Mutating Marks: Refusing to Lose the Trademark Trail Robert W

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

What Is Sport? Pdf, Epub, Ebook

WHAT IS SPORT? PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Roland Barthes | 80 pages | 20 Nov 2007 | Yale University Press | 9780300116045 | English | New Haven, CT, United States What Is Sport? PDF Book Throughout her career, she has won 90 international tournaments — the most wins for any female golfer. Some padded sports bras can feel bulky and uncomfortable, but the Padded Strappy Sports Bra is an exception to the rule. Once expensive luxuries, these cameras now come in many price points, putting them in financial reach of virtually every outdoor enthusiast. In honor of Biles achievements, two gymnastic moves were named after her. That the feats of the Cretans may have been both sport and ritual is suggested by evidence from Greece, where sports had a cultural significance unequaled anywhere else before the rise of modern sports. Schedules are also available by clicking on any team within the scoreboard to see the team's page, including the current season's schedule. I nflated Egos. Scroll down halfway and on the right-hand side you'll see a section to click on Schedule to see the current schedule. She was one of the original faces of ESPN, and there was a time when you could watch one of her shows at almost any time of day. In all probability, polo evolved from a far rougher game played by the nomads of Afghanistan and Central Asia. Article Contents. Despite the clarity of the definition, difficult questions arise. The performance rests on your shoulders, and you receive all of the credit for your victory. Considering the extreme success of the show she hosts alongside Stephen A. -

Tony Kornheiser Returns to XM Satellite Radio

NEWS RELEASE Tony Kornheiser Returns to XM Satellite Radio 1/10/2008 WASHINGTON, Jan. 10 /PRNewswire-FirstCall/ -- Tony Kornheiser will return to XM Satellite Radio on January 21 on the sports talk radio channel XM Sports Nation. (Logo: http://www.newscom.com/cgi-bin/prnh/20070313/XMLOGO ) "The Tony Kornheiser Show" will air nationwide on XM Sports Nation (XM Channel 144) weekdays from 8:15 a.m. to 10 a.m. ET. Kornheiser is returning to the radio airwaves after a seven-month hiatus to focus on his role as analyst for ESPN's "Monday Night Football." "The Tony Kornheiser Show" originates from Washington, D.C. on the local radio station 3WT AM/FM. The show is carried nationwide on XM. XM is the only national broadcaster to air the program. January 21 will mark Kornheiser's first day back on the air at both XM and 3WT. Tony Kornheiser has hosted local and national radio programs for 14 years. The Washington Post columnist is the co-host of ESPN's "Pardon the Interruption," and is currently in his second season as an analyst on "Monday Night Football." "I'm thrilled to be back on the radio," Kornheiser said. "The national audience that watches 'PTI' and 'Monday Night Football' and reads the columns in the Post can now listen to our show every weekday morning on XM Sports Nation." "Tony's back, and we're proud to be bringing him to millions of listeners across the country," said Kevin Straley, XM 1 senior vice president of news, sports, and talk programming. -

ESPN's NFC East Blog Quit Last Week, He Has Lost Ever Ounce of Respect from the Fans and His Competition

IN THE SUPERIOR COURT OF THE DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA CIVIL DIVISION DANIEL M. SNYDER, Plaintiff, Civil Action No. 2011 CA 003168 B Judge Todd E. Edelman v. Next court date: July 29, 2011 CREATIVE LOAFING, INC., CL Event: Initial scheduling conference WASHINGTON, INC. (d/b/a WASHINGTON CITY PAPER); and DAVE MCKENNA, Defendants. PRAECIPE FOR CONTINUATION OF SPECIAL MOTION TO DISMISS THE COMPLAINT: EXHIBITS 101150 TO AFFIDAVIT OF ALIA L. SMITH, ESQ. Due to size restrictions, Defendants have had to submit multiple filings. Please consider this a continuation of Defendants’ Special Motion to Dismiss the Complaint. Dated: June 17, 2011 Respectfully submitted, BAKER & HOSTETLER, L.L.P. LEVINE SULLIVAN KOCH & SCHULZ, L.L.P. By: /s/ Bruce D. Brown By: /s/ Jay Ward Brown Bruce D. Brown (D.C. Bar No. 457317) Seth D. Berlin (D.C. Bar No. 433611) Mark I. Bailen (D.C. Bar No. 459623) Jay Ward Brown (D.C. Bar No. 437686) Washington Square, Suite 1100 Alia L. Smith (D.C. Bar No. 992629) 1050 Connecticut Avenue, N.W. 1050 Seventeenth Street, N.W., Suite 800 Washington, DC 200365304 Washington, D.C. 20036 Telephone: (202) 8611660 Telephone: (202) 5081100 Facsimile: (202) 8611783 Facsimile: (202) 8619888 [email protected]; [email protected]; [email protected], [email protected] [email protected] Counsel for Defendant Dave McKenna David M. Snyder (pro hac vice pending) DAVID M. SNYDER, P.A. 1810 S. MacDill Avenue, Suite 4 Tampa, FL 336295960 Telephone: (813) 2584501 Facsimile: (813) 2584402 [email protected] Counsel for Defendant CL Washington, Inc. -

APS and AIP Initiate Inside Science News Service

A P S N E W S OCTOBER 1999 THE AMERICAN PHYSICAL SOCIETY VOLUME 8, NO. 9 [Try the enhanced APS News-online: http://www.aps.org/apsnews] APSCelebrate News APS a Century 100 of years Physics APS and AIP Initiate Inside Science News Service he American Physical Society has lottery than this happening.” We re- Tteamed with the American Institute leased a tongue-in-cheek explanation of Physics to create Inside Science of why he was way off (with all due News Service, a new resource for respect, he had a much better chance • Fun things parents can do with journalists that will make it easier for of pitching a perfect game). children to teach science over them to uncover, understand, and the summer on ABC’s Good • US Physics Olympiad Team’s ex- explain important science that adds Morning America. ABC News.com cellent third-place finish in the depth to news stories. Inside Science linked to the APS webpage Play- worldwide competition was placed in News Service offers resources and ground Physics [www.aps.org/ the following newspapers: USA Today, fingertip access to thousands of playground.html] experts in all fields of science, free-of- Dallas Morning News, The Denver charge. Randy Atkins, the APS Senior Post, Denver Rocky Mountain News, Media Relations Coordinator, asks for and The Record-Journal (Hartford, members help in getting coverage in CT). [See IN BRIEF, page 3] the popular press by alerting him of new and noteworthy scientific • Why power outages occur dur- advances. Randy can be reached at ing heat waves explanation with 301-209-3238 or via email at APS member quotes was used in a [email protected]. -

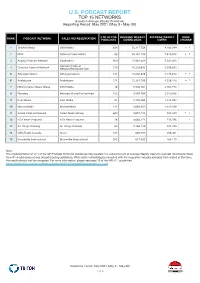

U.S. PODCAST REPORT TOP 15 NETWORKS Based on Average Weekly Downloads Reporting Period: May 2021 (May 3 - May 30)

U.S. PODCAST REPORT TOP 15 NETWORKS Based on Average Weekly Downloads Reporting Period: May 2021 (May 3 - May 30) # OF ACTIVE AVERAGE WEEKLY AVERAGE WEEKLY RANK RANK PODCAST NETWORK SALES REPRESENTATION PODCASTS DOWNLOADS USERS CHANGE 1 Stitcher Media SXM Media 459 35,317,758 9,163,399 1 2 NPR National Public Media 55 35,162,199 7,425,526 1 3 Audacy Podcast Network Cadence13 500 17,982,442 5,542,005 Cumulus Podcast 4 Cumulus Podcast Network Network/Westwood One 270 15,225,592 3,556,832 5 AdLarge/cabana AdLarge/cabana 134 13,050,876 4,173,613 1 6 Audioboom Audioboom 274 12,281,759 4,326,418 1 7 NBCUniversal News Group SXM Media 46 9,926,761 2,764,770 8 Wondery Wondery Brand Partnerships 102 9,589,764 2,910,636 9 Kast Media Kast Media 93 3,795,469 1,514,087 10 WarnerMedia WarnerMedia 114 3,698,251 1,437,168 11 Salem Podcast Network Salem Media Group 662 2,691,743 534,539 1 12 FOX News Podcasts FOX News Podcasts 48 2,665,171 735,796 1 13 All Things Comedy All Things Comedy 52 2,166,142 944,325 14 CBC/Radio-Canada Acast 333 685,707 236,461 15 Bonneville International Bonneville International 252 647,352 184,170 Note: The implementation of v2.1 of the IAB Podcast Technical Guidelines has resulted in a reduced count of Average Weekly Users for podcast downloads made from IP v6 addresses across all participating publishers. While both methodologies complied with the respective industry standard that existed at that time, the results should not be compared. -

2001 Annual Report

wdwCovers 12/18/01 5:17 PM Page 1 The Company ANNUAL REPORT 2001 wdwCovers 12/18/01 5:17 PM Page 2 Reveta F. Bowers John E. Bryson Roy E. Disney Michael D. Eisner Judith L. Estrin Stanley P. Gold Robert A. Iger Monica C. Lozano George J. Mitchell Thomas S. Murphy Leo J. O’Donovan, S.J. Sidney Poitier Robert A.M. Stern Andrea L. Van de Kamp Raymond L. Watson Gary L. Wilson 20210F01_P01.09_v2 12/18/01 5:19 PM Page 1 The Walt Disney Company and Subsidiaries CONTENT LISTING Financial Highlights 1 Management’s Discussion and Analysis 49 Letter to Shareholders 2 Consolidated Statements of Income 60 Financial Review 10 Consolidated Balance Sheets 61 DisneyHand 14 Consolidated Statements of Cash Flows 62 Parks and Resorts 18 Consolidated Statements of Stockholders’ Equity 63 Walt Disney Imagineering 26 Notes to Consolidated Financial Statements 64 Studio Entertainment 28 Quarterly Financial Summary 77 Media Networks 36 Selected Financial Data 78 Broadcast Networks 37 Management’s Responsibility of Financial Statements 79 Cable Networks 38 Report of Independent Accountants 79 Consumer Products 44 Board of Directors and Corporate Executive Officers 80 Walt Disney International 48 FINANCIAL HIGHLIGHTS (In millions, except per share data) 2001 2000 Revenues(1) $25,256 $25,356 Segment operating income(1) 4,038 4,124 Diluted earnings per share before the cumulative effect of accounting changes, excluding restructuring and impairment charges and gain on the sale of businesses(1) 0.72 0.72 Cash flow from operations 3,048 3,755 Borrowings 9,769 9,461 Stockholders’ equity 22,672 24,100 (1) Pro forma revenues, segment operating income and earnings per share reflect the sale of Fairchild Publications, the acquisition of Infoseek, the conversion of Internet Group common stock into Disney common stock and the closure of the GO.com portal business as if these events and the adoption of SOP 00-2 had occurred at the beginning of fiscal 2000, eliminating the one-time impact of those events. -

Xavier Newswire

Xavier University Exhibit All Xavier Student Newspapers Xavier Student Newspapers 2008-02-20 Xavier University Newswire Xavier University (Cincinnati, Ohio) Follow this and additional works at: https://www.exhibit.xavier.edu/student_newspaper Recommended Citation Xavier University (Cincinnati, Ohio), "Xavier University Newswire" (2008). All Xavier Student Newspapers. 529. https://www.exhibit.xavier.edu/student_newspaper/529 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Xavier Student Newspapers at Exhibit. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Xavier Student Newspapers by an authorized administrator of Exhibit. For more information, please contact [email protected]. What’s up with Justin Dolleman? Spice up your life Check out the latest installment of Where are they The Spice Girls hit Chicago last week, and long-time fan now?, and find out where he is playing Katie Rosenbaum was there to recount the concert Sports, pg. 8 Arts & Entertainment, pg. 10 week of XAVIER NEWSWIRE Februrary 20, 2008 Volume XCIII, Issue 19 Published since 1915 by the students of Xavier University www.xavier.edu/newswire Controversy taints SGA election Xavier to Scanlon wins 51.3 to 48.7 percent Election problems include improper increase despite sanction; Gamboa appeal denied votes, early poll closing, student apathy tuition PATRICK STEVENSON New costs will not Editor-in-Chief affect upperclasses The new triumvirate of the Xavier Student Government As- KELLY SHAW sociation will enter office amid a Senior News Writer maelstrom of controversy, voting Tuition rates were increased irregularities, campaign violations last December, making a year at and disappointing voter turnout. Xavier $26,250. -

A La Carte Television: a Solution to Online Piracy?

A LA CARTE TELEVISION: A SOLUTION TO ONLINE PIRACY? Carson S. Walker I. INTRODUCTION Television piracy is nothing new. From the first successful television transmission in 1927,' to the invention of cable in the 1940s,2 digital video recorders ("DVR") in the late 1990s,3 and products that allow users to watch television shows remotely, such as Slingbox,4 television is a constantly evolving product.' Alongside this remarkable evolution an underground market for television piracy has emerged.' Despite decades of growing concern from cable and satellite providers, networks, and content owners, little progress has been made in curbing piracy.' Consequently, it is no coincidence that the rise in piracy has paralleled increasing subscription fees.' The history of television, whether broadcast, J.D., May 2012, The Catholic University of America, Columbus School of Law. Carson would like to thank his friends and family, especially his fianc6e, for their patience, love, and support during the writing of this article, as well as Preston Thomas for his expert advice, and the CommLaw Conspectus staff for their guidance throughout the process. I History of Communications - Historical Periods in Television Technology: 1880-1929, FCC, http://commcns.org/L6uNAm (last visited Apr. 15, 2012). 2 id John Markoff, Netscape Pioneer to Invest in Smart VCR, N.Y. TIMES, Nov. 9, 1998, htt://commcns.org/LbhJQr. About Sling Media, SLINGBOx, http://commcns.org/JjwR7x (last visited Apr. 15, 2012). See HistoricalPeriods in Television Technology, FCC, http://commcns.org/JTbNc8 (last visited Apr. 15, 2012) (discussing the technology and evolution of television). 6 Cont'1 Cablevision, Inc. v. -

What Happened to Goldman Sachs: an Insider’S Story of Organizational Drift and Its

What Happened to Goldman Sachs: An Insider’s Story of Organizational Drift and its Unintended Consequences Steven G. Mandis Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Science COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2014 ©2013 Steven G. Mandis All Rights Reserved Abstract What Happened to Goldman Sachs: An Insider’s Story of Organizational Drift and its Unintended Consequences Steven G. Mandis This is the story of the slow evolution of Goldman Sachs – addressing why and how the firm changed from an ethical standard to a legal one as it grew to be a leading global corporation. In What Happened to Goldman Sachs, Steven G. Mandis uncovers the forces behind what he calls Goldman’s “organizational drift.” Drawing from his firsthand experience; sociological research; analysis of SEC, congressional, and other filings; and a wide array of interviews with former clients, detractors, and current and former partners, Mandis uncovers the pressures that forced Goldman to slowly drift away form the very principles on which its reputation was built. Mandis evaluates what made Goldman Sachs so successful in the first place, how it responded to pressures to grow, why it moved away from the values and partnership culture that sustained it for so many years, what forces accelerated this drift, and why insiders can’t – or won’t – recognize this crucial change. Combining insightful analysis with engaging storytelling, Mandis has written an insider’s history that offers invaluable perspectives to business leaders interested in understanding and managing organizational drift in their own firms. -

Cycling As a Political Act: the Framing and Culture That Create a New Social Movement

University of Kentucky UKnowledge University of Kentucky Master's Theses Graduate School 2010 CYCLING AS A POLITICAL ACT: THE FRAMING AND CULTURE THAT CREATE A NEW SOCIAL MOVEMENT Mitchael Lee Schwartz University of Kentucky, [email protected] Right click to open a feedback form in a new tab to let us know how this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Schwartz, Mitchael Lee, "CYCLING AS A POLITICAL ACT: THE FRAMING AND CULTURE THAT CREATE A NEW SOCIAL MOVEMENT" (2010). University of Kentucky Master's Theses. 6. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/gradschool_theses/6 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at UKnowledge. It has been accepted for inclusion in University of Kentucky Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of UKnowledge. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ABSTRACT OF THESIS CYCLING AS A POLITICAL ACT: THE FRAMING AND CULTURE THAT CREATE A NEW SOCIAL MOVEMENT This study analyzes the bicycling community of Lexington, Kentucky. Interviews and participant observation were conducted in order to better understand the structure of Lexington’s cycling community, revealing three prominent groups/types of cyclists: (1) road cyclists, (2) underground/urban cyclists, and (3) commuters. The characteristics of each group are discussed, with particular attention devoted to the underground/urban cyclists, due to their politically-minded culture. Building from prior social movement literature, the unique framing processes of the underground/urban cycling group are analyzed in order to explore the group as a new social movement. Finally, the potential for a broader cycling movement based upon interests common to all cyclists is discussed. -

![Towards Understanding the Information Ecosystem Through the Lens of Multiple Web Communities Arxiv:1911.10517V1 [Cs.SI] 24](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/0426/towards-understanding-the-information-ecosystem-through-the-lens-of-multiple-web-communities-arxiv-1911-10517v1-cs-si-24-5150426.webp)

Towards Understanding the Information Ecosystem Through the Lens of Multiple Web Communities Arxiv:1911.10517V1 [Cs.SI] 24

Towards Understanding the Information Ecosystem Through the Lens of Multiple Web Communities Savvas Zannettou A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of Cyprus University of Technology. arXiv:1911.10517v1 [cs.SI] 24 Nov 2019 Department of Electrical Engineering, Computer Engineering and Informatics Cyprus University of Technology November 26, 2019 Abstract The Web consists of numerous Web communities, news sources, and services, which are often ex- ploited by various entities for the dissemination of false or otherwise malevolent information. Yet, we lack tools and techniques to effectively track the propagation of information across the multiple diverse communities, and to capture and model the interplay and influence between them. Further- more, we lack a basic understanding of what the role and impact of some emerging communities and services on the Web information ecosystem are, and how such communities are exploited by bad actors (e.g., state-sponsored trolls) that spread false and weaponized information. In this thesis, we shed some light on the complexity and diversity of the information ecosystem on the Web by presenting a typology that includes the various types of false information, the involved actors as well as their possible motives. Then, we follow a data-driven cross-platform quantitative approach to analyze billions of posts from Twitter, Reddit, 4chan’s Politically Incorrect board (/pol/), and Gab, to shed light on: 1) how news and image-based memes travel from one Web community to another and how we can model and quantify the influence between the various Web communities; 2) characterizing the role of emerging Web communities and services on the information ecosystem, by studying Gab and two popular Web archiving services, namely the Wayback Machine and archive.is; and 3) how popular Web communities are exploited by state-sponsored actors for the purpose of spreading disinformation and sowing public discord. -

![Hosbrutality Podcast Interviews Dave Specter of Bells up Winery [TRANSCRIPT] Broadcast September 8, 2020](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/7370/hosbrutality-podcast-interviews-dave-specter-of-bells-up-winery-transcript-broadcast-september-8-2020-5397370.webp)

Hosbrutality Podcast Interviews Dave Specter of Bells up Winery [TRANSCRIPT] Broadcast September 8, 2020

AUDIO: HosBrutality Podcast Interviews Dave Specter of Bells Up Winery [TRANSCRIPT] Broadcast September 8, 2020 Stefan Czarnecki (00:01): Hello, this is Stefan from HosBrutality. And I wanted to take a minute just to tell you a little bit about Anchor. Anchor is a podcasting platform and website, and it's really helped us get our start with HosBrutality. It's easy to upload your audio or record right through the website. You can also set up other podcasting platforms, right through Anchor. They'll even connect you with businesses for monetization. So if you have something to say, consider starting your own podcast with Anchor. Stefan Czarnecki (00:41): Welcome to hospitality. I'm Stefan Czarnecki of Black Tie Tours. With me as always Wesley Jones of Tour Cascadia and local artist Cole Rogers. Cole Rogers (00:50): That's what they call me. Stefan Czarnecki (00:51): Yeah, it is. And we are joined today by a special guest. We are at Bells Up Winery here in the the Chehalem AVA. And,uthis person is a musician, Dave Specter (01:05): A former musician. Stefan Czarnecki (01:05): A winemaker, Dave Specter (01:05): That's correct. Stefan Czarnecki (01:08): And most importantly an Orlando magic fan? Dave Specter (01:12): Oh, it happens to the best of us. Sometimes. Stefan Czarnecki (01:13): David Specter. Well, the worst of us. David Specter's here. Dave Specter (01:16): Thank you Stefan. Stefan Czarnecki (01:18): Why the Magic? Why? AUDIO: HosBrutality Podcast Interviews Dave Specter of Bells Up Winery [TRANSCRIPT] Broadcast September 8, 2020 Dave Specter (01:19): See, I have a tortured, tortured soul.