her: The American Female Victim-Hero 125 Legacy Wes Shelton IV. Crossing the Borders of Captivity Capturing Dorinda Oakley 143 Dorinda Purser Unknowable and Thereby Unconquerable: Examining Ada 157 McGrath’s Resistance in The Piano Brett Hill ‘Bonds of Land and Blood’: Communal Captivity and 171 Subversive Femininity in Woodrell’s Winter’s Bone Jason Cole Contributors 190 A Culture of Captivity: Subversive Femininity and Literary Landscapes Dr. -

XXXI:4) Robert Montgomery, LADY in the LAKE (1947, 105 Min)

September 22, 2015 (XXXI:4) Robert Montgomery, LADY IN THE LAKE (1947, 105 min) (The version of this handout on the website has color images and hot urls.) Directed by Robert Montgomery Written by Steve Fisher (screenplay) based on the novel by Raymond Chandler Produced by George Haight Music by David Snell and Maurice Goldman (uncredited) Cinematography by Paul Vogel Film Editing by Gene Ruggiero Art Direction by E. Preston Ames and Cedric Gibbons Special Effects by A. Arnold Gillespie Robert Montgomery ... Phillip Marlowe Audrey Totter ... Adrienne Fromsett Lloyd Nolan ... Lt. DeGarmot Tom Tully ... Capt. Kane Leon Ames ... Derace Kingsby Jayne Meadows ... Mildred Havelend Pink Horse, 1947 Lady in the Lake, 1945 They Were Expendable, Dick Simmons ... Chris Lavery 1941 Here Comes Mr. Jordan, 1939 Fast and Loose, 1938 Three Morris Ankrum ... Eugene Grayson Loves Has Nancy, 1937 Ever Since Eve, 1937 Night Must Fall, Lila Leeds ... Receptionist 1936 Petticoat Fever, 1935 Biography of a Bachelor Girl, 1934 William Roberts ... Artist Riptide, 1933 Night Flight, 1932 Faithless, 1931 The Man in Kathleen Lockhart ... Mrs. Grayson Possession, 1931 Shipmates, 1930 War Nurse, 1930 Our Blushing Ellay Mort ... Chrystal Kingsby Brides, 1930 The Big House, 1929 Their Own Desire, 1929 Three Eddie Acuff ... Ed, the Coroner (uncredited) Live Ghosts, 1929 The Single Standard. Robert Montgomery (director, actor) (b. May 21, 1904 in Steve Fisher (writer, screenplay) (b. August 29, 1912 in Marine Fishkill Landing, New York—d. September 27, 1981, age 77, in City, Michigan—d. March 27, age 67, in Canoga Park, California) Washington Heights, New York) was nominated for two Academy wrote for 98 various stories for film and television including Awards, once in 1942 for Best Actor in a Leading Role for Here Fantasy Island (TV Series, 11 episodes from 1978 - 1981), 1978 Comes Mr. -

Texas Forts Trail Region

CatchCatch thethe PioPionneereer SpiritSpirit estern military posts composed of wood and While millions of buffalo still roamed the Great stone structures were grouped around an Plains in the 1870s, underpinning the Plains Indian open parade ground. Buildings typically way of life, the systematic slaughter of the animals had included separate officer and enlisted troop decimated the vast southern herd in Texas by the time housing, a hospital and morgue, a bakery and the first railroads arrived in the 1880s. Buffalo bones sutler’s store (provisions), horse stables and still littered the area and railroads proved a boon to storehouses. Troops used these remote outposts to the bone trade with eastern markets for use in the launch, and recuperate from, periodic patrols across production of buttons, meal and calcium phosphate. the immense Southern Plains. The Army had other motivations. It encouraged Settlements often sprang up near forts for safety the kill-off as a way to drive Plains Indians onto and Army contract work. Many were dangerous places reservations. Comanches, Kiowas and Kiowa Apaches with desperate characters. responded with raids on settlements, wagon trains and troop movements, sometimes kidnapping individuals and stealing horses and supplies. Soldiers stationed at frontier forts launched a relentless military campaign, the Red River War of 1874–75, which eventually forced Experience the region’s dramatic the state’s last free Native Americans onto reservations in present-day Oklahoma. past through historic sites, museums and courthouses — as well as historic downtowns offering unique shopping, dining and entertainment. ★★ ★★ ★★ ★★ ★★ ★★ ★★ 2 The westward push of settlements also relocated During World War II, the vast land proved perfect cattle drives bound for railheads in Kansas and beyond. -

Geological and Agricultural

SECOND ANNUAL REPORT OF THE GEOLOGICAL AND AGRICULTURAL SURVEY OF TEXAS, —BY— S. B. BUCKLEY, A. M., Ph. D., STATE GEOLOGIST. HOUSTON: a. c. gray, state printer. 1876. Second Annual Report of the State Geologist To His Excellency, Richard Coke, Governor of Texas: This second annual report of the geological and agricul- tural survey of the State, is respectfully submitted to your consideration. With many thanks for the aid you have given the work, I remain, yours truly, S. B. BUCKLEY, State Geologist. Introduction In the following pages I have given what I deem to be the most useful things pertaining to the agricultural and mineral resources of the State, which I have obtained during the past year, reserving much geological matter of scientific interestfor a final report. Since the last report, I have bought chemical apparatus sufficient to analyze mineral soils and mineral waters, which will be of great assistance in the future work of the survey. This appa- ratus has only been recently obtained. Austin, March 27th, 1876. 4 The Importance of Geology and Geological Surveys. I supposed that the importance of geology and geo- logical surveys was so well known and acknowleded that it would not be proper here to say anything about their usefulness. Nor should I allude to these things, had I not a few weeks ago, heard one who was called a leading member of the late Constitutional Convention, state in a public speech to that body, that "Geology is a humbug and he knew it to be so." It is strange that all the leading universities, colleges and schools of the civilized world have been teaching a humbug for the last 45 years; and still more strange, that all civilized countries, including every one of the United States, excepting Florida, have had or are having geolog- ical surveys made of their domains; also, the United States Government, during the last 15 years or more, has had and still continues to have geological surveys made of its territories. -

Big Thicket Reporter, Issue

BIG THICKET October-November-December 2013 Reporter Issue #120 BIG THICKET DAY, October 12 Big Thicket Day 2013 began with ences. She provided a litany of his a board and membership meeting achievements, including his 18-year with Jan Ruppel, President, presiding. summer workshops for Environ- mental Science Teachers, his publi- The keynote speaker was Dr. Ken cations, research, awards, and other Kramer, former Executive Direc- awards received and offi ces held. tor of the Lone Star Chapter, Sierra Club and current volunteer Water Mona Halvorsen reported on the Resources Chair and Legislative Thicket of Diversity, All Taxa Biodiversity Advisor, who addressed “Our State’s Inventory. (See Diversity Dispatch). Water Future – Progress and Chal- lenges.” Kramer noted that the Leg- Michael Hoke, Chair of the Neches islature made signifi cant eff orts this River Adventures Committee, pre- year to advance water conserva- sented a PowerPoint that included tion and to fi nance infrastructure, plans for curricula-based student use. and he outlined challenges ahead. Dr. Ken Kramer was the keynote Dr. James Westgate gave the elec- speaker for Big Thicket Day Ann Roberts, Chair of the Awards tion report for the Nominating Committee, presented the R.E. Committee. All nominees were After lunch, committees met to work Jackson Conservation Award to Dr. elected including Betty Grimes as on upcoming plans and projects. James Westgate, Lamar University Secretary plus two new directors — Professor of Earth and Space Sci- Leslie Dubey and Iolinda Gonzalez. Presidential Footnotes … By Jan Ruppel Because of the government shut- have a number of activities devel- the preservation and protection of down we held BTA’s 49th Big Thicket oping to celebrate throughout the the Big Thicket region and continue Day at First Baptist Church in Sara- year. -

Journals 2015.Pdf

『国際言語文化』創刊号巻頭言 京都外国語大学国際言語文化学会 会長 京都外国語大学・京都外国語短期大学 学長 松田 武 2013 年早春,学校法人京都外国語大学における研究活動の中核をなす組織として,「京 都外国語大学国際言語文化学会」が設立されました。会員の皆様,関係の皆様には学会設 立に際しましてさまざまな方面からご支援・ご協力賜りましたことにあらためて厚くお礼 申し上げます。 設立から約二年が経過しましたが,この学会の設立はたいへん意義深いものだったと実 感しております。広く学術・教育・社会の発展に貢献するのはもちろんのことですが,未 来社会を担う大学院生をはじめとした若手研究者の育成もさまざまな活動を通して活発に なってまいりました。また,京都外国語大学内の各種研究会を本学会の研究活動の中に組 み入れることで,刺激し合い,触発し合うといった一層の相乗効果も生まれています。研 究活動は基本的には孤独であり,常に自分との闘いではありますが,学会活動を通して新 しい出会いや発見が生まれ,異分野に触れることによって互いの多様性を認め合い,さら に研究の幅が広がるものと期待しています。 本誌は,この学会の会員,京都外国語大学・京都外国語短期大学に勤務するすべての教 職員,本学園の学生や本学を卒業したすべての若手研究者が研鑽し,研究成果を公表する 機会を提供することを目的としています。本誌の刊行をもって会員の研究活動を共有でき, 会員の研究成果の一部を今後のさらなる発展につなげられることを大変嬉しく思います。 最後になりましたが,本学会,および,本誌には「国際言語文化」が含まれています。 これは,京都外国語大学の建学の精神が「言語を通して世界の平和を」であることと関連 があります。この建学の精神を実現すべく,グローバルな視点からみた言語と文化に関す る優れた論考が本誌から多数発信され,各研究・教育分野での学術的な議論を誘発するき っかけとなればと願っております。 国際言語文化 創刊号 目次 研究論文 アラモ砦事件再考・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・牛島 万 ・・・1 カンタン・メイヤスーの思弁的唯物論・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・影浦 亮平 ・・・19 クリステーロの乱の展開と軍事社会史における士気の問題・・・・・・・古畑 正富 ・・・31 ブラジルにおける民主主義と政治指導者のカリスマ性・・・・・・・・・住田 育法 ・・・43 研究ノート 視覚障害をもつ留学生受け入れの課題 -京都外国語大学における授業外支援の取り組み-・・・・・・・・・・北川 幸子 ・・・57 辻野 美穂子 古澤 純 ラボラトリー方式の体験学習を取り入れた日本語クラスの試み・・・・・・・小松 麻美・・・67 第二言語習得の認知プロセスからみた協働学習の効果 -平和を題材にした日本語授業での協働学習の実践―・・・・・・・・中西 久実子 ・・・81 国際言語文化創刊号(2015 年 3 月) International Language and Culture First issue アラモ砦事件再考 牛島万 Contents Articles A Critical Study of the Fall of the Alamo・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・Takashi USHIJIMA 要旨 En este artículo, se trata del período desde la inmigración de los anglosajones a Texas hasta la Speculative materialism of Quentin Meillassoux・・・・・・・・・・・・・Ryohei -

The Dallas Social History Project

East Texas Historical Journal Volume 16 Issue 2 Article 10 10-1978 The "New" Social History and the Southwest: the Dallas Social History Project Henry D. Graff Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.sfasu.edu/ethj Part of the United States History Commons Tell us how this article helped you. Recommended Citation Graff, Henry D. (1978) "The "New" Social History and the Southwest: the Dallas Social History Project," East Texas Historical Journal: Vol. 16 : Iss. 2 , Article 10. Available at: https://scholarworks.sfasu.edu/ethj/vol16/iss2/10 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the History at SFA ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in East Texas Historical Journal by an authorized editor of SFA ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 52 EAST TEXAS HISTORICAL ASSOCIATION THE "NEW" SOCIAL HISTORY AND THE SOUTHWEST: THE DALLAS SOCIAL HISTORY PROJECT by Harvey D. Graff It does not take long for a newcomer to Southwestern history to discover that this region, with all its glorious legends and dramatic events, truly lacks a systematically recorded past. The Southwest abounds with the fruits of a long tradition of solid historiography and lodes of literateurs' lore. However, when the researcher looks below the level of colorful portrayals of personalities and battles and the saga offrontier settlement, he or she finds the basic ingredients of history as yet untouched. This is principally the case in social and economic history-and especially that of the modern style. The bare bones of social development, population profiles, and social differentiation and their interaction with a developing economy have simply not received the dry but grounded attention of the historian or social scientist.