Football Fans As an Example of a Community Beyond the Government’S Control in the Conditions of the Authoritarian Regime

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Results 07/10/2017 Page 1

Results 07/10/2017 Page 1 ABA LEAGUE AUSTRALIA NBL 17:00 3029 Mega Bemax Mornar 41 : 32 91 : 70 8:30 3004 Sydney Adelaide 50 : 46 96 : 105 19:00 3030 Partizan FMP Beograd 45 : 43 87 : 84 11:30 3034 Perth Brisbane Bullets 49 : 39 96 : 86 ARGENTINA 2 AUSTRIA 3 - CENTRAL 20:05 525 Quilmes Los Andes 1 : 0 1 : 0 16:00 114 Union Gurten Stadl Paura 0:0 0:0 20:30 526 Brown Adrogue Agropecuario 3:0 3:1 AUSTRIA 3 - EAST 21:00 527 Aldosivi Almagro 0:0 1:3 21:30 528 Ferro Gualeguaychu JU 0 : 0 0 : 1 16:00 118 First Vienna Ebreichsdorf 0:1 1:1 23:00 529 All Boys San Martin T. 1 : 0 1 : 1 16:00 119 Karabakh Wien Admira (Am) 1:1 2:1 16:00 120 Traiskirchen Wiener SC 0:1 1:1 ARGENTINA 3 17:00 121 Mannsdorf Austria W.(Am) 1:1 1:2 18:05 530 Platense Fenix. 3:0 4:0 AUSTRIA 3 - WEST 18:15 531 Barracas Colegiales 1:1 1:2 20:30 532 Acassuso UAI Urquiza 0 : 0 0 : 1 15:30 126 Alberschwende USK Anif 0:1 0:2 20:30 533 Def. Belgrano Comunicaciones 0 : 0 1 : 2 16:00 127 Dornbirn Saalfelden 0:1 0:1 20:30 534 Estudiantes CA Dep. Espanol 1 : 0 1 : 0 16:00 128 Grodig Altach (Am) 1:0 3:0 16:00 129 Hard Johann 3:4 4:4 ARGENTINA CUP AUSTRIA EBEL 1:30 101 Huracan Velez 0:0 0:0 19:15 4079 Vienna Capitals Dornbirn 0:0 2:0 ARGENTINA TORNEO SUPER 20 AUSTRIA HLA 3:00 3001 La Union Estudiantes 44 : 28 79 : 70 3:00 3002 Weber Bahia Argentino 43 : 44 85 : 75 18:00 5010 Aon Fivers Bruck 13 : 8 30 : 23 18:00 5011 Schwaz Alpla Hard 14 : 12 24 : 29 ATP BEIJING, CHINA 19:00 5012 HSG Graz Krems 17 : 13 30 : 31 10:30 2017 Nadal R. -

Weekend Regular Coupon 21/03/2020 10:07 1 / 3

Issued Date Page WEEKEND REGULAR COUPON 21/03/2020 10:07 1 / 3 BOTH TEAMS INFORMATION 3-WAY ODDS (1X2) DOUBLE CHANCE TOTALS 2.5 1ST HALF - 3-WAY HT/FT TO SCORE HANDICAP (1X2) GAME CODE HOME TEAM 1 / 2 AWAY TEAM 1/ 12 /2 2.5- 2.5+ 01 0/ 02 1-1 /-1 2-1 1-/ /-/ 2-/ 2-2 /-2 1-2 ++ -- No CAT TIME DET NS L 1 X 2 1X 12 X2 U O 1 X 2 1/1 X/1 2/1 1/X X/X 2/X 2/2 X/2 1/2 YES NO HC 1 X 2 Saturday, 21 March, 2020 6030 AU 10:30 1 L WESTERN SYDNEY 8 3.55 3.45 1.90 1 SYDNEY FC 1.75 1.24 1.23 2.00 1.70 3.95 2.20 2.40 6.40 8.30 33.0 14.5 5.80 14.0 2.95 4.90 23.0 1.60 2.10 1:0 1.80 3.80 3.20 6031 AUS4 11:00 FORRESTFIELD UNITED.. - - - UWA NEDLANDS FC - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - 6192 RUS4 11:00 MYASNIKYANA CHALTYR - - - FC AHLAMOV-UOR - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - 6207 HUN19 11:00 VASAS - - - MTK HUNGARIA - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - 6229 INFR 11:00 3 ESLOVS BK 1.50 4.70 4.60 HOGABORGS BK 1.14 1.13 2.32 3.65 1.24 1.85 2.75 4.30 2.15 4.70 18.0 14.5 10.0 15.0 7.90 12.5 34.0 1.33 2.90 0:1 2.10 4.20 2.35 6230 INFR 11:00 FC ZORKIJ KRASNOGOR. -

Midweek Regular Coupon 25/03/2020 09:28 1 / 1

Issued Date Page MIDWEEK REGULAR COUPON 25/03/2020 09:28 1 / 1 BOTH TEAMS INFORMATION 3-WAY ODDS (1X2) DOUBLE CHANCE TOTALS 2.5 1ST HALF - 3-WAY HT/FT TO SCORE HANDICAP (1X2) GAME CODE HOME TEAM 1 / 2 AWAY TEAM 1/ 12 /2 2.5- 2.5+ 01 0/ 02 1-1 /-1 2-1 1-/ /-/ 2-/ 2-2 /-2 1-2 ++ -- No CAT TIME DET NS L 1 X 2 1X 12 X2 U O 1 X 2 1/1 X/1 2/1 1/X X/X 2/X 2/2 X/2 1/2 YES NO HC 1 X 2 Friday, 27 March, 2020 5016 BELR 11:30 L FC GORODEYA - - - SHAKHTYOR SOLIGORSK - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - 5017 INFR 12:00 L FC ZENIT MOSCOW - - - FK KRASKOVO - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - 5018 BELR 13:00 L FC MINSK - - - DINAMO MINSK - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - 5002 ISR3 13:00 HAPOEL MIGDAL HAEMEK - - - HAPOEL KAFR KANNA - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - 5019 ISR3S 13:00 HAPOEL HOD HASHARON - - - SHIMSHON BNEI TAIBE - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - 5020 ISR3S 13:00 BEITAR IRONI KIRYAT GAT - - - IRONI MODIIN - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - 5014 BUR 13:30 3 L RUKINZO FC 3.75 3.15 1.95 MUSONGATI FC 1.71 1.28 1.20 1.55 2.35 - - - - - - - - - - - - 2.05 1.65 1:0 1.75 3.45 3.70 5004 INFR 16:00 DJURGARDENS IF - - - GIF SUNDSVALL - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - 5015 BUR 16:00 3 L AS INTER STAR 1.95 3.25 3.60 NGOZI CITY FC 1.22 1.26 1.71 1.65 2.15 - - - - - - - - - - - - 1.90 1.75 0:1 3.60 3.50 1.75 5012 BLS 17:00 3 L TORPEDO-BELAZ 4 1.60 3.65 5.10 14 FC BELSHINA BOBRUISK 1.11 1.22 2.13 1.80 1.90 2.15 2.15 5.30 2.45 4.10 23.0 15.5 5.70 17.0 10.3 10.8 43.0 1.90 1.75 0:1 2.60 3.45 2.15 5005 INFR 18:00 IFK GOTEBORG - - - DEGERFORS IF - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - 5013 BLS 19:00 3 L FC RUH BREST 4 2.55 3.40 2.40 1 FC ZVEZDA-BGU MINSK 1.46 1.24 1.41 2.05 1.70 3.05 2.15 2.95 4.30 6.30 27.0 13.5 5.70 13.5 4.00 6.00 26.0 1.55 2.20 1:0 1.45 4.20 4.50 5009 VEN2 21:00 ATLETICO FURRIAL - - - ESTUDIANTES DE CARA. -

Betus.Com.Pa 1-888-51-Betus

MAY 1ST MAY 2ND BASEBALL BASEBALL INT - TAIWAN CPBL INT - TAIWAN CPBL 10:05 PM Chinatrust Brothers Rakuten Monkeys 10:05 PM Chinatrust Brothers Rakuten Monkeys 10:05 PM Fubon Guardians Uni Lions 10:05 PM Fubon Guardians Uni Lions INT - TAIWAN CPBL 2ND LEAGUE OTHER SPORTS 1:00 AM Rakuten Monkeys 2 Uni-Lions 2 ESPORTS - DOTA2 CHINA PROFESSIONAL LEAGUE OTHER SPORTS 4:00 AM Invictus Gaming CDEC Gaming ESPORTS - DOTA2 CHINA PROFESSIONAL LEAGUE 7:00 AM Newbee Sparking Arrow Gaming 4:00 AM Vici Gaming CDEC Gaming ESPORTS - LOL PCS SPRING PLAYOFFS 7:00 AM Keen Gaming Sparking Arrow Gaming 3:00 AM ahq eSports Club Hong Kong Attitude DARTS - PDC HOME TOUR 2020 DARTS - PDC HOME TOUR 2020 2:30 PM Darren Webster Bradley Brooks 2:30 PM Ricky Evans Martin Atkins 3:00 PM Scott Baker Andy Hamilton 3:00 PM Christian Bunse Jeff Smith 3:30 PM Bradley Brooks Andy Hamilton 3:30 PM Martin Atkins Jeff Smith 4:00 PM Darren Webster Scott Baker 4:00 PM Ricky Evans Christian Bunse 5:00 PM Scott Baker Bradley Books 4:30 PM Christian Bunse Martin Atkins 5:30 PM Andy Hamilton Darren Webster 5:00 PM Jeff Smith Ricky Evans ESPORTS - LOL EUROPEAN MASTERS SPRING ESPORTS - LOL LPL SPRING PLAYOFFS 12:30 PM K1CK Neosurf Movistar Riders 5:00 AM Top Esports JD Gaming 1:30 PM Schalke 04.Evo Movistar Riders ESPORTS - LOL EUROPEAN MASTERS SPRING 3:30 PM Schalke 04.Evo K1CK Neosurf 11:30 AM mousesports Energypot Wizards ESPORTS - CS GO ELISA INVITATIONAL 12:30 PM Fnatic Rising eSuba 6:00 AM Nordavind KOVA 1:30 PM Fnatic Rising mousesports 7:30 AM North Heroic 2:30 PM eSuba Energypot -

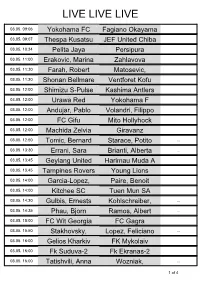

Live Live Live

LIVE LIVE LIVE 03.05. 09:06 Yokohama FC Fagiano Okayama 03.05. 09:07 Thespa Kusatsu JEF United Chiba 03.05. 10:34 Pelita Jaya Persipura 03.05. 11:00 Erakovic, Marina Zahlavova 03.05. 11:30 Farah, Robert Matosevic, 03.05. 11:30 Shonan Bellmare Ventforet Kofu 03.05. 12:00 Shimizu S-Pulse Kashima Antlers 03.05. 12:00 Urawa Red Yokohama F 03.05. 12:00 Andujar, Pablo Volandri, Filippo 03.05. 12:00 FC Gifu Mito Hollyhock 03.05. 12:00 Machida Zelvia Giravanz 03.05. 12:50 Tomic, Bernard Starace, Potito ... 03.05. 13:30 Errani, Sara Brianti, Alberta ... 03.05. 13:45 Geylang United Harimau Muda A 03.05. 13:45 Tampines Rovers Young Lions 03.05. 14:00 Garcia-Lopez, Paire, Benoit 03.05. 14:00 Kitchee SC Tuen Mun SA 03.05. 14:30 Gulbis, Ernests Kohlschreiber, ... 03.05. 14:35 Phau, Bjorn Ramos, Albert ... 03.05. 15:00 FC Wit Georgia FC Gagra 03.05. 15:50 Stakhovsky, Lopez, Feliciano ... 03.05. 16:00 Gelios Kharkiv FK Mykolaiv 03.05. 16:00 Fk Suduva-2 Fk Ekranas-2 03.05. 16:00 Tatishvili, Anna Wozniak, ... 1 of 4 03.05. 16:00 Hanescu, Victor Rosol, Lukas 03.05. 16:00 Mordovya Alania ... 03.05. 16:00 Krymteplitsya Dinamo-2 Kiev 03.05. 16:30 FC Naftan FC Brest 03.05. 16:30 Torpedo-Belaz FC BATE Borisov 03.05. 16:30 FC Shinnik FC Torpedo 03.05. 16:30 FC Slavia Mozyr FC Minsk 03.05. 17:00 FC Kryliya FC Tom Tomsk 03.05. -

Midweek Regular Coupon 07/06/2021 11:45 1 / 1

Issue Date Page MIDWEEK REGULAR COUPON 07/06/2021 11:45 1 / 1 BOTH TEAMS INFORMATION 3-WAY ODDS (1X2) DOUBLE CHANCE TOTALS 2.5 1ST HALF - 3-WAY HT/FT TO SCORE HANDICAP (1X2) GAME CODE HOME TEAM 1 / 2 AWAY TEAM 1/ 12 /2 2.5- 2.5+ 01 0/ 02 1-1 /-1 2-1 1-/ /-/ 2-/ 2-2 /-2 1-2 ++ -- No CAT TIME DET NS L 1 X 2 1X 12 X2 U O 1 X 2 1/1 X/1 2/1 1/X X/X 2/X 2/2 X/2 1/2 YES NO HC 1 X 2 Friday, 11 June, 2021 5001 AFCF 10:00 L MYANMAR 4 - - - 3 KYRGYZSTAN - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - 5002 AUV 13:00 L GREEN GULLY CAVALIERS 9 - - - 1 AVONDALE FC - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - 5003 INF 13:25 JAPAN - - - SERBIA - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - 5004 AFCA 17:00 L PHILIPPINES 3 - - - 5 GUAM - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - 5005 AFCC 17:30 L CAMBODIA 5 - - - 3 IRAN - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - 5008 LIT 18:00 L FK SUDUVA (LIT) 1 - - - 3 ZALGIRIS V. (LTU) - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - 5007 FIN3 18:00 HJS AKATEMIA 7 - - - 6 TAMPERE - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - 5006 BLS 18:00 FC SLAVIA MOZYR 13 - - - 10 FC MINSK - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - 5009 FIN1 18:30 1 L AC OULU 12 3.90 3.10 1.90 11 HONKA 1.73 1.29 1.19 1.60 2.20 4.60 2.00 2.60 7.20 8.80 35.0 16.5 4.60 15.5 3.10 4.80 33.0 1.95 1.70 1:0 1.75 3.50 3.50 5039 INFW 18:30 L ITALY (W) - - - NETHERLANDS (W) - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - 5040 INFW 19:00 L FINLAND (W) - - - POLAND (W) - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - 5041 INFW 19:00 L ICELAND (W) - - - IRELAND (W) -

Uefa Europa League

UEFA EUROPA LEAGUE - 2014/15 SEASON MATCH PRESS KITS Stadio Artemio Franchi - Florence Thursday 11 December 2014 21.05CET (21.05 local time) ACF Fiorentina Group K - Matchday 6 FC Dinamo Minsk Last updated 09/06/2015 19:04CET Previous meetings 2 Match background 3 Team facts 4 Squad list 6 Fixtures and results 8 Match-by-match lineups 12 Match officials 14 Legend 15 1 ACF Fiorentina - FC Dinamo Minsk Thursday 11 December 2014 - 21.05CET (21.05 local time) Match press kit Stadio Artemio Franchi, Florence Previous meetings Head to Head UEFA Europa League Date Stage Match Result Venue Goalscorers FC Dinamo Minsk - ACF Aquilani 33, Iličić 62, 02/10/2014 GS 0-3 Borisov Fiorentina Bernardeschi 67 Home Away Final Total Pld W D L Pld W D L Pld W D L Pld W D L GF GA ACF Fiorentina 0 0 0 0 1 1 0 0 0 0 0 0 1 1 0 0 3 0 FC Dinamo Minsk 1 0 0 1 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 1 0 0 1 0 3 ACF Fiorentina - Record versus clubs from opponents' country ACF Fiorentina have not played against a club from their opponents' country FC Dinamo Minsk - Record versus clubs from opponents' country UEFA Cup Date Stage Match Result Venue Goalscorers Ostrovski 45 (og), 4-1 27/09/1994 R1 SS Lazio - FC Dinamo Minsk Rome Favalli 61, Bokšić 74, agg: 4-1 Fuser 83; Kachuro 9 13/09/1994 R1 FC Dinamo Minsk - SS Lazio 0-0 Minsk Home Away Final Total Pld W D L Pld W D L Pld W D L Pld W D L GF GA ACF Fiorentina 0 0 0 0 1 1 0 0 0 0 0 0 1 1 0 0 3 0 FC Dinamo Minsk 2 0 1 1 1 0 0 1 0 0 0 0 3 0 1 2 1 7 2 ACF Fiorentina - FC Dinamo Minsk Thursday 11 December 2014 - 21.05CET (21.05 local time) Match press kit Stadio Artemio Franchi, Florence Match background ACF Fiorentina will look to extend their unbeaten run in the UEFA Europa League as they take on FC Dinamo Minsk, who are destined to finish bottom of Group K. -

FC BATE Borisov - Real Madrid CF MATCH PRESS KIT Dinamo, Minsk Tuesday 25 November 2008 - 20.45CET Group H - Matchday 5

FC BATE Borisov - Real Madrid CF MATCH PRESS KIT Dinamo, Minsk Tuesday 25 November 2008 - 20.45CET Group H - Matchday 5 Contents 1 - Match background 7 - UEFA information 2 - Match facts 8 - Match-by-match lineups 3 - Squad list 9 - Competition facts 4 - Head coach 10 - Team facts 5 - Match officials 11 - Legend 6 - Domestic information This press kit includes information relating to this UEFA Champions League match. For more detailed factual information, and in-depth competition statistics, please refer to the matchweek press kit, which can be downloaded at: http://www.uefa.com/uefa/mediaservices/presskits/index.html Match background Home-and-away defeats against Juventus have jolted Real Madrid CF's confidence in their UEFA Champions League campaign but they still lie in second place in Group H and will be hoping to get back on an even keel when they travel to face FC BATE Borisov, who lie at the foot of the section with just two points. • While BATE were denied in their quest for a first UEFA Champions League victory when they lost at home to FC Zenit St. Petersburg on Matchday 4, Madrid's hopes of gaining revenge on Juventus also came unstuck on home soil. Having gone down to the Italian giants two weeks previously, Los Merengues knew they would have their work cut out in the return but it was still a huge disappointment to be on the wrong end of a 2-0 defeat. A superb goal in each half from Juventus captain Alessandro Del Piero secured a place in the first knockout round for the Turin side with two matches to spare. -

Uefa Champions League 2012/13 Season Match Press Kit

UEFA CHAMPIONS LEAGUE 2012/13 SEASON MATCH PRESS KIT FC BATE Borisov LOSC Lille Group F - Matchday 5 Dinamo Stadion, Minsk Tuesday 20 November 2012 18.00CET (20.00 local time) Contents Previous meetings.............................................................................................................2 Match background.............................................................................................................3 Match facts........................................................................................................................4 Squad list...........................................................................................................................5 Head coach.......................................................................................................................7 Match officials....................................................................................................................8 Fixtures and results...........................................................................................................9 Match-by-match lineups..................................................................................................13 Group Standings.............................................................................................................15 Competition facts.............................................................................................................17 Team facts.......................................................................................................................18 -

Midweek Regular Coupon 28/06/2021 11:35 1 / 2

Issue Date Page MIDWEEK REGULAR COUPON 28/06/2021 11:35 1 / 2 BOTH TEAMS INFORMATION 3-WAY ODDS (1X2) DOUBLE CHANCE TOTALS 2.5 1ST HALF - 3-WAY HT/FT TO SCORE HANDICAP (1X2) GAME CODE HOME TEAM 1 / 2 AWAY TEAM 1/ 12 /2 2.5- 2.5+ 01 0/ 02 1-1 /-1 2-1 1-/ /-/ 2-/ 2-2 /-2 1-2 ++ -- No CAT TIME DET NS L 1 X 2 1X 12 X2 U O 1 X 2 1/1 X/1 2/1 1/X X/X 2/X 2/2 X/2 1/2 YES NO HC 1 X 2 Friday, 02 July, 2021 5058 AUG 12:00 L MUSGRAVE - - - RUNAWAY BAY BAYHAWK.. - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - 5002 AUNSW 12:00 L MANLY UNITED FC 4 - - - 10 NORTH SHORE MARINER.. - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - 5059 BELR 12:00 ENERGETIK BGU MINSK R.. - - - FC ISLOCH RESERVES - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - 5001 ACH 12:00 L PERSIPURA JAYAPURA - - - HOME UNITED FC - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - 5004 AUV 13:00 GREEN GULLY CAVALIERS 10 - - - 12 ALTONA MAGIC SC - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - 5005 CHN 13:00 L SHIJIAZHUANG EVER BRI.. 7 - - - 5 QINGDAO HAINIU - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - 5003 ACLF 13:00 L KAYA FC - - - 1 ULSAN HYUNDAI - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - 5006 AUV 13:30 L OAKLEIGH CANNONS 2 - - - 13 DANDENONG CITY SC - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - 5007 BANG 14:00 SHEIKH JAMAL 3 - - - 6 SAIF SC - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - 5060 BANG 14:00 SHEIKH RUSSEL KC 7 - - - 3 SHEIKH JAMAL - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - 5009 CHN 15:00 L SHENZHEN HONZUAN 2 - - - 8 FC HENAN JIANYE - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - 5008 -

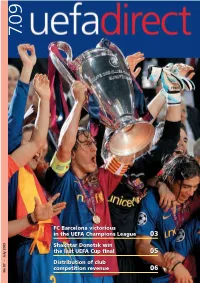

Uefadirect #87 (07.2009)

UEFAdirect-87-Fichier•E 15.6.2009 9:56 Page 1 7.0 9 FC Barcelona victorious in the UEFA Champions League 03 Shakhtar Donetsk win the last UEFA Cup final 05 Distribution of club competition revenue 06 No 58 – Février 2007 87 July 2009 UEFAdirect-87-Fichier•E 15.6.2009 9:56 Page 2 Message Photos: UEFA-pjwoods.ch of the president When the party goes without a hitch When the action of the teams on the pitch overshadows that of the police behind the scenes, when control of the ball eclipses that of spectators at the turnstiles, when the sun shines, the stadium is full, the crowd bright and cheerful, and the facilities magnificent, you have all the ingredients for a successful celebration. You also need the cast of the show – the players and match officials – and its directors – the coaches – to live up to expectations, which are inevitably high where the climax of the European club competition season is concerned. I was really pleased with the UEFA Champions League final in Rome’s Olympic Stadium in May. The match was action-packed from the start, and it was not long before its first highlight: Samuel Eto’o’s goal, scored at the end of FC Barcelona’s first attack following an opening period in which they had been constantly on the back foot. The Catalans then showed that technical brilliance IN THIS ISSUE at keeping and moving the ball was a much more elegant and certainly no less FC Barcelona efficient way of overpowering an opponent than out-and-out defence. -

Stadium Attendance Demand During the COVID-19 Crisis: Early Empirical Evidence from Belarus by J

gareth.jones Section nameDepartment of Economics Sport Economics Cluster Football Research Group Economic Analysis Research Group (EARG) Stadium attendance demand during the COVID-19 crisis: Early empirical evidence from Belarus by J. James Reade, Dominik Schreyer and Carl Singleton Discussion Paper No. 2020-20 Department of Economics University of Reading Whiteknights Reading RG6 6AA United Kingdom www.reading.ac.uk © Department of Economics, University of Reading 2020 Stadium attendance demand during the COVID-19 crisis: Early empirical evidence from Belarus J. James Reade, a Dominik Schreyer, b,* and Carl Singleton a a Department of Economics, University of Reading, Whiteknights Campus, RG6 6UA, United Kingdom b Center for Sports and Management (CSM), WHU - Otto Beisheim School of Management, Erkrather Str. 224a, 40233, Düsseldorf, Germany * Corresponding author. E-Mail: [email protected]. First Version: July 14, 2020 Current Version: September 25, 2020 Forthcoming in Applied Economics Letters Abstract In this note, we consider early evidence regarding behavioural responses to an emerging public health emergency. We explore patterns in stadium attendance demand by exploiting match-level data from the Belarusian Premier League (BPL), a football competition that kept playing unrestricted in front of spectators throughout the global COVID-19 pandemic, unlike all other European professional sports leagues. We observe that stadium attendance demand in Belarus declined significantly in the initial period of maximum uncertainty. Surprisingly, demand then slowly recovered, despite the ongoing inherent risk to individuals from going to a match. Keywords: attendance; COVID-19; football/soccer; spectator decision-making; public health JEL: D12; D81; D90; H12; I18; L83; Z20 Acknowledgements: We would like to thank two anonymous reviewers for helpful discussions and comments on the manuscript.