25017 Published Article

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Advertiser of the Month

Holden: Editorial ediToRial Australia has a new Commonwealth Minister for Schools, Early Childhood and Youth, Peter Garrett. The newly titled portfolio splits school education and higher education. Prime Minister Julia Gillard announced on 11 Septem- fasT facTs Quick QuiZ ber that Chris Evans would be her Min- Top ranking Australian university in 1. Did Brontosaurus hang out in ister for Jobs, Skills and Workplace Rela- 2010, measured in terms of research swamps because it was too weak to quality and citation counts, graduate carry its own weight since it couldn’t tions. By 14 September, he’d become employability and teaching quality: chew enough food to fuel itself? Minister for Jobs, Skills, Workplace Australian National University at 20th, 2. Who won this year’s Aurecon Bridge Relations and Tertiary Education. down three places from 17th last year. Building Competition? Garrett and Evans will be assisted by Second ranked: University of Sydney at 3. What weight did the winning bridge Jacinta Collins as Parliamentary Secre- 37th, down from equal 36th last year. carry? Third ranked: University of Melbourne at 4. Can you use a school building fund to tary for Education, Employment and 38th, down from equal 36th last year. pay for running expenses? Workplace Relations. Garrett inherits Fourth: University of Queensland at 43rd, 5. Can you offer a scholarship or bur- responsibility for the as-yet unfi nished down from 41st last year. sary to people other than Australian $16.2 billion Building the Education Fifth: University of New South Wales at citizens or permanent residents? 46, up from equal 47th last year. -

“Life on Earth Is at Immediate Risk and Only Implementing the Earth Repair Charter Can Save It”

Join with these Earth Repair Charter endorsers and like and share this Now Age global solution strategy towards helping make the whole world great for everyone. Share earthrepair.net “Life on Earth is at immediate risk and only implementing the Earth Repair Charter can save it”. Richard Jones, Former MLC, Independent, NSW Parliament, Australia “I consider that the Earth Repair Charter is self-evident as an achievable Global Solution Strategy. I urge every national government to adopt it as the priority within each country”. Joanna Macy, PhD , Professor, Teacher, Author, Institute for Deep Ecology, USA “I was thrilled to receive your Earth Repair Charter and all my best wishes are behind it”. David Suzuki, David Suzuki Foundation “The Earth Repair Charter is helping us to be enlightened in our relationship with the Earth and compassionate to all beings”. H.H. The Dalai Lama “The Earth Repair Charter is the way to rescue the future from further ignorance and environmental degradation. Please promote the Charter to help create a safer, healthier and happier world”. Geoffrey BW Little JP, Australia’s Famous, International Smiling Policeman “I am pleased to say that the Earth Repair Charter represents the best possible path for everyone to consider. Best wishes, Good luck”. Peter Garrett, Midnight Oil and Past President of ACF “The Earth Repair Charter has the capacity to galvanise action against the neglect by governments of that which should be most treasured - peace, justice and a healthy planet. I endorse it with great enthusiasm”. Former Senator Lyn Allison, Australian Democrats “The Earth Repair Charter is, in our opinion, a document that can greatly contribute to improving the quality of life on this planet”. -

14 Good Weekend August 15, 2009 He Easy – and Dare I Say It Tempting – Story to Write Translating About Peter Garrett Starts Something Like This

WOLVES 14 Good Weekend August 15, 2009 he easy – and dare i say it tempting – story to write Translating about Peter Garrett starts something like this. “Peter Garrett songs on the was once the bold and radical voice of two generations of Australians and at a crucial juncture in his life decided to pop stage into forsake his principles for political power. Or for political action on the irrelevance. Take your pick.” political stage We all know this story. It’s been doing the rounds for five years now, ever since Garrett agreed to throw in his lot with Labor and para- was never Tchute safely into the Sydney seat of Kingsford Smith. It’s the story, in effect, going to be of Faust, God’s favoured mortal in Goethe’s epic poem, who made his com- easy, but to his pact with the Devil – in this case the Australian Labor Party – so that he might gain ultimate influence on earth. The price, of course – his service to critics, Peter the Devil in the afterlife. Garrett has We’ve read and heard variations on this Faustian theme in newspapers, failed more across dinner tables, in online chat rooms, up-country, outback – everyone, it seems, has had a view on Australia’s federal Minister for the Environment, spectacularly Arts and Heritage, not to mention another song lyric to throw at him for than they ever his alleged hollow pretence. imagined. He’s all “power no passion”, he’s living “on his knees”, he’s “lost his voice”, he’s a “shadow” of the man he once was, he’s “seven feet of pure liability”, David Leser he’s a “galah”, “a warbling twit”, “a dead fish”, and this is his “year of living talks to the hypocritically”. -

![[Warning - This Film Contains Nudity and References to Drugs]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/9259/warning-this-film-contains-nudity-and-references-to-drugs-1069259.webp)

[Warning - This Film Contains Nudity and References to Drugs]

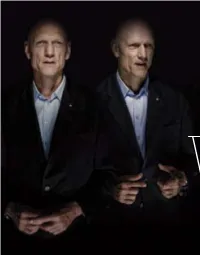

[Warning - This film contains nudity and references to drugs] [What A Life! Rock Photography by Tony Mott - a free exhibition until 7 February 2016. Solid Gold - Jeff Apter & Philip Morris, Metcalfe Theatre, State Library of NSW, 5th December 2015] [Dressed in a black shirt and dark jeans, grey-haired Philip Morris sits beside his interviewer Jess Apter, a bald man dressed casually] [JEFF APTER] Thank you. Before starting, I want to say I was really fortunate to be able to work with Philip on this book. [Jeff Apter holds up a coffee table book] [JEFF APTER] And it was one of the more interesting exercises, wasn't it? Because we were given a directive to come up with... Was it 200 photos? ..for this book. [PHILIP MORRIS] That's right. [JEFF APTER] And Philip's archive is so fantastic and so rich, that I think we got it down to, what, 600? [PHILIP MORRIS] Yeah. [Audience laughs] [JEFF APTER] Was it 600 to start with? It was something like that. And it's staggering, really. It's a really great document of Australian rock history at a really interesting turning point. So to get it down to this... It's begging for a second edition, by the way. There's so many great photos. So it was a real honour to be able to... to do that. It was a lot of fun. [PHILIP MORRIS] Yeah, it was. [JEFF APTER] We actually had built into our contract... Our agreement was an understanding that we would never work in a boring situation. -

Standing Strong for Nature Annual Report 2018–2019 Imagine a World Where Forests, Rivers, People, Oceans and Wildlife Thrive

Standing strong for nature Annual report 2018–2019 Imagine a world where forests, rivers, people, oceans and wildlife thrive. This is the world we can see. This is the world we are creating. Who are we? We are Australia’s national environment organisation. We are more than 600,000 people who speak out, show up and act for a world where all life thrives. We are proudly independent, non-partisan and funded by donations from Australians. Our strategy Change the story Build people Fix the systems power Stories shape what We can’t fix the climate people see as possible. We’re building powerful, and extinction crises one We’re disrupting the old organised communities. spot-fire at a time. That’s story that destruction is Together, we’re holding why we’re taking on big inevitable and seeding decision makers to structural challenges, like new stories that inspire account and pushing for laws, institutions and people to act. real change to create a decisions. better world. Cover. Musk Lorikeet Photo. Annette Ruzicka/MAPgroup Previous page. Karijini National Park. Photo. Bette Devine Contents Message from the President and CEO .......................3 Our impact ..................................................4 Campaign: Stop climate damage ..............................6 Campaign: Stand up for nature ................................12 Campaign: Fix our democracy ................................14 Campaign: Fix our economy ..................................15 Change the story ............................................16 People power ...............................................18 New approaches to our work ................................22 Thank you ...................................................24 Environmental performance ................................34 Social performance and organisational culture .............36 Board and Council ...........................................38 Financial position summary .................................40 We acknowledge the Traditional Owners of this country and their continuing connection to land, waters and community. -

National Press Club Address 24 October 2017 by the Hon Peter Garrett AM

1 National Press Club Address 24 October 2017 by The Hon Peter Garrett AM 'Trashing our crown jewel: The fate of the Great Barrier Reef in the coal age'. I want to begin by acknowledging the traditional custodians of the lands and waters of this area, including the Ngunnawal people. This is my fourth address to the National Press Club, and I thank the club and its sponsors, for this invitation. Now, returning to my first love, music, I'm in town to perform with my colleagues in Midnight Oil on the Australian leg of The Great Circle Tour. On previous visits I've addressed you as ACF President, as a member of parliament, and, later, as a government minister. Amongst other things I've called for environmental tax reform and for the rejuvenation and democratization of the arts. These are still important issues. At some point, hopefully, they will be realised. Still I believe this is the most critical address I have given here. After many years of working both outside and inside the 'system', I'm convinced more than ever that we face an existential threat, greater than any other, as humans literally upend the world's climate and natural ecosystems. To do nothing in the face of this threat, of which we are well aware, is to acquiesce to a world diminishing in front of us. We will deservedly reap the scorn and anger of our children if we fail to act now. There is a fundamental divide in our response. But it is not between insiders and outsiders. -

![[Eu Rev]Csfr4.Qxd](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/9814/eu-rev-csfr4-qxd-1749814.webp)

[Eu Rev]Csfr4.Qxd

ener gy [r]evolution A SUSTAINABLE AUSTRALIA ENERGY OUTLOOK E M I T S M A E R D / S I N N I E M M I © T S M A E R E D / M E I N T S N A M O A J E R © D / E D O O G . B © report australia regional energy scenario introduction 4 executive summary 6 1 policy 9 2 the energy [r]evolution 12 3 energy resources and security of supply 16 4 cost projections 20 5 scenario for a future energy supply 24 6 the australia energy [r]evolution scenario 28 7 policy recommendations 39 appendix 42 Greenpeace International, European Renewable Energy Council (EREC) date June 2008 institute DLR, Institute of Technical Thermodynamics, Department of Systems Analysis and Technology Assessment, Stuttgart, Germany: Dr.Wolfram Krewitt, Dr. Sonja Simon, Dr. Thomas Pregger, Ecofys BV,(Demand Projection), P.O. Box 8408, NL-3503 RK Utrecht, Kanaalweg 16-G, NL-3526 KL Utrecht, The Netherlands: Wina Graus, Eliane Blomen australia scientific reserach Dr Hugh Saddler, Anne Sjostrom; Energy Strategies Pty Ltd., P.O. Box 4170, Level 1, Manuka Arcade, 20 Franklin Street, A.C.T. 2603 Canberra / Australia European Renewable Energy Council (EREC) Arthouros Zervos, Oliver Schäfer employment calculations Jay Rutovitz Greenpeace International Sven Teske Greenpeace Australia Pacific Julien Vincent global project manager Sven Teske, Greenpeace International author Sven Teske, Julien Vincent editor Julien Vincent design & layout Tania Dunster, Jens Christiansen, onehemisphere, Sweden, www.onehemisphere.se contact Greenpeace Australia Pacific: Julien Vincent; [email protected] Greenpeace International: [email protected] EREC: [email protected] for further information about the global, regional and national scenarios please visit the energy [r]evolution website: www.energyblueprint.info/ E M I T GPI REF JN 035. -

THE NATIONAL CURRICULUM and STRATEGIC ADVOCACY for MUSIC and the ARTS Richard Letts, Music Council of Australia September 10, 2009

THE NATIONAL CURRICULUM AND STRATEGIC ADVOCACY FOR MUSIC AND THE ARTS Richard Letts, Music Council of Australia September 10, 2009 There is controversy among some in the music community about the appropriate advocacy objectives for music education, in the context of the formulation of and follow-on from the National Curriculum in the arts. One position says that music is the most valuable of the arts and that our sole objective should be continuous universal school music education for Australian children regardless of competing interests from other art forms, practicalities for governments, the Australian Curriculum Assessment and Reporting Authority (ACARA) or other such considerations. The other position agrees with the objective of universal provision of continuous school music education but says that if it is promoted blindly and regardless of circumstances and competing interests, there may be such dispute and disruption that governments step back and the opportunity for progress is lost. This paper supports and explains the second position. It goes through the history, considers various issues and shows how the strategic position was arrived at. This particular controversy is something of a digression from the real issue, which is as always about resourcing: adequate training of teachers, provision of teaching time, facilities and equipment. GETTING THE ARTS INCLUDED IN THE NATIONAL CURRICULUM 1. In the announcement by the Federal government of the establishment of a national curriculum, the list of subjects omitted the arts. 2. Advice came from high in the bureaucracy that it was essential that the arts seek inclusion because on that would depend the potential for Commonwealth provision of resources for arts education and the knock-on effects for the states. -

The Hon Peter Garrett Mp Media Release

THE HON PETER GARRETT MP Minister for School Education, Early Childhood and Youth MEDIA RELEASE 14 October 2011 First achievement standards for the Australian Curriculum The final achievement standards for the first four subjects in the Australian Curriculum were endorsed today at a joint meeting of Commonwealth, State and Territory Education Ministers. School Education Minister Peter Garrett said the endorsement of the achievement standards was a significant step on the road to a national curriculum. “This means that as the new curriculum in maths, science, English and history is being taught, we will have a common understanding of the quality of student work across the country,” he said. “This is the last piece of the puzzle towards implementing the first phase of the curriculum. We already had the content, now we have the validated standards against which students will be assessed. “Teachers assessing student work in these first four subjects will use the same reference points in Victoria and NSW, for example, as they do in Tasmania and the Northern Territory. “The Australian Curriculum tells teachers what they need to teach and what students are expected to learn. The achievement standards are a guide for teachers about how well the student has understood the content.” Mr Garrett congratulated the Australian Curriculum, Assessment and Reporting Authority (ACARA) for the extensive consultation work it undertook to finalise the achievement standards, allowing states and territories to get on with the job of rolling out the curriculum. $38 million Professional Development Package for Principals Ministers today endorsed a Gillard Government proposal to invest $38 million in a professional development package for school principals, as part of the Quality Teaching National Partnership. -

The Rudd Government Australian Commonwealth Administration 2007–2010

The Rudd Government Australian Commonwealth Administration 2007–2010 The Rudd Government Australian Commonwealth Administration 2007–2010 Edited by Chris Aulich and Mark Evans Published by ANU E Press The Australian National University Canberra ACT 0200, Australia Email: [email protected] This title is also available online at: http://epress.anu.edu.au/rudd_citation.html National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Title: The Rudd government : Australian Commonwealth administration 2007 - 2010 / edited by Chris Aulich and Mark Evans. ISBN: 9781921862069 (pbk.) 9781921862076 (eBook) Notes: Includes bibliographical references. Subjects: Rudd, Kevin, 1957---Political and social views. Australian Labor Party. Public administration--Australia. Australia--Politics and government--2001- Other Authors/Contributors: Aulich, Chris, 1947- Evans, Mark Dr. Dewey Number: 324.29407 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. Cover design by ANU E Press Illustrations by David Pope, The Canberra Times Printed by Griffin Press Funding for this monograph series has been provided by the Australia and New Zealand School of Government Research Program. This edition © 2010 ANU E Press Contents Acknowledgments . vii Contributors . ix Part I. Introduction 1 . It was the best of times; it was the worst of times . 3 Chris Aulich 2 . Issues and agendas for the term . 17 John Wanna Part II. The Institutions of Government 3 . The Australian Public Service: new agendas and reform . 35 John Halligan 4 . Continuity and change in the outer public sector . -

Appendix B – Exhibits

B Appendix B - Exhibits 1 Prof. Peter Newman (Related to Submission No. 3) 2 Australian Institute of Architects Tabled Diagrams 3 Darwin City Council Greenhouse Action Plan 2001-2010 3.1 Prof. Peter Newman and Darwin City Council Costal Erosion Issues in the East Point and Nightcliff of Darwin – Report (Related to Submission No. 3) 4 Property Council of Australia 5 Australian Antarctic Division, Department of the Environment and Heritage Preliminary Tracks from GLS DAT 6 Humane Society International Terrestial Landscapes, Biodiversity and Climate Change (Related to Submission No. 17) 6.1 Humane Society International Garnaut Climate Change Review (Related to Submission No. 17) 6.2 Humane Society International Garnaut Climate Change Review Scheme Discussion Paper March 2008 (Related to Submission No. 17) 100 REPORT 100: TREATIES TABLED ON 25 JUNE 2008 (2) 6.3 Humane Society International Letter to Department of Climate Change regarding National Greenhouse and Energy Reporting System from HIS (Related to Submission No. 17) 6.4 Humane Society International Letter to Hon. Peter Garrett MP and Hon. Penny Wong regarding the Priority areas for carbon (Related to Submission No. 17) 6.5 Humane Society International Letter to Senator Penny Wong from HIS (Related to Submission No. 17) 7 Australian Conservation Foundation CSRIO - Climate Change Impacts on Australia and Benefits of Early Action to Reduce Global Greenhouse Gas Emissions (Related to Submission No. 20) 7.1 Australian Conservation Foundation The Business Case for Early Action (Related to Submission No. 20) 8 Wentworth Group of Concerned Scientists How to include Terrestrial Carbon in Developing Nations in the Overall Climate Change Solution (Related to Submission No. -

Hansard 30 Oct 1997

30 Oct 1997 Vacancy in Senate of Commonwealth of Australia 4051 THURSDAY, 30 OCTOBER 1997 As this Parliament does not have a representative of the Australian Democrats, I move the motion nominating the authorised Australian Democrat nominee and the Leader At 8.45 a.m., of the Opposition seconds the motion. I am very happy to do so, as I am sure my Mr SPEAKER (Hon. N. J. Turner, Nicklin) colleague opposite is happy to second. took the chair. Despite the politics of Cheryl Kernot's precipitate resignation from the Parliament VACANCY IN SENATE OF COMMONWEALTH and the Australian Democrats, it is appropriate OF AUSTRALIA and correct that a spirit of bipartisanship is manifested today in choosing her successor. Nomination of Andrew John Julian Bartlett, vice Cheryl Kernot Today is also an historic occasion because it is the first time to my knowledge Mr SPEAKER: Order! The House has that the Queensland Parliament has fast- resolved to meet at 8.45 a.m. this day for the tracked the selection process by suspending purpose of the election of a senator. There Standing Orders so that the expressed wish of being a quorum present, the meeting is now the Queensland electorate is in no way constituted. Honourable members should note diminished. Honourable members will be that the provisions of Standing Orders and aware that the Government in the House of Rules shall apply to this meeting. I now call for Representatives and the Senate has granted nominations. I point out that every nomination a pair so that, until the Queensland Parliament must be accompanied by a declaration by the fills the vacancy, the relative voting strength of nominee of qualification and consent to be the parties in the Senate is not altered.