The Copp Family Textiles

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Natural Materials for the Textile Industry Alain Stout

English by Alain Stout For the Textile Industry Natural Materials for the Textile Industry Alain Stout Compiled and created by: Alain Stout in 2015 Official E-Book: 10-3-3016 Website: www.TakodaBrand.com Social Media: @TakodaBrand Location: Rotterdam, Holland Sources: www.wikipedia.com www.sensiseeds.nl Translated by: Microsoft Translator via http://www.bing.com/translator Natural Materials for the Textile Industry Alain Stout Table of Contents For Word .............................................................................................................................. 5 Textile in General ................................................................................................................. 7 Manufacture ....................................................................................................................... 8 History ................................................................................................................................ 9 Raw materials .................................................................................................................... 9 Techniques ......................................................................................................................... 9 Applications ...................................................................................................................... 10 Textile trade in Netherlands and Belgium .................................................................... 11 Textile industry ................................................................................................................... -

', :':':;"Texa's- Agricultural , Ex-Ten '

4> ~ -,' , :':':;"TEXA'S- AGRICULTURAL , EX-TEN ' . ... -:>-.~ -~•• ,....,~ hi.t~.' ~ ___ '>::"'" - 'J. E .. 'Hutchison, 'Director, College:.shlt~QP" Texas GRAHAM HARD NENA ROBERSON RHEBA MERLE BOYLES FANNIE BROWN EATON EXTENSION CLOTHING SPECIALISTS The A. and M. College of Texas THE CHARACTERISTICS OF FABRICS which . give 3. Fabrics made of chemically treated cotton, them the virtues of quick drying, crease re linen and rayon. The resin finishes are the most sistance, little or no ironing, keeping their orig commonly used. These finishes should last the inal shape and size during use and care, retaining normal life of a garment. a look of newness and fresh crispness after being worn and cleaned continuously also create sewing FABRIC SELECTION difficulties. The surface often is smoother and The best guides in the selection of quality harder which makes the fabric less pliable and fabrics are informative labels of reputable manu more difficult to handle. These qualities can facturers. Good quality finishes add to the cost cause seams to pucker. Even in the softest blends of fabrics, but compensate for the extra cost in there is a springiness which requires more care in durability and appearance. handling ease, as in the sleeve cap. Each fabric presents different problems. Look Wash-and-wear fabrics may be divided into at the fabric and feel it. Is it closely or loosely three groups: woven? Is it soft and firm, or stiff and wiry? 1. Fabrics woven or knitted from yarns of Will it fray? What style pattern do you have in 100 percent man-made fibers. These fabrics, if mind? properly finished, are highly crease resistant and The correctness of fabric grain is important keep their original shape and size during use and in sewing. -

What Were Cottons for in the Early Industrial Revolution?1

What were Cottons GEHN Conference – University of Padua, 17-19 November 2005 John Styles University of Hertfordshire [email protected] What were Cottons for in the Early Industrial Revolution?1 Fashion’s Favourite, the title of Beverley Lemire’s 1991 book on the cotton trade and consumer revolution in England, reminded us that in the eighteenth century cotton was a fashionable fabric.2 During the second half of the century, decorated cottons like sprigged muslins, printed calicoes and white tufted counterpanes established a remarkable currency as desirable fabrics for dress and furnishing at all levels in the market. They became an indispensable element of fashion. Of course we can debate exactly what ‘fashion’ means in this context. Is it fashion in the economist’s sense of regular changes in visual appearance of any type of good intended to stimulate sales? Is it fashion in the dress historian’s sense of annual or seasonal manipulation of normative appearance through clothing? Or is it fashion in the fashion pundit’s sense of those forms of self- conscious, avant-garde innovation in dress pursued by an exclusive social or cultural élite – the fashion of royal courts, the eighteenth-century ton, and later haute couture? It is a remarkable feature of cotton’s success in the later eighteenth century that it embraced fashion in each of these three senses. In the process, cotton challenged the previous supremacy of silks and woollens as fashionable fabrics. At the start of the eighteenth century the complaints of the silk and woollen producers had secured a prohibition on the import and sale of most types of cotton, then largely sourced in south Asia. -

The Rhetoric of the Saints in Middle English Bibiical Drama by Chester N. Scoville a Thesis Submitted in Conformity with The

The Rhetoric of the Saints in Middle English BibIical Drama by Chester N. Scoville A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Graduate Department of English University of Toronto O Copyright by Chester N. Scoville (2000) National Library Bibiiotheque nationale l*l ,,na& du Canada Acquisitions and Acquisitions et Bibliographie Services services bibliographiques 395 Wellington Street 395, rwW~gtm OttawaON KlAûîU4 OtÈewaûN K1AW canada canada The author has granted a non- L'auteur a accordé une licence non exclusive licence allowing the exclusive permettant à la National Library of Canada to Bibliothèque nationale du Canada de reproduce, loan, distribute or sel1 reproduire, prêter, distribuer ou copies of this thesis in microform, vendre des copies de cette thèse sous paper or electronic formats. la forme de microfiche/nlm, de reproduction sur papier ou sur format électronique. The author retains ownership of the L'auteur conserve la propriété du copyright in this thesis. Neither the droit d'auteur qui protège cette thèse. thesis nor substantial extracts fiom it Ni la thèse ni des extraits substantiels may be printed or otheMrise de celle-ci ne doivent être imprimés reproduced without the author's ou autrement reproduits sans son permission. autorisation. Abstract of Thesis for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy 2000 Department of English, University of Toronto The Rhetoric of the Saints in Middle English Biblical Dnma by Chester N. Scovilie Much past criticism of character in Middle English drarna has fallen into one of two rougtily defined positions: either that early drama was to be valued as an example of burgeoning realism as dernonstrated by its villains and rascals, or that it was didactic and stylized, meant primarily to teach doctrine to the faithfùl. -

Tartan As a Popular Commodity, C.1770-1830. Scottish Historical Review, 95(2), Pp

Tuckett, S. (2016) Reassessing the romance: tartan as a popular commodity, c.1770-1830. Scottish Historical Review, 95(2), pp. 182-202. (doi:10.3366/shr.2016.0295) This is the author’s final accepted version. There may be differences between this version and the published version. You are advised to consult the publisher’s version if you wish to cite from it. http://eprints.gla.ac.uk/112412/ Deposited on: 22 September 2016 Enlighten – Research publications by members of the University of Glasgow http://eprints.gla.ac.uk SALLY TUCKETT Reassessing the Romance: Tartan as a Popular Commodity, c.1770-1830 ABSTRACT Through examining the surviving records of tartan manufacturers, William Wilson & Son of Bannockburn, this article looks at the production and use of tartan in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. While it does not deny the importance of the various meanings and interpretations attached to tartan since the mid-eighteenth century, this article contends that more practical reasons for tartan’s popularity—primarily its functional and aesthetic qualities—merit greater attention. Along with evidence from contemporary newspapers and fashion manuals, this article focuses on evidence from the production and popular consumption of tartan at the turn of the nineteenth century, including its incorporation into fashionable dress and its use beyond the social elite. This article seeks to demonstrate the contemporary understanding of tartan as an attractive and useful commodity. Since the mid-eighteenth century tartan has been subjected to many varied and often confusing interpretations: it has been used as a symbol of loyalty and rebellion, as representing a fading Highland culture and heritage, as a visual reminder of the might of the British Empire, as a marker of social status, and even as a means of highlighting racial difference. -

Finish That Seam Barbara Short Iowa State College

Volume 30 Article 7 Number 5 The Iowa Homemaker vol.30, no.5 1950 Finish That Seam Barbara Short Iowa State College Follow this and additional works at: http://lib.dr.iastate.edu/homemaker Part of the Home Economics Commons Recommended Citation Short, Barbara (1950) "Finish That Seam," The Iowa Homemaker: Vol. 30 : No. 5 , Article 7. Available at: http://lib.dr.iastate.edu/homemaker/vol30/iss5/7 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Publications at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in The oI wa Homemaker by an authorized editor of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Finish That Seam - But fi rst be sure the finish is the proper one for you r material. Here are the recent 1 findings of two textiles and I clothing graduate students. I I j I I J I I J by Barbara Short I J Technical Journalism Junior I I I J I I I > HEN your mother was a little girl, often seam I > j W stresses stayed in the house for a week to outfit "'--- I the family each year. Then the inside of a dress was just as finished as the outside. Those seamstresses took 1. Double-stitch finish; 2. Pinked finish; 3. Q,·er-cast edges. pains to finish each seam so that they could be sure it wouldn't ravel. Recent graduate research at Iowa State has taken guesswork out of seam finishing. Find Hiltbold points out that the ridge produced when ings will mean no more unnecessary sewing or hope the edge is turned shows on certain fabrics. -

Cremation Grave Textiles Examples from Vendel Upper Class in the Vendel and Viking Periods

Journal of Nordic Archaeological Science 13, pp. 59–74 (2002) Cremation grave textiles Examples from Vendel upper class in the Vendel and Viking Periods Anita Malmius Few are aware of the fact that organic material such as textiles and leather can survive in cremation graves. Even fewer are aware that charred textile fragments contain almost the same information as unburnt prehistoric textiles. This fact provides the opportunity for comparing textiles from different groups in society, for studying textile development, and for gaining access to a much greater textile material based on the numerous crema- tion graves. In this article the outfits of the men buried in the cremation graves in “Vendla’s Mound”, dated to the Vendel and Viking Periods, are compared with those buried in the contemporaneous boat-graves in Vendel. Introduction strong materialistic attitudes to death and life thereafter. The In an overview of Scandinavian textile- and leatherworking, buried person has been provided with a full set of equipment Eva Andersson (1995: 16) observes that the textile craft for the after-life. Thanks to the custom of equipping the tends to be mentioned only in passing in the archaeological dead with rich grave-goods, we can today obtain insights literature and research discussions, and that dress is primar- into some aspects of the culture of buried persons. But only ily seen as a complement to buckles and other ornaments. certain categories of objects have been laid down in the The reason for this would seem to be ‘the shortage of finds graves – already their contempories made choices as to what and other evidence’, but also, ‘poor knowledge of what has was at the time considered suitable and representative. -

Spring Twenty Two Women's Headwear

SPRING 2022 SPRING TWENTY TWO WOMEN’S HEADWEAR & APPAREL DONE PROPER NH SPRING 2022 WOMEN THIS SEASON WE CELEBRATE THE NEW EXPLORERS. THE COLLECTION IS INSPIRED BY VINTAGE MILITARY AND WORKWEAR SILHOUETTES, BLENDED WITH SPRING THE JOYFUL RETRO AESTHETIC OF THE 1970’S. WOMEN 2022 WITH A PALETTE OF CLASSIC SEASONAL COLORS AND PRINTS, WE SET OUT TO DESIGN A RANGE THAT BALANCES STYLE THAT IS AT HOME ON CITY STREETS, OR THE ROADS LESS TRAVELED. SPRING 2022 2 SPRING 2022 3 RANCHER COLLECTION JO RANCHER RANCHER COLLECTION SPRING 2022 4 SPRING 2022 5 JO STRAW RANCHER RANCHER COLLECTION A NEW ICON | ELEGANT SILHOUETTE | PREMIUM DETAILS SPRING 2022 6 SPRING 2022 7 RENO FEDORA RANCHER COLLECTION REFINED AND RESPONSIBLY SOURCED | PREMIUM DETAILS AND FINISHES SPRING 2022 8 SPRING 2022 9 JO RANCHER RANCHER COLLECTION THE RANCHER REBORN | CRUELTY-FREE WOOL CONSTRUCTION SPRING 2022 10 SPRING 2022 11 JO RANCHER (10cm/4” Brim) XS-S-M-L (6_-7-7_-7_) • 100% wool felt • Metal headwear plaque • Adjustable Velcro strap under sweatband • Grosgrain outside band and brim taping DOVE WASHED NAVY/NAVY *BLACK 11035-DOVE 11035-WSNVY 11035-BLACK RANCHER COLLECTION BRASS 11035-BRASS PRODUCT PAGE JOANNA FELT HAT (10cm/4” Brim) XS-S-M-L (6_-7-7_-7_) • 100% wool felt • Grosgrain band • Metal headwear plaque • Adjustable Velcro strap under sweatband *BLACK PHOENIX ORANGE MOJAVE 10783-BLACK 10783-PHEOR 10783-MOJAV SPRING 2022 12 SPRING 2022 13 JOANNA PACKABLE HAT DUKE COWBOY HAT (7.5cm/3.5” Brim) (7.5cm/3” Brim) XS-S-M-L (6_-7-7_-7_) XS-S-M-L-XL (6¾-7-7¼-7½-7¾) • 100% wool felt • 100% wool felt • Grosgrain band • 5mm Grosgrain band • Metal headwear plaque • Metal headwear plaque • Adjustable Velcro strap under • D2 sweatband *BLACK MERMAID CASA BLANCA BLUE *BLACK COFFEE 10628-BLACK 10628-MERMD 10628-CABLB 10998-BLACK 10998-COFFE RENO FEDORA COHEN COWBOY (9cm/3. -

Textile Printing

TECHNICAL BULLETIN 6399 Weston Parkway, Cary, North Carolina, 27513 • Telephone (919) 678-2220 ISP 1004 TEXTILE PRINTING This report is sponsored by the Importer Support Program and written to address the technical needs of product sourcers. © 2003 Cotton Incorporated. All rights reserved; America’s Cotton Producers and Importers. INTRODUCTION The desire of adding color and design to textile materials is almost as old as mankind. Early civilizations used color and design to distinguish themselves and to set themselves apart from others. Textile printing is the most important and versatile of the techniques used to add design, color, and specialty to textile fabrics. It can be thought of as the coloring technique that combines art, engineering, and dyeing technology to produce textile product images that had previously only existed in the imagination of the textile designer. Textile printing can realistically be considered localized dyeing. In ancient times, man sought these designs and images mainly for clothing or apparel, but in today’s marketplace, textile printing is important for upholstery, domestics (sheets, towels, draperies), floor coverings, and numerous other uses. The exact origin of textile printing is difficult to determine. However, a number of early civilizations developed various techniques for imparting color and design to textile garments. Batik is a modern art form for developing unique dyed patterns on textile fabrics very similar to textile printing. Batik is characterized by unique patterns and color combinations as well as the appearance of fracture lines due to the cracking of the wax during the dyeing process. Batik is derived from the Japanese term, “Ambatik,” which means “dabbing,” “writing,” or “drawing.” In Egypt, records from 23-79 AD describe a hot wax technique similar to batik. -

Buckram Is a Heavy-Duty Bookbinding Cloth That Offers a Distinct, Woven Texture

B UCKRAM BOODLE BOOKS Buckram is a heavy-duty bookbinding cloth that offers a distinct, woven texture. PRICING Our two lines, Conservation and English, are formulated with a matte finish in Prices are per book, nonpadded with square corners. Includes Summit Leatherette or Arrestox B lining. a variety of well-saturated colors. Both are stain resistant and washable. Your See options below. logo can be foil or blind debossed or silk screened. PART No. SHEET SIZE 25 50 100 SINGLE PANEL 1 view Conservation Buckram 7001C-BUC 8.5 x 5.5 10.95 9.80 8.60 Strong, thick poly-cotton with subtle linen look 7001D-BUC 11 x 4.25 10.45 9.30 8.10 logo 7001E-BUC 11 x 8.5 13.25 12.10 10.90 7001F-BUC 14 x 4.25 11.55 10.40 9.20 red maroon green army green CBU-RED CBU-MAR CBU-GRN CBU-AGR 7001G-BUC 14 x 8.5 14.40 13.25 12.10 front back 7001H-BUC 11 x 5.5 11.65 10.50 9.30 7001I-BUC 14 x 5.5 12.75 11.60 10.40 7001J-BUC 17 x 11 19.65 18.50 17.30 SINGLE PANEL - DOUBLE-SIDED 2 views royal navy rust medium grey 7001C/2-BUC 8.5 x 5.5 10.95 9.80 8.60 CBU-ROY CBU-NAV CBU-RUS CBU-MGY 7001D/2-BUC 11 x 4.25 10.45 9.30 8.10 7001E/2-BUC 11 x 8.5 13.25 12.10 10.90 7001F/2-BUC 14 x 4.25 11.55 10.40 9.20 front back 7001G/2-BUC 14 x 8.5 14.40 13.25 12.10 7001H/2-BUC 11 x 5.5 11.65 10.50 9.30 tan brown black 7001I/2-BUC 14 x 5.5 12.75 11.60 10.40 CBU-TAN CBU-BRO CBU-BLK 7001J/2-BUC 17 x 11 19.65 18.50 17.30 DOUBLE PANEL 2 views Royal Conservation Buckram 7002C-BUC 8.5 x 5.5 18.50 17.20 15.80 CBU-ROY 7002D-BUC 11 x 4.25 19.15 17.80 16.45 7002E-BUC 11 x 8.5 23.30 21.80 20.40 7002F-BUC -

Suspension Bridge Corner, Seventh and Main Streets 3 I-- ' O LL G OREGON CITY, OREGON

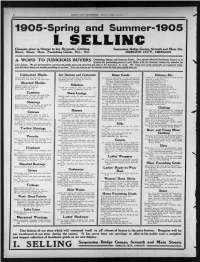

OREGON CITY ENTERPRISE, FRIDAY, APRIL 14, l!0o. (LflDTmOTTD On , Cheapest place in Oregon to buy Dry-goods- Clothing, Suspension Bridge Corner, Seventh and Main Sts. Boots, Shoes, Hats, Furnishing Goods, Etc., Etc. OREGON CITY, OREGON A. "WORD JUDICIOUS ' BUYERS Conccyning Spring and Summer Goods. Out special effort for the Spring Season is to TO increase the purchasing power of yof Dollar with the Greatest values ever afforded for your money." We are determined to convince the public more and more that out store is the best place to trade. We want yoar trade constantly and regularly when- ever the future finds you needing anything in out tine. Yog can always get the lowest prices for first class goods from ts Unbleached Muslin Art Denims and Cretonnes Dress Goods Notions, Etc. 36 inch wide, best LL, per yard, 5c. Art denims, 36 inch wide, per yard, 15e. Our line of dress goods for the Spring and Clark's O. N. T. spool cotton, 6 spools for 25o 36 inch wide, best Cabot W, per yard, 6y2c. Cretonnes, figured, oil finish, per yard, 8c. Summer of 1905 is a wonderful collection San silk, 2 spools for 5c. ' Twilled heavy, per yard, 10c. of elegant designs and fabrics of the newest Bone crochet hooks, 2 for 5c. Bleached Muslins and most popular fashions for the coming Knitting needles, set, 5c. season. Prices are uniformly low. Besf Eagle pins, 5c paper. Common quality, per yard, 5c. Silkoline 34 inch wide cashmere per yard 15c. Embroidery silk, 3 skeins for 10c. Medium grade, per yard, 7c. -

Women's Clothing in the 18Th Century

National Park Service Park News U.S. Department of the Interior Pickled Fish and Salted Provisions A Peek Inside Mrs. Derby’s Clothes Press: Women’s Clothing in the 18th Century In the parlor of the Derby House is a por- trait of Elizabeth Crowninshield Derby, wearing her finest apparel. But what exactly is she wearing? And what else would she wear? This edition of Pickled Fish focuses on women’s clothing in the years between 1760 and 1780, when the Derby Family were living in the “little brick house” on Derby Street. Like today, women in the 18th century dressed up or down depending on their social status or the work they were doing. Like today, women dressed up or down depending on the situation, and also like today, the shape of most garments was common to upper and lower classes, but differentiated by expense of fabric, quality of workmanship, and how well the garment fit. Number of garments was also determined by a woman’s class and income level; and as we shall see, recent scholarship has caused us to revise the number of garments owned by women of the upper classes in Essex County. Unfortunately, the portrait and two items of clothing are all that remain of Elizabeth’s wardrobe. Few family receipts have survived, and even the de- tailed inventory of Elias Hasket Derby’s estate in 1799 does not include any cloth- ing, male or female. However, because Pastel portrait of Elizabeth Crowninshield Derby, c. 1780, by Benjamin Blythe. She seems to be many other articles (continued on page 8) wearing a loose robe over her gown in imitation of fashionable portraits.