Rheological and Petrological Implications for a Stagnant Lid Regime on Venus

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Copyrighted Material

Index Abulfeda crater chain (Moon), 97 Aphrodite Terra (Venus), 142, 143, 144, 145, 146 Acheron Fossae (Mars), 165 Apohele asteroids, 353–354 Achilles asteroids, 351 Apollinaris Patera (Mars), 168 achondrite meteorites, 360 Apollo asteroids, 346, 353, 354, 361, 371 Acidalia Planitia (Mars), 164 Apollo program, 86, 96, 97, 101, 102, 108–109, 110, 361 Adams, John Couch, 298 Apollo 8, 96 Adonis, 371 Apollo 11, 94, 110 Adrastea, 238, 241 Apollo 12, 96, 110 Aegaeon, 263 Apollo 14, 93, 110 Africa, 63, 73, 143 Apollo 15, 100, 103, 104, 110 Akatsuki spacecraft (see Venus Climate Orbiter) Apollo 16, 59, 96, 102, 103, 110 Akna Montes (Venus), 142 Apollo 17, 95, 99, 100, 102, 103, 110 Alabama, 62 Apollodorus crater (Mercury), 127 Alba Patera (Mars), 167 Apollo Lunar Surface Experiments Package (ALSEP), 110 Aldrin, Edwin (Buzz), 94 Apophis, 354, 355 Alexandria, 69 Appalachian mountains (Earth), 74, 270 Alfvén, Hannes, 35 Aqua, 56 Alfvén waves, 35–36, 43, 49 Arabia Terra (Mars), 177, 191, 200 Algeria, 358 arachnoids (see Venus) ALH 84001, 201, 204–205 Archimedes crater (Moon), 93, 106 Allan Hills, 109, 201 Arctic, 62, 67, 84, 186, 229 Allende meteorite, 359, 360 Arden Corona (Miranda), 291 Allen Telescope Array, 409 Arecibo Observatory, 114, 144, 341, 379, 380, 408, 409 Alpha Regio (Venus), 144, 148, 149 Ares Vallis (Mars), 179, 180, 199 Alphonsus crater (Moon), 99, 102 Argentina, 408 Alps (Moon), 93 Argyre Basin (Mars), 161, 162, 163, 166, 186 Amalthea, 236–237, 238, 239, 241 Ariadaeus Rille (Moon), 100, 102 Amazonis Planitia (Mars), 161 COPYRIGHTED -

N93"14373 : ,' Atmospheric Density, Collapse of Near-Rim Ejecta Into a Flow Crudely MAGELLAN PROJECT PROGRESS REPORT

106 lnternational Colloquium on Venus ment as observed on Venus [5,6]. Such a process accounts for the results in late-stage reworking, if not self-destruction, of ejecta long run-out flows consistently originating downrange in oblique faciescmplaced earlier.Surfaceexpressionshould includebedforrns impacts (i.e., oplmsite the missing ejecta sector) even if uphill from (e.g., meter-scale dunes and decicentlmeter-scale ripples) reflect- the crater rim. Atmospheric mflxflence and recovery winds deeoupled hag eddies created in the boundary layer at the surface. Because from the gradient-controlled basal run-out flow continues down- radar imaging indicates small-scale surface roughness (as well as range and produces wind streaks in the Ice of topographic highs. resolved surface features), regions affected by such long-lived low- Turbulence accompanying the basal density flows may also produce energy processes can extend to enormous distances. Such areas are wind streak patterns. Uprange the atmosphere is drawn in behind the not directly related to ejecta emplacement but reflect the almo- f'_reball(and enhancedby the impinging impactor wake), resulting spheric equivalent to distant seismic waves in the target. Late-stage in strong winds that will last at least as long as the time for crater atmospheric processes also include interactions with upper-level formation (i.e., minutes). Such winds can entrain and saltate surface winds. Deflection of the winds around the advancing/expanding materials as observed in laboratory experiments [2,3] and inferred fireball creates a parabolic-shaped interface aloft. This is preserved from large transverse dunes uprange on Venus [2]. in the fall-out of f'mer debris for impacts directed into the winds aloft Atmospheric Effects on Ballistic EJecta: Even on Venus, (from the west) but self-destructs if the impact is directed with the target debris will be ballistically ejected and form a conical ejecta wind. -

Ooooooooo ° °

LPI Contribution No. 789 57 highest basal elevation, Maat Mons, should have a well-developed, large, and relatively deeper NBZ and that the volcano at the lowest 6055 .It .... _ .... _ .... t .... t .... I .... altitude, an unnamed volcano located southwest of Beta Regio at 10 °, 273 °, should have either a poorly developed magma chamber 6054 _ o _ o or none at all [2]. Preliminary mapping of Mast Mons [3] identified o at least six flow units that exhibit greater variations in morphology ._ o o o and radar properties than the flow• of Saps• Mons. These units are 6053 o 8 o also spatially and temporally distinct and suggest the eruption of a continuously evolving magma. Although smaller in diameter, the o oo o summit c.alders is much bener defined than the depression at Saps•. The inferred young age of Mast (lOose et at. [4] suggest that it may ooooooooo° ° ° I even be "active") may mean that the chamber has not yet grown to 605tj#o_o o 6050_ .... t", ', _ .... _ ", • i • i ' "full size." explaining the relatively smaller caldera. There is no 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 evidence of radial fractures at Maat Mons, suggesting that if lateral Height (kin) dike propagation occurxed, it was sufficiently deep that there was no surface expression. In contrast, the unnamed volcano has no summit features, no radial dikes, and only three flow units that exhibit Fig. 3. Graph showing the heights of ! l0 large volcanos as • function of considerable morphologic variations within units [3]. These obser- basal altitude. -

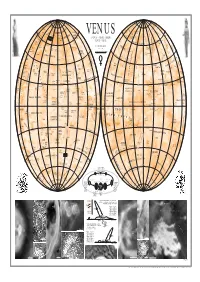

VENUS Corona M N R S a Ak O Ons D M L YN a G Okosha IB E .RITA N Axw E a I O

N N 80° 80° 80° 80° L Dennitsa D. S Yu O Bachue N Szé K my U Corona EG V-1 lan L n- H V-1 Anahit UR IA ya D E U I OCHK LANIT o N dy ME Corona A P rsa O r TI Pomona VA D S R T or EG Corona E s enpet IO Feronia TH L a R s A u DE on U .TÜN M Corona .IV Fr S Earhart k L allo K e R a s 60° V-6 M A y R 60° 60° E e Th 60° N es ja V G Corona u Mon O E Otau nt R Allat -3 IO l m k i p .MARGIT M o E Dors -3 Vacuna Melia o e t a M .WANDA M T a V a D o V-6 OS Corona na I S H TA R VENUS Corona M n r s a Ak o ons D M L YN A g okosha IB E .RITA n axw e A I o U RE t M l RA R T Fakahotu r Mons e l D GI SSE I s V S L D a O s E A M T E K A N Corona o SHM CLEOPATRA TUN U WENUS N I V R P o i N L I FO A A ght r P n A MOIRA e LA L in s C g M N N t K a a TESSERA s U . P or le P Hemera Dorsa IT t M 11 km e am A VÉNUSZ w VENERA w VENUE on Iris DorsaBARSOVA E I a E a A s RM A a a OLO A R KOIDULA n V-7 s ri V VA SSE e -4 d E t V-2 Hiei Chu R Demeter Beiwe n Skadi Mons e D V-5 S T R o a o r LI s I o R M r Patera A I u u s s V Corona p Dan o a s Corona F e A o A s e N A i P T s t G yr A A i U alk 1 : 45 000 000 K L r V E A L D DEKEN t Baba-Jaga D T N T A a PIONEER or E Aspasia A o M e s S a (1 MM= 45 KM) S r U R a ER s o CLOTHO a A N u s Corona a n 40° p Neago VENUS s s 40° s 40° o TESSERA r 40° e I F et s o COCHRAN ZVEREVA Fluctus NORTH 0 500 1000 1500 2000 2500 KM A Izumi T Sekhm n I D . -

Vénus Les Transits De Vénus L’Exploration De Vénus Par Les Sondes Iconographie, Photos Et Additifs

VVÉÉNUSNUS Introduction - Généralités Les caractéristiques de Vénus Les transits de Vénus L’exploration de Vénus par les sondes Iconographie, photos et additifs GAP 47 • Olivier Sabbagh • Février 2015 Vénus I Introduction – Généralités Vénus est la deuxième des huit planètes du Système solaire en partant du Soleil, et la sixième par masse ou par taille décroissantes. La planète Vénus a été baptisée du nom de la déesse Vénus de la mythologie romaine. Symbolisme La planète Vénus doit son nom à la déesse de l'amour et de la beauté dans la mythologie romaine, Vénus, qui a pour équivalent Aphrodite dans la mythologie grecque. Cythère étant une épiclèse homérique d'Aphrodite, l'adjectif « cythérien » ou « cythéréen » est parfois utilisé en astronomie (notamment dans astéroïde cythérocroiseur) ou en science-fiction (les Cythériens, une race de Star Trek). Par extension, on parle d'un Vénus à propos d'une très belle femme; de manière générale, il existe en français un lexique très développé mêlant Vénus au thème de l'amour ou du plaisir charnel. L'adjectif « vénusien » a remplacé « vénérien » qui a une connotation moderne péjorative, d'origine médicale. Les cultures chinoise, coréenne, japonaise et vietnamienne désignent Vénus sous le nom d'« étoile d'or », et utilisent les mêmes caractères (jīnxīng en hanyu, pinyin en hiragana, kinsei en romaji, geumseong en hangeul), selon la « théorie » des cinq éléments. Vénus était connue des civilisations mésoaméricaines; elle occupait une place importante dans leur conception du cosmos et du temps. Les Nahuas l'assimilaient au dieu Quetzalcoatl, et, plus précisément, à Tlahuizcalpantecuhtli (« étoile du matin »), dans sa phase ascendante et à Xolotl (« étoile du soir »), dans sa phase descendante. -

Refining the Mahuea Tholus (V-49) Quadrangle, Venus

3rd Planetary Data Workshop 2017 (LPI Contrib. No. 1986) 7118.pdf REFINING THE MAHUEA THOLUS (V-49) QUADRANGLE, VENUS. N.P. Lang1 , K. Rogers1, M. Covley1, C. Nypaver1, E. Baker1, and B.J. Thomson2; 1Department of Geology, Mercyhurst University, Erie, PA 16546 ([email protected]), 2Department of Earth and Planetary Sciences, University of Tennessee – Knoxville, Knoxville, TN 37996 ([email protected]). Introduction: The Mahuea Tholus quadrangle (V- divided by major corona-associated flow fields that 49; Figure 1) extends from 25° to 50° S to 150° to continue into V-49. These flows are identified as the 180° E and encompasses >7×106 km2 of the Venusian central points of volcanism within the rift zone and surface. Moving clockwise from due north, the Ma- were used to help in determining stratigraphy. There huea Tholus quadrangle is bounded by the Diana are four coronae present within the Diana-Dali Chasma Chasma, Thetis Regio, Artemis Chasma, Henie, Bar- in the map area: Agraulos, Annapuma, Colijnsplaat, rymore, Isabella, and Stanton quadrangles; together and Mayauel. Flow material from coronae outside of with Stanton, Mahuea Tholus is one of two remaining V-49 extend into this part of the map area adding fur- quadrangles to be geologically mapped in this part of ther complexity to the stratigraphy of this region. Tim- Venus. Here we report on our continued mapping of ing of fracture formation appears non-uniform with this quadrangle. Specifically, over the past year we NE-trending suites of fractures cross-cutting E-W have focused on refining the geology of the northern trending fracture suites; this suggests different parts of third of V-49 and mapping the distrubiton of small the rift zone were active at different times (stress re- volcanic edifices. -

Surface Processes in the Venus Highlands: Results from Analysis of Magellan and a Recibo Data

JOURNAL OF GEOPHYSICAL RESEARCH, VOL. 104, NO. E], PAGES 1897-1916, JANUARY 25, 1999 Surface processes in the Venus highlands: Results from analysis of Magellan and A recibo data Bruce A. Campbell Center for Earth and Planetary Studies, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C. Donald B. Campbell National Astronomy and Ionosphere Ceiitei-, Cornell University, Ithaca, New York Christopher H. DeVries Department of Physics and Astronomy, University of Massachusetts, Amherst Abstract. The highlands of Venus are characterized by an altitude-dependent change in radar backscattcr and microwave emissivity, likely produced by surface-atmosphere weathering re- actions. We analyzed Magellan and Arecibo data for these regions to study the roughness of the surface, lower radar-backscatter areas at the highest elevations, and possible causes for areas of anomalous behavior in Maxwell Montes. Arecibo data show that circular and linear radar polarization ratios rise with decreasing emissivity and increasing Fresnel reflectivity, supporting the hypothesis that surface scattering dominates the return from the highlands. The maximum values of these polarization ratios are consistent with a significant component of multiple-bounce scattering. We calibrated the Arecibo backscatter values using areas of overlap with Magellan coverage, and found that the echo at high incidence angles (up to 70") from the highlands is lower than expected for a predominantly diffuse scattering regime. This behavior may be due to geometric effects in multiple scattering from surface rocks, but fur- ther modeling is required. Areas of lower radar backscatter above an upper critical elevation are found to be generally consistent across the equatorial highlands, with the shift in micro- wave properties occurring over as little as 5ÜÜ m of elevation. -

Global Tectonics of Terrestrial Planets Laurent Montesi University of Maryland

Melas Dorsa, Solis Planum, Mars (HRSC) Global Tectonics of Terrestrial Planets Laurent Montesi University of Maryland CIDER 2014 Marc WieczorekCIDER 2014 Marc WieczorekCIDER 2014 Marc WieczorekCIDER 2014 Global tectonics on Earth Strain rate map (Corné Kremeer) http://gsrm.unavco.org/ CIDER 2014 Recognizing Plate Tectonics • Rigid interior / • Divergent motion deformable boundaries • Normal faults • Linear belts of activity • Rift morphology with • Earthquakes volcanism • Volcanoes • Convergent motion • Topography • Differentiated volcanism • Faults • Accretionary wedges • Plate interior • Coherent motion • High-grade • Reconstructions metamorphism • Geodesy • Strike-slip motion • Negligible current • Horizontal offsets activity • Limited volcanism GEOL412/789A – Lecture 07 Planetary Observables Earth Mars Venus Distribution of earthquakes Soon (InSight) Not available Distribution of volcanism Yes Yes Composition Hypsometry Hypsometry Flow morphology Flow morphology Surface composition Surface composition Samples Remote sensing Faulting Visible images Radar images Topography Laser altimetry (global) Radar altimetry (global) Interferometry (local) Interferometry (local) Geodesy Not available Not available Ages Cratering (coarse) Cratering (coarse) Geological units Yes Yes Geoid Yes Yes Heat flux Soon (InSight) Not available Resources • Google Earth • Google Mars http://www.google.com/mars Native to Google Earth (also Google Moon and Google Sky) • Google Venus (under development from Scripps and Google) • ftp://topex.ucsd.edu/pub/sandwell/google_venus/Google_Venus.kmz -

1 : 45 000 000 E a CORONA D T N O M E Or E ASPASIA T Sa MM= KM S R

N N 80° 80° 80° Dennitsa D. 80° Y LO S Sz um U N éla yn H EG nya -U I BACHUE URO IA D d P ANAHIT CHKA PLANIT ors Klenova yr L CORONA M POMONA a D A ET CORONA o N Renpet IS r I R CORONA T sa T Mons EG FERONIA ET L I I H A . Thallo O A U u Tünde CORONA F S k L Mons 60° re R 60° 60° R a 60° . y j R E e u M Ivka a VACUNA GI l m O k . es E Allat Do O EARHART o i p e Margit N OTAU nt M T rsa CORONA a t a D E o I R Melia CORONA n o r o s M M .Wanda S H TA D a L O CORONA a n g I S Akn Mons o B . t Y a x r Mokosha N Rita e w U E M e A AUDRA D s R V s E S R l S VENUS FAKAHOTU a Mons L E E A l ES o GI K A T NIGHTINGALE I S N P O HM Cleopatra M RTUN A VÉNUSZ VENERA CORONA r V I L P FO PLANITIA ÂÅÍÅÐÀ s A o CORONA M e LA N P N n K a IT MOIRA s UM . a Hemera Dorsa A Iris DorsaBarsova 11 km a E IA TESSERA t t m A e a VENUŠE WENUS Hiei Chu n R a r A R E s T S DEMETER i A d ES D L A o Patera A r IS T N o R s r TA VIRIL CORONA s P s u e a L A N I T I A P p nt A o A L t e o N s BEIWE s M A ir u K A D G U Dan Baba-Jaga 1 : 45 000 000 E a CORONA D T N o M e or E ASPASIA t sa MM= KM S r . -

Astronomer's Computer Companion / Jeff Foust and Ron Lafon

astronomer’s computer companion Jeff Foust &Ron LaFon San Francisco the astronomer’s computer companion. Copyright by Jeff Foust and Ron LaFon All rights reserved. No part of this work may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any informa- tion storage or retrieval system, without the prior written permission of the copyright owner and the publisher. Printed in the United States of America c Printed on recycled paper — Trademarks Trademarked names are used throughout this book. Rather than use a trademark symbol with every occurrence of a trademarked name, we are using the names only in an editorial fashion and to the benefit of the trademark owner, with no intention of infringement of the trademark. :William Pollock :Karol Jurado :Derek Yee Design :Derek Yee :Margery Cantor copyeditors:Gail Nelson, Judy Ziajka :John Carroll :Nancy Humphreys Distributed to the book trade in the United States and Canada by Publishers Group West, Fourth Street, Berkeley, California , phone: --or --, fax: --. For information on translations or book distributors outside the United States, please contact No Starch Press directly: No Starch Press China Basin Street, Suite , San Francisco, CA - phone: --; fax: --; [email protected]; www.nostarch.com The information in this book is distributed on an “As Is” basis, without warranty. While every precaution has been taken in the preparation of this work, neither the author nor No Starch Press shall have any liability to any person or entity with respect to any loss or damage caused or alleged to be caused directly or indirectly by the information contained in it. -

Lithospheric Structure of Venus from Gravity and Topography

1 Lithospheric structure of Venus from gravity and topography Alberto Jiménez-Díaz a, b,*, Javier Ruiz a, Jon F. Kirby c Ignacio Romeo a, Rosa Tejero a, b, Ramón Capote a a Departamento de Geodinámica, Facultad de Ciencias Geológicas, Universidad Complutense de Madrid. 28040 Madrid, Spain b Instituto de Geociencias, IGEO (CSIC,UCM). 28040 Madrid, Spain c Department of Spatial Sciences, Curtin University, GPO Box U1987, Perth WA 6845, Australia * Corresponding author: Alberto Jiménez-Díaz Departamento de Geodinámica, Facultad de CC. Geológicas, Universidad Complutense de Madrid. c/ José Antonio Novais, 12. 28040 Madrid (Spain) Tel: +34 91 394 4821; Fax: +34 91 394 4845. E-mail address: [email protected] 2 Abstract There are many fundamental and unanswered questions on the structure and evolution of the Venusian lithosphere, which are key issues for understanding Venus in the context of the origin and evolution of the terrestrial planets. Here we investigate the lithospheric structure of Venus by calculating its crustal and effective elastic thicknesses (Tc and Te, respectively) from an analysis of gravity and topography, in order to improve our knowledge of the large scale and long-term mechanical behaviour of its lithosphere. We find that the Venusian crust is usually 20-25 km thick with thicker crust under the highlands. Our effective elastic thickness values range between 14 km (corresponding to the minimum resolvable Te value) and 94 km, but are dominated by low to moderate values. Te variations deduced from our model could represent regional variations in the cooling history of the lithosphere and/or mantle processes with limited surface manifestation. -

Bond 210X275 Chimie Atkins Jones 11/09/2014 09:47 Page1

Bond 210X275_chimie_atkins_jones 11/09/2014 09:47 Page1 Bond Bond L’exploration du système solaire Bond L’exploration Édition française revue et corrigée La planétologie à vivre comme un roman Exploration du système solaire est la première traduction policier actualisée et corrigée en français d’Exploring the Solar Destiné aux lecteurs et étudiants ne possédant que peu du système solaire System. Le traducteur a collaboré avec l’auteur pour ou pas de connaissances scientifiques, cet ouvrage très apporter plus de 70 mises à jour dont 7 nouvelles images. richement illustré prouve que la planétologie peut être racontée comme un roman policier, pratiquement sans Beau comme un livre d’art mathématiques. Les nombreuses illustrations en couleur montrent la vie quo- tidienne des mondes étranges et fascinants de notre petit Entre mille autres exemples, on y apprend : coin de l’Univers. À partir des plus récentes découvertes de Où se placer pour admirer deux couchers de Soleil par jour l’exploration du Système Solaire, Peter Bond offre un panora- sur Mercure, la planète de roche et de fer, brûlante d’un côté ma exhaustif et exemplaire des planètes, lunes et autres et congelée de l’autre ; comment détecter un océan d’eau Traduction de Nicolas Dupont-Bloch petits corps en orbite autour du Soleil et des étoiles proches. salée sur une lune de Saturne, protégé de l’espace par une banquise qui, sans cesse, se fracture, laisse fuser des geysers, Une exploration surprenante puis regèle ; pourquoi Vénus tourne à l’envers ; comment on Le texte, riche mais limpide, est ponctué d’anecdotes sur déduit qu’une planète autour d’une autre étoile possède une les hasards des découvertes, les trésors d’ingéniosité pour surface de goudron percée de montagnes de graphite.