The North York Moors Re-Visited

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

LCA Introduction

The Hambleton and Howardian Hills CAN DO (Cultural and Natural Development Opportunity) Partnership The CAN DO Partnership is based around a common vision and shared aims to develop: An area of landscape, cultural heritage and biodiversity excellence benefiting the economic and social well-being of the communities who live within it. The organisations and agencies which make up the partnership have defined a geographical area which covers the south-west corner of the North York Moors National Park and the northern part of the Howardian Hills Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty. The individual organisations recognise that by working together resources can be used more effectively, achieving greater value overall. The agencies involved in the CAN DO Partnership are – the North York Moors National Park Authority, the Howardian Hills Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty, English Heritage, Natural England, Forestry Commission, Environment Agency, Framework for Change, Government Office for Yorkshire and the Humber, Ryedale District Council and Hambleton District Council. The area was selected because of its natural and cultural heritage diversity which includes the highest concentration of ancient woodland in the region, a nationally important concentration of veteran trees, a range of other semi-natural habitats including some of the most biologically rich sites on Jurassic Limestone in the county, designed landscapes, nationally important ecclesiastical sites and a significant concentration of archaeological remains from the Neolithic to modern times. However, the area has experienced the loss of many landscape character features over the last fifty years including the conversion of land from moorland to arable and the extensive planting of conifers on ancient woodland sites. -

North York Moors and Cleveland Hills Area Profile: Supporting Documents

National Character 25. North York Moors and Cleveland Hills Area profile: Supporting documents www.gov.uk/natural-england 1 National Character 25. North York Moors and Cleveland Hills Area profile: Supporting documents Introduction National Character Areas map As part of Natural England’s responsibilities as set out in the Natural Environment 1 2 3 White Paper , Biodiversity 2020 and the European Landscape Convention , we are North revising profiles for England’s 159 National Character Areas (NCAs). These are areas East that share similar landscape characteristics, and which follow natural lines in the landscape rather than administrative boundaries, making them a good decision- Yorkshire making framework for the natural environment. & The North Humber NCA profiles are guidance documents which can help communities to inform their West decision-making about the places that they live in and care for. The information they contain will support the planning of conservation initiatives at a landscape East scale, inform the delivery of Nature Improvement Areas and encourage broader Midlands partnership working through Local Nature Partnerships. The profiles will also help West Midlands to inform choices about how land is managed and can change. East of England Each profile includes a description of the natural and cultural features that shape our landscapes, how the landscape has changed over time, the current key London drivers for ongoing change, and a broad analysis of each area’s characteristics and ecosystem services. Statements of Environmental Opportunity (SEOs) are South East suggested, which draw on this integrated information. The SEOs offer guidance South West on the critical issues, which could help to achieve sustainable growth and a more secure environmental future. -

10 Decemberr Spire 2016

The Magazine of the Church of England in Great Ayton with Easby & Newton under Roseberry Parishes DECEMBER 2016 & JANUARY 2017 Contents Page 2 December & January Diary Page 3 Christmas Services Page 4 Vicar’s Letter Page 6 Wydale 2017 & Blowers Page 7 Love in a Box Page 8 Christmas Notices Bradley School of Dance & Guests Page 9 Chloe’s Chinese Tale Present Page 10 Charitable Giving 2016 Page 12 OLIVER A Retreat to Remember Page 13 In Christ Church Hall A Family Tradition Page 14 Tuesday 6th, Wednesday 7th, Friday 9th December Yorkshire Cancer News th at 7pm. Saturday 10th, Sunday 11 at 1.30pm Page 15 Children’s Society News Tickets £7.00 adults and £4.50 children. Special Page 16 OAP tickets available for performance on Tuesday Great Ayton First Responders evening. Page 18 From the Registers Tickets will be on sale at Great Ayton Discovery Page 19 Centre or by calling the box office on Malcolm’s Bits & Bobs 01642 723250. 60p www.christchurchgreatayton.org.uk 1 DECEMBER & JANUARY 2 Fri 9.30am Holy Communion & Stokesley Deanery Chapter Meeting 4 Sun ADVENT 2 8am Holy Communion; 9.15am Parish Communion; 11am Holy Communion at Saint Oswald’s; 12.15pm Holy Baptism at St Oswald’s; 4pm Masons Carol Service. 5 Mon 2pm Coffee Lounge Christmas Carols and Cuppa. 6 Tues 1.30pm Marwood School Christmas Production in Church Hall 7pm Opening Night of Oliver. FOR CHRISTMAS SERVICES SEE PANEL OPPOSITE 8 Thurs 6pm Marwood School Christmas Production in Church Hall. 11 Sun ADVENT 3 8am Holy Communion; 9.15am Parish Communion 11am Christmas Come & Praise. -

Moors Web Link Terms & Conditions

Information for Moorsweb Internet Subscribers and summarised Terms & Conditions This document provides a plain English summary of: • The Internet service • The summarised terms and conditions for the supply of Moorsweb internet services • Your use of these services and acceptable use. This document and the documents containing the full details of the terms and conditions, the acceptable use policy, the pricing policy and the definitions, forms the contract between Moorsweb and yourself for the supply and purchase of the internet service. Moorsweb reserves the right to provide updated versions of these documents as required. Background to the service Moors Web Link is a broadband internet Community Area Network (CAN) project. It is organised by a committee who are elected by an annual public meeting (AGM), and governed by a formal constitution. Moors Web Link’s objective is to provide a broadband internet service to subscribers in Bransdale, Rosedale, Farndale, Rudland, Harland, Gillamoor and Fadmoor and surrounding areas. Yorkshire Forward (YF) and North Yorkshire County Council (NYCC) via NYnet have funded set-up of the CAN in years gone by for which we are extremely grateful, but it is now a self-funding community network. You may contact any of the committee as your local representatives, but most routine communications should be sent to Signa Technologies, email [email protected] and tel 01423 900433. In 2009 the CAN was extended to Beadlam Rigg, again kindly funded by a grant from Yorkshire Forward. Further extensions have been achieved since then. Consideration will be given to extending it further should requests be received, and an extension to Hutton-le-hole is underway in 2016. -

MOORSBUS and the NATIONAL PARK AUTHORITY V3

MOORSBUS and THE NATIONAL PARK AUTHORITY v3 For over 40 years Moorsbus has played a Moorsbus offers a cost-effective way of delivering key role in enabling access to the North National Park purposes, including key elements of the Authority’s Sustainability Objectives and DEFRA’s ‘8 York Moors: ‘for all, regardless of wealth or point plan for England’s National Parks’. social class’ in the words of the original National Parks’ legislation. Rural transport: As bus services have diminished over the years, public expensive to provide, expensive to use transport access to the North York Moors is now at its lowest since the Park was designated over 60 years A sparse rural population can never provide enough ago. passengers to generate a reasonable return without continued investment. This is made worse by the fact Moorsbus has increasingly shouldered sole that many - but certainly not all - rural dwellers have responsibility for providing accessibility to a large area access to a car, making the cost of providing services of the National Park – including its two national park for a small population even more expensive. centres. It is responding to climate change, reducing The elderly or disabled can use a national bus pass but CO2 emissions, improving road safety, as well as contributing positively to health, well-being, social this sees only a marginal return for Moorsbus (e.g. cohesion and supporting the local economy. about £1 for the full journey from York to Danby). Most rural bus journeys are longer than urban ones, Moorsbus was funded for many years by the National this giving a very poor return per pass-user. -

Residential Development Opportunity Main Street, Fadmoor, North York Moors National Park

CHARTERED SURVEYORS • AUCTIONEERS • VALUERS • LAND & ESTATE AGENTS • FINE ART & FURNITURE ESTABLISHED 1860 RESIDENTIAL DEVELOPMENT OPPORTUNITY MAIN STREET, FADMOOR, NORTH YORK MOORS NATIONAL PARK A RARE DEVELOPMENT OPPORTUNITY WITHIN THIS ATTRACTIVE NATIONAL PARK VILLAGE BUILDING PLOT WITH FULL PLANNING CONSENT TO CONSTRUCT A 3 BEDROOM HOUSE STONE BARN WITH FULL PLANNING CONSENT FOR CONVERSION TO A 3 BEDROOM DWELLING LAND EXTENDING TO APPROXIMATELY 13.8 ACRES FOR SALE BY PRIVATE TREATY AS A WHOLE OR IN 4 LOTS 15 Market Place, Malton, North Yorkshire, YO17 7LP Tel: 01 653 697820 Fax: 01653 698305 Email : [email protected] Website : www.cundalls.co.uk SITUATION internal floor area of around 118m 2. The plans provide for the following accommodation: Fadmoor is a pretty moorland village, with a broad village green edged with stone cottages and farmhouses. The Hall 3.5m x 1.7m village is set approximately 0.5 miles to the west of Sitting Room 6.4m x 3.3m Gillamoor and two miles north of Kirkbymoorside. Dining Kitchen 6.4m x 3.2m, plus 2.9m x 1.5m Kirkbymoorside is an attractive market t own which is often Utility Room 2.9m x 1.8m referred to as the gateway to the North York Moors Lobby 1.7m x 1.5m National Park. The town is well equipped with a wide range Cloakroom 1.7m x 1.1m of amenities enjoys a traditional weekly market and a golf First Floor course. Landing Bedroom One 4.0m x 3.3m The subject propery currently forms part of Waingate Farm, EnSuite Shower Room 2.1m x 1.8m (max) towards the northern periphery of the village and can be Bedroom Two 3.2m x 3.1m identified by our ‘For Sale’ board. -

The Ecology of the in the North York Moors National Park

The ecology of the invasive moss Campylopus introflexus in the North York Moors National Park by Miguel Eduardo Equihua Zamora A thesis presented for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Biology at the University of York November 1991 I hereby declare that the work presented in this thesis is the result of my own investigation and has not been accepted in previous applications for the award of a degree. Exceptions to this declaration are part of the field data used in chapter 4, which was collected and made available to me by Dr. M.B. Usher. The distribution map on Campylopus introflexus was provided by P.T. Harding (Biological Records Centre, ITE, Monks Wood). R.C. Palmer (Soil Survey and Land Research Centre, University of York) made available to me the soil and climatological data of the area, and helped me to obtain the corresponding interpolation values for the sampled sites. Miguel Eduardo Equihua Zamora 1 CONTENTS page Acknowledgements . 4 Abstract................................................. 5 1. Introduction 1.1 The invader: Campylopus introflexus ..................... 7 The invasion of the Northern Hemisphere ............... 7 Taxonomyand identity ............................ 13 Ecology....................................... 16 1.2 The problem ...................................... 19 1.3 Hypothetical mechanisms of interaction ................... 22 2. Aims of the research ......................................28 3. Description of the study area .................................29 4.Ecological preferences of Campylopus introflexus in the North York Moors National Park 4.1 Introduction ....................................... 35 4.2 Methods ......................................... 36 Thefuzzy c-means algorithm ........................ 39 Evaluation of the associations ........................ 43 Desiccation survival of the moss carpets ................ 44 4.3 Results .......................................... 45 Vegetationanalysis ............................... 45 Assessment of moss associations ..................... -

Der Europäischen Gemeinschaften Nr

26 . 3 . 84 Amtsblatt der Europäischen Gemeinschaften Nr . L 82 / 67 RICHTLINIE DES RATES vom 28 . Februar 1984 betreffend das Gemeinschaftsverzeichnis der benachteiligten landwirtschaftlichen Gebiete im Sinne der Richtlinie 75 /268 / EWG ( Vereinigtes Königreich ) ( 84 / 169 / EWG ) DER RAT DER EUROPAISCHEN GEMEINSCHAFTEN — Folgende Indexzahlen über schwach ertragsfähige Böden gemäß Artikel 3 Absatz 4 Buchstabe a ) der Richtlinie 75 / 268 / EWG wurden bei der Bestimmung gestützt auf den Vertrag zur Gründung der Euro jeder der betreffenden Zonen zugrunde gelegt : über päischen Wirtschaftsgemeinschaft , 70 % liegender Anteil des Grünlandes an der landwirt schaftlichen Nutzfläche , Besatzdichte unter 1 Groß vieheinheit ( GVE ) je Hektar Futterfläche und nicht über gestützt auf die Richtlinie 75 / 268 / EWG des Rates vom 65 % des nationalen Durchschnitts liegende Pachten . 28 . April 1975 über die Landwirtschaft in Berggebieten und in bestimmten benachteiligten Gebieten ( J ), zuletzt geändert durch die Richtlinie 82 / 786 / EWG ( 2 ), insbe Die deutlich hinter dem Durchschnitt zurückbleibenden sondere auf Artikel 2 Absatz 2 , Wirtschaftsergebnisse der Betriebe im Sinne von Arti kel 3 Absatz 4 Buchstabe b ) der Richtlinie 75 / 268 / EWG wurden durch die Tatsache belegt , daß das auf Vorschlag der Kommission , Arbeitseinkommen 80 % des nationalen Durchschnitts nicht übersteigt . nach Stellungnahme des Europäischen Parlaments ( 3 ), Zur Feststellung der in Artikel 3 Absatz 4 Buchstabe c ) der Richtlinie 75 / 268 / EWG genannten geringen Bevöl in Erwägung nachstehender Gründe : kerungsdichte wurde die Tatsache zugrunde gelegt, daß die Bevölkerungsdichte unter Ausschluß der Bevölke In der Richtlinie 75 / 276 / EWG ( 4 ) werden die Gebiete rung von Städten und Industriegebieten nicht über 55 Einwohner je qkm liegt ; die entsprechenden Durch des Vereinigten Königreichs bezeichnet , die in dem schnittszahlen für das Vereinigte Königreich und die Gemeinschaftsverzeichnis der benachteiligten Gebiete Gemeinschaft liegen bei 229 beziehungsweise 163 . -

Design Guide 1 Cover

PARTONE North York Moors National Park Authority Local Development Framework Design Guide Part 1: General Principles Supplementary Planning Document North York Moors National Park Authority Design Guide Part 1: General Principles Supplementary Planning Document Adopted June 2008 CONTENTS Contents Page Foreword 3 Section 1: Introducing Design 1.1 Background 4 1.2 Policy Context 4 1.3 Design Guide Supplementary Planning Documents 7 1.4 Aims and Objectives 8 1.5 Why do we need a Design Guide? 9 Section 2: Design in Context 2.1 Background 10 2.2 Landscape Character 11 2.3 Settlement Pattern 19 2.4 Building Characteristics 22 Section 3: General Design Principles 3.1 Approaching Design 25 3.2 Landscape Setting 26 3.3 Settlement Form 27 3.4 Built Form 28 3.5 Sustainable Design 33 Section 4: Other Statutory Considerations 4.1 Conservation Areas 37 4.2 Listed Buildings 37 4.3 Public Rights of Way 38 4.4 Trees and Landscape 38 4.5 Wildlife Conservation 39 4.6 Archaeology 39 4.7 Building Regulations 40 Section 5: Application Submission Requirements 5.1 Design and Access Statements 42 5.2 Design Negotiations 45 5.3 Submission Documents 45 Appendix A: Key Core Strategy and Development Policies 47 Appendix B: Further Advice and Information 49 Appendix C: Glossary 55 Map 1: Landscape Character Types and Areas 13 Table 1: Landscape Character Type Descriptors 14 • This document can be made available in Braille, large print, audio and can be translated. Please contact the Planning Policy team on 01439 770657, email [email protected] or call in at The Old Vicarage, Bondgate, Helmsley YO62 5BP if you require copies in another format. -

North Yorkshire Police Property Listing May 2019

Location Address Postcode Function Tenure Acomb, York Acomb Police Station, Acomb Road, Acomb, York YO24 4HA Local Police Office FREEHOLD Alverton Court HQ Alverton Court Crosby Road Northallerton DL6 1BF Headquarters FREEHOLD Alverton House 16 Crocby Road, Northallerton DL6 1AA Administration FREEHOLD Athena House, York Athena House Kettlestring Lane Clifton Moor York Eddisons (Michael Alton) 07825 343949 YO30 4XF Administration FREEHOLD Barton Motorway Post Barton Motorway Post, Barton, North Yorkshire DL10 5NH Specialist Function FREEHOLD Bedale Bedale LAP office, Wycar, Bedale, North Yorkshire DL8 1EP Local Police Office LEASEHOLD Belvedere, Pickering Belvedere Police House, Malton Road, Pickering, North Yorkshire YO18 7JJ Specialist Function FREEHOLD Boroughbridge former Police Station, 30 New Row, Borougbridge YO51 9AX Vacant FREEHOLD Catterick Garrison Catterick Garrison Police Station, Richmond Road, Catterick Garrison, North Yorkshire. DL9 3JF Local Police Office LEASEHOLD Clifton Moor Clifton Moor Police Station,Sterling Road, Clifton Moor, York YO30 4WZ Local Police Office LEASEHOLD Crosshills Glusburn Police Station, Colne Road, Crosshills, Keighley, West Yorkshire BD20 8PL Local Police Office FREEHOLD Easingwold Easingwold Police Station, Church Hill, Easingwold YO61 3JX Local Police Office FREEHOLD Eastfield, Scarborough Eastfield LAP Office,Eastfield, Scarborough YO11 3DF Local Police Office FREEHOLD Eggborough Eggborough Local Police Station, 120 Weeland Road, Eggbrough, Goole DN14 0RX Local Police Office FREEHOLD Filey -

CONTENTS 3 Please Ask for Them and Tell Others Who May Need Them

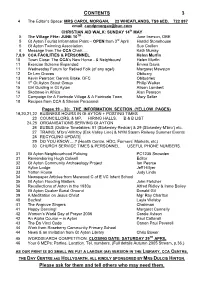

CONTENTS 3 4 The Editor’s Space: MRS CAROL MORGAN, 22 WHEATLANDS, TS9 6ED. 722 897 email: [email protected] CHRISTIAN AID WALK: SUNDAY 14th MAY 5 The Village Fête: JUNE 10TH June Imeson, OBE 5 Gt Ayton Tourist Information Point – OPEN from 3rd April Harold Stonehouse 5 Gt Ayton Twinning Association Sue Crellen 6 Message from The CCA Chair….. Kath Murray 7,8,9 CCA FACILITIES & PERSONNEL Helen Murfin 10 Town Close: The CCA’s New Home - & Neighbours! Helen Murfin 11 Exercise Scheme Expanded Emma Davis 11 Wednesday Forum for Retired Folk (of any age!) Margaret Mawston 12 Dr Len Groves Obituary 13 Kevin Pearson; Dennis Blake, DFC Obituaries 14 1st Gt Ayton Scout Group Philip Walker 15 Girl Guiding in Gt Ayton Alison Lambert 16 Skottowe in Africa Alan Pearson 17 Campaign for A Fairtrade Village & A Fairtrade Town Mary Seller 18 Recipes from CCA & Stream Personnel Pages 19 – 30: THE INFORMATION SECTION (YELLOW PAGES) 19,20,21,22 BUSINESS HOURS IN Gt AYTON + POSTING TIMES 23 COUNCILLORS, & MP. HIRING HALLS. B & B LIST 24,25 ORGANISATIONS SERVING Gt AYTON 26 BUSES (Outline Timetables: 81 (Stokesley-Redcar) & 29 (Stokesley-M’bro’) etc. 27 TRAINS: M’bro’-Whitby (Esk Valley Line) & NYM Steam Railway Summer Events 28 RECYCLING UPDATE 29 DO YOU KNOW….? (Health Centre, HDC, Farmers’ Markets, etc) 30 CHURCH SERVICE TIMES & PERSONNEL. USEFUL PHONE NUMBERS. 31 Gt Ayton Neighbourhood Policing PC1235 Snowden 31 Remembering Hugh Colwell Editor 32 Gt Ayton Community Archaeology Project Ian Pearce 33 Ayton Lodge Jeff Hillyer 33 Yatton House Judy Lindo 34 -

Highfield, Highfield Lane, Gillamoor North Yorkshire, YO62

Highfield, Highfield Lane, Gillamoor www.peterillingworth.co.uk North Yorkshire, YO62 7HX PRICE ON APPLICATION Neatly nestling within the attractive North York Moors National Park village of Gillamoor can be found this attractive period stone country house standing within a total of approximately 4.19 acres, including three fenced paddocks, approx 1.17, 1.04 and 0.5 acres. This residence has been sympathetically improved by the current owners and comprises on the ground floor: open entrance porch, entrance hall, four reception rooms, fitted kitchen with granite work surfaces and Aga, utility room, ground floor bedroom, cloakroom and boot room. The first floor can be reached by either of the two staircases, giving flexibility to provide separate accommodation for guests. Four double bedrooms all with access to their own bathroom/shower rooms. Highfield is enhanced by beamed ceilings, timber and stone flagged flooring and sealed unit double glazing. Externally a substantial games room/gym/office with kitchen area and cloakroom, three bay carport attached to the house with garage. Stone outbuildings include a workshop and stable with granary over. Set within a small separate yard can be found two stables, open store and tack room. Large lawned well stocked gardens with separate seating areas and patios, large ornamental pond with bridge and covered decked sitting out area. Tenure: We understand the property to be freehold and vacant possession will be given on completion. Services: Mains drainage, water and electricity are laid on. Oil fired central heating. Broadband to the house and office/games room. Property Tax: Band F Energy Performance Rating: Band E Easements, Rights of Way and Wayleaves: The property is sold with the benefits of all existing rights of way, water, light, drainage and other easements attaching to the property whether mentioned in these particulars or not.