Migration Trends in Selected Applicant Countries”, the Following Volumes Are Available

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sakrop04.Pdf

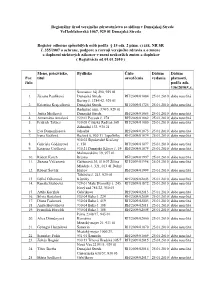

Regionálny úrad verejného zdravotníctva so sídlom v Dunajskej Strede Ve ľkoblahovská 1067, 929 01 Dunajská Streda Register odborne spôsobilých osôb pod ľa § 15 ods. 2 písm. c) zák. NR SR č. 355/2007 o ochrane, podpore a rozvoji verejného zdravia a o zmene a doplnení niektorých zákonov v znení neskorších zmien a doplnkov ( Registrácia od 01.01.2010 ) Meno, priezvisko, Bydlisko Číslo Dátum Dátum Por. titul osved čenia vydania platnosti, číslo pod ľa zák. 136/2010Z.z. Smetanov háj 290, 929 01 1. Zuzana Paulíková Dunajská Streda RH/2009/01084 25.01.2010 doba neur čitá Boriny č. 1384/42, 929 01 2. Krisztína Krajcsiková Dunajská Streda RH/2009/01725 25.01.2010 doba neur čitá Radni čné nám. 374/5, 929 01 3. Judita Misáková Dunajská Streda RH/2009/01085 25.01.2010 doba neur čitá 4. Annamária Antalová 929 01 Povoda č. 278 RH/2009/01082 25.01.2010 doba neur čitá 5. Fridrich Takács 930 08 Čilizská Radva ň 368 RH/2009/01080 25.01.2010 doba neur čitá Záhradná 133, 930 21 6. Eva Domonkosová Jahodná RH/2009/01075 25.01.2010 doba neurčitá 7. Irena Gaálová Ružová 6, 930 11 Topo ľníky RH/2009/01074 25.01.2010 doba neur čitá 930 03 Šipošovské Kra čany 8. Gabriela Gódányová č. 150 RH/2009/01077 25.01.2010 doba neur čitá 9. Katarína Csölleová 930 21 Dunajský Klátov č. 19 RH/2009/01079 25.01.2010 doba neur čitá Malinovského 19, 977 01 10. Róbert Kore ň Brezno RH/2009/01997 25.01.2010 doba neur čitá 11. -

SOMORJA VÁROS Mestský Úrad - Városi Hivatal Hlavná 37 - Fő Utca 37 931 01 Šamorín - 931 01 Somorja

MESTO ŠAMORÍN - SOMORJA VÁROS Mestský úrad - Városi hivatal Hlavná 37 - Fő utca 37 931 01 Šamorín - 931 01 Somorja SPOLOČNÁ DEKLARÁCIA MIEST A OBCÍ – RÚSES DS V súvislosti s oznámením o začatí konania vo veci zámeru schválenia dokumentu regionálneho územného systému ekologickej stability okresu Dunajská Streda (RÚSES) Vám zasielame spoločnú deklaráciu nižšie uvedených obcí s cieľom upozorniť spracovateľa a obstarávateľa dokumentu na všeobecne známe ekologické problémy týkajúce sa nášho okresu. Zároveň Vás spoločne žiadame, aby ste v záujme zlepšenia súčasného stavu ekológie okresu Dunajská Streda, akceptovali naše požiadavky uvedené v tejto spoločnej deklarácií. My, dolu uvedení/é primátori/ky a starostovia/ky , touto formou deklarujeme nasledovný spoločný názor (stanovisko) k pripravovanému dokumentu RÚSES Dunajská Streda: Výsledný koeficientov stability celého okresu Dunajská Streda výrazne zdeformuje skutočnosť, že spracovateľ dokumentu pri stanovení vplyvov vodného diela Gabčíkovo na ekológiu krajiny počítal iba s pozitívnymi vplyvmi a nezohľadnil jeho negatívne stresové faktory, ktorými sú: • intenzívna medzinárodná lodná doprava a cyklistická cesta Eurovelo 6, • úseky brehu, ktoré sa intenzívne využívajú na oddych a rekreáciu, • neprírodný, strmý breh hrádze nevhodný pre vodných živočíchov a rastlín, • regulácia Dunaja výstavbou vodného diela spôsobila zníženie hladiny a dynamiky podzemných vôd vo vnútorných územiach okresu. Tieto javy viedli k definitívnemu vysychaniu mokradí a zazemnených ramien Dunaja v poľnohospodárskej krajine -

20171129Register Potraviny Rok 2017

Regionálny úrad verejného zdravotníctva so sídlom v Dunajskej Strede Ve ľkoblahovská 1067, 929 01 Dunajská Streda Register odborne spôsobilých osôb pod ľa § 15 ods. 2 písm. c) zák. NR SR č. 355/2007 o ochrane, podpore a rozvoji verejného zdravia a o zmene a doplnení niektorých zákonov v znení neskorších zmien a doplnkov ( Registrácia od 01.01.2017) Meno, priezvisko, Bydlisko Číslo osved čenia Dátum Dátum Por. titul vydania platnosti, číslo pod ľa zák. 136/2010Z.z. Nemesszegská 133/12, RH/2017/00169/004- 1. Ľudovíth P őthe 929 01 Dunajská Streda BI 16.01.2017 doba neur čitá RH/2017/00148/004- 2. Ján Janík 930 04 Baka č. 110 BI 16.01.2017 doba neur čitá Malá ulica 244/20, 929 01 RH/2017/00170/004- 3. Gabriela P őtheová Malé Dvorníky BI 16.01.2017 doba neur čitá Kuku čínova 1213/5, 929 RH/2017/00166/004- 4. Gy őrgy Nagy 01 Dunajská Streda BI 16.01.2017 doba neur čitá Dunajská 371/9, 929 01 RH/2017/00154/004- 5. Olivér Ábrahám Dunajská Streda BI 16.01.2017 doba neur čitá Bihariho 522/10, 929 01 RH/2017/00167/004- 6. Juraj Pavlík, Ing. Dunajská Streda BI 16.01.2017 doba neur čitá Hortobá ďska ulica RH/2017/00159/004- 7. Marian Horváth 158/106, 930 12 Ohrady BI 16.01.2017 doba neur čitá Záhradnícka ulica 561/38, RH/2017/00161/004- 8. Erik Kardos 930 10 Dolný Štál BI 16.01.2017 doba neur čitá Nám. SNP 189/16, 929 01 RH/2017/00168/004- 9. -

201802Mesiac Február 2018

REGIONÁLNY ÚRAD VEREJNÉHO ZDRAVOTNÍCTVA so sídlom v Dunajskej Strede Veľkoblahovská 1067, 92901 Dunajská Streda _______________________________________________________________________ Číslo:RH/2018/001980/BM7 Dunajská Streda 1.3.2018 Podľa rozdeľovníka Vec: Mesačný výkaz prenosných ochorení za mesiac február 2018 za okres Dunajská Streda Ochorenie Počet Miesto ochorenia Salmonelóza 11 Dunajská Streda – 1, Gabčíkovo – 1, A02.0 Horná Potôň – 1, Kútniky – 1, Ohrady – 1, Rohovce - 2, Veľké Blahovo – 1,Veľký Meder 3 Iné bakteriálne črevné infekcie 28 Čakany – 1 ,Čiližská Radvaň – 1, A04.5,A04.6, A04.7, A04.8 Dunajská Streda – 11, Gabčíkovo – 1, Horná Potôň – 1, Jahodná -2, Kútniky – 1, Kvetoslavov -1, Mierovo -1, Ohrady- 1, Povoda -1, Rohovce -1, Štvrtok na Ostrove – 1, Topoľníky – 1, Veľký Meder - 3 Vírusové enteritídy 1 Gabčíkovo – 1 A08.2 Hnačka a gastroenteritída 35 Dunajská Streda - 35 pravdepodobne infekčného pôvodu A09 Gonokokové inf.dolných častí 3 Dunajská Streda – 2, močovopohl.sústavy Lúč na Ostrove - 1 A54.0 Chlamýdiové infekcie dolných 2 Dunajská Streda – 1, Šamorín - 1 častí močovopohlavnej sústavy A56.0 Urogenitálna trichomonóza 2 Dunajská streda – 1, Gabčíkovo - 1 A59.0 Varicella 34 Dolný Štál – 2, B01.9 Dunajská Streda – 10, Holice – 1, Jahodná – 1, Nový Život – 2, Ohrady – 2, Okoč – 3, Šamorín – 2, Veľké Blahovo - 2, Veľký Meder – 2, Zlaté Klasy - 7 Chronická vírusová hepatitída C 1 Dunajská Streda - 1 B18.2 Iná infekčná mononukleóza 2 Dunajská Streda – 1, B27.8 Veľké Dvorníky - 1 - 2 - Svrab – scabies 3 Dunajská Streda – 1, Dolný Štál - 2 B86 Chrípka vyvolaná 33 Dunajská Streda -8, identifikovaným vírusom chrípky Gabčíkovo – 1, Horná Potôň – 1, J10 Kostoľné Kračany – 1, Okoč – 1, Povoda – 3, Rohovce – 1, Topoľníky - 1, Veľký Meder - 16 Chlamýdiová pneumonia 8 Veľké Dvorníky – 1, Veľký Meder - 7 J10.6 Nozokomiálne nákazy 11 Dunajská Streda – 11 A04.7, N39.0, T81.4 Kontakt alebo ohrozenie 3 Dunajská Streda - 1, Šamorín – 1, besnotou Veľké Dvorníky - 1 Z20.3 I. -

Kameno-Produkt Rohovce

Č. 8 / 26. FEBRUÁR 2021 / 25. ROČNÍK DUNAJSKOSTREDSKO Najčítanejšie regionálne noviny Týždenne do 33 080 domácností Najväčší výber a najprijateľnejšie ceny SBS LAMA SK od Komárna až po Bratislavu ! P.L.S. s.r.o. Ing. Peter Leporis Príďte sa presvedčiť ! webshop: agrocentrum.sk príjme strážnikov sprostredkovateľ poistenia, úverov a leasingu - člen skupiny na obchodné prevádzky v Dunajskej Strede Ponúkame poistenie: tPTÙCtNBKFULVtQPEOJLBUFűPW 850 € brutto/ mesiac tDFTUPWOÏtWP[JEJFM Nástup INHEĎ! Vyberte si najvýhodnejšie poistenie MaďarskáMMaaďaďarsskáá HurmikakiHHuurrmmikkaka i TTiTipoppoo ToptasteTToptptasa tete MaligaMaMalligaga POS nutný! Hlavná 21/1, P.O.Box 181, 929 01 Dunajská Streda Bezvírusové, bohato rodiace ovocné stromky a kríky 0948 066 491 tel./fax: 031/552 47 37, mobil: 0907 742 798, 0905 988 039, 0905 524 737 36-0003 Bratislavská 100/C, 931 01 Šamorín, mobil: 0905 491 878 INZERÁT, e-mail: [email protected] KTORÝ BJOÏ Yonkheer 07-0002 Moruša van Tets Spinefreep f Earlyy Blue PREDÁVA 1LÏLDV£V'/+Y6'Y'5$ĿBY, Široký výber sadbových zemiakov - osvedčená kvalita - spokojný pestovatelia! 0907 779 019 (;(.&,(32'V2'1&,"2GGOŀenie! 0033 - 0905 638 627 finanÎná ochrana 66 Zemiaky vo vreci Zemiaky v krabici KAMENO-PRODUKT Pripravujeme na apríl: Viniče stolové bezsemenné, ROHOVCE 158 rezistentné, klasické, Výroba a montáž viac, ako 99 odrôd Bažena Mechta Fermera Bogatyr na mieru: AGROCENTRUM Topoľníky, Hviezdna 234/87, tel.: +421 031 558 26 64 Zemiaky predávame od začiatku marca, ovocné stromky cca od 20. marca obklady krbov 07-0013 schody parapety pracovné dosky obklady a dlažby Bezkonkurenčné ceny! Bezkonkurenčné 26. rokov na trhu 26. rokov 461210027 Predajňa STRECHYNA KĽÚČ AKCIA Dunajská Streda, ul. Istvána Gyurcsóa 1197/10 ARRI s.r.o. -

O K R E S N Ý F U T B a L O V Ý Z V

1 OBLASTNÝ FUTBALOVÝ ZVÄZ 929 01 DUNAJSKÁ STREDA, Ádorská 37 telefón + záznamník + fax: 031/552-22-40 mobil: 0908/724-694 http://www.obfzds.sk e-mail: [email protected] Bankové spojenie : VÚB Dunajská Streda Číslo účtu : 1205268056/0200 Názov účtu : ObFZ DUNAJSKÁ STREDA IČO : 35591102 DIČ : 2021940657 Zasadnutia odborných komisií: štvrtok od 16.00 hod. – DK, ŠTK, KR R O Z P I S MAJSTROVSKÝCH FUTBALOVÝCH SÚŤAŽÍ RIADENÝCH ObFZ DUNAJSKÁ STREDA na súťažný ročník 2011/2012 Určené: - Futbalovým klubom (oddielom) okresu Dunajská Streda - Oblastným futbalovým zväzom v regióne Západného Slovenska - Členom Rady, Výkonného výboru a odborných komisií ObFZ - Rozhodcom a delegátom súťaží riadených ObFZ - Rozhodcom okresu v súťažiach ZsFZ Slovenský futbalový zväz adresa: 821 01 Bratislava, Trnavská cesta 100/II Internetová stránka: http://www.futbalsfz.sk Telefón: 02/4820-6000, fax: 02/4820-6099 e-mail: [email protected], [email protected] Západoslovenský futbalový zväz adresa: 949 01 Nitra, Rázusova ul. 23 Internetová stránka: http://www.zsfz.sk Matrika – telefón: 037/652-34-02, fax: 037/655-48-16 e-mail: [email protected] 2 ORGÁNY A KOMISIE OBLASTNÉHO FUTBALOVÉHO ZVÄZU: RADA: predseda: BENOVIČ Arpád členovia: AMBRUS Zoltán BORBÉLY Július CSÓKA Alexander CSOMOR Jozef GAVLÍDER Štefan LÉPES Juraj NAGY Milan NÉMETH Andrej PUHA Imrich SÁTOR Zoltán SOMOGYI Ivan TOMANOVICS Karol WIMMER Ladislav WUNDERLICH Zsolt VÝKONNÝ VÝBOR: predseda: BENOVIČ Arpád členovia: FEKETE Vojtech KÁSA Karol KOVÁCS Imrich TAKÁCS Tibor REVÍZNA KOMISIA: predseda: BOTT Ján -

Obsadenie Rozhodcov Č.4 28.8.2019

OBSADENIE ROZHODCOV Č.4 28.8.2019 SÚTAŽ VI. Liga ObFZDS KOLO. 4 31. augusta - 1. septembra 2019 POZN DOMÁCI HOSTIA ROZHODCA AR1 AR2 DELEGÁT HP so 13.30 Baloň Michal n/O Ürögi Tomáš Klempa Attila Kosár Csaba Fekete Vojtech so 16.00 Dolný Štál Ižop Szőke Ladislav Zsigray Csaba Sóki Szilárd Bazsó Štefan so 16.00 Vrakúň Okoč-Sokolec Nagy Karol Csörgő Zoltán Brunczlík Viktor Simon Štefan so 16.00 Štvrtok n/O Orechová Potôň Köver Miroslav Szalánczi Tamás Vígh Balázs Horváth Ľudovít ne 16.00 Veľká Paka Jahodná Szőke Ladislav Dohorák Tomáš Csörgő Zoltán Flaska Leonard ne 15.00 Sap-Ňárad Baka Bors Norbert Szalánczi Tamás Kosár Csaba Gaál Tomáš ne 16.00 Horný Bar Horná Potôň Klempa Attila Brunczlík Viktor Sóki Szilárd Fekete Vojtech ne 16.00 Holice FK Zlaté Klasy Ürögi Tomáš Hodosi Mikuláš Virág Zsolt Földes Richard SÚTAŽ VII. Liga - JUH KOLO. 4 31. augusta - 1. septembra 2019 POZN DOMÁCI HOSTIA ROZHODCA AR1 AR2 DELEGÁT HP so 16.00 Kráľ. Kračany Čilizská Radvaň Virág Zsolt Hodosi Mikuláš Póda Roland Flaska Leonard so 16.00 Veľké Dvorníky Kútniky Dohorák Tomáš Czucz Tibor Zirig Ádám Gaál Tomáš ne 16.00 Ohrady Trhová Hradská Köver Miroslav Szabó Dávid Póda Roland Bazsó Štefan ne 16.00 Padáň Sap-Ňárad B Vígh Balázs Kozmová Emese Medveďov voľno SÚTAŽ VII. Liga SEVER KOLO. 4 31. augusta - 1. septembra 2019 POZN DOMÁCI HOSTIA ROZHODCA AR1 AR2 DELEGÁT HP so 16.00 Orechová Potôň B Blahová Bors Norbert Koczó Jozef Szabó Dávid Földes Richard ne 10.30 Blatná n/O Trstená n/O Nagy Karol Ürögi Tomáš Klempa Attila Hancko Ladislav ne 16.00 Čakany Rohovce Nagy Karol Putyera Patrik Horváth Ľudovít ne 16.00 Trnávka Mierovo Czucz Tibor Zirig Ádám FCR Zlaté klasy voľno OBSADENIE ROZHODCOV Č.4 28.8.2019 SÚTAŽ VI. -

Dunajskostredsko 20 / 27

Č. 27 / 3. JÚL 2020 / 24. ROČNÍK DUNAJSKOSTREDSKO Najčítanejšie regionálne noviny Týždenne do 33 080 domácností Kúpať sa v krištálovo čistej vode... Kristálytiszta vízben fürdeni... Dunajská Streda tel.: 0905 901 604 Pre amatérov, Pre aj pre náročných aj pre Galantská cesta 360/12, Galantská cesta e-mail: [email protected] Bazénová chémia PREDAJ - PORADENSTVO Gazdovský rad 41 DOM SLUŽIEB, Šamorín tel.: 031/562 22 52 www.agrosam.sk 07-0076 KÖLCSÖNZÉSE STAVEBNÉHO NÁRADIA STAVEBNÉHO KAMENO-PRODUKT pon.-piat.: 7.00-17.00, sob.: 7.00-12.00 sob.: 7.00-17.00, pon.-piat.: ROHOVCE 158 Výroba a montáž www.aktaon.com na mieru: ŠIROKÝ OTVORENÉ: obklady krbov POŽIČOVŇA POŽIČOVŇA SZERSZÁMGÉPEK SORTIMENT 07-0005 schody tesárstvo - klampiarstvo - pokrývačstvo parapety pracovné dosky obklady a dlažby TOVAR, SERVIS - DODÁME DO 2 HODÍN Bezkonkurenčné ceny! Bezkonkurenčné 25. rokov na trhu 25. rokov Rezivo, OSB dosky, škridla, odkvapy, strešné okná ARRI s.r.o., Budovateľská 20, Okoč, tel.: 0905 746 124, www.strecha.ws 07-0075 STRECHYNA KĽÚČ Najlepší výber KOTLOV predaj - montáž - servis Predajňa Dunajská Streda, ul. Istvána Gyurcsóa 1197/10 škridla výpredaj Predajňa: Tomášikova 35 a 37, BA 02-49 10 30 40 / [email protected] (pri predajni DIEGO) 3,50 €/m2 94-0096 mobil: 0905 387 343 e-mail: [email protected] Cenové ponuky ZDARMA ARRI s.r.o. Inzercia tel./fax: 031/55 986 89 mobil: 0905 387 343 090509 746 124 0907 779 019 www.strecha.ws e-mail: [email protected] 07-0012 07-0082 DS20-27 strana 1 SLUŽBY Najčítanejšie regionálne noviny 2 DUNAJSKOSTREDSKO Redakcia: Trhovisko 10 DUNAJSKÁ STREDA [email protected] Vydavateľ: REGIONPRESS, s.r.o. -

Köszönet Az Aktivitásért 2

A csallóközcsütörtökiekHÍRNÖK lapja V. évfolyam 2. szám 2009. július Utassy József Holtpont 1. Jaj, most vagyok csak igazán árva, sárgaház sahja, kékség királya, most vagyok én csak igazán árva: görbe fának is egyenes lángja! Köszönet az aktivitásért 2. Választott az ország, vá- érvényesen szavazó 871 Unió - Demokrata Párt 11 Mint ama nagy, hamuhodó madár, lasztott falunk lakossága polgárunk közül 825 Iveta voksot szerzett. Hat szava- ki tolla tábortüzéből éled, is. Áprilisban az elnökvá- Radičovát támogatta, zatot kapott a Szabadság üzenem neked — a szél megtalál —, lasztás második fordulója míg Ivan Gašparovič 46 és Szolidaritás új, parla- hogy élek, barátom, újra élek: okán, június 6-án pedig az szavazatot kapott. Mint menten kívüli párt, ötöt mint ama nagy hamuhodó madár. európai parlamenti kép- tudjuk, a választást végül a választások országos viselők kiválasztása miatt Ivan Gašparovič nyerte, győztese, a Smer, négyet járultunk az urnákhoz. aki időközben már meg is a Kereszténydemokrata 3. Minthogy a választás jog kezdte második államfői Mozgalom, hármat a De- Add már ajakamnak a szót, és nem kötelesség, termé- időszakát. mokratikus Szlovákiáért idegeimre a vonót, szetesen nem minden pol- Mozgalom - Néppárt, ket- zendítsd rám a csontok csöndjét gárunk élt a lehetőséggel. Az európai parlamenti tőt Szlovákia Kommunista azt a száz csillagra valót! Annál inkább illik megkö- választások iránt kisebb Pártja, egyet-egyet pedig szönni azok aktivitását, volt az érdeklődés lako- a Demokrata Párt, a Sza- Add már ajakamnak a szót akik szavazataikkal hoz- saink körében, hiszen az bad Fórum és a Szlovákia kifütyülnek így a rigók, zájárultak a választások 1 396 jogosult polgárból Konzervatív Demokratái- dáridót csapnak, dáridót! sikerességéhez. csak 286-an vették át a Polgári Konzervatív Párt szavazócédulákat és csak koalíció. -

PHSR Obce Luc Na Ostrove 2016-2020

Program hospodárskeho a sociálneho rozvoja obce Lúč na Ostrove na roky 2016-2020 Názov: Program hospodárskeho a sociálneho rozvoja obce Lúč na Ostrove na roky 2016-2020 Územné vymedzenie : Obec Lúč na Ostrove Územný plán obce schválený: áno Dátum schválenia PHSR: 08. 01. 2016 Dátum platnosti: od 09. 01. 2016 do 31. 12. 2020 Verzia1 1.0 Publikovaný verejne: 09. 01. 2016 1 Prvé prijaté znenie sa označuje číslom 1.0. V prípade zásadnej zmeny sa ďalšie aktualizované verzie označujú 2.0, 3.0 atď. V prípade malých zmien sa označuje 1.1. Riadiaci tím spracovania Programu hospodárskeho a sociálneho rozvoja obce Lúč na Ostrove na roky 2016-2020 Zoznam členov Riadiaceho tímu Mgr. Ladislav Kiss – starosta obce Lúč na Ostrove Anikó Nagyová – zástupkyňa starostu obce Lúč na Ostrove Ing. Jozef Török – hlavný kontrolór obce Lúč na Ostrove Zoltán Balogh – poslanec obecného zastupiteľstva obce Lúč na Ostrove Tomáš Csáky – poslanec obecného zastupiteľstva obce Lúč na Ostrove 2 Program hospodárskeho a sociálneho rozvoja obce Lúč na Ostrove 2016-2020 Obsah ÚVOD ........................................................................................................................................ 4 A – ANALYTICKÁ ČASŤ ...................................................................................................... 6 Vymedzenie riešeného územia ............................................................................................................................. 6 Základné fyzickogeografické charakteristiky obce .......................................................................................... -

201611-Mesiac November 2016

REGIONÁLNY ÚRAD VEREJNÉHO ZDRAVOTNÍCTVA so sídlom v Dunajskej Strede Veľkoblahovská 1067, 92901 Dunajská Streda _______________________________________________________________________ Číslo:RH/2016/009720/BM7 Dunajská Streda 2.12.2016 Podľa rozdeľovníka Vec: Mesačný výkaz prenosných ochorení za mesiac november 2016 za okres Dunajská Streda Ochorenie Počet Miesto ochorenia Salmonelóza 16 Dunajská Streda-1, A02.0 Kráľovičové Kračany-1, Lehnice-1, Nový Život-3, Šamorín-2, Štvrtok na Ostrove-2, Veľké Blahovo-3, Zlaté Klasy-3 Iné bakteriálne črevné infekcie 32 Báč-1, Bellova Ves-1, Dolný Štál-1, A04.0, A04.5, A04.7 Dunajská Streda-6, Holice-1, Horná Potôň-1, Kráľovičove Kračany-2, Lehnice-3, Nový Život-3, Ohrady-1, Okoč-1, Orechová Potôň-2, Šamorín-2, Štvrtok na Ostrove-1, Topoľníky-1, Veľké Dvorníky-1, Veľký Meder-3, Zlaté Klasy-1. Vírusové enteritídy 11 Baka-1, Dolný Bar-1, Dunajská A08.0, A08.1, A08.2 Streda-4, Gabčíkovo-1, Hubice-1, Okoč-2, Štvrtok na Ostrove-1 Divý kašeľ vyvolaný Bordatella 1 Michal na Ostrove-1 pertussis A37.0 Šarlach (scarlatína) 1 Kráľovičove Kračany-1 A38 Septikémie 8 Dunajská Streda-3, Gabčíkovo-1, A40.8, A41.0, A41.1, A41.5 Horná Potôň-1, Jahodná-1, Ohrady-1, Vrakúň-1 Urogenitálna trichomonóza 1 Dunajská Streda-1 A59.0 Varicella 28 Dunajská Streda-2, Horná Potôň-14, B01.9 Horný Bar-1, Lehnice-1, Michal na Ostrove-1, Veľký Meder-7, Zlaté Klasy-2 Zoster bez komplikácie 1 Veľké Blahovo-1 B02.9 Akútna hepatitída A 8 Okoč-7, Zlaté Klasy-1 B15 - 2 - Gamaherpesvírusová 1 Dunajská Streda-1 mononukleóza B27.0 Cytomegalovírusová 1 Kostoľné Kračany-1 mononukleóza B27.1 Nešpecifikovaná toxoplazmóza 1 Macov-1 B58.9 Svrab-scabies 3 Vieska-1, Zlaté Klasy-2 B86 Pneumónia vyvolaná Mycoplasma 1 Jahodná-1 pneumoniae J15.7 Nozokomiálne nákazy 11 Dunajská Streda-11 A04.7, J18.0, N30, P38, P39.1, A41.1, A41.5 Kontakt alebo ohrozenie 3 Dobrohosť-1, Michal na Ostrove-1, besnotou Veľká Paka-1 Z20.3 Nosič vírusovej hepatitídy B 2 Kútniky-1, Trhová Hradská -1 Z22.5 I. -

NON-TECHNICAL SUMMARY I. PURPOSE of the PROJECT At

R7 Expressway Dunajská Lužná - Holice NON-TECHNICAL SUMMARY I. PURPOSE OF THE PROJECT At present, the traffic in the section of Dunajská Lužná - Holice is run along the existing road I/63 which no longer meets current traffic loads for its condition and technical parameters and degrades the environment and threatens the safety of residents in the surrounding villages by emissions and noise. The purpose of the planned construction is building a capacity, divided four-lane directional communication, in the optimal route in terms of traffic flow and safety. The transit traffic is excluded from the territory of neighbouring municipalities by construction and operation of expressway and thereby the impact of transport on the population and the environment is improved. II. BRIEF DESCRIPTION OF THE TECHNICAL DESIGN The section of R7 expressway begins between the village of Dunajská Lužná and the town of Šamorín, where construction is linked on the section included within DZP (Documentation for zoning permit) "R7 expressway, Bratislava - Dunajská Lužná" right after the Dunajská Lužná interchange. R7 is run along the left side of the road I/63 (to the north) in its entire length mostly on agricultural lands. From the connection to the previous section the route starts to deviate from the road I/63 to the north so as to bypass Šamorín on the north. At about 0.800 km the route crosses a regional bio-corridor Danube - Little Danube by an overpass, paving the way for its elevated junction below R7. Furthermore, the route gets into the space between the town of Šamorín and the village of Kvetoslavov (closer to Kvetoslavov).