The Global Connections of Gandhāran Art

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Buddhist Discussion Centre (Upwey) Ltd. 33 Brooking St

Buddhist Discussion Centre (Upwey) Ltd. 33 Brooking St. Upwey 3158 Victoria Australia. Telephone 754 3334. (Incorporated in Victoria) NEWSLETTER N0. 11 MARCH 1983 REGISTERED BY AUSTRALIA POST PUBLICATION NO. VAR 3103 ISSN 0818-8254 Inauguration of 1000th Birth Anniversary of Atisa Dipankar Srijnan - Dhaka, Bangladesh,1983. Chief Martial Law Administrator, (C.M.L.A.) Lt. Gen. H. M. Ershad inaugurated the Week-long programme commencing on 26th February, 1983. A full report of this event appeared in the Bangladesh Observer, 20th February, 1983, at Page 1, under the heading "All Religions enjoy equal rights". The C.M.L.A. said it was a matter of great pride that Atisa Dipankar Srijnan had established Bangladesh in the comity of nations an honourable position by his unique contributions in the field of knowledge. Therefore, Dipankar is not only the asset and pride of the Buddhist community; rather he is the pride of Bangladesh and an asset for the whole nation. The C.M.L.A. hoped that the people being imbibed with the ideals of sacrifice, patriotism, friendship and love of mankind of Atisa Dipankar would take part in the greater struggle of building the nation. He called upon the participating delegates to carry with them the message of peace, fraternity, brotherhood, love and non-violence from the people of Bangladesh to the people of their respective countries. Besides Bangladesh, about 50 delegates from about 20 countries took part in the celebration. John D. Hughes, Director of B.D.C. (Upwey), representing Australia at the Conference, would like to express his sincere gratitude to the C.M.L.A. -

Gandharan Origin of the Amida Buddha Image

Ancient Punjab – Volume 4, 2016-2017 1 GANDHARAN ORIGIN OF THE AMIDA BUDDHA IMAGE Katsumi Tanabe ABSTRACT The most famous Buddha of Mahāyāna Pure Land Buddhism is the Amida (Amitabha/Amitayus) Buddha that has been worshipped as great savior Buddha especially by Japanese Pure Land Buddhists (Jyodoshu and Jyodoshinshu schools). Quite different from other Mahāyāna celestial and non-historical Buddhas, the Amida Buddha has exceptionally two names or epithets: Amitābha alias Amitāyus. Amitābha means in Sanskrit ‘Infinite light’ while Amitāyus ‘Infinite life’. One of the problems concerning the Amida Buddha is why only this Buddha has two names or epithets. This anomaly is, as we shall see below, very important for solving the origin of the Amida Buddha. Keywords: Amida, Śākyamuni, Buddha, Mahāyāna, Buddhist, Gandhara, In Japan there remain many old paintings of the Amida Triad or Trinity: the Amida Buddha flanked by the two bodhisattvas Avalokiteśvara and Mahāsthāmaprāpta (Fig.1). The function of Avalokiteśvara is compassion while that of Mahāsthāmaprāpta is wisdom. Both of them help the Amida Buddha to save the lives of sentient beings. Therefore, most of such paintings as the Amida Triad feature their visiting a dying Buddhist and attempting to carry the soul of the dead to the AmidaParadise (Sukhāvatī) (cf. Tangut paintings of 12-13 centuries CE from Khara-khoto, The State Hermitage Museum 2008: 324-327, pls. 221-224). Thus, the Amida Buddha and the two regular attendant bodhisattvas became quite popular among Japanese Buddhists and paintings. However, the origin of this Triad and also the Amida Buddha himself is not clarified as yet in spite of many previous studies dedicated to the Amida Buddha, the Amida Triad, and the two regular attendant bodhisattvas (Higuchi 1950; Huntington 1980; Brough 1982; Quagliotti 1996; Salomon/Schopen 2002; Harrison/Lutczanits 2012; Miyaji 2008; Rhi 2003, 2006). -

Colonialism, Education and Rural Buddhist Communities in Bangladesh Bijoy Barua University of Toronto, Canada, [email protected]

International Education Volume 37 Issue 1 Fall 2007 Colonialism, Education and Rural Buddhist Communities in Bangladesh Bijoy Barua University of Toronto, Canada, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://trace.tennessee.edu/internationaleducation Copyright © 2007 by the University of Tennessee. Reproduced with publisher's permission. Further reproduction of this article in violation of the copyright is prohibited. http://trace.tennessee.edu/internationaleducation/vol37/iss1/4 Recommended Citation Barua, Bijoy (2007). Colonialism, Education and Rural Buddhist Communities in Bangladesh. International Education, Vol. 37 Issue (1). Retrieved from: http://trace.tennessee.edu/internationaleducation/vol37/iss1/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Trace: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in International Education by an authorized administrator of Trace: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Barua COLONIALISM, EDUCATION, AND RURAL BUDDHIST COMMUNITIES IN BANGLADESH Bijoy Barua Ontario Institute for Studies in Education University of Toronto Toronto, Canada Cultural homogenization through the establishment of a central- ized and standardized curriculum in education has become the dominant model in Bangladesh today, a model of education that is deeply rooted in the colonial legacy of materialism, acquisitiveness, and social exclusion (B. Barua, 2004; Gustavsson, 1990). Such a model is predicated on the notion that Bangladesh “is culturally homogenous, with one language, one domi- nant religion, and no ethnic conflict” (Hussain, 2000, p. 52). Predictably and unfortunately, the prospects for decolonization in a “post-colonial/in- dependence context” still appear to be bleak since the state continues to rely on a centrally controlled and standardized educational system that is committed to cultural homogenization and social exclusion—a process that is being encouraged by foreign aid and international assistance (B. -

Appendix: 3 a List of Museums in Gujarat

Appendix: 3 A List of Museums in Gujarat Sr. Year of Name of Museum Governing Bodies No. Establishment 1. Kutch Museum, Bhuj 1877 Govt, of Gujarat 2. Barton Museum, Bhavnagar 1882 Govt, of Gujarat 3. Watson Museum, Rajkot 1888 Govt, of Gujarat 4. Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel Museum, 1890 Muni. Corpo., Surat Surat 5. Baroda Museum and Picture Gallery, 1894 Govt of Gujarat Vadodara 6. Junagadh Museum, Junagadh 1901 Govt, of Gujarat 7. Lady Wilson Museum, Dharampur 1928 Govt, of Gujarat (Dist. Valsad) 8. Health Museum, Vadodara 1937 Municipal Corporation 9. Archaeological Museum, Jamnagar 1946 10. B. J. Medical College Museum, 1946 Ahmedabad 11. Calico Museum of Textile, 1948 Trust Ahmedabad 12. University Museum, 1949 University Vallabh Vidhyanagar 13. Gandhi Memorian Residential 1950 Trust Museum (Kirti Mandir), Porbandar 14. Prabhas Patan Museum, Prabhas 1951 Govt, of Gujarat Patan 303 15. Shri Girdharbhai Children Museum, 1955 Trust Museum Amreli 16. Museum Department of 1956 University Archaeology, M.S. University of Baroda 17. City Museum, Ahmedabad 1957 Municipal Corporation 18. Dhirajben Bal Sangrahalay, 1959 Trust Kapadvanj 19. N.C. Mehta Gallery, Ahmedabad 1960 Trust 20. Gandhi Smirti Museum, Bhavnagar 1960 Trust 21. B. J. Institute Museum, Ahmedabad 1993 Trust 22. Shri Rajnikant Parekh Art and KB. 1960 Trust Parekh Commerce College, Khambhat 23. Maharaja Fatesing Museum, 1961 Trust Vadodara 24. Tribal Museum, Gujarat Vidhyapith, 1963 University Ahmedabad 25. Gandhi Memorial Museum, 1963 Trust Ahmedabad 26. Shri Ambalal Ranchchoddas Sura 1965 Trust Museum, Modasa 27. Karamchand Gandhi Memorial, 1969 Trust Rajkot 28. Lothal Museum, Lothal 1970 Govt, of India 29. Saputara Museum, Saputara 1970 Govt, of Gujarat 30. -

Gujarat Cotton Crop Estimate 2019 - 2020

GUJARAT COTTON CROP ESTIMATE 2019 - 2020 GUJARAT - COTTON AREA PRODUCTION YIELD 2018 - 2019 2019-2020 Area in Yield per Yield Crop in 170 Area in lakh Crop in 170 Kgs Zone lakh hectare in Kg/Ha Kgs Bales hectare Bales hectare kgs Kutch 0.563 825.00 2,73,221 0.605 1008.21 3,58,804 Saurashtra 19.298 447.88 50,84,224 18.890 703.55 78,17,700 North Gujarat 3.768 575.84 12,76,340 3.538 429.20 8,93,249 Main Line 3.492 749.92 15,40,429 3.651 756.43 16,24,549 Total 27.121 512.38 81,74,214 26.684 681.32 1,06,94,302 Note: Average GOT (Lint outturn) is taken as 34% Changes from Previous Year ZONE Area Yield Crop Lakh Hectare % Kgs/Ha % 170 kg Bales % Kutch 0.042 7.46% 183.21 22.21% 85,583 31.32% Saurashtra -0.408 -2.11% 255.67 57.08% 27,33,476 53.76% North Gujarat -0.23 -6.10% -146.64 -25.47% -3,83,091 -30.01% Main Line 0.159 4.55% 6.51 0.87% 84,120 5.46% Total -0.437 -1.61% 168.94 32.97% 25,20,088 30.83% Gujarat cotton crop yield is expected to rise by 32.97% and crop is expected to increase by 30.83% Inspite of excess and untimely rains at many places,Gujarat is poised to produce a very large cotton crop SAURASHTRA Area in Yield Crop in District Hectare Kapas 170 Kgs Bales Lint Kg/Ha Maund/Bigha Surendranagar 3,55,100 546.312 13.00 11,41,149 Rajkot 2,64,400 714.408 17.00 11,11,115 Jamnagar 1,66,500 756.432 18.00 7,40,858 Porbandar 9,400 756.432 18.00 41,826 Junagadh 74,900 756.432 18.00 3,33,275 Amreli 4,02,900 756.432 18.00 17,92,744 Bhavnagar 2,37,800 756.432 18.00 10,58,115 Morbi 1,86,200 630.360 15.00 6,90,430 Botad 1,63,900 798.456 19.00 7,69,806 Gir Somnath 17,100 924.528 22.00 92,997 Devbhumi Dwarka 10,800 714.408 17.00 45,386 TOTAL 18,89,000 703.552 16.74 78,17,700 1 Bigha = 16 Guntha, 1 Hectare= 6.18 Bigha, 1 Maund= 20 Kg Saurashtra sowing area reduced by 2.11%, estimated yield increase 57.08%, estimated Crop increase by 53.76%. -

He Noble Path

HE NOBLE PATH THE NOBLE PATH TREASURES OF BUDDHISM AT THE CHESTER BEATTY LIBRARY AND GALLERY OF ORIENTAL ART DUBLIN, IRELAND MARCH 1991 Published by the Trustees of the Chester Beatty Library and Gallery of Oriental Art, Dublin. 1991 ISBN:0 9517380 0 3 Printed in Ireland by The Criterion Press Photographic Credits: Pieterse Davison International Ltd: Cat. Nos. 5, 9, 12, 16, 17, 18, 21, 22, 25, 26, 27, 29, 32, 36, 37, 43 (cover), 46, 50, 54, 58, 59, 63, 64, 65, 70, 72, 75, 78. Courtesy of the National Museum of Ireland: Cat. Nos. 1, 2 (cover), 52, 81, 83. Front cover reproduced by kind permission of the National Museum of Ireland © Back cover reproduced by courtesy of the Trustees of the Chester Beatty Library © Copyright © Trustees of the Chester Beatty Library and Gallery of Oriental Art, Dublin. Chester Beatty Library 10002780 10002780 Contents Introduction Page 1-3 Buddhism in Burma and Thailand Essay 4 Burma Cat. Nos. 1-14 Cases A B C D 5 - 11 Thailand Cat. Nos. 15 - 18 Case E 12 - 14 Buddhism in China Essay 15 China Cat. Nos. 19-27 Cases F G H I 16 - 19 Buddhism in Tibet and Mongolia Essay 20 Tibet Cat. Nos. 28 - 57 Cases J K L 21 - 30 Mongolia Cat. No. 58 Case L 30 Buddhism in Japan Essay 31 Japan Cat. Nos. 59 - 79 Cases M N O P Q 32 - 39 India Cat. Nos. 80 - 83 Case R 40 Glossary 41 - 48 Suggestions for Further Reading 49 Map 50 ■ '-ie?;- ' . , ^ . h ':'m' ':4^n *r-,:«.ria-,'.:: M.,, i Acknowledgments Much credit for this exhibition goes to the Far Eastern and Japanese Curators at the Chester Beatty Library, who selected the exhibits and collaborated in the design and mounting of the exhibition, and who wrote the text and entries for the catalogue. -

Architectural Science in Jain Poetry: the Descriptions of Kumarapala's

International Journal of Jaina Studies (Online) Vol. 13, No. 4 (2017) 1-30 ARCHITECTURAL SCIENCE IN JAIN POETRY THE DESCRIPTIONS OF KUMARAPALA’S TEMPLES Basile Leclère 1. Introduction In the fourth act of the Moharājaparājaya or Defeat of King Delusion, a play about the conversion to Jainism of the Caulukya king Kumārapāla (r. 1143-1173) written by the Jain layman Yaśaḥpāla under the reign of Kumārapāla’s successor Ajayapāla (r. 1173-1176), there is a scene wherein several allegorical characters, Prince Gambling, his wife Falsehood and his friends Venison and Excellent-Wine are suddenly informed by a royal proclamation that a Jain festival is about to take place. Understanding that their existence is threatened by the king’s commitment to the ethics of Jainism, all these vices look in panic for a place in the capital city of Aṇahillapura (modern Patan) to take refuge in. Falsehood then points at a great temple where she thinks they could revel, but she learns from her husband that it is a Jain sanctuary totally unfit for welcoming them, as well as the many other charming temples that Falsehood notices in the vicinity. Prince Gambling and Excellent-Wine then explain that all these temples have been built by Kumārapāla under the influence of his spiritual teacher, the Jain monk Hemacandra.1 As a matter of fact, Kumārapāla did launch an ambitious architectural project after converting to Jainism and had Jain temples built all over the Caulukya empire, a feat celebrated by another allegorical character, Right-Judgement, in the fifth act of the Defeat of King Delusion: there he expresses his joy of seeing the earth looking like a woman thrilled with joy, with all these temples to Dispassionate Jinas erected at a high level as the hair of a body.2 Other Jain writers from the times of Kumārapāla similarly praised the king’s decision to manifest the social and political rise of Jainism by filling the landscape with so many temples. -

The Image of the Mystic Flower Exploring the Lotus Symbolism in the Bahá’Í House of Worship Julie Badiee*

The Image of the Mystic Flower Exploring the Lotus Symbolism in the Bahá’í House of Worship Julie Badiee* Abstract The most recently constructed Bahá’í House of Worship, situated in Bahapur, India, was dedicated in December 1985. The attractive and compelling design of this building creates the visual effect of a large, white lotus blossom appearing to emerge from the pools of water circled around it. The lotus flower, identified by the psychiatrist Carl Jung as an archetypal symbol, carries with it many meanings. This article will explore these meanings both in the traditions of the Indian subcontinent and in other cultures and other eras. In addition, the article will show that the flower imagery relates also to symbols employed in the Bahá’í Writings and, while reiterating the meanings of the past, also functions as a powerful image announcing the appearance of Bahá’u’lláh, the Manifestation of God for this day. Résumé La maison d’adoration bahá’íe la plus récente, située à Bahapur en Inde, a été dédiée en décembre 1985. Par sa conception attrayante et puissante, l’édifice semble émerger, telle une immense fleur de lotus blanche, des étangs qui l’entourent. La fleur de lotus, désignée comme symbole archétype par le psychiatre Carl Jung, porte en elle beaucoup de significations. Le présent article explore ses significations dans les traditions du sous-continent indien aussi bien que dans d’autres cultures et à d’autres époques. De plus, l’article montre que l’image de la fleur se retrouve également dans le langage symbolique employé dans les écrits bahá’ís. -

For Immediate Release February 22, 2006

For Immediate Release February 22, 2006 Contact: Bendetta Roux 212.636.2680 [email protected] SPLENDID MIRSKY COLLECTION HIGHLIGHTS INDIAN AND SOUTHEAST ASIAN ART SALE Indian and Southeast Asian Art March 30, 2006 New York – The final day of Christie’s Asian Art series will offer Indian and Southeast Asian Art, with the classical art offered in the morning and an afternoon sale devoted entirely to Modern and Contemporary Indian Art with its own catalogue (see separate release). The collecting field of traditional Indian and Southeast Asian works of art continues to gain momentum as collectors from other categories find their way into the serene and powerful worlds of Khmer or Chola sculpture. A superb collection of this kind, astonishing in its breadth and beauty, is The Alfred E. Mirsky Collection sold to benefit the Graduate Student Program of The Rockefeller University, which will lead the sale, along with property from various other private collections, as well as some unusual pieces that are being de-accessioned by the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Alfred Ezra Mirsky (1900–74) was one of those rare collectors blessed with great scientific acumen and a discriminating taste for the rare and beautiful. Professor Mirsky was a pioneering biochemist whose scientific accomplishments were matched by a profound interest in art and archaeology. His collection included Greek sculpture, Chinese paintings and pottery, Islamic pottery and especially Indian and Southeast Asian sculpture. Extraordinary for its sophistication, the collection combined pieces of great rarity and exceptional beauty. In accordance with the wishes of Dr. Mirsky and his wife Sonya, the proceeds from the sale of this collection will support the university’s graduate student program. -

Shri Prahlad Singh Patel

GOVERNMENT OF INDIA MINISTRY OF CULTURE LOK SABHA STARRED QUESTION NO. *197 TO BE ANSWERED ON 8.3.2021 ARCHAEOLOGICAL EXCAVATION IN MADHYA PRADESH *197. SHRI VISHNU DATT SHARMA: Will the Minister of Culture be pleased to state: (a) the number of places across the country where archaeological excavation work is being carried out; (b) the outcome of the said work along with the State-wise details thereof including Madhya Pradesh; (c) whether there are many ancient temples of Gupta period in Mahakoshal region of Madhya Pradesh and if so, the details thereof; (d) whether some relics like sculptures, columns, utensils and other artifacts have been recovered during excavation work carried out recently near Chaunsath Yogini Temple in Jabalpur which shows that there was an organized/ systematic settlement at the said place during the Stone Age till 12th and 13th Centuries; and (e) if so, the details thereof? ANSWER THE MINISTER OF STATE (INDEPENDENT CHARGE) FOR CULTURE & TOURISM (SHRI PRAHLAD SINGH PATEL) (a) A statement is laid on the table of the House. to (e) STATEMENT REFERRED TO IN REPLY PART (A) TO (E) OF THE LOK SABHA STARRED QUESTION NO. *197 FOR 8.3.2021 (a) The excavations carried out by the Archaeological Survey of India at present is & at Annexure I. (b) (c) Following three temples of Gupta period in Mahakoshal region of Madhya Pradesh are protected by the ASI: i. Temple of Somnath and ruins of several temples, district Katani, ii. Ruined temple near the sources of the Ken river, district Katani iii. The whole site of Kankali Devi Temple including the Devi temple and Ruined temple close to them, district Katani (d) Yes, Sir. -

Pakistan Heritage

VOLUME 8, 2016 ISSN 2073-641X PAKISTAN HERITAGE Editors Shakirullah and Ruth Young Research Journal of the Department of Archaeology Hazara University Mansehra-Pakistan Pakistan Heritage is an internationally peer reviewed research journal published annually by the Department of Archaeology, Hazara University Mansehra, Pakistan with the approval of the Vice Chancellor. No part in of the material contained in this journal should be reproduced in any form without prior permission of the editor (s). Price: PKR 1500/- US$ 20/- All correspondence related to the journal should be addressed to: The Editors/Asst. Editor Pakistan Heritage Department of Archaeology Hazara University Mansehra, Pakistan [email protected] [email protected] Editors Dr. Shakirullah Head of the Department of Archaeology Hazara University Mansehra, Pakistan Dr. Ruth Young Senior Lecturer and Director Distance Learning Strategies School of Archaeology and Ancient History University of Leicester, Leicester LE1 7RH United Kingdom Assistant Editor Mr. Junaid Ahmad Lecturer, Department of Archaeology Hazara University Mansehra, Pakistan Board of Editorial Advisors Pakistan Heritage, Volume 8 (2016) Professor Jonathan Mark Kenoyer, PhD Department of Anthropology, University of Wisconsin 1180 Observatory Drive, Madison,WI 53706-USA Professor Harald Hauptmann, PhD Heidelberg Academy of Science and Huinities Research Unit “Karakorum”, Karlstrass 4, D-69117, Heidelberg Germany Professor K. Karishnan, PhD Head, Department of Archaeology and Ancient History Maharaj Sayajirao -

Objectives the Main Objective of This Course Is to Introduce Students to Archaeology and the Methods Used by Archaeologists

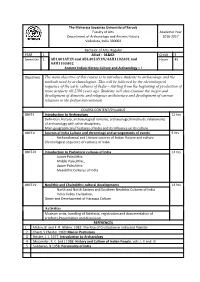

The Maharaja Sayajirao University of Baroda Faculty of Arts Academic Year Department of Archaeology and Ancient History 2016-2017 Vadodara, India 390002 Bachelor of Arts: Regular YEAR 1 Allied - 01&02: Credit 3 Semester 1 AB1A01AY1N and AB1A02AY1N/AAH1102A01 and Hours 45 AAH1103A02 Ancient Indian History Culture and Archaeology – I Objectives The main objective of this course is to introduce students to archaeology and the methods used by archaeologists. This will be followed by the chronological sequence of the early cultures of India – starting from the beginning of production of stone artifacts till 2700 years ago. Students will also examine the origin and development of domestic and religious architecture and development of various religions in the Indian subcontinent COURSE CONTENT/SYLLABUS UNIT-I Introduction to Archaeology 12 hrs Definition, history, archaeological remains, archaeological methods, relationship of archaeology with other disciplines; Main geographical of features of India and its influence on its culture UNIT-II Sources of India Culture and chronology and arrangements of events 5 hrs Archaeological and Literary sources of Indian History and culture Chronological sequence of cultures of India UNIT-III Introduction to Prehistoric cultures of India 14 hrs Lower Paleolithic, Middle Paleolithic, Upper Paleolithic, Mesolithic Cultures of India UNIT-IV Neolithic and Chalcolithic cultural developments 14 hrs North and North Eastern and Southern Neolithic Cultures of India Indus Valley Civilization, Origin and Development of Harappa Culture Activities Museum visits, handling of Artefacts, registration and documentation of artefacts,Presentation and discussion REFERENCES 1 Allchin, B. and F. R. Allchin. 1982. The Rise of Civilization in India and Pakistan.