Realization and Suppression of Situationism

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cosmonauts of the Future: Texts from the Situationist

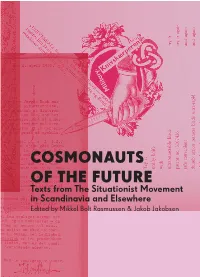

COSMONAUTS OF THE FUTURE Texts from The Situationist Movement in Scandinavia and Elsewhere Edited by Mikkel Bolt Rasmussen & Jakob Jakobsen 1 COSMONAUTS OF THE FUTURE 2 COSMONAUTS OF THE FUTURE Texts from the Situationist Movement in Scandinavia and Elsewhere 3 COSMONAUTS OF THE FUTURE TEXTS FROM THE SITUATIONIST MOVEMENT IN SCANDINAVIA AND ELSEWHERE Edited by Mikkel Bolt Rasmussen & Jakob Jakobsen COSMONAUTS OF THE FUTURE Published 2015 by Nebula in association with Autonomedia Nebula Autonomedia TEXTS FROM THE SITUATIONIST Læssøegade 3,4 PO Box 568, Williamsburgh Station DK-2200 Copenhagen Brooklyn, NY 11211-0568 Denmark USA MOVEMENT IN SCANDINAVIA www.nebulabooks.dk www.autonomedia.org [email protected] [email protected] AND ELSEWHERE Tel/Fax: 718-963-2603 ISBN 978-87-993651-8-0 ISBN 978-1-57027-304-9 Edited by Editors: Mikkel Bolt Rasmussen & Jakob Jakobsen | Translators: Peter Shield, James Manley, Anja Büchele, Matthew Hyland, Fabian Tompsett, Jakob Jakobsen | Copyeditor: Marina Mikkel Bolt Rasmussen Vishmidt | Proofreading: Danny Hayward | Design: Åse Eg |Printed by: Naryana Press in 1,200 copies & Jakob Jakobsen Thanks to: Jacqueline de Jong, Lis Zwick, Ulla Borchenius, Fabian Tompsett, Howard Slater, Peter Shield, James Manley, Anja Büchele, Matthew Hyland, Danny Hayward, Marina Vishmidt, Stevphen Shukaitis, Jim Fleming, Mathias Kokholm, Lukas Haberkorn, Keith Towndrow, Åse Eg and Infopool (www.scansitu.antipool.org.uk) All texts by Jorn are © Donation Jorn, Silkeborg Asger Jorn: “Luck and Change”, “The Natural Order” and “Value and Economy”. Reprinted by permission of the publishers from The Natural Order and Other Texts translated by Peter Shield (Farnham: Ashgate, 2002), pp. 9-46, 121-146, 235-245, 248-263. -

Détournement

Defacement, curated by Amanda accompany the exhibition, Defacement Schmitt July 14 - August 31, 2018 Location: The Club L u c a s GINZA SIX Ajemian 6F, 6-10-1 Richard Ginza Aldrich Chuo-ku, Maria Tokyo, Eichhorn Japan Brook Hsu Susan Howe Dates: N i c o l a s 2018, July Guagnini 15 Jacqueline de Jong Leigh Ledare Artists: RH Quaytman Stan Brakhage Gerhard Richter Aleksandra Domanovic Betty Tompkins Storm de Hirsch Andy Warhol Isidore Isou Video Screening: Gordon Matta-Clark A video Pilvi Takala screening Naomi to Uman INTRODUCTION In 1961, Asger Jorn and Jacqueline de Jong (artists and original members of the Situationist I n t e r n a t i o n a l ) b e g a n working on a multi-volume publication of photographic picture books called the Institute for Comparative Vandalism which aimed to understand how the evolving defacement of Northern European c u l t u r a l o b j e c t s a n d edifices could alter and supersede the meaning of the artifacts that were vandalized (per se). The Institute was focused on illustrating how this vandalism was driven by aesthetic, artistic forces without any concrete reasons: an artistic vandalism without political, violent, dictatorial or r e v o l u t i o n a r y motivations. In Jorn's purview, this concept is aligned w i t h t h e c l a s s i c situationist strategy of détournement, the “integration of p r e s e n t o r p a s t artistic production i n t o a s u p e r i o r construction of a milieu,”1 and was further explored in the publication The Situationist Times (published and edited by de Jong from 1962-67). -

The Sex of the Situationist International*

The Sex of the Situationist International* KELLY BAUM Today the fight for life, the fight for Eros, is the political fight. —Herbert Marcuse, Eros and Civilization In June 1958, Guy Debord, Gil Wolman, Michèle Bernstein, and other found- ing members of the Situationist International (SI) published the first issue of internationale situationniste (IS). There, interspersed among essays on police brutal- ity, functionalist architecture, and industrialization—essays all invested with a clear sense of import and urgency—are found photographs of sexy, flirtatious women. One stands underneath a shower, smiling as water trickles down her neck, while another wears nothing but a man’s trench coat, an erotic accouterment through which she exposes a thigh and a tantalizing glimpse of décolletage. What are sexually charged images such as these doing in a periodical whose twelve issues published some of the most incisive critiques of alienation, capitalism, and spectacle—along with astute analyses of current events like the Franco-Algerian War and the Watts Riots—to appear after World War II? Readymade photographs of nude and semi-nude women are one of the leitmotifs of Situationist visual production. They embellish everything, from its collages and artist books to its films and publications. Nevertheless, these images have received only cursory attention from historians, and in the opin- ion of those who have addressed them, they constitute little more than a gratuitous sidebar to the group’s more lofty, less compromised pursuits. Susan Suleiman’s view, expressed in a footnote to her 1990 book Subversive Intent, typi- fies the scholarly response to date. “The Situationists appear to have been more of a ‘men’s club’ than the Surrealists,” Suleiman writes. -

Constructed Situations: a New History of the Situationist International

ConstruCted situations Stracey T02909 00 pre 1 02/09/2014 11:39 Marxism and Culture Series Editors: Professor Esther Leslie, Birkbeck, University of London Professor Michael Wayne, Brunel University Red Planets: Marxism and Science Fiction Edited by Mark Bould and China Miéville Marxism and the History of Art: From William Morris to the New Left Edited by Andrew Hemingway Magical Marxism: Subversive Politics and the Imagination Andy Merrifield Philosophizing the Everyday: The Philosophy of Praxis and the Fate of Cultural Studies John Roberts Dark Matter: Art and Politics in the Age of Enterprise Culture Gregory Sholette Fredric Jameson: The Project of Dialectical Criticism Robert T. Tally Jr. Marxism and Media Studies: Key Concepts and Contemporary Trends Mike Wayne Stracey T02909 00 pre 2 02/09/2014 11:39 ConstruCted situations A New History of the Situationist International Frances Stracey Stracey T02909 00 pre 3 02/09/2014 11:39 For Peanut First published 2014 by Pluto Press 345 Archway Road, London N6 5AA www.plutobooks.com Copyright © the Estate of Frances Stracey 2014 British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library ISBN 978 0 7453 3527 8 Hardback ISBN 978 0 7453 3526 1 Paperback ISBN 978 1 7837 1223 6 PDF eBook ISBN 978 1 7837 1225 0 Kindle eBook ISBN 978 1 7837 1224 3 EPUB eBook Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data applied for This book is printed on paper suitable for recycling and made from fully managed and sustained forest sources. Logging, pulping and manufacturing processes are expected to conform to the environmental standards of the country of origin. -

Scandinavian Institute for Comparative Vandalism in Silkeborg, Denmark

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by St Andrews Research Repository Niels Henriksen – Asger Jorn Article 5, Inferno Volume VIII, 2003 1 Asger Jorn and the Photographic Essay on Scandinavian Vandalism Niels Henriksen n the last few years the Danish painter, potter and sculptor Asger Jorn (1914-1973) has had a revival. He has been the subject of several publications and large exhibitions at The National Museum in ICopenhagen and Arken Museum of Modern Art, Copenhagen. Although Asger Jorn is sometimes presented as the Scandinavian exponent of post war Abstract Expressionism, he was really a movement of his own, consciously working against such categorisations, and arguing against abstraction in art. The artistic practices of Jorn are perhaps so defiant of categorisation because they rely on and exist in constant dialogue with a quite original theoretical framework, which evolved with the artist throughout his life. From the beginning of the 1940s onwards Jorn was the initiator of periodicals and movements and always an ardent supplier of manifestos and articles. The best known of these movements are the COBRA-group and the Situationist International. The Situationist movement has, like Jorn, although rather independently of him, recently received a revival or interest, especially in the fields of architecture and urban planning, but also in literature and art. The first SI (Situationist International) was held 1957 at Cosio d’Arroscia in Italy, with participation of the LPC (London Psychogeographic Committee), LI (Lettrist International), the LPI (Potlatch LI) and IMBI (International Movement for an Imaginist Bauhaus). -

MAMCO DP 27Fev 2018 UK 1

M�M�M�M�M� M�M�M�M�M�M� �M �M �M �M �M �M �M M� �M �M �M �M �M �M �M �M �M �M �M �M �M �M �M �M Die Welt als Labyrinth Art & Entertainment New Images Opening : Tuesday February 27 2018 – 6pm 10, rue des Vieux-Grenadiers, 1205 Geneva � � � � � � � p. 3 Press Release Die Welt als Labyrinth (3rd floor) p. 5 Introduction p. 6 Gil Joseph Wolman p. 8 Letterism and the letterist International p. 9 ”Cavern of Antimatter” / Modifications p. 11 SPUR / Situationist Times p. 12 Destruction of the RSG-6 p. 15 Ralph Rumney p.16 Movement for an imaginist Bauhaus Alba’s experimental laboratory p.18 Art & Entertainment (2nd floor) p. 20 New Images (1st floor) Other Exhibition p. 22 A Collection of Spaces p.24 L’ Appartement p.26 Informations and Partners M�M�M�M�M� M�M�M�M�M�M� �M �M �M �M �M �M �M �M �M �M �M �M �M �M �M �M �M � � � � � � � � � � � � � Die Welt als Labyrinth Art & Entertainment Nouvelles images Opening : Tuesday February 27 2018 – 6pm 10, rue des Vieux-Grenadiers, 1205 Geneva Press Conference Tuesday February 27 2018 – 11am This spring, MAMCO has decided to turn aimed at art criticism (Piet de Groof’s action back to Letterism and the Situationist Inter- with Debord and Wyckaert against the gene- national, two artistic movements from Paris ral assembly of the AICA in Brussels), art mar- which occupied a very special place on the ket galleries (Jorn’s and Gallizio’s shows political horizon of May 1968. -

Scandinavian Institute for Comparative Vandalism in Silkeborg, Denmark

Niels Henriksen – Asger Jorn Article 5, Inferno Volume VIII, 2003 1 Asger Jorn and the Photographic Essay on Scandinavian Vandalism Niels Henriksen n the last few years the Danish painter, potter and sculptor Asger Jorn (1914-1973) has had a revival. He has been the subject of several publications and large exhibitions at The National Museum in ICopenhagen and Arken Museum of Modern Art, Copenhagen. Although Asger Jorn is sometimes presented as the Scandinavian exponent of post war Abstract Expressionism, he was really a movement of his own, consciously working against such categorisations, and arguing against abstraction in art. The artistic practices of Jorn are perhaps so defiant of categorisation because they rely on and exist in constant dialogue with a quite original theoretical framework, which evolved with the artist throughout his life. From the beginning of the 1940s onwards Jorn was the initiator of periodicals and movements and always an ardent supplier of manifestos and articles. The best known of these movements are the COBRA-group and the Situationist International. The Situationist movement has, like Jorn, although rather independently of him, recently received a revival or interest, especially in the fields of architecture and urban planning, but also in literature and art. The first SI (Situationist International) was held 1957 at Cosio d’Arroscia in Italy, with participation of the LPC (London Psychogeographic Committee), LI (Lettrist International), the LPI (Potlatch LI) and IMBI (International Movement for an Imaginist Bauhaus). Central to the Situationist movement was a defiance of the “spectacle”, the capitalist creation of artificial dreams and desires, and the realisation of every person as an artist. -

Jacqueline De Jong Resilience(S) 28 November

Jacqueline de Jong Resilience(s) 28 November 2019 - 18 January 2020 Pippy Houldsworth Gallery is delighted to present Resilience(s), Jacqueline de Jong’s first solo exhibition in the UK, running from 28 November 2019 to 18 January 2020. The exhibition will focus on paintings made in the 1980s and early 1990s, bringing together key works from her Upstairs Downstairs and Paysages Dramatiques series. Exuberant, sensual, violent and contradictory, Resilience(s) manifests the defiance and adaptability inherent in de Jong’s practice. Towards the middle of the 1980s de Jong began to return to a more expressionist style of painting, her work having become increasingly figurative in the 1970s. Here the grotesque figures from her 1960s paintings make a reappearance with a more overtly animal form. The Upstairs Downstairs series, originally commissioned for the Amsterdam Town Hall, places its protagonists in the liminal space of the stairwell, ascending and descending, seemingly without purpose. In contrast, the paintings of the Paysages Dramatiques series draw upon a trip de Jong made to the Dutch island of Schiermonnikoog depicting its characters against an apocalyptic landscape of twisted trees and swirling waters. Certain of the Paysages Dramatiques dispense with figures, leaving the same unbridled emotions to be expressed through the colour and form of the landscape alone. Clashing with one another, de Jong’s creatures are driven by violent and carnal lusts. In Ceux qui vont en bateau (1987), bestial creatures collide in passionate embrace as the simian visage of one sucks in the other and a human figure looks on grinning, its face distorted into a fanged mask. -

1 Defacement, Curated by Amanda Schmitt

1 Defacement, curated by Amanda Schmitt INTRODUCTION In 1961, Asger Jorn and Jacqueline de Jong (artists and original members of the Situationist International) began working on a multi-volume publication of photographic picture books called the Institute for Comparative Vandalism which aimed to understand how the evolving defacement of Northern European cultural objects and edifices could alter and supersede the meaning of the artifacts that were vandalized (per se). The Institute was focused on illustrating how this vandalism was driven by aesthetic, artistic forces without any concrete reasons: an artistic vandalism without political, violent, dictatorial or revolutionary motivations. In Jorn's purview, this concept is aligned with the classic situationist strategy of détournement, the “integration of present or past artistic production into a superior construction of a milieu,”1 and was further explored in the publication The Situationist Times (published and edited by de Jong from 1962-67). In Jorn’s own words, "Détournement is a game made possible by the capacity of devaluation. Only he who is able to devalorize can create new values...It is up to us to devalorize or to be devalorized according to our ability to reinvest in our own culture.”2 In short, one must sacrifice the past to make way for the future. Détournement is closely related to defacement –as illustrated in this exhibition-- in which both the source and the meaning of the original subject or object are subverted to create a new work. The artworks in Defacement thus fulfill Jorn’s premise of vandalism and the collective situationist notion of détournement, while also investigating the concept as explored by anthropologist Michael Taussig in his eponymous book, asking what surfaces when an artist defaces the surface? One of the most notorious examples of defacement is illustrated in Guy Debord’s graffito, “Ne Travaillez Jamais,” scrawled on a public embankment in Paris in 1963. -

The Situationist Avant-Garde Book Fin De Copenhague

FULL AUTOMATION IN ITS INFANCY: THE SITUATIONIST AVANT-GARDE BOOK FIN DE COPENHAGUE Dominique Routhier ABSTRACT This article discusses Fin de Copenhague, a Situationist book experiment from 1957 by Asger Jorn and Guy Debord. By way of a contextualizing archival study with special attention to Jorn’s contemporaneous book project Pour la forme, the article demonstrates that the Russian avant-garde book was a key influence if also a point of critical departure. On this reading, Fin de Copenhague marks a turn away from the unbridled technological optimism of the historical avant-garde. In its material implications and aesthetic choices, Fin de Copenhague draws attention to crucial changes in the capitalist mode of production and challenges the then nascent discourse about “full automation.” KEYWORDS Postwar, Automation, the Situationist International, Asger Jorn, Guy Debord, Value-form theory. The Nordic Journal of Aesthetics, No. 60 (2020), pp. 48–71 48 “What do you want? Better and cheaper food? Lots of new clothes? A dream home with all the latest comforts and labour-saving devices? A new car … a motor-launch … a light aircraft of your own ?,” asks an anonymous British ad, that, somehow, found its way into the chaotic jumble of cut-out materials making up Fin de Copenhague: a joint artistic enterprise that Asger Jorn and Guy Debord undertook in May 1957. (Fig. 1) Clippings from various newspapers, illustrated weeklies, advertisement catalogs, women’s magazines, and other commercial debris from the booming postwar economy’s dizzying new visual battle array form the bulk of this paint-stained, thirty- something pages of “montage wrapped in flong.”1 In a seamless glide from the necessities in life (“better and cheaper food”) to propositions about the wildest eccentricities imaginable (“a light aircraft your own”!), the British ad builds up an imaginary world that it promises to deliver in the twinkling of an eye: Whatever you want, it’s coming your way—plus greater leisure for enjoying it all. -

The Situation of the Situationists: a Cultural Left in France in the 1950S and 60S

The Situation of the Situationists: A Cultural Left in France in the 1950s and 60s MOST OF US, if we know anything at all about the Situationist International, know Guy Debord’s brilliant and famous pamphlet The Society of the Spectacle and, if we are old enough, perhaps remember the striking cover of its English language edition showing rows of moviegoers sitting passively and expectantly in a theater wearing 3-D glasses. Debord and the Situationists made their big splash with that pamphlet which was published in France in 1968 just in time to inspire young people with its powerful anti-commodity and anti-capitalist message. Society, said Debord, had been emptied of all life, reducing us to an audience of contrived spectacles, the consumers of vapid commodities, the incarnation of alienation. Some have credited Debord and his Situationist co-thinkers with having inspired the student movement which in turn detonated the national strike that brought France to a standstill and shook the foundations of President Charles De Gaulle’s government in 1968. While Debord wrote a remarkable pamphlet and the Situationists offered a fascinating critique of contemporary capitalist society, crediting them with being the catalysts of France’s May-June 1968 events would be going too far. Mostly they were an interesting group of Bohemian intellectuals on the left who happened to be in the right place at the right time for one remarkable moment. McKenzie Wark, a teacher at the New School for Social Research and Eugene Lang College, makes no extravagant claims for the Situationists’ role in modern history, though he does argue that the group’s ideas about art and architecture, about geography and city planning, about modern cities and capitalism, and about everyday life and revolutionary change remain meaningful. -

Jacqueline De Jong Et the Situationist Times

SAME PLAYERS SHOOT AGAIN : JACQUELINE DE JONG ET THE SITUATIONIST TIMES 12 décembre 2020 - 23 janvier 2021 TREIZE, 24 rue Moret, 75011 Paris Le 18 septembre 2016, lors d’une visite au Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) de Boston, la peintre néerlandaise Jacqueline de Jong (née en 1939) tombe sur le Digi-Comp II, un jouet éducatif présentant les rudiments de la logique computationnelle à l’aide de boules, d’un plan incliné et de déviateurs. Cette rencontre fortuite lui rappelle le souvenir d’une passion de jeunesse pour une autre machine, autrement plus ludique : le flipper. Au début des années 1970, l’artiste avait en effet entrepris de consacrer à ce jeu le septième numéro de sa revue The Situationist Times. Conçu avec le designer et galeriste Hans Brinkmann, ce Pinball issue n’a finalement pas vu le jour. Il en reste un ensemble de documents préparatoires – photographies, correspondance, coupures de presse, imprimés divers –, jusque là conservés dans un carton, oublié dans la maison d’Amsterdam de l’artiste. Ces archives sont au cœur du projet éditorial et curatorial “These Are Situationist Times”, mené par le chercheur norvégien Ellef Prestæter et Torpedo Press (Oslo) en étroite collaboration avec Jacqueline de Jong. Elles rejoindront bientôt le reste du fonds Jacqueline de Jong de la Beinecke Library à l’université de Yale. “Same Players Shoot Again” constitue l’adaptation parisienne d’une exposition qui, depuis 2018, a connu plusieurs étapes et met à l’honneur le livre et l’interface numérique, élaborés avec Torpedo Press et l’Institute for Computational Vandalism.