Workers Compensation Commission

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Handy Guide for Homeless Women in Regional Queensland

THE HANDY GUIDE FOR HOMELESS WOMEN IN REGIONAL QUEENSLAND 2019-2021 v9.0 ABOUT THIS PUBLICATION © 2019 The Lady Musgrave Trust, Brisbane. The Handy Guide for Homeless Women in Title: Regional Queensland (2nd edition) provides The Handy Guide for Homeless Women in vital support for women who are without Regional Queensland (2019-2021 Edition) shelter or at risk of becoming homeless. Details First published: include: 2017. Brisbane, Australia • Emergency Phone Numbers Author/Contributors: • Accommodation such as drop-in support The Lady Musgrave Trust, Centacare, centres, accommodation units and housing Griffith University and the Queensland services Department of Housing and Public Works, • Food and welfare; such as food vans, The Working Group (represented by various kitchens and Centrelink Agencies), Yet Another Creative • Health services such as hospitals, street Edited by: doctors and community health centres Karen Lyon Reid, CEO, • Legal assistance for tenancy/housing The Lady Musgrave Trust problems, and victims of crime Graphic Design by: • Community and specialist services for Rowland. domestic violence support, family and Communication, Digital and Creative Agency immigration support 07 3229 4499 • Facilities such as public libraries, lockers, free rowland.com.au transport and toilets Content-Editing & Layout by: • Employment Stephen Scott This publication originated as a partnership Yet Another Creative between The Lady Musgrave Trust, Centacare, 0410 697 314 the Department of Housing and Public Works, yetanother.co Griffith University and the Forum Working Printed by: Group. Q Print Group 07 3262 3100 qprintgroup.com.au No. of Pages: 112 CONTACT THE LADY MUSGRAVE TRUST TO: • obtain additional copies of this publication • add or correct contacts for future editions 07 3077 6760 [email protected] ladymusgravetrust.org.au Digital Edition: 2.1 Has the Guide been Handy for you? Whether you've used the Guide to help you in tough times, or if you use the Guide in your work to help others, we'd love to know what we're doing right .. -

CAO Semiannual Report January – June 2011

CAO Semiannual Report January – June 2011 Submitted August 15, 2011 TABLE OF CONTENTS From the Chief Administrative Officer ........................................................................1 Executive Summary .........................................................................................................3 Timeline .............................................................................................................................4 About Chief Administrative Officer Dan Strodel .....................................................5 Finance New Financial System ....................................................................................................5 Payroll and Benefits ........................................................................................................6 Procurement Management ...........................................................................................7 Assets, Furnishings, and Logistics Carpet Cleaning ..............................................................................................................8 Renovation of Cannon Caucus Room .........................................................................8 Furniture Refurbishment ................................................................................................8 Graphics ............................................................................................................................8 Transition Survey .............................................................................................................9 -

Major Breakthrough for Seven with US Commission for My Kitchen Rules

Major breakthrough for Seven with US commission for My Kitchen Rules FOX Broadcasting Company signs Seven to create My Kitchen Rules for the United States television market The Seven Network – Australia’s most-watched broadcast television platform and a key business of Seven West Media, one of Australia’s leading integrated media and content creation companies - today announced its next move in its long-term strategy in the development and creation of market-leading content in international markets. Building on the increasing international recognition of Seven’s created and produced My Kitchen Rules, the company today confirmed that FOX Broadcasting Company (FOX), one of the “big four” television networks in the United States has signed Seven to create and produce My Kitchen Rules for the United States. The programme – a celebrity version of the successful format - has commenced filming. Today’s signing with FOX for the United States builds on Seven’s agreement to create and produce My Kitchen Rules for Channel 4 in the United Kingdom and joins New Zealand, Serbia, Russia, Denmark, Belgium, Canada, Norway, Germany and Lithuania with “local” versions of the Seven format. In addition, the Australian version of My Kitchen Rules is seen in more than 160 territories around the world. Commenting, the Chief Executive Officer and Managing Director of Seven West Media, Tim Worner, said: “We are very excited to be working with FOX on this one. My Kitchen Rules is truly a labour of love for all of us at Seven. It has played and continues to play such an important role across all parts of our business. -

HOMESTAY FAMILY GUIDE a Guide for Victorian Government Schools Parent-Nominated and School-Sourced Homestay Families

HOMESTAY FAMILY GUIDE A guide for Victorian government schools parent-nominated and school-sourced homestay families Melbourne, Australia Department of Education and Training HOMESTAY FAMILY GUIDE FOR PARENT-NOMINATED AND SCHOOL-SOURCED HOMESTAY FAMILIES \ 1 Published by the International Education Division Department of Education and Training Melbourne, March 2020 © State of Victoria (Department of Education and Training) 2020 The copyright in this document is owned by the State of Victoria (Department of Education and Training), or in the case of some materials, by third parties (third party materials). No part may be reproduced by any process except in accordance with the provisions of the Copyright Act 1968, the National Education Access Licence for Schools (NEALS) (see below) or with permission. An educational institution situated in Australia which is not conducted for profit, or a body responsible for administering such an institution, may copy and communicate the materials, other than third party materials, for the educational purposes of the institution. Authorised by the Department of Education and Training, 2 Treasury Place, East Melbourne, Victoria, 3002. This document is also available on the internet at www.study.vic.gov.au 2 \ HOMESTAY FAMILY GUIDE FOR PARENT-NOMINATED AND SCHOOL-SOURCED HOMESTAY FAMILIES Contents About this guide 7 Getting to know your homestay student before they arrive 8 Homestay family responsibilities 9 Suggested homestay pre-arrival checklist 10 When your homestay student arrives 11 Communication -

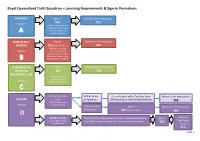

Licensing Requirements & Sign in Procedures

Royal Queensland Yacht Squadron – Licensing Requirements & Sign-In Procedures MEMBERS Sign –In Allowed Take Away Liquor Category NO YES Members must produce membership card when asked or validate ID through database GUEST\S OF A Sign-In Allowed Take Away Liquor MEMBER YES (mark as Cat ‘B’) NO Member to provide Category name and member number on sign-in slip. Guest\s to remain in the company of the member MEMBER OF AN Sign-In Allowed Take Away Liquor APPROVED NO YES RECIPROCAL CLUB Must view their Membership card Category (See Attachment 1) WHERE DO THEY Within 15 km Can only enter with a Day Pass Social Allowed Take Away Liquor VISITORS LIVE? of Squadron Membership or other RQ Membership YES Must produce valid Category Driver’s Licence Outside 15 km Sign In Allowed Take Away Liquor of Squadron YES (mark as Cat ‘D’) NO D MOTEL GUESTS The Squadron’s ‘House Rules & Policy’ states Manly Marina Sign In Allowed Take Away Must produce Motel Cove Motel guests are granted Temporary Membership YES identification Liquor YES Page 1 Royal Queensland Yacht Squadron – Licensing Requirements & Sign-In Procedures SIGN-IN SPORTING SPORTING INSURANCE PEOPLE HERE FOR THE Allowed Take VISITORS (only required for persons SPORTING EVENT BUT NOT YES Away Liquor wishing to sail) PARTICIPATING IN EVENT. (mark as Cat ‘E/F’) (WAGS | REGATTAS | (eg Parents, Guardians, YES ACADEMY, INCLUDES YA SILVER CARD partners etc) PARENTS & GUARDIANS OF CHILDREN) YES NO Category Entry Permitted Require Day E & F On presentation Pass of Silver Card or Membership or other club other -

The Longest Conflict

The Longest Conflict: Australia’s Climate Security Challenge The Longest Conflict: Australia’s Climate Security Challenge CONTENTS FOREWORD ..................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................... 7 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY .................................................................................................................................................................................................................. 9 Report overview ...................................................................................................................................................................................................................... 9 Entering the longest conflict ........................................................................................................................................................................................... 10 1. EMERGING CLIMATE CHANGE SECURITY THREATS ............................................................................................................................................... 13 The longer term climate change threats to human security ............................................................................................................................. 13 Australia’s external dilemma - Asia is a frontline for climate change crises ............................................................................................ -

Online Newsletters How Do They Work?

Editor: Norma Vaughan Vice-Chairman: Peter Flanigan [email protected] [email protected] Website: https://sites.google.com/site/u3anetworkwa Online Newsletters Inside This Issue How do they Work? Online Newsletters 1 THIS IS A PRINTED VERSION OF Notice of AGM 17 July 2014 2 THE ONLINE NEWSLETTER. A Little Light Reading 2 Congratulations! You have reached the 7th issue of the Online Learning French 3 Newsletter of U3A Network WA Inc. Items of interest will be up- Perth Seminar 3 - 4 loaded to this space over the next News from Geraldton 5 few months as they arrive on the Editor's desk. At the end of the Learners Week 6 next publication cycle, in February 2015, the content is printed off for Chess by Email 6 distribution to people who do not have access to a computer, then a U3A Armadale 7 new issue begins . Geraldton Bus Trip 8 Everyone has a story. All individual members are encouraged to sub- Meeting in Manjimup 9 mit articles of interest to the Edi- tor. These might include good news stories, visits from interesting Guest Speakers, most popular courses, successful excursions, or The articles contained in this News- ideas that have worked for your letter were displayed online on our group. Photos are most welcome. website between April 2014 and Go the smartphones!!!! October 2014. 1 OCTOBER 2014 Page 2 AGM Everyone is welcome to stay on after the Perth Seminar for the WA Network AGM. All discussion is encouraged and indeed most welcome, however when it comes to voting, only your nominated Delegate may cast a vote on your District's behalf. -

Rose Finn-Kelcey

Rose Finn-Kelcey Born in Northhamption , in 1945. Lived and worked in London from 1968 - 2014 Selected Solo Exhibitions and Installations 2020 Rose Finn-Kelcey, Kate MacGarry, London 2019 Bureau de Change, Tate Britain Truth, Dare, Double-Dare, Rose Finn-Kelcey and Donald G Rodney, 1994.Part of On Allyship, ICA Theatre, London. Event with disability activists David Ruebain and Lela Kogbara, hosted by Leah Clements 2018 Power for the People, Firstsite, Colchester 2017 Life, Belief and Beyond, Modern Art Oxford 2006 Rose Finn Kelcey, Milton Keynes Gallery, Milton Keynes 2004 Angel, St Paul’s Church, Bow, London 2003 Bureau de Change, The Irish Museum of Modern Art, Dublin 1997 Rose Finn-Kelcey, Camden Arts Centre, London 1994 Just Minus, The British School at Rome, Italy Truth Dare, Double Dare (a collaboration with Donald Rodney) The Ikon Gallery, Birmingham 1993 Rose Finn-Kelcey, Galerie l’Ollave, Lyon, France 1992 Steam Installation, Rose Finn-Kelcey, Chisenhale Gallery, London 1988 Bureau de Change, Matts Gallery, London 1984 Black and Blue – The Button Pusher’s View of Paradise, Matts Gallery, London 1978 Book and Pillow, Galleria del Cavallino, Venice, Italy (with Tina Keane) 1974 Rose Finn-Kelcey, Midland Gallery, Nottingham 1972 Power for the People, Battersea and Bankside Power Stations (installation) 1970 Here is a Gale Warning’ at Art Spectrum, Alexander Palace, London (installation) 1969 Flags, Railway embankment, Berkhamsted, Hertfordshire Selected Performances 1987 New Works Newcastle, Laing Gallery, Newcastle; Cartwright -

Today's Television

FRIDAY MAY 26 2017 TV 27 Zits Insanity Streak GIOVANNI ! WoW MANY TIMES MUST I TELL You ? GLUE THE PLATES To TI-lE TASLE ! CAPISCE! Snake Tales Swamp NO,SU"f" l-IE I-lA~ A WAL-L-E1" FUL-L OF PIC-ruRe.S OF NEAR MRS!! 260517 Start the day Today’s TeleVision with a laugh nine scTV darwin abc sbs Ten digiTal 6.00 Today. (CC) 6.00 Sunrise. (CC) 6.00 News. (CC) 9.00 ABC News. 6.00 WorldWatch. 9.30 Greek 6.00 Ent. Tonight. 6.30 GCBC. Have you heard the joke 9.00 Today Extra. (PG, CC) 9.00 The Morning (CC) 10.00 One Plus One. (CC) News. 10.30 German News. 11.00 7.00 My Market Kitchen. 7.30 about the butter? 11.30 Morning News. (CC) Show. (PG, CC) 10.30 Compass. (PG, R, CC) 11.00 Spanish News. 12.00 Arabic Bold. (PG) 8.00 Family Feud. 8.30 12.00 The Ellen DeGeneres 11.30 Seven Morning Grand Designs. (R, CC) 12.00 ABC News. 12.30 Turkish News. 1.00 Studio 10. (PG) 11.00 The Talk. I’d better not tell you, it Show. (PG, CC) News. (CC) News At Noon. (CC) 1.00 Joanna PBS News. (CC) 2.00 The Chefs’ (PGlv) 12.00 Dr Phil. (PGadl, CC) might spread. Variety show. 12.00 Wanted. (Mv, R, CC) Lumley’s Japan. (PG, R, CC) 2.00 Line. (R, CC) 2.30 The Point 1.00 The Living Room. (PG, R, CC) 1.00 MOVIE: Benny And Joon. -

Seven Productions' House Rules Goes Global

Seven Productions’ House Rules Goes Global 6 June 2017 -- Seven Productions, the production arm of Australia’s market-leading Seven Network, today confirmed that one of its key franchises, House Rules, has secured a significant international broadcast breakthrough. House Rules has been commissioned by ProSiebenSat.1 Media in Germany. It will be produced by RedSeven Entertainment, a part of Red Arrow Entertainment Group. This new commission builds on the enormous success House Rules has achieved in the Netherlands where a second season has delivered exceptional ratings for Net5. In addition to a continued focus on the development of local formats, the Australian version of House Rules is broadcast across multiple international markets, including Ireland, Spain, the Philippines, Canada, France, Russia, Portugal, South Africa, Hungary, Belgium, Latin America, Germany, New Zealand and Italy. In Australia, House Rules is up 9.2% in audience on 2016 and growing. This year, it has delivered a peak viewing audience of 2.43 million and market leadership in total viewers, 16-39s, 18-49s and 25-54s. Seven has confirmed the commissioning of a new series for the 2018 Australian television season. Commenting, Therese Hegarty, Director of Content and Rights for Seven said: “The confirmation of this local commission with ProSiebenSat.1 Media in Germany is testament to the strength of the House Rules format. We are excited with this development and look forward to House Rules continued success in global markets.” House Rules’ increasing international footprint mirrors the success of one of Seven’s other key franchises, My Kitchen Rules. Seven has created and produced My Kitchen Rules for FOX in the United States and Channel 4 in the United Kingdom, and for TVNZ in New Zealand. -

Auto Motive Breaking House Rules

VVision Magazine ISION1 Auto Motive Toyota Dealership Chatswood, Sydney Breaking House Rules Nepean Hospital Mental Health Care Unit, Penrith NSW CONTENTS Auto Motive Cool, calm and connected, SBA’s design for Toyota’s new flagship premises is all high legibility and fine detailing. 04 3 Twitter Blog Subscribe Submit VISION welcomes project submissions to our editorial team, please submit ideas and projects clicking the icon above. Breaking House Rules A precisely focused glazing program can be the difference between high and low light. Especially so, when the project is a mental health care facility – traditionally inward 23 looking and driven by security concerns. Toyota Dealership Chatswood, Sydney Contents Vision Magazine 4 DIAGONAL STEEL COLUMNS AND ELEGANT GLASS JACKET DELIVER BESPOKE ARCHITECTURE. A SOARING SINGLE VOLUME AND HIGH-END VIRIDIAN GLAZING, IMMERSE STAFF AND CUSTOMERS IN THE CRAFTED, LIGHT-FILLED SPACE. Toyota Dealership Chatswood, Sydney Principal glazing resource: Viridian ComfortPlusTM clear Seraphic DesignTM Architect: SBA Architects Pty Ltd Photography: Peter and Jennifer Hyatt Text: Peter Hyatt 5 AUTO MOTIVE Vision Magazine 6 he rise of the automobile has meant the rise of the automotive dealership and in so many Tinstances this leaves plenty to be desired. A visit to the local motor-vehicle showroom is often little better than time spent at its big siblings – the airport terminal and shopping mall – where the initial novelty soon becomes unbearable. Too often it calls for a simple strategy – get in, get out. A panacea to such dysfunction is better design and brilliant service. The average punter prefers clarity to confusion; understatement to overstatement. -

2871 Point Nepean Road, Blairgowrie VIC 3942

2871 Point Nepean Road, Blairgowrie VIC 3942 Phone: 03 5988 8088 Email: [email protected] Website: boathouseresort.com.au Reception Hours: 8.30am to 8.30pm Facebook / Instagram: @boathouseblairgowrie Welcome to the Boathouse Resort Studios and Suites We would like to warmly welcome you to the Boathouse Resort Studios and Suites and wish you a very pleasant stay with us. This compendium is designed to provide you with useful information regarding services and facilities available within our establishment, as well as in the local area. If for any reason any aspect of your stay is not satisfactory, please let our staff know immediately and we will endeavor to rectify any problems. We appreciate all feedback given and use your comments to improve accommodation and facilities. Our dedicated and friendly team are here to help make your stay memorable and enjoyable. If you require any assistance or further information, please do not hesitate to let us know. We look forward to making your stay on the Mornington Peninsula one to remember. Brett Cadan, Director CONTENTS Facilities and services Pages 2 – 5 Transportation and nearby amenities Page 6 Getting here and resort map Page 7 Resort rules Pages 8 Friends of the Boathouse Page 9 In-room publications Page 10 On-site café, restaurant & bar menus Pages 11 - 18 1 WI-FI ACCESS To access the complimentary Resort Wi-Fi, please use the following details: Login: Boathouse Guest Password: BayBeach3942 TELEPHONE To contact Reception: Dial “0” then 5988 8088 (free call). To make an external call: Dial “0” then the number required.