80 Meditation Methods in Thailand: a Map of the Field

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

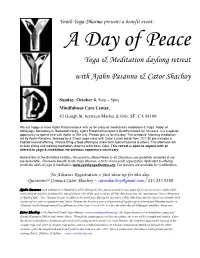

Yoga & Meditation Daylong Retreat with Ajahn Pasanno & Cator Shachoy

Youth Yoga Dharma presents a benefit event: A Day of Peace Yoga & Meditation daylong retreat with Ajahn Pasanno & Cator Shachoy Sunday, October 4, 9am – 5pm Mindfulness Care Center, 42 Gough St, between Market & Otis, SF, CA 94109 We are happy to have Ajahn Pasanno back with us for a day of mindfulness meditation & Yoga. Abbot of Abhayagiri Monastery in Redwood Valley, Ajahn Pasanno has been a Buddhist monk for 40 years. It is a special opportunity to spend time with Ajahn in The City. Please join us for this day! The schedule: Morning meditation led by Ajahn Pasanno, followed by a 2-hour yoga class with Cator. Lunch break from 12-1:30 pm includes a traditional meal offering. Please bring a food offering to share with Ajahn Pasanno & others. The afternoon will include sitting and walking meditation, dharma reflections, Q&A. This retreat is open to anyone with an interest in yoga & meditation. No previous experience necessary. Retreat fee: In the Buddhist tradition, this event is offered freely to all. Donations are gratefully accepted & are tax-deductible. Proceeds benefit Youth Yoga Dharma, a 501c-3 non-profit organization dedicated to offering youth the skills of yoga & meditation: www.youthyogadharma.org. Tax receipts are available for contributions. No Advance Registration – Just show up for this day. Questions?? Contact Cator Shachoy – [email protected] / 415.235.9380 Ajahn Pasanno took ordination in Thailand in 1974. During his first year as a monk he was taken by his teacher to meet Ajahn Chah, with whom he asked to be allowed to stay and train. -

Buddhist Revivalist Movements Comparing Zen Buddhism and the Thai Forest Movement Buddhist Revivalist Movements Alan Robert Lopez Buddhist Revivalist Movements

Alan Robert Lopez Buddhist Revivalist Movements Comparing Zen Buddhism and the Thai Forest Movement Buddhist Revivalist Movements Alan Robert Lopez Buddhist Revivalist Movements Comparing Zen Buddhism and the Thai Forest Movement Alan Robert Lopez Chiang Mai , Thailand ISBN 978-1-137-54349-3 ISBN 978-1-137-54086-7 (eBook) DOI 10.1057/978-1-137-54086-7 Library of Congress Control Number: 2016956808 © The Editor(s) (if applicable) and The Author(s) 2016 This work is subject to copyright. All rights are solely and exclusively licensed by the Publisher, whether the whole or part of the material is concerned, specifi cally the rights of translation, reprinting, reuse of illustrations, recitation, broadcasting, reproduction on microfi lms or in any other physical way, and transmission or information storage and retrieval, electronic adaptation, computer software, or by similar or dissimilar methodology now known or hereafter developed. The use of general descriptive names, registered names, trademarks, service marks, etc. in this publication does not imply, even in the absence of a specifi c statement, that such names are exempt from the relevant protective laws and regulations and therefore free for general use. The publisher, the authors and the editors are safe to assume that the advice and information in this book are believed to be true and accurate at the date of publication. Neither the publisher nor the authors or the editors give a warranty, express or implied, with respect to the material contained herein or for any errors or omissions that may have been made. Cover image © Nickolay Khoroshkov / Alamy Stock Photo Printed on acid-free paper This Palgrave Macmillan imprint is published by Springer Nature The registered company is Nature America Inc. -

The Bhikkhunī-Ordination Controversy in Thailand

JIABS Journal of the International Association of Buddhist Studies Volume 29 Number 1 2006 (2008) The Journal of the International Association of Buddhist Studies (ISSN 0193-600XX) is the organ of the International Association of Buddhist Studies, Inc. It welcomes scholarly contributions pertaining to all facets of Buddhist Studies. EDITORIAL BOARD JIABS is published twice yearly, in the summer and winter. KELLNER Birgit Manuscripts should preferably be sub- KRASSER Helmut mitted as e-mail attachments to: Joint Editors [email protected] as one single file, complete with footnotes and references, BUSWELL Robert in two different formats: in PDF-format, and in Rich-Text-Format (RTF) or Open- CHEN Jinhua Document-Format (created e.g. by Open COLLINS Steven Office). COX Collet GÓMEZ Luis O. Address books for review to: HARRISON Paul JIABS Editors, Institut für Kultur - und Geistesgeschichte Asiens, Prinz-Eugen- VON HINÜBER Oskar Strasse 8-10, AT-1040 Wien, AUSTRIA JACKSON Roger JAINI Padmanabh S. Address subscription orders and dues, KATSURA Shōryū changes of address, and UO business correspondence K Li-ying (including advertising orders) to: LOPEZ, Jr. Donald S. Dr Jérôme Ducor, IABS Treasurer MACDONALD Alexander Dept of Oriental Languages and Cultures SCHERRER-SCHAUB Cristina Anthropole SEYFORT RUEGG David University of Lausanne CH-1015 Lausanne, Switzerland SHARF Robert email: [email protected] STEINKELLNER Ernst Web: www.iabsinfo.net TILLEMANS Tom Fax: +41 21 692 30 45 ZÜRCHER Erik Subscriptions to JIABS are USD 40 per year for individuals and USD 70 per year for libraries and other institutions. For informations on membership in IABS, see back cover. -

The Way It Is

The way it is By Ajahn Sumedho 1 Ajahn Sumedho 2 Venerable Ajahn Sumedho is a bhikkhu of the Theravada school of Buddhism, a tradition that prevails in Sri Lanka and S.E. Asia. In this last century, its clear and practical teachings have been well received in the West as a source of understanding and peace that stands up to the rigorous test of our current age. Ajahn Sumedho is himself a Westerner having been born in Seattle, Washington, USA in 1934. He left the States in 1964 and took bhikkhu ordination in Nong Khai, N.E. Thailand in 1967. Soon after this he went to stay with Venerable Ajahn Chah, a Thai meditation master who lived in a forest monastery known as Wat Nong Pah Pong in Ubon Province. Ajahn Chah’s monasteries were renowned for their austerity and emphasis on a simple direct approach to Dhamma practice, and Ajahn Sumedho eventually stayed for ten years in this environment before being invited to take up residence in London by the English Sangha Trust with three other of Ajahn Chah’s Western disciples. The aim of the English Sangha Trust was to establish the proper conditions for the training of bhikkhus in the West. Their London base, the Hampstead Buddhist Vihara, provided a reasonable starting point but the advantages of a more gentle rural environment inclined the Sangha to establishing a forest monastery in Britain. This aim was achieved in 1979, with the acquisition of a ruined house in West Sussex subsequently known as Chithurst Buddhist Monastery or Cittaviveka. -

Amaravati Calendar 08

2008 2551 PHOTO AND TEXT CREDITS This 2008 calendar features pictures by a variety of photographers. © Wat Pah Nanachat (Feb, Mar, May, Aug, Oct, Dec); © Amaravati Publications (Apr); © Aruna Publications (Jan, June, Sept); © Khun Tu (July, Nov). Scriptural quotes on each page are English renderings of texts from the Pali Canon. The translations draw on the works from: “A Dhammapada for Contemplation” © Aruna Publications 2006; and texts from Itivuttaka 3.50; Theragatha 1.3 from Thanissaro Bhikkhu © Access to Insight 2005 edition, www.accesstoinsight.org For free distribution. This work may be republished, reformatted, reprinted, and redistributed in any medium. It is the author's wish, however, that any such republication and redistribution be made available to the public on a free and unrestricted basis and that translations and other derivative works be clearly marked as such. Appreciation is expressed to all who have offered assistance with this production. LUNAR OBSERVANCE DAYS These days are devoted to quiet reflection at the monastery. Visitors may come and take the Precepts for the day and join in all or part of the extended evening meditation. The dates for the lunar calendar are determined by traditional methods of calculation, and are not always the same as the precise astronomical occurrences. THE MAJOR FULL-MOON DAYS OF 2008 – 2551/52 Magha Puja March 21 (‘Sangha Day’) Commemorates the spontaneous gathering of 1,250 arahants, to whom the Buddha gave the exhortation on the basis of the discipline (Ovada Patimokkha). Vesakha Puja (Wesak) May 19 (‘Buddha Day’) Commemorates the birth, enlightenment and passing away of the Buddha. -

Small Boat, Great Mountain

small boat, great mountain AMARO BHIKKHU Theravadanµ Reflections on The Natural Great Perfection May whatever goodness that arises from reading these pages be dedicated to the welfare of Patricia Horner, my greatly beloved mother. In kindness and unselfishness unsurpassed, she showed me the beauty of the world in her endlessly caring and generous heart. Small Boat, Great Mountain small boat, great mountain Therava-dan Reflections on the Natural Great Perfection AMARO BHIKKHU ABHAYAGIRI MONASTERY Abhayagiri Buddhist Monastery 16201 Tomki Road Redwood Valley, CA 95470 www.abhayagiri.org 707-485-1630 © 2003 Abhayagiri Monastic Foundation Copyright is reserved only when reprinting for sale. Permission to reprint for free distribution is hereby given as long as no changes are made to the original. Printed in the United States of America First edition 12345/ 07 06 05 04 03 This book has been sponsored for free distribution. Front cover painting by Ajahn Jitindriyaµ Brush drawings by Ajahn Amaro Cover and text design by Margery Cantor isbn 0-9620640-6-8 Namo tassa bhagavato arahato sammasambuddhassaµ Namo tassa bhagavato arahato sammasambuddhassaµ Namo tassa bhagavato arahato sammasambuddhassaµ Contents Foreword by Ven. Tsoknyi Rinpoche ix Preface by Guy Armstrong xi Acknowledgements xvii Abbreviations xix essence of mind one Ultimate and Conventional Reality 3 two The Place of Nonabiding 15 being buddha three The View from the Forest 35 four Cessation of Consciousness 55 five Immanent and Transcendent 73 who are you? six No Buddha Elsewhere 97 seven Off the Wheel 121 eight The Portable Retreat 147 Selected Chants 159 Glossary 171 Index 179 Foreword A jahn amaro is a true follower of the Buddha and holder of the teaching lineage of the Theravaµda tradition. -

Forest Sangha Calendar

Forest Sangha Calendar 2013 - 2556 This 2013 calendar features photographs from a variety of contributors. We are grateful for their generosity and skill. We would like to acknowledge the support of many people in the preparation of this calendar, especially to the Kataññnutā group of Malaysia, Singapore and Australia, for bringing it into production. Monthly Dhamma quotes are adapted from translated teachings given by Venerable Ajahn Chah. For further teachings, see www.fsbooks.org/ajahn-chah-teachings LUNAR OBSERVANCE DAYS These days are devoted to quiet reflection at the monastery. G# # VisitorsH# may come and take the Precepts for the day and join in all or part of the extended evening meditation. The dates for the lunar calendar are determined by traditional methods of calculation, and are not always the same as the precise astronomical occurrences. THE MAJOR FULL-MOON DAYS FOR 2013-2556 Māgha Pūjā: February 25 (‘Sangha Day’) Commemorates the spontaneous gathering of 1250 arahants to whom the Buddha gave an exhortation on the basis of the Discipline (Ovāda Pāṭimokkha). Vesākha Pūjā: May 24 (‘Buddha Day’) Commemorates the birth, enlightenment and passing away of the Buddha. Āsāḷhā Pūjā: July 22 (‘Dhamma Day’) Commemorates the Buddha’s first discourse, given to the five samaṇas in the Deer Park at Sarnath, near Varanasi. The traditional Rainy-Season Retreat (Vassa) begins on the next day. Pavāraṇā Day: October 19 This marks the end of the three-month Vassa retreat. During the following month, lay people may offer the Kaṭhina robe as part of a general alms-giving ceremony. www.forestsangha.org www.forestsanghapublications.org Calendar production by Aruna Publications, Aruna Ratanagiri Buddhist Monastery, www.ratanagiri.org.uk © Aruna Publications 2012 ‘‘There is no end to what can be said about meditation. -

The Propagation of Theravada Buddhism in Foreign Countries: the Case of the Dhammakaya Temple in Thailand

The propagation of Theravada Buddhism in foreign countries: The Case of the Dhammakaya Temple in Thailand Komazawa University Hidetake YANO This paper examines the organization, management, and propagation of the Wat Phra Dhammakaya (Dhammakaya Temple) in foreign countries, which is a newly arisen Buddhist group in Thailand. This group started its activity in 1970, and in 1977 it was recognized by the Thai government as a formal Buddhist temple belonging to the Sangha of Thai Theravada Buddhism. For this reason, it is difficult to term the Wat Phra Dhammakaya as a New Religious Movement. However, this temple has unique meditation practices, and its doctrines regarding Nirvana are different from mainstream Theravada Buddhism, hence, it is categorized as a new type of Buddhism in the Thai Buddhist Sangha. In orthodox forms of meditation in Theravada Buddhism, one starts with concentration on one’s own breathing or on one’s senses and emotions, then moves to the monitoring of and detachment from of the senses and emotions. However in the Dhammakaya style of meditation, one starts from meditating on a light (sphere) crystal ball or on a Buddha image in their mind, then cultivates the inner self along various stages that eventually lead to Dhammakaya, the Dharma body. This meditation aims to achieve “Nirvana” as the “true self” through the experience of unity with the Dhammakaya in the mind. Furthermore, it is believed that Dhammakaya meditation produces supernatural powers of protection and worldly happiness. Most of the members of this temple belong to the new urban middle class, who have a higher educational level, it has also spread to urbanites with less education and to the local people. -

The Liberating Teachings Buddhadasa

THE LIBERATING TEACHINGS OF BUDDHADASA ON As recorded by Santidhammo Bhikkhu aka Jack Kornfield THE LIBERATING TEACHINGS OF BUDDHADĀSA ON SUCHNESS As recorded by Santidhammo Bhikkhu aka Jack Kornfield This electronic edition is the fruit of the collaboration of a network of volunteers and has been made possible with the kind permission of Ajahn Jack Kornfield. © Buddhadasa Indapanno Archives, 2017 Published by The Buddhadāsa Indapañño Archives Vachirabenjatas Park (Rot Fai Park) Nikom Rot Fai Sai 2 Rd., Chatuchak, Bangkok, 10900 Thailand. Tel. +66 2936 2800 Fax. +66 2936 2900 www.bia.or.th For free distribution only Anumodanā To all Dhamma Comrades, those helping to spread Dhamma: Break out the funds to spread Dhamma to let Faithful Trust flow, Broadcast majestic Dhamma to radiate long-living joy. Release unexcelled Dhamma to tap the spring of Virtue, Let safely peaceful delight flow like a cool mountain stream. Dhamma leaves of many years sprouting anew, reaching out, To unfold and bloom in the Dhamma Centers of all towns. To spread lustrous Dhamma and in hearts glorified plant it, Before long, weeds of sorrow, pain, and affliction will flee. As Virtue revives and resounds throughout Thai society, All hearts feel certain love toward those born, aging, and dying. Congratulations and Blessings to all Dhamma Comrades, You who share Dhamma to widen the people’s prosperous joy. Heartiest appreciation from Buddhadāsa Indapañño, Buddhist Science ever shines beams of Bodhi long-lasting. In grateful service, fruits of merit and wholesome successes, Are all devoted in honor to Lord Father Buddha. Thus may the Thai people be renowned for their Virtue, May perfect success through Buddhist Science awaken their hearts. -

Buddhadasa's Movement: an Analysis of Its Origins, Development, and Social Inpact

Buddhadasa's Movement: An Analysis of Its Origins, Development, and Social Inpact Dissertation zur Erlangung des Grades eines Doktors der Sozialwissenschaften vorgelegt im WS 1991/1992 an der Fakultät für Soziologie Universität Bielefeld Verfasserin: Suchira Payulpitack Jakob-Kaiserstr. 16a/315 4800 Bielefeld 1 Gutachter: Prof. Dr. Hans-Dieter Evers Bielefeld, im Oktober 1991 Contents List of Tables, Figures, and Maps i Notes and Translation ii Acknowledgements iii Pages Chapter 1 Introduction Studying Buddhadasa's Movement ...................................................................... 3 Studies in the Sociology of Religious Movements................................................ 7 Data Collection, Organization, and Aims of the Study ........................................17 Chapter 2 Social Change and Religious Movements in Thailand Mongkut and His Religious Reforms in the Nineteenth Century..........................21 Socio-Political Change and Religious Development -- 1886-1932 .......................................................................................................26 Constitutional Era (1932-)..................................................................................41 Religious Movements in Contemporary Thailand................................................56 Chapter 3 Life History of Buddhadasa Bhikkhu Family, Childhood, and Education......................................................................72 Early Life as Buddhist Monk..............................................................................82 -

Thesis for Submission

FROM LAṄKĀ TO LĀN NĀ: REGIONAL BHIKKHUNĪ IDENTITY AND TRANSNATIONAL BUDDHIST NETWORKS A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Cornell University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Asian Studies by Claire Poggi Elliot August 2020 © 2020 Claire Poggi Elliot ABSTRACT In 1996 the first public ordination of Theravāda bhikkhunī took place in India, spurring the creation of the first new lineage of female Theravāda monastics in a millennium. Despite debates about their legitimacy, this new lineage spread quickly within Sri Lanka, and then to Thailand in 2001. Because ordaining women remains illegal in Thailand, new bhikkhunī fly to Sri Lanka for their upasampadā ritual, resulting in a strong and continuing international network. This does not mean, however, that the bhikkhunī movement is a homogeneous or entirely harmonious one. Using data gathered from ethnographic fieldwork, interviews, and publications by bhikkhunī in Sri Lanka and Thailand, I look specifically at how one of the largest Thai bhikkhunī communities, Nirotharam, centered in Chiang Mai, navigates their local and trans-local contexts. These bhikkhunī localize their practice in northern-Thai forms of Buddhist monasticism. This gains Nirotharam support from local northern monks, who use their patronage of the bhikkhunī as a form of criticism against the central Thai Sangha, though the women themselves vocally support the central Thai Sangha. This careful mediation between local and national support is further complicated by the Thai bhikkhunī's dependence on Sri Lankan monastics for ordinations. Nirotharam bhikkhunī are in constant communication with, and under surveillance by, Sri Lankan monastics thanks to modern technological developments. -

The Efficacies of Trance-Possession Ritual Performances In

The efficacies of trance-possession ritual performances in contemporary Thai Theravada Buddhism Submitted by Paveena Chamchoy to the University of Exeter as a thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Drama In January 2013 This thesis is available for Library use on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement. I certify that all material in this thesis which is not my own work has been identified and that no material has previously been submitted and approved for the award of a degree by this or any other University. Signature: ………………………………………………………………………. Abstract This thesis is a study of the contemporary forms of trance-possession rituals performed in Thai Buddhism. It explores the way in which the trance-possession rituals are conceptualised by Thai Buddhist people as having therapeutic potentiality, through the examination of the ritual efficacy that is established through participants’ lived experience. My main research question focuses on how trance-possession rituals operate within a contemporary Thai cultural context and what are the contributory factors to participants’ expressing a sense of efficacy in the ritual. This thesis proposes that applied drama can be used as a ‘lens’ to examine the participants’ embodied experiences, particularly in relation to the ritual’s potential efficacy. In addition, the thesis also draws on discourses from anthropology, to enable a clearer understanding of the Thai socio-cultural aspects. I proceed to examine the efficacy of trance-possession ritual by focusing on the Parn Yak chanting ritual and rituals in sak yant, the spiritual tattoo tradition, as the two examples.