Dreaming the Salinas

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Field Guide to Neotectonics of the San Andreas Fault System, Santa Cruz Mountains, in Light of the 1989 Loma Prieta Earthquake

Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey Field Guide to Neotectonics of the San Andreas Fault System, Santa Cruz Mountains, in Light of the 1989 Loma Prieta Earthquake | Q|s | Landslides (Quaternary) I yv I Vaqueros Sandstone (Oligocene) r-= I San Lorenzo Fm., Rices Mudstone I TSr I member (Eocene-Oligocene) IT- I Butano Sandstone, ' Pnil mudstone member (Eocene) Coseismic surface fractures, ..... dashed where discontinuous, dotted where projected or obscured ___ _ _ Contact, dashed where approximately located >"«»"'"" « « Fault, dotted where concealed V. 43? Strike and dip Strike and dip of of bedding overturned bedding i Vector Scale / (Horizontal Component of Displacement) OPEN-FILE REPORT 90-274 This report is preliminary and has not been reviewed for conformity with U. S. Geological Survey editorial standards (or with the North American Stratigraphic Code). Any use of trade, product, or firm names is for descriptive purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the U. S. Government. Men to Park, California April 27, 1990 Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey Field Guide to Neotectonics of the San Andreas Fault System, Santa Cruz Mountains, in Light of the 1989 Loma Prieta Earthquake David P. Schwartz and Daniel J. Ponti, editors U. S. Geological Survey Menlo Park, CA 94025 with contributions by: Robert S. Anderson U.C. Santa Cruz, Santa Cruz, CA William R. Cotton William Cotton and Associates, Los Gatos, CA Kevin J. Coppersmith Geomatrix Consultants, San Francisco, CA Steven D. Ellen U. S. Geological Survey, Menlo Park, CA Edwin L. Harp U. S. Geological Survey, Menlo Park, CA Ralph A. -

Late Cenozoic Tectonics of the Central and Southern Coast Ranges of California

OVERVIEW Late Cenozoic tectonics of the central and southern Coast Ranges of California Benjamin M. Page* Department of Geological and Environmental Sciences, Stanford University, Stanford, California 94305-2115 George A. Thompson† Department of Geophysics, Stanford University, Stanford, California 94305-2215 Robert G. Coleman Department of Geological and Environmental Sciences, Stanford University, Stanford, California 94305-2115 ABSTRACT within the Coast Ranges is ascribed in large Taliaferro (e.g., 1943). A prodigious amount of part to the well-established change in plate mo- geologic mapping by T. W. Dibblee, Jr., pre- The central and southern Coast Ranges tions at about 3.5 Ma. sented the areal geology in a form that made gen- of California coincide with the broad Pa- eral interpretations possible. E. H. Bailey, W. P. cific–North American plate boundary. The INTRODUCTION Irwin, D. L. Jones, M. C. Blake, and R. J. ranges formed during the transform regime, McLaughlin of the U.S. Geological Survey and but show little direct mechanical relation to The California Coast Ranges province encom- W. R. Dickinson are among many who have con- strike-slip faulting. After late Miocene defor- passes a system of elongate mountains and inter- tributed enormously to the present understanding mation, two recent generations of range build- vening valleys collectively extending southeast- of the Coast Ranges. Representative references ing occurred: (1) folding and thrusting, begin- ward from the latitude of Cape Mendocino (or by these and many other individuals were cited in ning ca. 3.5 Ma and increasing at 0.4 Ma, and beyond) to the Transverse Ranges. This paper Page (1981). -

Possible Correlations of Basement Rocks Across the San Andreas, San Gregorio- Hosgri, and Rinconada- Reliz-King City Faults

Possible Correlations of Basement Rocks Across the San Andreas, San Gregorio- Hosgri, and Rinconada- Reliz-King City Faults, U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY PROFESSIONAL PAPER 1317 Possible Correlations of Basement Rocks Across the San Andreas, San Gregorio- Hosgri, and Rinconada- Reliz-King City Faults, California By DONALD C. ROSS U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY PROFESSIONAL PAPER 1317 A summary of basement-rock relations and problems that relate to possible reconstruction of the Salinian block before movement on the San Andreas fault UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE, WASHINGTON: 1984 DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR WILLIAM P. CLARK, Secretary U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Dallas L. Peck, Director Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Boss, Donald Clarence, 1924- Possible correlations of basement rocks across the San Andreas, San Gregrio-Hosgri, and Rinconada-Reliz-King City faults, California (U.S. Geological Survey Bulletin 1317) Bibliography: p. 25-27 Supt. of Docs, no.: 119.16:1317 1. Geology, structural. 2. Geology California. 3. Faults (geology) California. I. Title. II. Series: United States. Geological Survey. Professional Paper 1317. QE601.R681984 551.8'09794 84-600063 For sale by the Distribution Branch, Text Products Section, U.S. Geological Survey, 604 South Pickett St., Alexandria, VA 22304 CONTENTS Page Abstract _____________________________________________________________ 1 Introduction __________________________________________________________ 1 San Gregorio-Hosgri fault zone ___________________________________________ 3 San Andreas -

Salinas Valley Groundwater Basin, Forebay Aquifer Subbasin • Groundwater Basin Number: 3-4.04 • County: Monterey • Surface Area: 94,000 Acres (147 Square Miles)

Central Coast Hydrologic Region California’s Groundwater Salinas Valley Groundwater Basin Bulletin 118 Salinas Valley Groundwater Basin, Forebay Aquifer Subbasin • Groundwater Basin Number: 3-4.04 • County: Monterey • Surface Area: 94,000 acres (147 square miles) Basin Boundaries and Hydrology The Salinas Valley Groundwater Basin – Forebay Aquifer Subbasin occupies the central portion of the Salinas Valley and extends from the town of Gonzales in the north to approximately three miles south of Greenfield. The subbasin is bounded to the west by the contact of Quaternary terrace deposits of the subbasin with Mesozoic metamorphic rocks (Sur Series) or middle Miocene marine sedimentary rocks (Monterey Shale) of the Sierra de Salinas. To the east, the boundary is the contact of Quaternary terrace deposits or alluvium with granitic rocks of the Gabilan Range. The northern subbasin boundary is shared with the Salinas Valley –180/400-Foot Aquifer and –Eastside Aquifer and represents the southern limit of confining conditions in the 180/400-Foot Aquifer Subbasin. The southern boundary is shared with the Salinas Valley – Upper Valley Aquifer Subbasin and generally represents the southern limit of confining conditions above the 400-Foot Aquifer (MW 1994). This boundary also represents a constriction of the Valley floor caused by encroachment from the west by the composite alluvial fan of Arroyo Seco and Monroe Creek. Intermittent streams such as Stonewall and Chalone Creeks drain the western slopes of the Gabilan Range and flow westward across the subbasin toward the Salinas River. The major tributary drainage to the Salinas River in the Salinas Valley is Arroyo Seco, which drains a large portion of the Sierra de Salinas west of Greenfield. -

Greater Salinas Area Plan

GREATER SALINAS AREA PLAN A PART OF THE MONTEREY COUNTY GENERAL PLAN MONTEREY COUNTY BOARD OF SUPERVISORS Sam Karas, Chairman Marc Del Piero Dusan Petrovic Barbara Shipnuck Karin Strasser Kauffman MONTEREY COUNTY PLANNING COMMISSIONERS Calvin Reaves, Chairman Thomas Mill, 1st Vice Chairman Lynn Riddle, 2nd Vice Chairwoman Peter Cailotto Louis Calcagno Tom Glau David Hendrick Manuel Jimenez Jo Stallard GREATER SALINAS AREA PLAN CITIZENS ADVISORY COMMITTEE Hans Sappok, Chairman Michael Boggiatto Ellyse Burke Donald Cranford Hardy Nielsen William Pennycook Kevin Quinn Bruno Sala The Committee dedicates this report to the memory of fellow CAC member Jack Coakley MONTEREY COUNTY PLANNING DEPARTMENT Robert Slimmon, Jr., Director of Planing Raymond W. Lamb, Assistant Director of Planning Project Staff: Frank E. Brunings, Project Planner Steve Early, Graphics Supervisor Steven Sigala, Project Graphics Carmelia Moon, Word Processing Approved by the Monterey County Planning Commission January 9, 1985. 1 UPDATE INDEX GREATER SALINAS AREA PLAN As Adopted by the Monterey County Board of Supervisors for the following dates: 1. July 14, 1987 - Adopt Boronda Neighborhood Improvement Plan and Land Use Desig- nations. 2. November 29, 1988 - MAP CHANGE - APN 177-071-16 - Change land use designation from "Farmlands" to "Commerical." 3. August 24, 1993 - MAP CHANGE - APN 153-111-3, 4, 5, 6, 7 - Change land use designation from "Farmlands, 40 Acre Minimum" to "Low Density Residential, 2.5 Acres/Unit". 4. August 24, 1993 - MAP CHANGE - APN 137-141-20 - Change land use designation from "Farmlands, 40 Acre Minimum" to "Industrial". 5. December 14, 1993 - MAP CHANGE - APNs 177-051-033-000; 177-054-004-000; 177-055-007- 000 SPRECKELS - Change land use designation from "Farmlands, 40 Acre Minimum" to "High Density Residential, 5.1 Units/Acre." 6. -

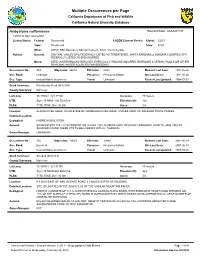

Multiple Occurrences Per Page California Department of Fish and Wildlife California Natural Diversity Database

Multiple Occurrences per Page California Department of Fish and Wildlife California Natural Diversity Database Ambystoma californiense Element Code: AAAAA01180 California tiger salamander Listing Status: Federal: Threatened CNDDB Element Ranks: Global: G2G3 State: Threatened State: S2S3 Other: CDFW_SSC-Species of Special Concern, IUCN_VU-Vulnerable Habitat: General: CENTRAL VALLEY DPS FEDERALLY LISTED AS THREATENED. SANTA BARBARA & SONOMA COUNTIES DPS FEDERALLY LISTED AS ENDANGERED. Micro: NEED UNDERGROUND REFUGES, ESPECIALLY GROUND SQUIRREL BURROWS & VERNAL POOLS OR OTHER SEASONAL WATER SOURCES FOR BREEDING Occurrence No. 249 Map Index: 26014 EO Index: 5033 Element Last Seen: 1991-05-26 Occ. Rank: Unknown Presence: Presumed Extant Site Last Seen: 1991-05-26 Occ. Type: Natural/Native occurrence Trend: Unknown Record Last Updated: 2004-07-01 Quad Summary: Palo Escrito Peak (3612144) County Summary: Monterey Lat/Long: 36.47562 / -121.47102 Accuracy: 80 meters UTM: Zone-10 N4037790 E636975 Elevation (ft): 120 PLSS: T17S, R05E, Sec. 06 (M) Acres: 0.0 Location: ALONG RIVER ROAD, 0.5 MILE SSE OF GONZALES RIVER ROAD, 5 MILES WEST OF SOLEDAD STATE PRISON. Detailed Location: Ecological: HYBRID POPULATION. General: SHAFFER SITE #242. CTS PRESENT ON 26 MAY 1991; NUMBER AND LIFESTAGE UNKNOWN. GENETIC ANALYSIS BY SHAFFER FOUND THESE CTS TO BE HYBRIDS WITH A. TIGRINUM. Owner/Manager: UNKNOWN Occurrence No. 992 Map Index: 70029 EO Index: 70882 Element Last Seen: 2007-06-14 Occ. Rank: Excellent Presence: Presumed Extant Site Last Seen: 2007-06-14 Occ. Type: Natural/Native occurrence Trend: Unknown Record Last Updated: 2007-09-26 Quad Summary: Soledad (3612143) County Summary: Monterey Lat/Long: 36.45803 / -121.31758 Accuracy: 80 meters UTM: Zone-10 N4036068 E650756 Elevation (ft): 463 PLSS: T17S, R06E, Sec. -

Groundwater Recharge on East Side Soils of the Salinas Valley Richard

Groundwater Recharge on East Side Soils of the Salinas Valley Richard Smith1, Michael Cahn1, Tamara Voss2, Toby O’Geen3, Eric Brennan4, Karen Lowell5 and Mark Bolda6 1 – UC Cooperative Extension, Monterey County; 2 – Monterey County Water Resources Agency; 3 – Dept of Land Air and Water Resources, UC Davis; 4 – USDA Agricultural Research Service; 5 –USDA Natural Resources Conservation Service; 6 – UC Cooperative Extension, Santa Cruz County. Summary: After four years of drought, groundwater levels in the Salinas Valley are at historically low levels which threaten to adversely affect farming in the Salinas Valley. Given the prospect of a strong El Niño this coming winter, it seems prudent to plan to capture as much of the rainfall as possible to maximize infiltration into the soil and recharge groundwater. The east side of the Salinas Valley is particularly hard hit because it receives a lower proportion of recharge from the Salinas River than other hydrological subunits in the Salinas Valley and its water levels have fallen to lower levels. Low residue cover crops have been shown to effectively increase rainwater infiltration on Chualar loam soils and they provide a practice that we can employ to increase groundwater recharge. Given the low water status of the aquifers and the forecast for significant rainfall, there is an opportunity to proactively implement practices that can maximize water capture this winter. In this article we discuss practices growers can employ in production fields and on farm edges to maximize rainwater infiltration and restore groundwater resources. Introduction: The four years of drought have left groundwater levels in much of the Salinas Valley are at historically low levels (Figure 1). -

San Andreas Fault System

REGIONAL TECTONICS AND STRUCTURAL EVOLUTION OF THE MONTEREY BAY REGION, CENTRAL CALIFORNIA H. Gary Greene Branch of Pacific Marine Geology U.S. Geological Survey 345 Middlefield Road, MS-999 Menlo Park, California 94025 ABSTRACT INTRODUCTION The tectonic and structural evolution of the Monterey The coastal region of central California from Mon Bay region of central California is complex and diverse. terey Bay to San Francisco, encompasses a geologically Onshore and offshore geologic investigations during the complex part of the continental margin of North America, past two decades indicate that the region has been subjected the California Coast Ranges Province (Fig. .1). Interest and to at least two different types of tectonic forces; to a pre knowledge of the geology of this region has increased sig Neogene orthogonal converging plate (subduction) and a nificantly over the past two decades due to detailed map Neogene-Quaternary obliquely converging plate (transform) ping and the recasting of the Tertiary tectonic history of the tectonic influence. Present-day structural fabric, however, area in light of plate tectonic concepts (McKenzie and appears to have formed during the transition from a sub Parker, 1967; Morgan, 1968; Atwater, 1970; Atwater and ducting regime to transform regime and since has been Molnar, 1973; McWilliams and Howell, 1982; Howell et al., modified by both strike-slip and thrust movement. 198Sa; McCulloch, 1987). The purpose of this paper is to review the structure and tectonics of the region, with empha Monterey Bay region is part of an exotic allocthonous sis on the Monterey Bay area. structural feature known as the Salinian block or Salinia tectonostratigraphic terrane. -

Characteristics ______

Q. Watershed Characteristics ________________________________________________________________ Chapter Watershed Characteristics “Any river is really the summation of the whole valley. To think of Qit as nothing but the water is to ignore the greater part.” --Hal Borland Q.1 Introduction Once a small agricultural community of 14,0001 people, Salinas today is the largest city within California’s Central Coast, and is the Monterey County government seat. Within its approximately 14,400 acres, the City has become a residential, suburban community within an agricultural setting. The City’s population is now a growing 153, 215 people.2 Salinas is also Monterey County’s workforce center, supporting approximately one-third of all jobs within Monterey County. In 2012, agricultural production within Monterey County accounted for nearly $4.14 billion in sales.3 Agricultural production, and the City’s economy and quality of life, rely upon a steady supply of clean water. Waterways in the Salinas Valley are conjunctive, that is, surface water flows recharge groundwater. Groundwater supplies most of the region’s water. Runoff from the Gabilan and Santa Lucia Mountain Ranges are tributary to Salinas River flows. Runoff from local mountains, farms and developed areas can carry with it more than merely water. Runoff can also carry a mix of pollutants. This chapter provides a brief summary of hydrologic conditions within the City of Salinas and nearby watersheds. 1 1950 2 State Department of Finance, May 2013. 3 County of Monterey Agricultural Commissioner’s Office, Monterey County Crop Report, 2012. ______________________________________________________________________ 277 Stormwater Management Plan ______________________________________________________________________ Q.2 Hydrology The River itself has no beginning or end. -

Pinnacles National Park Plan

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Business Management Group Pinnacles National Park 2014 Business Plan Produced by National Park Service Business Management Group U.S. Department of the Interior Washington, DC Spring 2014 California condors warm themselves by basking in the sun. National Park Service Mission: The National Park Service preserves unimpaired the natural and cultural resources and intrinsic values of the national park system for the enjoyment, education, and inspiration of this and future generations. The National Park Service cooperates with partners to extend the benefits of natural and cultural resource conservation and outdoor recreation throughout this country and the world. Table of Contents 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS 2 INTRODUCTION 2 Letter from the Superintendent 3 Business Planning at the National Park Service 4 Executive Summary 6 PARK OVERVIEW 6 Park Orientation 7 History and Enabling Legislation 8 Resources 9 Visitation 10 Personnel 12 Employee and Visitor Safety 14 Volunteers 15 Park Networks and Shared Services 16 Partnerships and Cooperating Organizations 17 The Condor Recovery Program 18 STRATEGIC GOALS 18 Strategic Goals 20 FINANCIAL OVERVIEW 20 Funding Sources and Expenditures 22 Division Allocations 23 DIVISION OVERVIEWS 23 Research and Resource Management 26 Management and Administration 28 Facility Operations and Maintenance 30 Interpretation and Education 32 Visitor and Resource Protection 34 FINANCIAL PROJECTIONS AND STRATEGIC PLANNING 34 Appropriated Base Budget Scenarios 36 Primary Cost Drivers 37 Strategies for Cost Reduction and Operational Efficiency 39 Strategies for Increasing Funding and Capacity 40 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS 40 Acknowledgments From top: A non-native European honeybee visits 41 Stay Connected with Pinnacles National Park milkweed flowers; Bear Gulch Reservoir provides year-round water for many wildlife species; the pig fence requires regular monitoring and maintenance. -

CENTRAL COASTAL PROVINCE (011) by Richard G

CENTRAL COASTAL PROVINCE (011) by Richard G. Stanley With a section on the Cuyama Basin by M.E. Tennyson INTRODUCTION Province 11 includes much of central coastal California from Point Arena southward to the western Transverse Ranges (but does not include the Santa Maria Province, which is being assessed separately). Province 11 is bounded on the east by the San Andreas Fault, on the south by the Big Pine Fault, on the southwest by the Sur-Nacimiento Fault, and on the west by the 3-mi limit offshore. The province is about 390 mi long from northwest to southeast, about 40 mi wide at its widest near Soledad, California, and occupies an area of about 8,000 sq mi. The main petroleum exploration objectives in Province 11 are in moderately deformed Tertiary sedimentary rocks, which locally exhibit a composite thickness of more than about 48,000 ft. Upper Cretaceous sedimentary rocks as thick as 13,000 ft are present locally but are believed to have poor petroleum potential. Over most of the province, the Tertiary and Upper Cretaceous sedimentary rocks overlie Cretaceous and older granitic and metamorphic rocks of the Salinia terrane. However, parts of the Santa Cruz Mountains are underlain by rocks of the Franciscan assemblage, and a small coastal area near Point Arena, California, appears to be underlain by unnamed and undated spilite that may represent a fragment of Mesozoic oceanic crust. The earliest drilling operations in Province 11, exclusive of the Cuyama Basin, apparently occurred about 1867 near surface oil seeps in the Half Moon Bay, California area. -

4.9 Hydrology and Water Quality

Del Webb at San Juan Oaks Specific Plan Subsequent EIR Section 4.9 Hydrology and Water Quality 4.9 HYDROLOGY AND WATER QUALITY 4.9.1 Setting a. Hydrology. Regional Hydrology. The Project Site overlies the San Juan Subbasin (Subbasin), which is a subbasin of the larger Gilroy-Hollister Groundwater Basin (Tully & Young, May 2015). The boundaries of the Subbasin have been delineated by the California Department of Water Resources (DWR) and the San Benito County Water District (SBCWD). Although DWR’s and SBCWD’s boundaries differ slightly [See Appendix J (Water Supply Assessment (WSA), Fig. 3- 1], the Project Site lies within both the DWR and the SBCWD boundaries for the Subbasin. For the reasons described in the WSA (Appendix J), this SEIR relies on the SBCWD’s delineation because the SBCWD has consistently used this boundary for planning, data compilation, and water resources management since 1996. In addition, the SBCWD collects groundwater and surface water use, groundwater level, and water quality data and uses this Subbasin boundary as the basis for annual groundwater reporting. The Gilroy-Hollister Valley Groundwater Basin is located within the Coast Ranges Geomorphic Province of California. The Coast Ranges Geomorphic Province is comprised of a series of northwest-southeast trending ranges and valleys sub-parallel to the San Andreas Fault Zone. The origin and shape of the Gilroy-Hollister Valley Groundwater Basin is controlled by the folding and faulting of basement rocks in the region, which have resulted in low-lying areas filled with unconsolidated to poorly consolidated alluvium of Tertiary and Quaternary age.