Ecological Survey of the Royal Canal 1989

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Flood Risk Assessment

KILDARE COUNTY COUNCIL Site-Specific Flood Risk Assessment for Proposed Development of a New Machinery Yard and Regional Salt Barn, Jigginstown, Newhall, Naas, Co Kildare Kildare County Council, Kilgallen & Partners County Hall Consulting Engineers Devoy Park Well Road, Kylekiproe Naas, Co. Kildare 17032-R-FRA Portlaoise, Co. Laois W91 X77 Issue PL1 Proposed Machinery Yard and Regional Salt Barn, Jigginstown, Newhall, Naas Site-Specific FRA REVISION HISTORY Client Kildare County Council Proposed Development of a New Machinery Yard and Regional Salt Barn, Project at Jigginstown, Newhall, Naas, Co Kildare Title Report on Site-Specific Flood Risk Assessment Date Details of Issue Issue No. Origin Checked Approved 15/02/19 Initial Issue PL1 PB MK PB Doc Ref 17032-R-FRA Issue PL1 P a g e | ii Proposed Machinery Yard and Regional Salt Barn, Jigginstown, Newhall, Naas Site-Specific FRA TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. Introduction ................................................................................................................... 1 1.1 Introduction ................................................................................................................... 1 1.2 Structure of the Report ................................................................................................... 1 2. Details of Site ................................................................................................................. 2 2.1 Site Location and Description ......................................................................................... -

HERITAGE PLAN 2016-2020 PHOTO: Eoghan Lynch BANKS of a CANAL by Seamus Heaney

HERITAGE PLAN 2016-2020 PHOTO: Eoghan Lynch BANKS OF A CANAL by Seamus Heaney Say ‘canal’ and there’s that final vowel Towing silence with it, slowing time To a walking pace, a path, a whitewashed gleam Of dwellings at the skyline. World stands still. The stunted concrete mocks the classical. Water says, ‘My place here is in dream, In quiet good standing. Like a sleeping stream, Come rain or sullen shine I’m peaceable.’ Stretched to the horizon, placid ploughland, The sky not truly bright or overcast: I know that clay, the damp and dirt of it, The coolth along the bank, the grassy zest Of verges, the path not narrow but still straight Where soul could mind itself or stray beyond. Poem Above © Copyright Reproduced by permission of Faber & Faber Ltd. Waterways Ireland would like to acknowledge and thank all the participants in the Heritage Plan Art and Photographic competition. The front cover of this Heritage Plan is comprised solely of entrants to this competition with many of the other entries used throughout the document. HERITAGEPLAN 2016-2020 HERITAGEPLAN 2016-2020 TABLE OF CONTENTS Foreword ...................................................................................................................................................4 Waterways Ireland ......................................................................................................................................6 Who are Waterways Ireland?................................................................................................................6 What -

Royal Canal Urban Greenway Public Consultation Document

Royal Canal Urban Greenway Public Consultation Document Royal Canal Urban Greenway 2 Public Consultation Document Document Control Job Title: Royal Canal Urban Greenway Job Number: p170239 Report Ref: p170239-DBFL-Rep-002 Author: Mark Kelly Reviewed by: Robert Kelly Date: May 2021 Distribution: DBFL Consulting Engineers Client Revision Issue Date Description Prepared Reviewed Approved - 18/05/2021 Draft for Client Review MK RK TJ Rev A 20/05/2021 Draft for Client Review MK RK TJ Final 24/05/2021 Public Consultation MK RK TJ DBFL Consulting Engineers Dublin Office Waterford Office Cork Office Ormond House Suite 8b The Atrium 14 South Mall Ormond Quay Maritana Gate, Canada Street Cork Dublin 7 Waterford T12 CT91 D07 W704 X91 W028 Tel 01 4004000 Tel 051 309500 Tel 021 2024538 Fax 01 4004050 Email [email protected] Email [email protected] Email [email protected] Web www.dbfl.ie Web www.dbfl.ie Web www.dbfl.ie This document has been prepared for the exclusive use of our Client and unless otherwise agreed in writing with DBFL Consulting Engineers, no other party may use, make use of, or rely on the contents of this document. The document has been compiled using the resources agreed with the Client, and in accordance with the agreed scope of work. DBFL Consulting Engineers accepts no responsibility or liability for any use that is made of this document other than for the purposes for which it was originally commissioned and prepared, including by any third party, or use by others, of opinions or data contained in this document. -

Locks and Bridges on Ireland's Inland Waterways an Abundance of Fixed

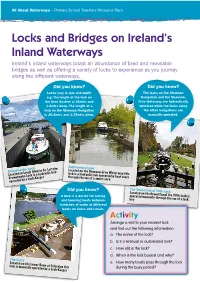

ack eachers Resource P ways – Primary School T All About Water Locks and Bridges on Ireland’s Inland Waterways Ireland’s inland waterways boast an abundance of fixed and moveable bridges as well as offering a variety of locks to experience as you journey along the different waterways. Did you know? Did you know? The locks on the Shannon Navigation and the Shannon- Locks vary in size and depth Erne Waterway are hydraulically e.g. the length of the lock on operated while the locks along the Erne System is 36mtrs and the other navigations are 1.2mtrs deep. The length of a manually operated. lock on the Shannon Navigation is 29.2mtrs and 1.35mtrs deep. Ballinamore Lock im aterway this Lock . Leitr Located on the Shannon-Erne W n in Co ck raulic lock operated by boat users gh Alle ulic lo lock is a hyd Drumshanbon Lou ydra ugh the use of a smart card cated o ock is a h thro Lo anbo L eeper rumsh ock-K D ed by a L operat The Grand Canal 30th Lock Did you know? Located on the Grand Canal the 30th Lock is operated manually through the use of a lock A lock is a device for raising key and lowering boats between stretches of water of different levels on rivers and canals. Activity Arrange a visit to your nearest lock and find out the following information: a. The name of the lock? b. Is it a manual or automated lock? c. How old is the lock? d. -

Urban Demographic Change in Ireland: Implications for the GAA

L.o. 3 S S rj Urban Demographic Change in Ireland: Implications for the GAA Club Structure Aoife Cullen Acknowledsements I wish to express my thanks to the many people who made this possible. Thank you to all the Leinster Councils Development officers who were extremely helpful and informative. A special thank you to the people who gave of their time to meet me to share their wisdom. Thanks to Kathleen O Neill who was very helpful and enthusiastic in answering any queries. A sincere thank you to Proinnsias Breathnach who offered his guidance and advice. A special thanks to my dear friend, Sonya Byrne who helped me with the finishing touches. Lastly, thanks to my family and friends who constantly encouraged and supported my efforts throughout. Table of Contents Chapter 1 - Introduction______________________________________________ 1 Chapter 2 - Literature Review__________________________________________4 Chapter 3 - Methodology_____________________________________________ 12 Chapter 4 - Research_________________________________________________ 15 A - Urban Demographic Change in Leinster And Identification of Target Towns______________________________ 15 B - Individual Towns__________________________________________ 18 ■ Carlow_________ 18 ■ Celbridge_______________________________________ 21 ■ Naas___________________________________________ 24 ■ Kilkenny_________________________________________ 21 ■ Portlaoise_______________________________________ 30 ■ Longford________________________________________ 33 ■ Drogheda________________________________________36 -

Royal Canal News January 1975 No.2

No.2. JANUARY, Royal Canal News 1975 RESTORATION - THE WAY AHEAD The past year was a momentous one for the Royal Canal and the developments that took place rose directly from the public meeting held in Maynooth at the end of 1973. There is every reason to be thankful to the organizers of that meeting for bringing together, at what has since transpired was a crucial time in the canal’s history, representatives of so many interested bodies. The events of 1974 are recorded in this and the September newsletter, but what of the future? Voluntary participation in .restoration work is increasing and will undoubtedly continue to do so, and further assistance from C.I.E. is almost certainly assured. What is needed most urgently, though, is the commitment of the Government to the eventual restoration of the whole of the canal. Restoration of the 53 miles from Dublin to Mullingar is implied in the decision of the Minister for Local Government regarding Mc Nead's Bridge, but the remaining 37 miles form the vital link to the Shannon. The first 17 miles of the latter section from Mullingar, via Ballinea, Shandonagh, Coolnahay and Ballynacargy to Abbeyshrule have, until now, remained free from obstructions to possible future navigation. It is imperative that this situation be maintained and that Westmeath County Council be persuaded to think again about their plans to culvert the canal at Shandonagh and Ballinea bridges. Unfortunately, the final 20 miles from Abbeyshrule to Cloondara have suffered at the hands of Longford County Council but the position is nowhere near as bad as would appear at first sight. -

Irish Wildlife Manuals No. 103, the Irish Bat Monitoring Programme

N A T I O N A L P A R K S A N D W I L D L I F E S ERVICE THE IRISH BAT MONITORING PROGRAMME 2015-2017 Tina Aughney, Niamh Roche and Steve Langton I R I S H W I L D L I F E M ANUAL S 103 Front cover, small photographs from top row: Coastal heath, Howth Head, Co. Dublin, Maurice Eakin; Red Squirrel Sciurus vulgaris, Eddie Dunne, NPWS Image Library; Marsh Fritillary Euphydryas aurinia, Brian Nelson; Puffin Fratercula arctica, Mike Brown, NPWS Image Library; Long Range and Upper Lake, Killarney National Park, NPWS Image Library; Limestone pavement, Bricklieve Mountains, Co. Sligo, Andy Bleasdale; Meadow Saffron Colchicum autumnale, Lorcan Scott; Barn Owl Tyto alba, Mike Brown, NPWS Image Library; A deep water fly trap anemone Phelliactis sp., Yvonne Leahy; Violet Crystalwort Riccia huebeneriana, Robert Thompson. Main photograph: Soprano Pipistrelle Pipistrellus pygmaeus, Tina Aughney. The Irish Bat Monitoring Programme 2015-2017 Tina Aughney, Niamh Roche and Steve Langton Keywords: Bats, Monitoring, Indicators, Population trends, Survey methods. Citation: Aughney, T., Roche, N. & Langton, S. (2018) The Irish Bat Monitoring Programme 2015-2017. Irish Wildlife Manuals, No. 103. National Parks and Wildlife Service, Department of Culture Heritage and the Gaeltacht, Ireland The NPWS Project Officer for this report was: Dr Ferdia Marnell; [email protected] Irish Wildlife Manuals Series Editors: David Tierney, Brian Nelson & Áine O Connor ISSN 1393 – 6670 An tSeirbhís Páirceanna Náisiúnta agus Fiadhúlra 2018 National Parks and Wildlife Service 2018 An Roinn Cultúir, Oidhreachta agus Gaeltachta, 90 Sráid an Rí Thuaidh, Margadh na Feirme, Baile Átha Cliath 7, D07N7CV Department of Culture, Heritage and the Gaeltacht, 90 North King Street, Smithfield, Dublin 7, D07 N7CV Contents Contents ................................................................................................................................................................ -

Types of Bank Accounts in Ireland

PHIBSBOROUGH ABOUT * AN AREA ON THE RISE In recent decades, Phisborough has been a growing area of the Northside of Dublin, with its characteristic red brick decks full of charm and amenities, from Dalymount Park to Mater Hospital. The last few years have seen a new focus on community life in the neighbourhood, with many students coming to live here and new unique bars, barbershops, and eco-friendly shops openings. 2 TRANSPORT It is also an area with the new Luas service (tram), the city campus of TU (Irish University of Technology), and a planned Metrolink station across the canal, only increases the attractiveness of the area. By walk Bus Bike Dublin Bikes 21 minutes to the city centre. Any of the bus routes such as 4, 9, 38A, 38B, 46A, 83, 83A, In Phisborough road you can find The Dublin bikes stop, very useful Luas 120, 122 and140 will also to move around the city! The tram will get you into get you into the city in 10-15 town in just eight minutes. minutes. Airport Aircoach Express Coach 700 3 TAKE A WALK This beautiful old area just minutes from the city centre, is rich in history. Eamon de Valera and James Joyce lived here! 4 HISTORY Phisborough started to be popular in the 19th century when the railway and canal terminal at Broadstone gave life to what was then a suburb of the city. The impressive Church of St. Peter built in 1862, and shortly after that, several of the most iconic Victorian pubs in the area followed. -

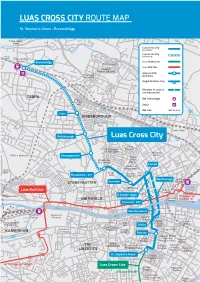

LUAS CROSS CITY ROUTE MAP Luas Cross City I

LUAS CROSS CITY ROUTE MAP Luas Cross City i St. Stephen’s Green - Broombridge GLASNEVIN Tolka Valley Park Luas Cross City (on street) Luas Cross City Royal (off street) Canal Broombridge Station Broombridge Luas Green Line Rose Garden Luas Red Line National Botanic Gardens Stops in both Glasnevin directions DRUMCONDRA Cemetery Griffith Park Single direction stop Direction of Luas on one way section Tolka Park CABRA Mount Rail Interchange Bernard Park Depot Royal Canal Rail Line Tolka River Cabra PHIBSBOROUGH Dalymount Park Croke Park Phibsborough Luas Cross City Royal Canal Mater Blessington Hospital Street Basin Mountjoy McKee Barracks Grangegorman Square Hugh Broadstone Lane Bus Garage Gallery Parnell Garden of Remembrance Dublin Zoo Kings Rotunda The Broadstone - DIT Inns Hospital Gate Marlborough Connolly STONEYBATTER Dominick Station Ilac Shopping Luas Red Line Centre Abbey Theatre O’Connell Upper GPO Phoenix Park To Docklands/ Custom The Point SMITHFIELD House O’Connell - GPO IFSC Liffey Westmoreland Heuston Guinness Liffey Station Brewery Bank of Ireland Civic Trinity Science Royal Hospital Offices City Trinity College Gallery Kilmainham Hall Dublin NCAD Christ Church Guinness Cathedral Dublin College Park KILMAINHAM Storehouse Castle Dawson Camac Leinster House River Gaiety Houses of National Theatre the Oireachtas Gallery Saint THE Patrick's Park Stephen’s Green National Natural Shopping Center Museum History Merrion LIBERTIES Museum Square Fatima St. Stephen’s Green Saint Stephen's Green To Saggart/Tallaght Luas Green Line Iveagh Fitzwilliam Gardens Square To Brides Glen National Concert Hall Wilton Park DOLPHIN’S BARN PORTOBELLO Dartmouth Square Kevins GAA Club 5-10 O3 11-13 EXTENT OF APPROVED RAILWAY ORDER REF. -

Cycle Network Plan Draft Greater Dublin Area Cycle Network Plan

Draft Greater Dublin Area Cycle Network Plan Draft Greater Dublin Area Cycle Network Plan TABLE OF CONTENTS PART 1: WRITTEN STATEMENT 3.8. Dublin South East Sector ................................................................................................ 44 INTRODUCTION 3.8.1 Dublin South East - Proposed Cycle Route Network........................................................... 44 CHAPTER 1 EXISTING CYCLE ROUTE NETWORK ....................................................... 1 3.8.2 Dublin South East - Proposals for Cycle Route Network Additions and Improvements...... 44 3.8.3 Dublin South East - Existing Quality of Service ................................................................... 45 1.1. Quality of Service Assessments ........................................................................................1 CHAPTER 4 GDA HINTERLAND CYCLE NETWORK ................................................... 46 1.2. Existing Cycling Facilities in the Dublin City Council Area..................................................1 4.1 Fingal County Cycle Route Network................................................................................ 46 1.3. Existing Cycling Facilities in South Dublin County Area.....................................................3 4.1.1 South Fingal Sector.............................................................................................................. 46 1.4. Existing Cycling Facilities in Dun Laoghaire-Rathdown Area .............................................5 4.1.2 Central Fingal Sector -

29 Cloon Lara Athlone Rd., Mullingar, Co.Westmeath

29 CLOON LARA ATHLONE RD., MULLINGAR, CO.WESTMEATH Deceptively Spacious 4 Bedroom Semi-De tached House In this Prestigeous New Development conveniently located near to Ballinea National School, Mullingar Equestrian Centre & Lough Ennell & all other Town Amenties (c.1.5 Miles) Master Bedroom Ensuite Gas Fired Central Heating throughout Price : €190,000 Reference : 3992b Address: 29 Cloon Lara, Athlone Rd., Mullingar, Co.Westmeath ACCOMMODATION: Entrance Hall 5.90 x 2.70 Laminate Flooring. Phone Point. Cov ing. Understair Storage (19` 4`` x 8` 10``) A rea Sitting Room 3.90 x 7.00 Laminate Flooring. TV Point. Open Hearth Marble Fireplace. (12` 9`` x 22` 11``) C oving.Bay Window. Double D oors to Kitchen Diner. Kitchen/Diner 3.80 x 3.50 Fully Fitted Built-In Kitchen Units.Tiled Floor at Kitchen A rea. (12` 6`` x 11` 6``) TV Point, E xtractor Fan. Double Glazed uPV C Patio Door to rear Garden. Dining Area Section 4.50 x 2.60 (14` 9`` x 8` 6``) Utility Room 1.80 x 1.70 Fully Fitted Units & Counter Top. Tiled Floor. Door to side of (5` 11`` x 5` 7``) House Downstairs Toilet 1.80 x 1.40 With WC., & WHB. Tiled Floors. Radiator. (5` 11`` x 4` 7``) Bedroom 1 3.08 x 2.80 Front A spect. C arpet Floors.Built-In Wardrobe (10` 1`` x 9` 2``) Bedroom 2 MASTER 3.02 x 5.50 Front A spect.C arpet Flooring. TV Point. Built-In Wardrobes. (9` 11`` x 18` 0``) Ensuite 1.83 x 1.86 With Electric Shower, WC., & WHB. -

Financial Statements for the Year Ended 30Th November

COMHAIRLE LAIGHEAN, CUMANN LUTHCLEAS GAEL FINANCIAL STATEMENTS FOR THE YEAR ENDED TH 30 NOVEMBER 2004. SEAN Ó BROIN (CISTEOIR CHOMHAIRLE LAIGHEAN C.L.G.) COMHAIRLE LAIGHEAN The Chairman and Members of 21 February 2005 Comhairle Laighean Cumann Luthchleas Gael Per Michéal Ó Dubhshláine Runaí A Chairde, We have examined the books of an Chomhairle for the year ended 30th November 2004. We enclose Revenue Account showing the working of the year and Balance Sheet showing the financial position of an Chomhairle at the end of the year. REVENUE ACCOUNT Income of the year amounted to €5,942,022. Expenditure came to €4,718,286 leaving a surplus for the year of €1,223,736. After adding the General Fund Balance at the beginning of the year, and after providing Grants for Grounds €804,159 and Loan Scheme Development Grants €925,000 there remained a balance of €3,977,366 in the General Fund. As compared with the preceding year when there was a surplus €1,335,966 the principal fluctuations were as follows:- Increase Decrease € € Income Gate Receipts 129,162 Media Coverage 22,350 Interest 35,773 Other income 44,084 Expenditure Provincial Teams Expenses 23,638 Match expenses 79,751 Conference and Travel 31,547 Administration and General 62,984 BALANCE SHEET Current Assets of an Chomhairle at 30 November 2004 amounted to €4,207,917. Current Liabilities came to €634,272 leaving Net Current Assets of €3,573,644. After adding Fixed Assets €1,060,547 and Grounds Development Loans €702,880 and after deducting Grounds Development Scheme Bank Loan €886,529, Capital