Edward Cranswick CC

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Advertiser of the Month

Holden: Editorial ediToRial Australia has a new Commonwealth Minister for Schools, Early Childhood and Youth, Peter Garrett. The newly titled portfolio splits school education and higher education. Prime Minister Julia Gillard announced on 11 Septem- fasT facTs Quick QuiZ ber that Chris Evans would be her Min- Top ranking Australian university in 1. Did Brontosaurus hang out in ister for Jobs, Skills and Workplace Rela- 2010, measured in terms of research swamps because it was too weak to quality and citation counts, graduate carry its own weight since it couldn’t tions. By 14 September, he’d become employability and teaching quality: chew enough food to fuel itself? Minister for Jobs, Skills, Workplace Australian National University at 20th, 2. Who won this year’s Aurecon Bridge Relations and Tertiary Education. down three places from 17th last year. Building Competition? Garrett and Evans will be assisted by Second ranked: University of Sydney at 3. What weight did the winning bridge Jacinta Collins as Parliamentary Secre- 37th, down from equal 36th last year. carry? Third ranked: University of Melbourne at 4. Can you use a school building fund to tary for Education, Employment and 38th, down from equal 36th last year. pay for running expenses? Workplace Relations. Garrett inherits Fourth: University of Queensland at 43rd, 5. Can you offer a scholarship or bur- responsibility for the as-yet unfi nished down from 41st last year. sary to people other than Australian $16.2 billion Building the Education Fifth: University of New South Wales at citizens or permanent residents? 46, up from equal 47th last year. -

“Life on Earth Is at Immediate Risk and Only Implementing the Earth Repair Charter Can Save It”

Join with these Earth Repair Charter endorsers and like and share this Now Age global solution strategy towards helping make the whole world great for everyone. Share earthrepair.net “Life on Earth is at immediate risk and only implementing the Earth Repair Charter can save it”. Richard Jones, Former MLC, Independent, NSW Parliament, Australia “I consider that the Earth Repair Charter is self-evident as an achievable Global Solution Strategy. I urge every national government to adopt it as the priority within each country”. Joanna Macy, PhD , Professor, Teacher, Author, Institute for Deep Ecology, USA “I was thrilled to receive your Earth Repair Charter and all my best wishes are behind it”. David Suzuki, David Suzuki Foundation “The Earth Repair Charter is helping us to be enlightened in our relationship with the Earth and compassionate to all beings”. H.H. The Dalai Lama “The Earth Repair Charter is the way to rescue the future from further ignorance and environmental degradation. Please promote the Charter to help create a safer, healthier and happier world”. Geoffrey BW Little JP, Australia’s Famous, International Smiling Policeman “I am pleased to say that the Earth Repair Charter represents the best possible path for everyone to consider. Best wishes, Good luck”. Peter Garrett, Midnight Oil and Past President of ACF “The Earth Repair Charter has the capacity to galvanise action against the neglect by governments of that which should be most treasured - peace, justice and a healthy planet. I endorse it with great enthusiasm”. Former Senator Lyn Allison, Australian Democrats “The Earth Repair Charter is, in our opinion, a document that can greatly contribute to improving the quality of life on this planet”. -

BHP “Extreme” Consequence Tailings Dams with Potential to Cause Fatality of 100 Employees

BHP “Extreme” consequence tailings dams with potential to cause fatality of 100 employees: Briefing Paper by David Noonan, Independent Environment Campaigner - 22 May 2020 BHP has Questions to answer on Worker Safety, Transparency and Accountability at Olympic Dam BHP took over Olympic Dam copper-uranium mine in 2005, operating the mine for a decade before a GHD “TSF Dam Break Safety Report”1 to BHP in August 2016 concluded all existing Tailings Storage Facilities (TSFs) are “Extreme” consequence tailings dams with a failure potential to cause the death of 100 BHP employees: “BHP OD has assessed the consequence category of the TSFs according to ANCOLD (2012a,b). A dam break study, which considered 16 breach scenarios of TSFs 1 to 5, was completed by GHD (2016) and indicated a potential for tailings and water flow into the mine’s backfill quarry and underground portal. The following conclusions were drawn: • The population at risk (PAR) for a TSF embankment breach is greater than 100 to less than 1000 mine personnel primarily as a result of the potential flow of tailings into the adjacent backfill quarry and entrance to the underground mine. • The financial cost to BHP OD for a tailings dam failure was assessed by BHP OD to be greater than US$1B, a “catastrophic” loss according to ANCOLD guidelines (2012a,b). Based on these criteria, the TSFs at Olympic Dam have been given a consequence category of “Extreme” to guide future assessments and designs. Note that this is an increase compared to the assessment prior to the FY16 Annual Safety Inspection and Review (Golder Associates, 2016a) which classified TSF 1-4 and TSF 5 as “High A” and “High B”, respectively. -

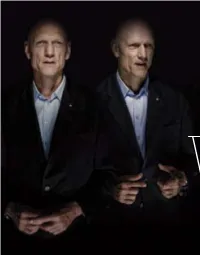

14 Good Weekend August 15, 2009 He Easy – and Dare I Say It Tempting – Story to Write Translating About Peter Garrett Starts Something Like This

WOLVES 14 Good Weekend August 15, 2009 he easy – and dare i say it tempting – story to write Translating about Peter Garrett starts something like this. “Peter Garrett songs on the was once the bold and radical voice of two generations of Australians and at a crucial juncture in his life decided to pop stage into forsake his principles for political power. Or for political action on the irrelevance. Take your pick.” political stage We all know this story. It’s been doing the rounds for five years now, ever since Garrett agreed to throw in his lot with Labor and para- was never Tchute safely into the Sydney seat of Kingsford Smith. It’s the story, in effect, going to be of Faust, God’s favoured mortal in Goethe’s epic poem, who made his com- easy, but to his pact with the Devil – in this case the Australian Labor Party – so that he might gain ultimate influence on earth. The price, of course – his service to critics, Peter the Devil in the afterlife. Garrett has We’ve read and heard variations on this Faustian theme in newspapers, failed more across dinner tables, in online chat rooms, up-country, outback – everyone, it seems, has had a view on Australia’s federal Minister for the Environment, spectacularly Arts and Heritage, not to mention another song lyric to throw at him for than they ever his alleged hollow pretence. imagined. He’s all “power no passion”, he’s living “on his knees”, he’s “lost his voice”, he’s a “shadow” of the man he once was, he’s “seven feet of pure liability”, David Leser he’s a “galah”, “a warbling twit”, “a dead fish”, and this is his “year of living talks to the hypocritically”. -

![[Warning - This Film Contains Nudity and References to Drugs]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/9259/warning-this-film-contains-nudity-and-references-to-drugs-1069259.webp)

[Warning - This Film Contains Nudity and References to Drugs]

[Warning - This film contains nudity and references to drugs] [What A Life! Rock Photography by Tony Mott - a free exhibition until 7 February 2016. Solid Gold - Jeff Apter & Philip Morris, Metcalfe Theatre, State Library of NSW, 5th December 2015] [Dressed in a black shirt and dark jeans, grey-haired Philip Morris sits beside his interviewer Jess Apter, a bald man dressed casually] [JEFF APTER] Thank you. Before starting, I want to say I was really fortunate to be able to work with Philip on this book. [Jeff Apter holds up a coffee table book] [JEFF APTER] And it was one of the more interesting exercises, wasn't it? Because we were given a directive to come up with... Was it 200 photos? ..for this book. [PHILIP MORRIS] That's right. [JEFF APTER] And Philip's archive is so fantastic and so rich, that I think we got it down to, what, 600? [PHILIP MORRIS] Yeah. [Audience laughs] [JEFF APTER] Was it 600 to start with? It was something like that. And it's staggering, really. It's a really great document of Australian rock history at a really interesting turning point. So to get it down to this... It's begging for a second edition, by the way. There's so many great photos. So it was a real honour to be able to... to do that. It was a lot of fun. [PHILIP MORRIS] Yeah, it was. [JEFF APTER] We actually had built into our contract... Our agreement was an understanding that we would never work in a boring situation. -

Standing Strong for Nature Annual Report 2018–2019 Imagine a World Where Forests, Rivers, People, Oceans and Wildlife Thrive

Standing strong for nature Annual report 2018–2019 Imagine a world where forests, rivers, people, oceans and wildlife thrive. This is the world we can see. This is the world we are creating. Who are we? We are Australia’s national environment organisation. We are more than 600,000 people who speak out, show up and act for a world where all life thrives. We are proudly independent, non-partisan and funded by donations from Australians. Our strategy Change the story Build people Fix the systems power Stories shape what We can’t fix the climate people see as possible. We’re building powerful, and extinction crises one We’re disrupting the old organised communities. spot-fire at a time. That’s story that destruction is Together, we’re holding why we’re taking on big inevitable and seeding decision makers to structural challenges, like new stories that inspire account and pushing for laws, institutions and people to act. real change to create a decisions. better world. Cover. Musk Lorikeet Photo. Annette Ruzicka/MAPgroup Previous page. Karijini National Park. Photo. Bette Devine Contents Message from the President and CEO .......................3 Our impact ..................................................4 Campaign: Stop climate damage ..............................6 Campaign: Stand up for nature ................................12 Campaign: Fix our democracy ................................14 Campaign: Fix our economy ..................................15 Change the story ............................................16 People power ...............................................18 New approaches to our work ................................22 Thank you ...................................................24 Environmental performance ................................34 Social performance and organisational culture .............36 Board and Council ...........................................38 Financial position summary .................................40 We acknowledge the Traditional Owners of this country and their continuing connection to land, waters and community. -

Closure Management and Rehabilitation Plan Olympic Dam

CLOSURE MANAGEMENT AND REHABILITATION PLAN OLYMPIC DAM May 2019 Copyright BHP is the sole owner of the intellectual property contained in any documentation bearing its name. All materials including internet pages, documents and online graphics, audio and video, are protected by copyright law. Apart from any fair dealing for the purposes of private study, research, criticism or review as permitted under the provisions of the Copyright Act 1968, no part of this document may be reproduced, transmitted in any form or re-used for any commercial purposes whatsoever without the prior written permission of BHP. This document represents the status of the topic at the date shown and is subject to change without notice. The latest version of this document is available from Document Control. © 2019 BHP. All rights reserved. This document is uncontrolled when printed. This Closure and Rehabilitation Plan has been prepared as information only and is not to be relied on as final or definitive. It would continue to be developed and would be subject to change. BHP Olympic Dam Closure Management and Rehabilitation Plan Closure Management Plan Summary Olympic Dam Mine Project Olympic Dam Document Title Olympic Dam Mine Closure Management and Rehabilitation Plan Document Reference 99232 Mining Tenements Special Mining Lease 1 Company Name BHP Billiton Olympic Dam Corporation Pty Ltd Electronic Approval Record Business Role Name Authors Role Name Principal Strategic Planning Don Grant Principal Environment A&I Murray Tyler Principal Closure Planning Craig Lockhart Reviewer Role Name Manager Closure Planning Rebecca Wright Superintendent Environment, Radiation and Occupational Hygiene James Owen Principal Legal Zoe Jones Approver Role Name Head of Environment Analysis and Improvement Gavin Price Head of Geoscience and Resource Engineering Amanda Weir Asset President Olympic Dam Laura Tyler Document Amendment Record Version. -

Threatening Lives, the Environment and People's Future

other sides to the story Threatening lives, the environment and people’s future An Alternative Annual Report 2010 FRONT COVER: Stockphoto.com INSIDE BACK COVER: BHP Billiton protest. Photo courtesy of the ACE Collective, Friends of the Earth Melbourne. BACK COVER: Mine tailings at the BHP Billiton’s Olympic Dam Mine in South Australia (2008). Photo: Jessie Boylan BELOW: Nickel laterite ore being loaded at Manuran Island, Philipines. The ore is then taken by barge to waiting ships. Credit: CT Case studies questioning BHP Billiton’s record on human rights, transparency and ecological justice CONTENTS Introduction 2 BHP Billiton Shadow Report: Shining a light on revenue flows 3 MOZAMBIQUE: The double standards of BHP Billiton 4 WESTERN SAHARA: Bou Craa phosphate mine 6 PHILIPPINES: BHP Billiton pulls out of Hallmark Nickel 7 CAMBODIA: How “tea-money” got BHP-Billiton into hot water 8 PAPUA NEW GUINEA: Ok Tedi – a legacy of destruction 9 BORNEO: Exploiting mining rights in the Heart of Borneo 11 BHP Billiton Around the World 12 COLOMBIA: Cerrejon Coal mine 14 SOUTH AUSTRALIA: Olympic Dam Mine 16 WESTERN AUSTRALIA: Yeelirrie ‘Wanti - Uranium leave it in the ground’ 18 WESTERN AUSTRALIA: Hero or destroyer 20 NEW SOUTH WALES, AUSTRALIA: Farmers triumph 20 Conclusion 21 Footnotes 23 Credits 24 | 1 | BHP Billiton Alternative Annual Report 2010 This report examines a number of BHP Billiton’s activities must not take place. To date, BHP Billiton has operations around the world. The collection of merely noted that there are “a wide diversity of views” on case studies highlights the disparity between BHP FPIC, and fails to rise to the challenge needed to genuinely Billiton’s ‘Sustainability Framework’ and the reality implement it. -

National Press Club Address 24 October 2017 by the Hon Peter Garrett AM

1 National Press Club Address 24 October 2017 by The Hon Peter Garrett AM 'Trashing our crown jewel: The fate of the Great Barrier Reef in the coal age'. I want to begin by acknowledging the traditional custodians of the lands and waters of this area, including the Ngunnawal people. This is my fourth address to the National Press Club, and I thank the club and its sponsors, for this invitation. Now, returning to my first love, music, I'm in town to perform with my colleagues in Midnight Oil on the Australian leg of The Great Circle Tour. On previous visits I've addressed you as ACF President, as a member of parliament, and, later, as a government minister. Amongst other things I've called for environmental tax reform and for the rejuvenation and democratization of the arts. These are still important issues. At some point, hopefully, they will be realised. Still I believe this is the most critical address I have given here. After many years of working both outside and inside the 'system', I'm convinced more than ever that we face an existential threat, greater than any other, as humans literally upend the world's climate and natural ecosystems. To do nothing in the face of this threat, of which we are well aware, is to acquiesce to a world diminishing in front of us. We will deservedly reap the scorn and anger of our children if we fail to act now. There is a fundamental divide in our response. But it is not between insiders and outsiders. -

BHP Billiton: Dirty Energy

dirty energy Alternative Annual Report 2011 Contents Introduction 1 BHP Global mining operations – dirty energy investments 3 Coal BHP Billiton in Colombia: Destroying communities for coal 4 BHP Billiton in Indonesia: Going for Deadly Coal in Indonesia 7 BHP Billiton in Australia: When too much in!uence is never enough 8 BHP Billiton Australia: Coal mine workers "ght back - Queensland 10 BHP Billiton Australia: BHP battle with farmers - New South Wales 10 Oil and Gas and Greenhouse Gases BHP Billiton globally: Re-carbonising instead of decarbonising 11 BHP Billiton in Australia: Hero or destroyer? 12 Uranium BHP Billiton in Australia: “Wanti” uranium – leave it 13 BHP Billiton in Australia: Irradiating the future 15 BHP Billiton in Indonesia: Mining for REDD a false solution to climate change 18 Solutions? Less mining, more reuse and recycling? 19 Moving into rare earths? 20 Footnotes 22 Introduction “More than 30 million people were displaced in 2010 by environmental and weather-related disasters across Asia, experts have warned, and the problem is only likely to grow worse as cli- mate change exacerbates such problems. Tens of millions more people are likely to be similarly displaced in the future by the effects of climate change, including rising sea levels, floods, droughts and reduced agricultural productivity. Such people are likely to migrate in regions across Asia, and governments must start to prepare for the problems this will create.” – Asian Development Bank Report1 %+3 %LOOLWRQ LV WKH ZRUOG¶V ODUJHVW GLYHUVL¿HG QDWXUDO SROLF\ -

Olympic Dam Expansion

OLYMPIC DAM EXPANSION DRAFT ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACT STATEMENT 2009 APPENDIX P CULTURAL HERITAGE ISBN 978-0-9806218-0-8 (set) ISBN 978-0-9806218-4-6 (appendices) APPENDIX P CULTURAL HERITAGE APPENDIX P1 Aboriginal cultural heritage Table P1 Aboriginal Cultural Heritage reports held by BHP Billiton AUTHOR DATE TITLE Antakirinja Incorporated Undated – circa Report to Roxby Management Services by Antakirinja Incorporated on August 1985 Matters Related To Aboriginal Interests in The Project Area at Olympic Dam Anthropos Australis February 1996 The Report of an Aboriginal Ethnographic Field Survey of Proposed Works at Olympic Dam Operations, Roxby Downs, South Australia Anthropos Australis April 1996 The Report of an Aboriginal Archaeological Field Survey of Proposed Works at Olympic Dam Operations, Roxby Downs, South Australia Anthropos Australis May 1996 Final Preliminary Advice on an Archaeological Survey of Roxby Downs Town, Eastern and Southern Subdivision, for Olympic Dam Operations, Western Mining Corporation Limited, South Australia Archae-Aus Pty Ltd July 1996 The Report of an Archaeological Field Inspection of Proposed Works Areas within Olympic Dam Operations’ Mining Lease, Roxby Downs, South Australia Archae-Aus Pty Ltd October 1996 The Report of an Aboriginal Heritage Assessment of Proposed Works Areas at Olympic Dam Operations’ Mining Lease and Village Site, Roxby Downs, South Australia (Volumes 1-2) Archae-Aus Pty Ltd April 1997 A Report of the Detailed Re-Recording of Selected Archaeological Sites within the Olympic Dam Special -

Public Submission to BHP's EPBC Act Referral 2019/8570 “Olympic Dam

Public Submission to BHP’s EPBC Act Referral 2019/8570 “Olympic Dam Resource Development Strategy” copper-uranium mine expansion 9th December 2019 The proposed BHP “Olympic Dam Resource Development Strategy” (OD-RDS) copper-uranium mine expansion, and BHP’s proposed major new Tailings Storage Facility 6 (TSF 6) Referral 2019/8465 and associated Evaporation Pond 6 (EP 6) Referral 2019/8526, present significant environmental and public health implications. In particular, in relation to protection of Matters of National Environmental Significance (NES), to mine water consumption with impacts on the Great Artesian Basin and on the unique and fragile Mound Springs, and to radioactive risks and impacts. Uranium mining at BHP’s Olympic Dam mine is a controlled “nuclear action” and “Matter of National Environmental Significance” under the federal Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 (EPBC Act): “this means that it is necessary to consider impacts on the whole environment” (federal Department of Environment, Sept 2011, p.4). Our organisations, ACF, FoE Australia and Conservation SA, welcome this opportunity to comment and draw your attention to the following over-arching recommendations in relation to your consideration of BHP’s applications. • The Olympic Dam operation should be assessed in its entirety in an Environmental Impact Statement (EIS) level public assessment process under the EPBC Act, with the full range of project impacts subject to public consultation. • A comprehensive Safety Risk Assessment of all Olympic Dam mine tailings and tailings storage facilities is required as part of this EPBC Act EIS level public process. This is particularly important given the identification by BHP of three ‘extreme-risk’ status tailings facilities at Olympic Dam.