SITR-Vol5-FINAL-Web.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2011 Annual Report Panama Amphibian Rescue and Conservation Project

2011 ANNUAL REPORT PANAMA AMPHIBIAN RESCUE AND CONSERVATION PROJECT A project partnership between: Africam Safari, Cheyenne Mountain Zoo, Defenders of Wildlife, Houston Zoo, Smithsonian’s National Zoological Park, Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute, Summit Municipal Park and Zoo New England. MISSION Our mission is to rescue and establish assurance colonies of amphibian species that are in ex- treme danger of extinction throughout Panama. We will also focus our efforts and expertise on developing methodologies to reduce the impact of the amphibian chytrid fungus (Bd) so that one day captive amphibians may be re-introduced to the wild. VISION The Panama Amphibian Rescue and Conservation Project will be a sustainably financed, Pana- manian-led organization that has stemmed the tide of extinctions caused by amphibian chytrid fungus and other threats to amphibians. We will lead successful recovery programs for Pa- nama’s endangered amphibians and serve as an exemplary model that can be replicated to ad- dress the threat of chytridiomycosis to the survival of amphibians worldwide. Cover image: Wild Atelopus limosus in Central Panamaa 1 EXPEDITIONS In 2011, we conducted one expedition to Cerro Sapo in the Darien and secured an adequate founding population of toad mountain harlequin frogs (Atelpous certus). We also received news from collaborator Doug Woodhams that Bd was detected in Torti on the border of the Darien province in January 2010. We tried several times to get back to Cerro Pirre in the Darien region, but setbacks included flooding and re- ports of FARC activities in the area. As a result, we fo- cused the bulk of our efforts on central Panama with eight expeditions to the Mamoni River Valley, Cerro Brewster, Cerro Bruja and Chucunaque River Valley. -

Two Interspecific Amplexus of Smilisca Sila (Hylidae) with Strabomantis Bufoniformis and Craugastor Fitzingeri (Craugastoridae)

Herpetology Notes, volume 11: 167-169 (2018) (published online on 10 February 2018) Two interspecific amplexus of Smilisca sila (Hylidae) with Strabomantis bufoniformis and Craugastor fitzingeri (Craugastoridae) Ángel Sosa-Bartuano1,2,*, Yostin Jesús Añino Ramos2,3, Víctor Martínez Cortés5,6; Rogemif Daniel Fuentes4 and Humberto Fossatti6 Anurans generally use auditory, chemical and visual versant from central Panama to northern Colombia signals for species and sex recognition (Wells, 2007). and the middle Magdalena Valley (Köhler, 2011). This Several studies on sympatric anurans that reproduce species generally breeds during the dry season (January synchronously have concluded that differences in the to April), and males of this species call at night along mating call can serve as an important reproductive streams, but they do not form dense choruses (da Silva isolation mechanism (Blair, 1964; Duellman, 1967; Nunes, 1988). However, at high elevations they may Crump, 1971; Höld, 1977), however the advertisement sometimes breed during the rainy season (Duellman and call of a male can be masked by a noisy environment Trueb, 1966). Craugastor fitzingeri (Schmidt, 1857) is or by the calls of other species, which may lead to a direct developing frog of the Craugastoridae family, interspecific amplexus (Shahrudin, 2016). Other distributed from northeastern Honduras to northwestern situations, including overlapping in reproductive period, Colombia (Köhler, 2011). Both sexes are frequently low female availability, confusion of chemical signals, found at night in the understory vegetation 0.5 to 1.6 m low male selectivity, and explosive breeding behavior above ground often along forest edges. Males usually may also result in interspecific amplexus (Pearl et al., vocalize from elevated spots on stumps, fallen logs, and 2005; Wogel et al., 2005; Mollov et al., 2010; Machado low vegetation. -

And Wildlife, 1928-72

Bibliography of Research Publications of the U.S. Bureau of Sport Fisheries and Wildlife, 1928-72 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR BUREAU OF SPORT FISHERIES AND WILDLIFE RESOURCE PUBLICATION 120 BIBLIOGRAPHY OF RESEARCH PUBLICATIONS OF THE U.S. BUREAU OF SPORT FISHERIES AND WILDLIFE, 1928-72 Edited by Paul H. Eschmeyer, Division of Fishery Research Van T. Harris, Division of Wildlife Research Resource Publication 120 Published by the Bureau of Sport Fisheries and Wildlife Washington, B.C. 1974 Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Eschmeyer, Paul Henry, 1916 Bibliography of research publications of the U.S. Bureau of Sport Fisheries and Wildlife, 1928-72. (Bureau of Sport Fisheries and Wildlife. Kesource publication 120) Supt. of Docs. no.: 1.49.66:120 1. Fishes Bibliography. 2. Game and game-birds Bibliography. 3. Fish-culture Bibliography. 4. Fishery management Bibliogra phy. 5. Wildlife management Bibliography. I. Harris, Van Thomas, 1915- joint author. II. United States. Bureau of Sport Fisheries and Wildlife. III. Title. IV. Series: United States Bureau of Sport Fisheries and Wildlife. Resource publication 120. S914.A3 no. 120 [Z7996.F5] 639'.9'08s [016.639*9] 74-8411 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing OfTie Washington, D.C. Price $2.30 Stock Number 2410-00366 BIBLIOGRAPHY OF RESEARCH PUBLICATIONS OF THE U.S. BUREAU OF SPORT FISHERIES AND WILDLIFE, 1928-72 INTRODUCTION This bibliography comprises publications in fishery and wildlife research au thored or coauthored by research scientists of the Bureau of Sport Fisheries and Wildlife and certain predecessor agencies. Separate lists, arranged alphabetically by author, are given for each of 17 fishery research and 6 wildlife research labora tories, stations, investigations, or centers. -

N° English Name Scientific Name Status Day 1

1 FUNDACIÓN JOCOTOCO CHECK-LIST OF THE BIRDS OF YANACOCHA N° English Name Scientific Name Status Day 1 Day 2 Day 3 1 Tawny-breasted Tinamou Nothocercus julius R 2 Curve-billed Tinamou Nothoprocta curvirostris U 3 Torrent Duck Merganetta armata 4 Andean Teal Anas andium 5 Andean Guan Penelope montagnii U 6 Sickle-winged Guan Chamaepetes goudotii 7 Cattle Egret Bubulcus ibis 8 Black Vulture Coragyps atratus 9 Turkey Vulture Cathartes aura 10 Andean Condor Vultur gryphus R Sharp-shinned Hawk (Plain- 11 breasted Hawk) Accipiter striatus U 12 Swallow-tailed Kite Elanoides forficatus 13 Black-and-chestnut Eagle Spizaetus isidori 14 Cinereous Harrier Circus cinereus 15 Roadside Hawk Rupornis magnirostris 16 White-rumped Hawk Parabuteo leucorrhous 17 Black-chested Buzzard-Eagle Geranoaetus melanoleucus U 18 White-throated Hawk Buteo albigula R 19 Variable Hawk Geranoaetus polyosoma U 20 Andean Lapwing Vanellus resplendens VR 21 Rufous-bellied Seedsnipe Attagis gayi 22 Upland Sandpiper Bartramia longicauda R 23 Baird's Sandpiper Calidris bairdii VR 24 Andean Snipe Gallinago jamesoni FC 25 Imperial Snipe Gallinago imperialis U 26 Noble Snipe Gallinago nobilis 27 Jameson's Snipe Gallinago jamesoni 28 Spotted Sandpiper Actitis macularius 29 Band-tailed Pigeon Patagoienas fasciata FC 30 Plumbeous Pigeon Patagioenas plumbea 31 Common Ground-Dove Columbina passerina 32 White-tipped Dove Leptotila verreauxi R 33 White-throated Quail-Dove Zentrygon frenata U 34 Eared Dove Zenaida auriculata U 35 Barn Owl Tyto alba 36 White-throated Screech-Owl Megascops -

An Introduction to the Bofedales of the Peruvian High Andes

An introduction to the bofedales of the Peruvian High Andes M.S. Maldonado Fonkén International Mire Conservation Group, Lima, Peru _______________________________________________________________________________________ SUMMARY In Peru, the term “bofedales” is used to describe areas of wetland vegetation that may have underlying peat layers. These areas are a key resource for traditional land management at high altitude. Because they retain water in the upper basins of the cordillera, they are important sources of water and forage for domesticated livestock as well as biodiversity hotspots. This article is based on more than six years’ work on bofedales in several regions of Peru. The concept of bofedal is introduced, the typical plant communities are identified and the associated wild mammals, birds and amphibians are described. Also, the most recent studies of peat and carbon storage in bofedales are reviewed. Traditional land use since prehispanic times has involved the management of water and livestock, both of which are essential for maintenance of these ecosystems. The status of bofedales in Peruvian legislation and their representation in natural protected areas and Ramsar sites is outlined. Finally, the main threats to their conservation (overgrazing, peat extraction, mining and development of infrastructure) are identified. KEY WORDS: cushion bog, high-altitude peat; land management; Peru; tropical peatland; wetland _______________________________________________________________________________________ INTRODUCTION organic soil or peat and a year-round green appearance which contrasts with the yellow of the The Tropical Andes Cordillera has a complex drier land that surrounds them. This contrast is geography and varied climatic conditions, which especially striking in the xerophytic puna. Bofedales support an enormous heterogeneity of ecosystems are also called “oconales” in several parts of the and high biodiversity (Sagástegui et al. -

Ecuador: the Andes & Mindo December 1

Ecuador: The Andes & Mindo December 1 – 9, 2016 Experience Ecuador’s Andean beauty and amazing bird diversity: from the hummingbirds of Yanacocha to the cloud forests of Bella Vista. Explore Antisana Volcano and search for endemics of the Chocó region; this trip is a must for those keen to explore South America. Visit the east and west sides of two branches of the Andes and bird key hotspots at Silanche, Milpe, Mindo, Guango, San Isidro, Papallacta Pass, and Antisana Volcano. Ecuador’s cloud forests host rarities like Highland Tinamou, Greater Scythebill, Bicolored Antbird, and the Sword-billed Hummingbird ― the only bird with a bill longer than its body. Savor delightful eco-lodges in forests lush with orchids, bromeliads, and butterflies, browse colorful markets, and enjoy warm Ecuadorian hospitality. Extend your trip to one of the Amazonia lodges if you choose. Tour Highlights Explore the important Yanacocha Reserve, with hummingbirds — including the amazing Sword-billed — as the star attraction Relax at the lovely Sachatamia Lodge, located on a private reserve; legendary birding is just out your door Bird a private farm, famous for views of the often difficult Giant Antpitta and Andean Cock-of-the-Rock Discover the abundant species of the lush cloud forest, 5,000 – 7,000 feet above sea level Trek the tundra-like high paramo and enjoy views of the stunning (and snow-capped) Antisana Volcano; our eyes are peeled for Andean Condor Bird and botanize in the cloud forests of San Isidro; 310 species abound Naturalist Journeys, LLC / Caligo Ventures PO Box 16545 Portal, AZ 85632 PH: 520.558.1146 / 800.426.7781 Fax 650.471.7667www.naturalistjourneys.com / www.caligo.com [email protected] / [email protected] Tour Summary 9-Day / 8-Night Birding & Natural History Tour with Expert Local Guides $2750 from Quito Airport is Mariscal Sucre International (UIO) Itinerary Thurs., Dec. -

Ornithological Surveys in Serranía De Los Churumbelos, Southern Colombia

Ornithological surveys in Serranía de los Churumbelos, southern Colombia Paul G. W . Salaman, Thomas M. Donegan and Andrés M. Cuervo Cotinga 12 (1999): 29– 39 En el marco de dos expediciones biológicos y Anglo-Colombian conservation expeditions — ‘Co conservacionistas anglo-colombianas multi-taxa, s lombia ‘98’ and the ‘Colombian EBA Project’. Seven llevaron a cabo relevamientos de aves en lo Serranía study sites were investigated using non-systematic de los Churumbelos, Cauca, en julio-agosto 1988, y observations and standardised mist-netting tech julio 1999. Se estudiaron siete sitios enter en 350 y niques by the three authors, with Dan Davison and 2500 m, con 421 especes registrados. Presentamos Liliana Dávalos in 1998. Each study site was situ un resumen de los especes raros para cada sitio, ated along an altitudinal transect at c. 300- incluyendo los nuevos registros de distribución más m elevational steps, from 350–2500 m on the Ama significativos. Los resultados estabilicen firme lo zonian slope of the Serranía. Our principal aim was prioridad conservacionista de lo Serranía de los to allow comparisons to be made between sites and Churumbelos, y aluco nos encontramos trabajando with other biological groups (mammals, herptiles, junto a los autoridades ambientales locales con insects and plants), and, incorporating geographi cuiras a lo protección del marcizo. cal and anthropological information, to produce a conservation assessment of the region (full results M e th o d s in Salaman et al.4). A sizeable part of eastern During 14 July–17 August 1998 and 3–22 July 1999, Cauca — the Bota Caucana — including the 80-km- ornithological surveys were undertaken in Serranía long Serranía de los Churumbelos had never been de los Churumbelos, Department of Cauca, by two subject to faunal surveys. -

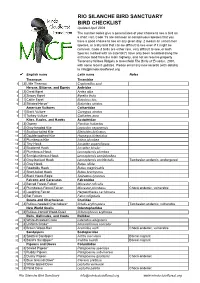

RIO SILANCHE BIRD SANCTUARY BIRD CHECKLIST Updated April 2008 the Number Codes Give a General Idea of Your Chance to See a Bird on a Short Visit

RIO SILANCHE BIRD SANCTUARY BIRD CHECKLIST Updated April 2008 The number codes give a general idea of your chance to see a bird on a short visit. Code 1's are common or conspicuous species that you have a good chance to see on any given day. 2 means an uncommon species, or a shy bird that can be difficult to see even if it might be common. Code 3 birds are either rare, very difficult to see, or both. Species marked with an asterisk(*) have only been recorded along the entrance road from the main highway, and not on reserve property. Taxonomy follows Ridgely & Greenfield The Birds of Ecuador , 2001, with some recent updates. Please email any new records (with details) to [email protected]. English name Latin name Notes Tinamous Tinamidae 1 3 Little Tinamou Crypturellus soui Herons, Bitterns, and Egrets Ardeidae 2 2 Great Egret Ardea alba 3 2 Snowy Egret Egretta thula 4 1 Cattle Egret Bubulcus ibis 5 3 Striated Heron* Butorides striatus American Vultures Cathartidae 6 1 Black Vulture Coragyps atratus 7 1 Turkey Vulture Cathartes aura Kites, Eagles, and Hawks Accipitridae 8 3 Osprey Pandion haliaetus 9 2 Gray-headed Kite Leptodon cayanensis 10 1 Swallow-tailed Kite Elanoides forficatus 11 2 Double-toothed Kite Harpagus bidentatus 12 2 Plumbeous Kite Ictinia plumbea 13 3 Tiny Hawk Accipiter superciliosus 14 3 Bicolored Hawk Accipiter bicolor 15 2 Plumbeous Hawk Leucopternis plumbea 16 3 Semiplumbeous Hawk Leucopternis semiplumbea 17 3 Gray-backed Hawk Leucopternis occidentalis Tumbesian endemic, endangered 18 2 Gray Hawk Buteo nitida -

Ecuador's Biodiversity Hotspots

Ecuador’s Biodiversity Hotspots Destination: Andes, Amazon & Galapagos Islands, Ecuador Duration: 19 Days Dates: 29th June – 17th July 2018 Exploring various habitats throughout the wonderful & diverse country of Ecuador Spotting a huge male Andean bear & watching as it ripped into & fed on bromeliads Watching a Eastern olingo climbing the cecropia from the decking in Wildsumaco Seeing ~200 species of bird including 33 species of dazzling hummingbirds Watching a Western Galapagos racer hunting, catching & eating a Marine iguana Incredible animals in the Galapagos including nesting flightless cormorants 36 mammal species including Lowland paca, Andean bear & Galapagos fur seals Watching the incredible and tiny Pygmy marmoset in the Amazon near Sacha Lodge Having very close views of 8 different Andean condors including 3 on the ground Having Galapagos sea lions come up & interact with us on the boat and snorkelling Tour Leader / Guides Overview Martin Royle (Royle Safaris Tour Leader) Gustavo (Andean Naturalist Guide) Day 1: Quito / Puembo Francisco (Antisana Reserve Guide) Milton (Cayambe Coca National Park Guide) ‘Campion’ (Wildsumaco Guide) Day 2: Antisana Wilmar (Shanshu), Alex and Erica (Amazonia Guides) Gustavo (Galapagos Islands Guide) Days 3-4: Cayambe Coca Participants Mr. Joe Boyer Days 5-6: Wildsumaco Mrs. Rhoda Boyer-Perkins Day 7: Quito / Puembo Days 8-10: Amazon Day 11: Quito / Puembo Days 12-18: Galapagos Day 19: Quito / Puembo Royle Safaris – 6 Greenhythe Rd, Heald Green, Cheshire, SK8 3NS – 0845 226 8259 – [email protected] Day by Day Breakdown Overview Ecuador may be a small country on a map, but it is one of the richest countries in the world in terms of life and biodiversity. -

COLOMBIA 2019 Ned Brinkley Departments of Vaupés, Chocó, Risaralda, Santander, Antioquia, Magdalena, Tolima, Atlántico, La Gu

COLOMBIA 2019 Ned Brinkley Departments of Vaupés, Chocó, Risaralda, Santander, Antioquia, Magdalena, Tolima, Atlántico, La Guajira, Boyacá, Distrito Capital de Bogotá, Caldas These comments are provided to help independent birders traveling in Colombia, particularly people who want to drive themselves to birding sites rather than taking public transportation and also want to book reservations directly with lodgings and reserves rather than using a ground agent or tour company. Many trip reports provide GPS waypoints for navigation. I used GoogleEarth/ Maps, which worked fine for most locations (not for El Paujil reserve). I paid $10/day for AT&T to hook me up to Claro, Movistar, or Tigo through their Passport program. Others get a local SIM card so that they have a Colombian number (cheaper, for sure); still others use GooglePhones, which provide connection through other providers with better or worse success, depending on the location in Colombia. For transportation, I used a rental 4x4 SUV to reach places with bad roads but also, in northern Colombia, a subcompact rental car as far as Minca (hiked in higher elevations, with one moto-taxi to reach El Dorado lodge) and for La Guajira. I used regular taxis on few occasions. The only roads to sites for Fuertes’s Parrot and Yellow-eared Parrot could not have been traversed without four-wheel drive and high clearance, and this is important to emphasize: vehicles without these attributes would have been useless, or become damaged or stranded. Note that large cities in Colombia (at least Medellín, Santa Marta, and Cartagena) have restrictions on driving during rush hours with certain license plate numbers (they base restrictions on the plate’s final numeral). -

ECUADOR: the Andes Introtour and High Andes Extension 10Th- 19Th November 2019

Tropical Birding - Trip Report Ecuador: The Andes Introtour, November 2019 A Tropical Birding SET DEPARTURE tour ECUADOR: The Andes Introtour and High Andes Extension th th 10 - 19 November 2019 TOUR LEADER: Jose Illanes Report and photos by Jose Illanes Andean Condor from Antisana National Park This is one Tropical Birding’s most popular tours and I have guided it numerous times. It’s always fun and offers so many memorable birds. Ecuador is a wonderful country to visit with beautiful landscapes, rich culture, and many friendly people that you will meet along the way. Some of the highlights picked by the group were Andean Condor, White-throated Screech-Owl, Giant Antpitta, Jameson’s Snipe, Giant Hummingbird, Black-tipped Cotinga, Sword-billed Hummingbird, Club-winged Manakin, Lyre-tailed Nightjar, Lanceolated Monklet, Flame-faced Tanager, Toucan Barbet, Violet-tailed Sylph, Undulated Antpitta, Andean Gull, Blue-black Grassquit, and the attractive Blue-winged Mountain-Tanager. Our total species count on the trip (including the extension) was around 368 seen and 31 heard only. www.tropicalbirding.com +1-409-515-9110 [email protected] p.1 Tropical Birding - Trip Report Ecuador: The Andes Introtour, November 2019 Torrent Duck at Guango Lodge on the extension November 11: After having arrived in Quito the night before, we had our first birding this morning in the Yanacocha Reserve owned by the Jocotoco Foundation, which is not that far from Ecuador’s capital. Our first stop was along the entrance road near a water pumping station, where we started out by seeing Streak- throated Bush-Tyrant, Brown-backed Chat-Tyrant, Cinereous Conebill, White-throated Tyrannulet, a very responsive Superciliaried Hemispingus, Black-crested Warbler, and the striking Crimson-mantled Woodpecker. -

Neotropical News Neotropical News

COTINGA 1 Neotropical News Neotropical News Brazilian Merganser in Argentina: If the survey’s results reflect the true going, going … status of Mergus octosetaceus in Argentina then there is grave cause for concern — local An expedition (Pato Serrucho ’93) aimed extinction, as in neighbouring Paraguay, at discovering the current status of the seems inevitable. Brazilian Merganser Mergus octosetaceus in Misiones Province, northern Argentina, During the expedition a number of sub has just returned to the U.K. Mergus tropical forest sites were surveyed for birds octosetaceus is one of the world’s rarest — other threatened species recorded during species of wildfowl, with a population now this period included: Black-fronted Piping- estimated to be less than 250 individuals guan Pipile jacutinga, Vinaceous Amazon occurring in just three populations, one in Amazona vinacea, Helmeted Woodpecker northern Argentina, the other two in south- Dryocopus galeatus, White-bearded central Brazil. Antshrike Biata s nigropectus, and São Paulo Tyrannulet Phylloscartes paulistus. Three conservation biologists from the U.K. and three South American counter PHIL BENSTEAD parts surveyed c.450 km of white-water riv Beaver House, Norwich Road, Reepham, ers and streams using an inflatable boat. Norwich, NR10 4JN, U.K. Despite exhaustive searching only one bird was located in an area peripheral to the species’s historical stronghold. Former core Black-breasted Puffleg found: extant areas (and incidently those with the most but seriously threatened. protection) for this species appear to have been adversely affected by the the Urugua- The Black-breasted Puffleg Eriocnemis í dam, which in 1989 flooded c.80 km of the nigrivestis has been recorded from just two Río Urugua-í.