June/July 2021

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Language in the USA

This page intentionally left blank Language in the USA This textbook provides a comprehensive survey of current language issues in the USA. Through a series of specially commissioned chapters by lead- ing scholars, it explores the nature of language variation in the United States and its social, historical, and political significance. Part 1, “American English,” explores the history and distinctiveness of American English, as well as looking at regional and social varieties, African American Vernacular English, and the Dictionary of American Regional English. Part 2, “Other language varieties,” looks at Creole and Native American languages, Spanish, American Sign Language, Asian American varieties, multilingualism, linguistic diversity, and English acquisition. Part 3, “The sociolinguistic situation,” includes chapters on attitudes to language, ideology and prejudice, language and education, adolescent language, slang, Hip Hop Nation Language, the language of cyberspace, doctor–patient communication, language and identity in liter- ature, and how language relates to gender and sexuality. It also explores recent issues such as the Ebonics controversy, the Bilingual Education debate, and the English-Only movement. Clear, accessible, and broad in its coverage, Language in the USA will be welcomed by students across the disciplines of English, Linguistics, Communication Studies, American Studies and Popular Culture, as well as anyone interested more generally in language and related issues. edward finegan is Professor of Linguistics and Law at the Uni- versity of Southern California. He has published articles in a variety of journals, and his previous books include Attitudes toward English Usage (1980), Sociolinguistic Perspectives on Register (co-edited with Douglas Biber, 1994), and Language: Its Structure and Use, 4th edn. -

China in 50 Dishes

C H I N A I N 5 0 D I S H E S CHINA IN 50 DISHES Brought to you by CHINA IN 50 DISHES A 5,000 year-old food culture To declare a love of ‘Chinese food’ is a bit like remarking Chinese food Imported spices are generously used in the western areas you enjoy European cuisine. What does the latter mean? It experts have of Xinjiang and Gansu that sit on China’s ancient trade encompasses the pickle and rye diet of Scandinavia, the identified four routes with Europe, while yak fat and iron-rich offal are sauce-driven indulgences of French cuisine, the pastas of main schools of favoured by the nomadic farmers facing harsh climes on Italy, the pork heavy dishes of Bavaria as well as Irish stew Chinese cooking the Tibetan plains. and Spanish paella. Chinese cuisine is every bit as diverse termed the Four For a more handy simplification, Chinese food experts as the list above. “Great” Cuisines have identified four main schools of Chinese cooking of China – China, with its 1.4 billion people, has a topography as termed the Four “Great” Cuisines of China. They are Shandong, varied as the entire European continent and a comparable delineated by geographical location and comprise Sichuan, Jiangsu geographical scale. Its provinces and other administrative and Cantonese Shandong cuisine or lu cai , to represent northern cooking areas (together totalling more than 30) rival the European styles; Sichuan cuisine or chuan cai for the western Union’s membership in numerical terms. regions; Huaiyang cuisine to represent China’s eastern China’s current ‘continental’ scale was slowly pieced coast; and Cantonese cuisine or yue cai to represent the together through more than 5,000 years of feudal culinary traditions of the south. -

Trendscape Report, Highlighting What Campbell’S Global Team of Chefs and Bakers See As the Most Dynamic Food Trends to Watch

Insights for Innovation and Inspiration from Thomas W. Griffiths, CMC Vice President, Campbell’s Culinary & Baking Institute (CCBI) Last year we published our first-ever Culinary TrendScape report, highlighting what Campbell’s global team of chefs and bakers see as the most dynamic food trends to watch. The response has been exceptional. The conversations that have taken place over the past year amongst our food industry friends and colleagues have been extremely rewarding. It has also been quite a thrill to see this trend-monitoring program take on a life of its own here at Campbell. Staying on the pulse of evolving tastes is inspiring our culinary team’s day-to- day work, driving us to lead innovation across company-wide business platforms. Most importantly, it is helping us translate trends into mealtime solutions that are meaningful for life’s real PICS moments. It’s livening up our lunch break conversations, too! TO OT H These themes are This 2015 Culinary TrendScape report offers a look at the year’s ten most exciting North 15 the driving force 0 American trends we’ve identified, from Filipino Flavors to Chile Peppers. Once again, 2 behind this year’s top trends we’ve developed a report that reflects our unique point of view, drawing on the expertise of our team, engaging culinary influencers and learning from trusted Authenticity industry partners. Changing Marketplace Just like last year, we took a look at overarching themes—hot topics—that are shaping Conscious Connections the ever-changing culinary landscape. The continued cultural transformation of retail Distinctive Flavors markets and restaurants catering to changing consumer tastes is clearly evident Elevated Simplicity throughout this year’s report. -

Bread Pudding-Nyt2009

As Published: January 27, 2009 FEED ME By ALEX WITCHEL Luxury Takes a Page From Frugality JELLY DOUGHNUT PUDDING RECIPE Adapted from Eli Zabar Time: About 2 1/2 hours Ingredients: 1. Heat oven to 325 degrees. Fill a kettle with water and 3 1/2 cups heavy place over high heat to bring to a boil. In a large mixing bowl, combine cream, milk, 1 1/2 cups sugar, eggs, egg yolks and cream, at room vanilla. Whisk to blend. temperature 2. Using a serrated knife, gently slice doughnuts from top to 1 1/2 cups whole milk, bottom in 1/4-inch slices. Butter a 9-by-12-inch baking pan at room temperature and sprinkle with 1 tablespoon sugar. Pour about 1/2 inch of the cream mixture into pan. Arrange a layer of sliced dough- nuts in pan, overlapping them slightly. Top with another layer, 1 1/2 cups plus pressing them down slightly to moisten them. Top with a 2 tablespoons sugar small amount of cream mixture. 8 large eggs 3. Arrange 2 more layers of sliced doughnuts, and pour remaining liquid evenly over top. Press down gently to mois- ten. Sprinkle with remaining 1 tablespoon sugar. Cover pan 4 large egg yolks tightly with foil, and place in a larger pan. Fill larger pan with boiling water until three-quarters up the side of pudding pan. 1 tablespoon vanilla extract 4. Bake for 1 hour 50 minutes. Remove foil and continue to bake until top is golden brown, about 15 minutes. Turn off oven, open door slightly, and leave in oven for an additional AN AFTERLIFE 14 jelly doughnuts, Unsold jelly donuts become a pudding at Eli’s Manhattan 10 minutes. -

Product List Winter 2020/21 2 Winter 2020/21 Winter 2017 3

Product List Winter 2020/21 2 Winter 2020/21 Winter 2017 3 Contents Large and Small meals Large and Small Meals Textured Modified A huge selection of mains, soups, Savoury Pastries 04 Level 3 (Liquidised) 22 sides and desserts – created to Breakfast 04 Level 4 (Puréed) 22 sustain and nourish patients. Soups 05 Level 4 (Purée Petite) 25 Main meals – Meat Level 5 (Minced & Moist) 26 • Beef 06 Level 6 (Soft & Bite-Sized) 27 • Poultry 06 • Pork 08 • Other Meat 08 Special Diets • Lamb & Mutton 09 Gluten free 29 Main Meals - Fish 09 Free From 30 Main Meals - Vegetarian 10 Mini Meals Extra 31 Sides Energy dense 32 • Accompaniments 11 Low & Reduced Sugars Individual Desserts 32 • Vegetables 12 Finger Foods 33 • Potatoes and Rice 13 Desserts Ethnic Meals • Hot Desserts 14 Kosher Meals 35 • Cold Desserts 16 Kosher Desserts 35 • Cakes 16 Caribbean & West Indian Meals 36 Asian Halal Meals 37 CarteChoix Asian Halal Vegetarian Meals 38 Main meals – Meat • Beef 18 Dietary Codes 39 • Lamb 18 • Poultry 18 • Pork 18 Main Meals - Fish 18 Main Meals - Vegetarian 18 Main Meals - iWave Recommended 19 Desserts • Hot desserts 19 Making food that tastes great and aids patient recovery has been our mission from day one. It’s what our registered dietitian and team of qualified chefs work tirelessly for. Whatever a patient’s dietary needs, ethnic preference or taste, it’s about offering them something good to eat. Our Dietitian, Emily Stuart, is a healthcare expert as well as a member Minced Beef Hotpot : 324112 of the BDA 4 Winter 2020/21 Large and Small Meals Winter -

Republic of Ireland. Wikipedia. Last Modified

Republic of Ireland - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia What links here Related changes Upload file Special pages Republic of Ireland Permanent link From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Page information Data item This article is about the modern state. For the revolutionary republic of 1919–1922, see Irish Cite this page Republic. For other uses, see Ireland (disambiguation). Print/export Ireland (/ˈaɪərlənd/ or /ˈɑrlənd/; Irish: Éire, Ireland[a] pronounced [ˈeː.ɾʲə] ( listen)), also known as the Republic Create a book Éire of Ireland (Irish: Poblacht na hÉireann), is a sovereign Download as PDF state in Europe occupying about five-sixths of the island Printable version of Ireland. The capital is Dublin, located in the eastern part of the island. The state shares its only land border Languages with Northern Ireland, one of the constituent countries of Acèh the United Kingdom. It is otherwise surrounded by the Адыгэбзэ Atlantic Ocean, with the Celtic Sea to the south, Saint Flag Coat of arms George's Channel to the south east, and the Irish Sea to Afrikaans [10] Anthem: "Amhrán na bhFiann" Alemannisch the east. It is a unitary, parliamentary republic with an elected president serving as head of state. The head "The Soldiers' Song" Sorry, your browser either has JavaScript of government, the Taoiseach, is nominated by the lower Ænglisc disabled or does not have any supported house of parliament, Dáil Éireann. player. You can download the clip or download a Aragonés The modern Irish state gained effective independence player to play the clip in your browser. from the United Kingdom—as the Irish Free State—in Armãneashce 1922 following the Irish War of Independence, which Arpetan resulted in the Anglo-Irish Treaty. -

The Columbian Exchange: a History of Disease, Food, and Ideas

Journal of Economic Perspectives—Volume 24, Number 2—Spring 2010—Pages 163–188 The Columbian Exchange: A History of Disease, Food, and Ideas Nathan Nunn and Nancy Qian hhee CColumbianolumbian ExchangeExchange refersrefers toto thethe exchangeexchange ofof diseases,diseases, ideas,ideas, foodfood ccrops,rops, aandnd populationspopulations betweenbetween thethe NewNew WorldWorld andand thethe OldOld WWorldorld T ffollowingollowing thethe voyagevoyage ttoo tthehe AAmericasmericas bbyy ChristoChristo ppherher CColumbusolumbus inin 1492.1492. TThehe OldOld WWorld—byorld—by wwhichhich wwee mmeanean nnotot jjustust EEurope,urope, bbutut tthehe eentirentire EEasternastern HHemisphere—gainedemisphere—gained fromfrom tthehe CColumbianolumbian EExchangexchange iinn a nnumberumber ooff wways.ays. DDiscov-iscov- eeriesries ooff nnewew ssuppliesupplies ofof metalsmetals areare perhapsperhaps thethe bestbest kknown.nown. BButut thethe OldOld WWorldorld aalsolso ggainedained newnew staplestaple ccrops,rops, ssuchuch asas potatoes,potatoes, sweetsweet potatoes,potatoes, maize,maize, andand cassava.cassava. LessLess ccalorie-intensivealorie-intensive ffoods,oods, suchsuch asas tomatoes,tomatoes, chilichili peppers,peppers, cacao,cacao, peanuts,peanuts, andand pineap-pineap- pplesles wwereere aalsolso iintroduced,ntroduced, andand areare nownow culinaryculinary centerpiecescenterpieces inin manymany OldOld WorldWorld ccountries,ountries, namelynamely IItaly,taly, GGreece,reece, andand otherother MediterraneanMediterranean countriescountries (tomatoes),(tomatoes), -

Holiday Dinner 2016

HOLIDAY DINNER 2016 ORDER DEPARTMENT: CUSTOMER NAME: Tel 212.717.8100 ext. 9 ___________________________ Fax 212.876.9421 DATE: ________ DAY: ________ www.elizabar.com # OF PEOPLE: ______ EMAIL CONFIRMATION: __________________________ ITEM AMOUNT QUANTITY Free-Range Roasted Turkey ___14–16 lb. ___22–24 lb. $125/$165 each Whole Boneless Fresh Turkey Breast (approx 3 lb) ___ breast $90 each Rolled & Spit-Roasted Turkey Breast with Herbs approx. ___3 lb. ___6 lb. $90/$180 each Sliced Fresh Turkey Breast ___ lb $45 pound Fresh Turkey Gravy ___ pt $18 pint Giblet Gravy ___ pt $18 pint Whole Roast Capon (Serves 4—6) ___ ea $49 each Orange Glazed Cornish Hen ___ ea $14.95 each Whole Glazed Baked Ham (5 lb. Minimum) ___ lb $30 pound Sliced Glazed Baked Ham ___ lb $30 pound Filet of Beef ___ lb $75 pound Beef Wellington (2 lb. Minimum) ___ lb $75 pound Sliced Brisket of Beef ___ lb $45 pound Brisket Gravy ___ pt $16 pint Herb and Garlic Crusted Leg of Lamb ___ ea $150 each Crown Roast of Pork w/Cornbread and Dried Fruit Stuffing ___ ea $150 each Pumpkin and Butternut Squash Soup ___ qt $18 quart Eli’s Traditional Bread Stuffing ___ lb $14.95 pound Mushroom and Carmelized Onion Stuffing ___ lb $16.95 pound Cornbread Stuffing with Dried Fruit ___ lb $16.95 pound Corn Pudding ___ lb $18.00 pound Fresh Cranberry Sauce ___ pt $14.95 pint Mashed Potatoes ___ pt $16 pint Sweet Potato Purée ___ pt $16 pint Celery Root and Leek Purée ___ pt $14 pint Sage Roasted Beets ___ pt $16 pint Herb Roasted Potatoes ___ pt $14 pint Green Beans and Roasted Garlic ___ -

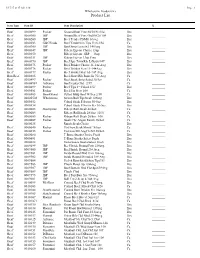

Product List

8/17/17 at 17:14:11.20 Page: 1 Wholesome Foodservice Product List Item Type Item ID Item Description X Beef 0000099 Packer Ground Beef Fine 80/20 Frz10# Lbs. ________ Beef 0000100 IBP Ground Beef Fine Grd 80/20 10# Lbs. ________ Beef 0000200 IBP Beef Tender PSMO 6#avg Lbs. ________ Beef 0000203 G&CFoods Beef Tenderloin Tips Frzn 2/5# Cs. ________ Beef 0000300 IBP Beef Strip Loin 0x1 14#Avg Lbs. ________ Beef 0000349 IBP Ribeye Lip-on Choice 13up Lbs. ________ Beef 0000350 Ribeye Lip-on IBP 13up Lbs. ________ Beef 0000351 IBP Ribeye Lip-on 13up Frzn Lbs. ________ Beef 0000370 IBP Beef Spc Trim(Rib Lifter)6/14# Lbs ________ Beef 0000375 Packer Beef Brisket Choice 11-14# Avg Lbs. ________ Beef 0000376 Packer Beef Brisket Frzn 11-14#Avg Lbs. ________ Beef 0000377 Packer Beef Brisket Flat 65-70# Avg Lbs. ________ Box Beef 0000385 Beef Short Rib Bone-In 75# Avg Cs ________ Beef 0000497 Packer Beef Steak Strip Salad 30/5oz Cs. ________ Beef 00004981 Advance Beef Fajita Ckd 2/5# Cs ________ Beef 0000499 Packer Beef Tips 1" Cubed 2/5# Lbs. ________ Beef 0000501 Packer Beef For Stew 10# Cs. ________ Beef 0000505 Brookwood Pulled BBQ Beef W/Sce 2/5# Cs. ________ Beef 00005502 Wholesome Sirloin Ball Tip Steak 10#avg Lbs ________ Beef 0000552 Cubed Steak F/Swiss 30-5oz Lbs. ________ Beef 0000554 Cubed Steak F/Swiss Frz 30-5oz Lbs. ________ Beef 0000603 Stockyards Ribeye Roll Steak 40/4oz Cs. ________ Beef 0000604 Ribeye RollSteak 28/6oz 10.5# Cs. -

Sufganiyot by Rebekah Maccaby (December, 2020) This Recipe Makes a Square, More Beignet-Like Pastry Than a Jelly Doughnut One Might Get at Dunkin Donuts

Sufganiyot by Rebekah Maccaby (December, 2020) This recipe makes a square, more beignet-like pastry than a jelly doughnut one might get at Dunkin Donuts. After the main recipe is a list of ingredients and extra directions to make a gluten-free version. The dough has very little sugar in it, so by using sugar-free filing, one can make a version suitable for diabetics. The recipe here is dairy, but there are notes on how to make it parve. Ingredients regular half-recipe (works, but ¼ recipe doesn’t) o 2 packets quick-rise yeast (1 packet) o 4 tablespoons sugar (2 tbsp) o ½ c. 2% milk (1/4 c.) (use ½ c. cashew/almond milk for parve*) heated according to directions on yeast o ¼ c. whole wheat pastry flour (2 tbsp.) o 1 ½ c. bleached** all-purpose flour (3/4 c.) o 1 ½ c. white pastry flour (3/4 c.) o ½ c. almond flour (1/4 c.) o ¼ tsp cream of tartar (1/8 tsp) o ½ tsp baking powder (1/4 tsp) o ½ tsp salt (1/4 tsp) o 1 tsp ground cinnamon (1/2 tsp) o 2 tsp vanilla (1 tsp) o 2 whole eggs, separated + 2 whites (1 egg, separated + 1 white) at room temp** ** o 1 tsp apple cider vinegar*** (1/2 tsp) o 4 tablespoons (1/2 stick) butter (2 tbsps.) or pareve margarine, at room temp**** o Fillings (fruit, or icing; see notes) o Powdered Sugar o Vegetable oil for deep-frying (rice bran oil works best—you want a high-temp oil) *soy milk “works,” but has an odd taste. -

T H E O B S E R V

n r The O bserver 1842•1992 Si SOUlCtNTf NNIAL The O bserver Saint MarvS College NOTRE DAME * INDI ANA VOL. XXIV NO. 124 FRIDAY , APRIL 3, 1992 THE INDEPENDENT NEWSPAPER SERVING NOTRE DAME AND SAINT MARY’S Casey: Party Faculty vow to keep must rethink struggling despite veto on abortion Editor's Note: The following isFACULTY PARTICIPATION By BRENDAN QUINN the third of four articles ad dressing the issue of faculty N GOVERNANCE News Writer participation in the academic Part3 of 4 governance of the University. The national Democratic By DAVID KINNEY Party failed to understand the seismic, social, and political News Editor Although the proposal calling shock waves generated by the ■ questions on traditional 1973 Roe vs. Wade decision, for the reorganization of the according to Robert Casey, Academic Council was vetoed, governance/ page 3 governor of Pennsylvania. the debate over faculty partici relationship between students ‘'In the two decades since pation in the academic gover and faculty are handled, then (Roe), the party’s position nance of Notre Dame continues. according to Professor William on abortion went from open to “I haven’t heard anyone say Tageson. closed and from dialogue to they (the faculty) shouldn’t have Professor David O’Connor dictate, and millions of input in the deliberation of said that the governance Democrats headed for those academic issues,” said Dean committee wanted to make a open doors and they never Eileen Kolman of Freshman small, focused, concrete step came back,” Casey said in a Year of Studies. “The question through the proposal, allowing speech yesterday on “The is in the structures.” for more gradual change. -

Studies in Slang, VII

Missouri University of Science and Technology Scholars' Mine Arts, Languages and Philosophy Faculty Research & Creative Works Arts, Languages and Philosophy 01 Jan 2006 Studies in Slang, VII Barry A. Popik Gerald Leonard Cohen Missouri University of Science and Technology, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsmine.mst.edu/artlan_phil_facwork Part of the Arts and Humanities Commons Recommended Citation Popik, B. A., & Cohen, G. L. (2006). Studies in Slang, VII. Rolla, Missouri: Gerald Leonard Cohen. This Book is brought to you for free and open access by Scholars' Mine. It has been accepted for inclusion in Arts, Languages and Philosophy Faculty Research & Creative Works by an authorized administrator of Scholars' Mine. This work is protected by U. S. Copyright Law. Unauthorized use including reproduction for redistribution requires the permission of the copyright holder. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STUDIES IN SLANG, VII Barry A. Popik Independent Scholar 225 East 57 Street, Apt. 7P New York, NY 10022 and Gerald Leonard Cohen Professor of Foreign Languages University of Missouri-Rolla Rolla, Missouri 65409 USA The first six volumes of Studies in Slang appeared in the Forum Anglicum monograph series edited by Otto Hietsch (University of Regensburg). Due to his retirement, Forum Anglicum has been discontinued, although it remains a monument of scholarship and inspiration. 2006 First edition, first printing Published by Gerald Leonard Cohen Department of Arts, Languages, and Philosophy University of Missouri-Rolla Rolla, MO 65409 Copyright © 2006 Gerald Leonard Cohen Rolla, Missouri and Barry A. Popik New York City After printing costs are met, Gerald Cohen will donate his share of any remaining funds to a scholarship fund for liberal arts students at the University of Missouri-Rolla.