Validity and Reliability of a Revised Scale of Attitude Towards Buddhism (TSAB-R)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Buddhist Discussion Centre (Upwey) Ltd. 33 Brooking St

Buddhist Discussion Centre (Upwey) Ltd. 33 Brooking St. Upwey 3158 Victoria Australia. Telephone 754 3334. (Incorporated in Victoria) NEWSLETTER N0. 11 MARCH 1983 REGISTERED BY AUSTRALIA POST PUBLICATION NO. VAR 3103 ISSN 0818-8254 Inauguration of 1000th Birth Anniversary of Atisa Dipankar Srijnan - Dhaka, Bangladesh,1983. Chief Martial Law Administrator, (C.M.L.A.) Lt. Gen. H. M. Ershad inaugurated the Week-long programme commencing on 26th February, 1983. A full report of this event appeared in the Bangladesh Observer, 20th February, 1983, at Page 1, under the heading "All Religions enjoy equal rights". The C.M.L.A. said it was a matter of great pride that Atisa Dipankar Srijnan had established Bangladesh in the comity of nations an honourable position by his unique contributions in the field of knowledge. Therefore, Dipankar is not only the asset and pride of the Buddhist community; rather he is the pride of Bangladesh and an asset for the whole nation. The C.M.L.A. hoped that the people being imbibed with the ideals of sacrifice, patriotism, friendship and love of mankind of Atisa Dipankar would take part in the greater struggle of building the nation. He called upon the participating delegates to carry with them the message of peace, fraternity, brotherhood, love and non-violence from the people of Bangladesh to the people of their respective countries. Besides Bangladesh, about 50 delegates from about 20 countries took part in the celebration. John D. Hughes, Director of B.D.C. (Upwey), representing Australia at the Conference, would like to express his sincere gratitude to the C.M.L.A. -

Colonialism, Education and Rural Buddhist Communities in Bangladesh Bijoy Barua University of Toronto, Canada, [email protected]

International Education Volume 37 Issue 1 Fall 2007 Colonialism, Education and Rural Buddhist Communities in Bangladesh Bijoy Barua University of Toronto, Canada, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://trace.tennessee.edu/internationaleducation Copyright © 2007 by the University of Tennessee. Reproduced with publisher's permission. Further reproduction of this article in violation of the copyright is prohibited. http://trace.tennessee.edu/internationaleducation/vol37/iss1/4 Recommended Citation Barua, Bijoy (2007). Colonialism, Education and Rural Buddhist Communities in Bangladesh. International Education, Vol. 37 Issue (1). Retrieved from: http://trace.tennessee.edu/internationaleducation/vol37/iss1/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Trace: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in International Education by an authorized administrator of Trace: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Barua COLONIALISM, EDUCATION, AND RURAL BUDDHIST COMMUNITIES IN BANGLADESH Bijoy Barua Ontario Institute for Studies in Education University of Toronto Toronto, Canada Cultural homogenization through the establishment of a central- ized and standardized curriculum in education has become the dominant model in Bangladesh today, a model of education that is deeply rooted in the colonial legacy of materialism, acquisitiveness, and social exclusion (B. Barua, 2004; Gustavsson, 1990). Such a model is predicated on the notion that Bangladesh “is culturally homogenous, with one language, one domi- nant religion, and no ethnic conflict” (Hussain, 2000, p. 52). Predictably and unfortunately, the prospects for decolonization in a “post-colonial/in- dependence context” still appear to be bleak since the state continues to rely on a centrally controlled and standardized educational system that is committed to cultural homogenization and social exclusion—a process that is being encouraged by foreign aid and international assistance (B. -

Number 3 2011 Korean Buddhist Art

NUMBER 3 2011 KOREAN BUDDHIST ART KOREAN ART SOCIETY JOURNAL NUMBER 3 2011 Korean Buddhist Art Publisher and Editor: Robert Turley, President of the Korean Art Society and Korean Art and Antiques CONTENTS About the Authors…………………………………………..………………...…..……...3-6 Publisher’s Greeting…...…………………………….…….………………..……....….....7 The Museum of Korean Buddhist Art by Robert Turley…………………..…..…..8-10 Twenty Selections from the Museum of Korean Buddhist Art by Dae Sung Kwon, Do Kyun Kwon, and Hyung Don Kwon………………….….11-37 Korean Buddhism in the Far East by Henrik Sorensen……………………..…….38-53 Korean Buddhism in East Asian Context by Robert Buswell……………………54-61 Buddhist Art in Korea by Youngsook Pak…………………………………..……...62-66 Image, Iconography and Belief in Early Korean Buddhism by Jonathan Best.67-87 Early Korean Buddhist Sculpture by Lena Kim…………………………………....88-94 The Taenghwa Tradition in Korean Buddhism by Henrik Sorensen…………..95-115 The Sound of Ecstasy and Nectar of Enlightenment by Lauren Deutsch…..116-122 The Korean Buddhist Rite of the Dead: Yeongsan-jae by Theresa Ki-ja Kim123-143 Dado: The Korean Way of Tea by Lauren Deutsch……………………………...144-149 Korean Art Society Events…………………………………………………………..150-154 Korean Art Society Press……………………………………………………………155-162 Bibliography of Korean Buddhism by Kenneth R. Robinson…...…………….163-199 Join the Korean Art Society……………...………….…….……………………...……...200 About the Authors 1 About the Authors All text and photographs contained herein are the property of the individual authors and any duplication without permission of the authors is a violation of applicable laws. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED BY THE INDIVIDUAL AUTHORS. Please click on the links in the bios below to order each author’s publications or to learn more about their activities. -

The Global Connections of Gandhāran Art

More Gandhāra than Mathurā: substantial and persistent Gandhāran influences provincialized in the Buddhist material culture of Gujarat and beyond, c. AD 400-550 Ken Ishikawa The Global Connections of Gandhāran Art Proceedings of the Third International Workshop of the Gandhāra Connections Project, University of Oxford, 18th-19th March, 2019 Edited by Wannaporn Rienjang Peter Stewart Archaeopress Archaeology Archaeopress Publishing Ltd Summertown Pavilion 18-24 Middle Way Summertown Oxford OX2 7LG www.archaeopress.com ISBN 978-1-78969-695-0 ISBN 978-1-78969-696-7 (e-Pdf) DOI: 10.32028/9781789696950 www.doi.org/10.32028/9781789696950 © Archaeopress and the individual authors 2020 Gandhāran ‘Atlas’ figure in schist; c. second century AD. Los Angeles County Museum of Art, inv. M.71.73.136 (Photo: LACMA Public Domain image.) This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. This book is available direct from Archaeopress or from our website www.archaeopress.com Contents Acknowledgements ����������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������iii Illustrations ����������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������iii Contributors ��������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� iv Preface ������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������ -

Buddhist Echoes in University Education: a Comparative Study of China and Canada1

362 Part 4: Higher Education, Lifelong Learning and Social Inclusion DONG ZHAO BUDDHIST ECHOES IN UNIVERSITY EDUCATION: A COMPARATIVE STUDY OF CHINA AND CANADA1 Abstract Postmodern university education should provide students with, among other things, a third eye of wisdom to see the world and themselves. The enculturation of Buddhism in university education serves to realize this grand aim. This paper first examines the historical development and practical significance of the Buddhist components in both Chinese and Canadian contexts. Based on the cases of representative universities in the two countries, it then analyzes the permeation of Buddhism in the two countries’ university education, comparing the implications of Buddhist education in their respective higher-learning contexts. The findings indicate how, in their own ways, Chinese and Canadian universities employ Buddhist concepts in shaping students’ morality, enriching the humanistic and / or liberal education and assisting students in adapting to the changing world. Buddhism and Society in Postmodern Contexts: The Case of China Buddhism in China is more than 2,000 years old. Its greatest popularity and climactic development was in the Tang Dynasty (AD 618-907). As New China walked on the road of socialism, religion was undergoing a revival. As life gets more materialistically oriented, and urban pressures increase, spiritual needs are becoming more of a necessity than other modern conveniences. Buddhism is showing signs of vigorous life in the cities and countryside of China as a result of its vitality to adjust itself to modern conditions. This strong resurgence of Buddhism in contemporary China, such as the renovation of monasteries, the various Buddhist ceremonies and cultural festivals may be explained by the softening or flexibility of the Communist Party’s policy towards religions after the Reform and Open policies in the early 80s of the 20th century.2 Buddhism helps the present-day Chinese to find meaning and value in a rapidly changing society. -

1 the Lotus in the West Hannah Olle Buddhism in Britain Is a Relatively

The Lotus in the West Hannah Olle Buddhism in Britain is a relatively new phenomenon. Tentatively, however, the lotus is growing and taking root. The Sheffield Buddhist Centre is a small element of this. The Centre is a part of the Friends of the Western Buddhist Order (FWBO), a worldwide organisation which was set up in Britain in 1967, by a British monk named Sangararkshita, who had been ordained in India after the Second World War. His aim was to ‘translate’ Buddhism so that it would be accessible for Westerners. Today, the movement has a Centre in most major cities in Britain, although membership numbers still remain relatively low. Each Centre organises classes for the practice of meditation and rituals, as well as the study of Buddhist texts. There are three levels of participation: ‘Friends of the Order’, whose only involvement is practicing at the Centre; ‘Mitras’, who have made a small commitment to the Order; and those who have joined the Order. This paper is an account of a small-scale study of the Sheffield Centre. In order to establish a context for this study, I shall begin by considering theories of religion 1 and modernity in the West, ideas concerning New Religious Movements and the New Age, and the literature about Buddhism in Britain. Modernity, disenchantment and secularisation in the rational world Approaches to religion in the modern Western world fall into three strands: those which view religion in decline as a result of modernity; those which acknowledge a change in the nature of religion in society, but argue that spirituality still exists in some form; and, more recently, those which consider religion from a postmodern perspective. -

1 Bangladesh

Bangladesh – Researched and compiled by the Refugee Documentation Centre of Ireland on 30 January 2015 General information on Buddhism in Bangladesh, how to be initiated, practice, schools, monks. Can somebody, in Bangladesh, become a monk without any theological training? Do Buddhist monk in Bangladesh necessarily belong to either the Theravada school or the Mahayana school? The most recent US Department of State report on religious freedom in Bangladesh, in “Section I. Religious Demography”, states: “The U.S. government estimates the total population at 163.7 million (July 2013 estimate). According to the 2011 census, Sunni Muslims constitute 90 percent and Hindus make up 9.5 percent of the total population. The remainder of the population is predominantly Christian (mostly Roman Catholic) and Theravada-Hinayana Buddhist.” (US Department of State (28 July 2014) 2013 Report on International Religious Freedom – Bangladesh, p.1) A document published on the Life & Work in Dhaka website refers to Buddhism in Bangladesh as follows: “Theravanda is the oldest surviving Buddhist school, with over 100 million followers worldwide. In the hill tracts these predominantly consist of Chakma, Chak, Marma, Tenchungya and Khyang people. There are several monasteries in the Chittagong Hills, and a beautiful Golden Temple right here in Bandarban, which houses one of the largest statues of Buddha in the entire country. To be precise it is actually a pagoda, as the building itself consists of many tiered towers. Local Buddhist shrines also form an important centre for village life, with major festivals commemorating the important events in the life of the Buddah. Most Buddhist villages have a boarding school known as the ‘kyong,’ where boys learn to read Burmese and a little Pali, an ancient Buddhist scriptural language. -

The Propagation of Theravada Buddhism in Foreign Countries: the Case of the Dhammakaya Temple in Thailand

The propagation of Theravada Buddhism in foreign countries: The Case of the Dhammakaya Temple in Thailand Komazawa University Hidetake YANO This paper examines the organization, management, and propagation of the Wat Phra Dhammakaya (Dhammakaya Temple) in foreign countries, which is a newly arisen Buddhist group in Thailand. This group started its activity in 1970, and in 1977 it was recognized by the Thai government as a formal Buddhist temple belonging to the Sangha of Thai Theravada Buddhism. For this reason, it is difficult to term the Wat Phra Dhammakaya as a New Religious Movement. However, this temple has unique meditation practices, and its doctrines regarding Nirvana are different from mainstream Theravada Buddhism, hence, it is categorized as a new type of Buddhism in the Thai Buddhist Sangha. In orthodox forms of meditation in Theravada Buddhism, one starts with concentration on one’s own breathing or on one’s senses and emotions, then moves to the monitoring of and detachment from of the senses and emotions. However in the Dhammakaya style of meditation, one starts from meditating on a light (sphere) crystal ball or on a Buddha image in their mind, then cultivates the inner self along various stages that eventually lead to Dhammakaya, the Dharma body. This meditation aims to achieve “Nirvana” as the “true self” through the experience of unity with the Dhammakaya in the mind. Furthermore, it is believed that Dhammakaya meditation produces supernatural powers of protection and worldly happiness. Most of the members of this temple belong to the new urban middle class, who have a higher educational level, it has also spread to urbanites with less education and to the local people. -

Print This Article

Journal of Global Buddhism 2020, Vol.21 205–222 DOI: 10.5281/zenodo.4031015 www.globalbuddhism.org ISSN: 1527-6457 (online) © The author(s) Special Focus: Bad Buddhism This article illustrates how conversations on “good” and “bad” forms of Buddhism have taken place in Bangladesh since the 19th-century Theravāda reformation. First, in the process of purging prior Hindu and Tantric influences, second, with the introduction of Mahāyāna Buddhism through Risshō-Kōsei-kai; and, third, in responding to recent Buddhist extremism in Myanmar. The article also shows how “bad Buddhism”—for instance, Buddhist extremism in Myanmar—impacts Buddhists in other countries. For Bangladeshi Buddhists, claiming their identity and practices involves a process of both connecting with the “good” and distancing from the “bad.” Keywords: Bangladesh; Rissho-Kōshei Kai; Rohingya; global religion he Buddhist community forms a very small minority in Bangladesh, only approximately one percent of the total population of 160 million. Bangladeshi Buddhists mainly have been following Theravāda Buddhism, after a reformation initiated by the Arakanese Buddhist Tmonk Sāramedha Mahāthera and Buddhist priests of Chittagong, when Bangladesh was still a region of British India (Chakma 2011; Khan 2003; Chaudhuri 1982). Since the reformation movement began in 1856, the culture and practices of Bangladeshi Buddhists have been reshaped by many transnational influences. I argue in this paper that transnational connections have played a significant role in the formation of Bangladeshi Buddhist identity and practices, in the way they came to define “good” and “bad” forms of Buddhism. Bangladeshi Buddhists’ connections with Buddhists of other countries required them to be receptive to cultures and texts from outside which were then fused into the existing literary, geographical, economic, and political conditions of Bangladesh. -

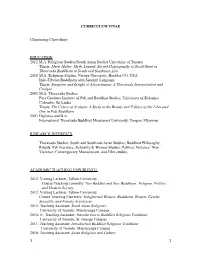

Chipamong Chowdhury EDUCATION 2012 MA

CURRICULUM VITAE Chipamong Chowdhury EDUCATION 2012 M.A. Religious Studies/South Asian Studies University of Toronto Thesis: Merit Maker: Myth, Legend, Sacred Hagiography of Sivali-Saint in Theravada Buddhism in South and Southeast Asia. 2010 M.A. Religious Studies, Naropa University, Boulder CO. USA Indo-Tibetan Buddhism with Sanskrit Language Thesis: Inception and Insight of Alayavijnana: A Theravada Interpretation and Critique. 2005 M.A. Theravada Studies Post Graduate Institute of Pali and Buddhist Studies, University of Kelaniya Colombo, Sri Lanka Thesis: The Colors of Arahant: A Study in the Beauty and Fallacy of the Liberated One in Pali Buddhism 2003 Diploma and B.A. International Theravada Buddhist Missionary University, Yangon, Myanmar. RESEARCH INTERESTS Theravada Studies; South and Southeast Asian Studies; Buddhist Philosophy; Rituals; Pali literature; Sexuality & Women Studies; Politics, Violence/ Non- Violence; Contemporary Monasticism; and Film studies. ACADEMIC TEACHING EXPERIENCE 2012: Visiting Lecturer, Tallinn University Course Teaching currently: Neo Buddha and New Buddhism: Religion, Politics, and Modern Society 2012: Visiting Lecturer, Tallinn University Course Teaching Currently: Enlightened Women: Buddhism, Women, Gender, Sexuality, and Female Asceticism 2012: Teaching Assistant: South Asian Religions. University of Toronto. Mississauga Campus. 2010-11: Teaching Assistant: Introduction to Buddhist Religious Traditions University of Toronto, St. George Campus 2011: Teaching Assistant: Introduction Buddhist Religious Traditions University of Toronto. Mississauga Campus 2010: Teaching Assistant: Asian Religions and Culture 1 1 University of Toronto, Scarborough Campus 2010: Teaching Assistant: Introduction Buddhist Religious Traditions University of Toronto, Mississauga Campus 2010: Introduction to World Religions, New Vista High School, Boulder, Colorado, USA. From March-May INVITED TO GIVE LECTURES 2011: What He Can/Can’t Do: Bodhisattva in Jataka-Narratives and Contemporary Practices in Southeast Asia. -

Buddhism and Politics the Politics of Buddhist Relic Diplomacy Between Bangladesh and Sri Lanka

Special Issue: Buddhism and Politics Journal of Buddhist Ethics ISSN 1076-9005 http://blogs.dickinson.edu/buddhistethics/ Volume 25, 2018 The Politics of Buddhist Relic Diplomacy Between Bangladesh and Sri Lanka D. Mitra Barua Cornell University Copyright Notice: Digital copies of this work may be made and distributed provided no change is made and no alteration is made to the content. Reproduction in any other format, with the exception of a single copy for private study, requires the written permission of the author. All en- quiries to: [email protected]. The Politics of Buddhist Relic Diplomacy Between Bangladesh and Sri Lanka D. Mitra Barua 1 Abstract Buddhists in Chittagong, Bangladesh claim to preserve a lock of hair believed to be of Sakyamuni Buddha himself. This hair relic has become a magnet for domestic and transnational politics; as such, it made journeys to Colom- bo in 1960, 2007, and 2011. The states of independent Cey- lon/Sri Lanka and East Pakistan/Bangladesh facilitated all three international journeys of the relic. Diplomats from both countries were involved in extending state invita- 1 The Robert H. N. Ho Family Foundation Postdoctoral Fellow, Cornell University. Email: [email protected]. The initial version of this article was presented at the confer- ence on “Buddhism and Politics” at the University of British Columbia in June 2014. It derives from the section of Buddhist transnational networks in my ongoing research project on Buddhism in Bengal. I am grateful to the Robert H. N. Ho Family Foundation Postdoctoral Fellowship in Buddhist Studies (administered by the American Council of Learned Societies) for its generous funding that has enabled me to conduct the re- search. -

Syllabus Department of Pali

NATIONAL UNIVERSITY Syllabus Department of Pali Four Year B.A Honours Course Effective from the Session : 2009–2010 National University Subject: Pali Syllabus for Four Year B. A Honours Course Effective from the Session: 2009-2010 Third Year (Honours) Course Code Course Title Marks Credits 1472 History of Buddhism in India 100 4 1473 Buddhist Sanskrit Literature 100 4 1474 Comparative Philology, Linguistics and Translation 100 4 1475 Pali Prosody, Phetoric, Essay and Amplification 100 4 1476 Non-Cononical Pali Literature 100 4 1477 Suttapitak: Jataka and Apadana Literature 100 4 1478 Pali Vamsa Literature 100 4 1479 Introduction to Theravade Buddhist Philosophy 100 4 Total = 800 32 2 Course Code 1472 Marks: 100 Credits: 4 Class Hours: 60 Course Title: History of Buddhism in India 1. Pre-Buddhistic history of political, religious and social conditions. 2. The history of Buddhism from Buddha to Pala Dynasty (Bimbisara, Prasenjit, Ajatasatru, Udyan, Kalasoka, Mauriyan period – Asoka, Kanishka, Harsavardhan, Gupta-period and Pala period). 3. Rise and decline of Buddhism in India and contribution of kings and setthis. Books Recommended 1. H.C. Roy chowdhury – Political History of Ancient India. 2. V.A. Smith – Early History of India (Part -VI) 3. B.C. Law: Historical Geography of Early Buddhism. 4. H.C. Hazra – Royal Patronage of Buddhism in Ancient India. 5. Lama Chimba and Alak Chatto padhyay (tr) -Taranath’s History of Buddhism in India. 6. Nihar Ranjan Roy – Bangalir Itihas – (Beng.) 7. R. C. Majumder – Banglar Itihas (Beng.) 8. Sukomal Chowdhury – Contemporary Buddhism in Bangladesh. 9. Gopal Chandra Haldar – Bharatbarser Itihas (Beng.) 10.