SFRA Newsletter, 186, April 1991

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The 2021 Guide to Manuscript Publishers

Publish Authors Emily Harstone Authors Publish The 2021 Guide to Manuscript Publishers 230 Traditional Publishers No Agent Required Emily Harstone This book is copyright 2021 Authors Publish Magazine. Do not distribute. Corrections, complaints, compliments, criticisms? Contact [email protected] More Books from Emily Harstone The Authors Publish Guide to Manuscript Submission Submit, Publish, Repeat: How to Publish Your Creative Writing in Literary Journals The Authors Publish Guide to Memoir Writing and Publishing The Authors Publish Guide to Children’s and Young Adult Publishing Courses & Workshops from Authors Publish Workshop: Manuscript Publishing for Novelists Workshop: Submit, Publish, Repeat The Novel Writing Workshop With Emily Harstone The Flash Fiction Workshop With Ella Peary Free Lectures from The Writers Workshop at Authors Publish The First Twenty Pages: How to Win Over Agents, Editors, and Readers in 20 Pages Taming the Wild Beast: Making Inspiration Work For You Writing from Dreams: Finding the Flashpoint for Compelling Poems and Stories Table of Contents Table of Contents .......................................................................................................... 5 Introduction ................................................................................................................. 13 Nonfiction Publishers.................................................................................................. 19 Arcade Publishing .................................................................................................. -

FANTASY FAIRE 19 81 of Fc Available for $4.00 From: TRISKELL PRESS P

FANTASY FAIRE 19 81 of fc Available for $4.00 from: TRISKELL PRESS P. 0. Box 9480 Ottawa, Ontario Canada K1G 3V2 J&u) (B.Mn'^mTuer KOKTAL ADD IHHOHTAl LOVERS TRAPPED Is AS ASCIEST FEUD... 11th ANNUAL FANTASY FAIRS JULY 17, 18, 19, 1981 AMFAC HOTEL MASTERS OF CEREMONIES STEPHEN GOLDIN, KATHLEEN SKY RON WILSON CONTENTS page GUEST OF HONOR ... 4 ■ GUEST LIST . 5 WELCOME TO FANTASY FAIRE by’Keith Williams’ 7 PROGRAM 8 COMMITTEE...................... .. W . ... .10 RULES FOR BEHAVIOR 10 WALKING GUIDE by Bill Conlln 12 MAP OF AREA ........................................................ UPCOMING FPCI CONVENTIONS 14 ADVERTISERS Triskell Press Barry Levin Books Pfeiffer's Books & Tiques Dangerous Visions Cover Design From A Painting By Morris Scott Dollens GUEST OF HONOR FRITZ LEIBER was bom in 1910. Son of a Shakespearean actor, Fritz was at one time an actor himself and a mem ber of his father’s troupe. He made a cameo appearance in the film "Equinox." Fritz has studied many sciences and was once editor of Science Digest. His writing career began prior to World War 11 with some stories in Weird Tales. Soon Unknown published his novel "Conjure Wife, " which was made into a movie under the title (of all things) "Bum, Witch, Bum!" His Gray Mouser stories (which were the inspira tion for the Fantasy Faire "Fritz Leiber Fantasy Award") were started in Unknown and continued in Fantastic, which magazine devoted its entire Nov., 1959 issue to Fritz's stories. In 1959 Fritz was awarded a Hugo, by the World Science Fiction Convention for his novel "The Big Time." His novel "The Wanderer," about an interloper into our solar system, won the Hugo again in 1965.'-His novelettes Gonna Roll the Bones," "Ship of Shadows" and "Ill Met in Lankhmar” won the Hugo in 1968, 1970 and 1971 in that order. -

Models of Time Travel

MODELS OF TIME TRAVEL A COMPARATIVE STUDY USING FILMS Guy Roland Micklethwait A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of The Australian National University July 2012 National Centre for the Public Awareness of Science ANU College of Physical and Mathematical Sciences APPENDIX I: FILMS REVIEWED Each of the following film reviews has been reduced to two pages. The first page of each of each review is objective; it includes factual information about the film and a synopsis not of the plot, but of how temporal phenomena were treated in the plot. The second page of the review is subjective; it includes the genre where I placed the film, my general comments and then a brief discussion about which model of time I felt was being used and why. It finishes with a diagrammatic representation of the timeline used in the film. Note that if a film has only one diagram, it is because the different journeys are using the same model of time in the same way. Sometimes several journeys are made. The present moment on any timeline is always taken at the start point of the first time travel journey, which is placed at the origin of the graph. The blue lines with arrows show where the time traveller’s trip began and ended. They can also be used to show how information is transmitted from one point on the timeline to another. When choosing a model of time for a particular film, I am not looking at what happened in the plot, but rather the type of timeline used in the film to describe the possible outcomes, as opposed to what happened. -

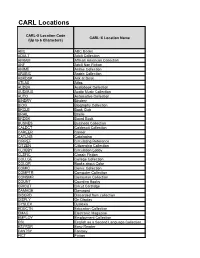

CARL Locations

CARL Locations CARL•X Location Code CARL•X Location Name (Up to 6 Characters) ABC ABC Books ADULT Adult Collection AFRAM African American Collection ANF Adult Non Fiction ANIME Anime Collection ARABIC Arabic Collection ASKDSK Ask at Desk ATLAS Atlas AUDBK Audiobook Collection AUDMUS Audio Music Collection AUTO Automotive Collection BINDRY Bindery BIOG Biography Collection BKCLB Book Club BRAIL Braille BRDBK Board Book BUSNES Business Collection CALDCT Caldecott Collection CAREER Career CATLNG Cataloging CIRREF Circulating Reference CITZEN Citizenship Collection CLOBBY Circulation Lobby CLSFIC Classic Fiction COLLGE College Collection COLOR Books about Color COMIC Comic Collection COMPTR Computer Collection CONSMR Consumer Collection COUNT Counting Books CRICUT Cricut Cartridge DAMAGE Damaged DISCRD Discarded from collection DISPLY On Display DYSLEX Dyslexia EDUCTN Education Collection EMAG Electronic Magazine EMPLOY Employment Collection ESL English as a Second Language Collection ESYRDR Easy Reader FANTSY Fantasy FICT Fiction CARL•X Location Code CARL•X Location Name (Up to 6 Characters) GAMING Gaming Collection GENEAL Genealogy Collection GOVDOC Government Documents Collection GRAPHN Graphic Novel Collection HISCHL High School Collection HOLDAY Holiday HORROR Horror HOURLY Hourly Loans for Pontiac INLIB In Library INSFIC Inspirational Fiction INSROM Inspirational Romance INTFLM International Film INTLNG International Language Collection JADVEN Juvenile Adventure JAUDBK Juvenile Audiobook Collection JAUDMU Juvenile Audio Music Collection -

SHAMAR's WAR the STAR KING OH, to BE'a-Btubel JACK VANCE

FEBRUARY SHAMAR’S WAR THE STAR KING OH, TO BE'A-BtuBEL by by by KRIS NEVILLE JACK VANCE PHILIP K. DICK A New Complete Novelette 1964 GRANDMOTHER A New EARTH Complete by J. Novelette T. MdNTQSH DON’T CLIP THE COUPON- — if you want to keep your copy of Galaxy intact for permanent possession!* Why mutilate a good thing? But, by the same token... if you're devotee enough to want to keep your copies in mint condition, you ought to subscribe. You really ought to. For one thing, you get your copies earlier. For another, you’re sure you'll get them! Sometimes newsstands run out — the mail never does. (And you can just put your name and address on a plain sheet of paper and mail it to us, at the address below. We’ll know what you mean... provided you enclose your check!) In the past few years Galaxy has published the finest stories by the finest writers in the field - Bester, Heinlein, Pohl, Asimov, Sturgeon, Leiber and nearly everyone else. In the next few years it will go right on, with stories that are just as good ... or better. Don’t miss any issue of Galaxy. You can make sure you won’t. Just subcribe today. *(lf, on the other hand, your habit is to read them once and go on to something new - please - feel free to use the coupon! It’s for your convenience, not ours.) U GALAXY Publishing Corp., 421 Hudson Street, New York 14, N. Y. (50c additional per 6 issues Enter my subscription for the New Giant 196-page Galaxy foreign postage) (U. -

New Pulp-Related Books and Periodicals Available from Michael Chomko for July 2008

New pulp-related books and periodicals available from Michael Chomko for July 2008 In just two short weeks, the Dayton Convention Center will be hosting Pulpcon 37. It will begin on Thursday, July 31 and run through Sunday, August 3. This year’s convention will focus on Jack Williamson and the 70 th anniversary of John Campbell’s ascension to the editorship of Astounding. There will be two guests-of-honor, science-fiction writers Larry Niven and Jerry Pournelle. Another highlight will be this year’s auction. It will feature many items from the estate of Ed Kessell, one of the guiding lights of the first Pulpcon. Included will be letters signed by Walter Gibson, E. Hoffmann Price, Walter Baumhofer, and others, as well as a wide variety of pulp magazines. For further information about Pulpcon 37, please visit the convention’s website at http://www.pulpcon.org/ Another highlight of Pulpcon is Tony Davis’ program book and fanzine, The Pulpster . As usual, I’ll be picking up copies of the issue for those of you who are unable to attend the convention. If you’d like me to acquire a copy for you, please drop me an email or letter as soon as possible. My addresses are listed below. Most likely, the issue will cost about seven dollars plus postage. For those who have been concerned, John Gunnison of Adventure House will be attending Pulpcon. If you plan to be at Pulpcon and would like me to bring along any books that I am holding for you, please let me know by Friday, July 25. -

Visual Representations of Terry Pratchett's Discworld in Time And

IMAGINATIONS: JOURNAL OF CROSS-CULTURAL IMAGE STUDIES | REVUE D’ÉTUDES INTERCULTURELLES DE L’IMAGE Publication details, including open access policy and instructions for contributors: http://imaginations.glendon.yorku.ca Visibility and Translation Guest Editor: Angela Kölling December 31, 2020 Image Credit: Cia Rinne, Das Erhabene (2011) To cite this article: Sohár, Anikó. “Each to Their Own: Visual Representations of Terry Pratchett’s Discworld in Time and Space.” Imaginations: Journal of Cross-Cultural Image Studies, vol. 11, no. 3, Dec. 2020, pp. 123-163, doi: 10.17742/IMAGE.VT.11.3.6. To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.17742/IMAGE.VT.11.3.6 The copyright for each article belongs to the author and has been published in this journal under a Creative Commons 4.0 International Attribution NonCommercial NoDerivatives license that allows others to share for non-commercial purposes the work with an acknowledgement of the work’s authorship and initial publication in this journal. The content of this article represents the author’s original work and any third-party content, either image or text, has been included under the Fair Dealing exception in the Canadian Copyright Act, or the author has provided the required publication permissions. Certain works referenced herein may be separately licensed, or the author has exercised their right to fair dealing under the Canadian Copyright Act. EACH TO THEIR OWN: VISUAL REPRESENTATIONS OF TERRY PRATCHETT’S DISCWORLD IN TIME AND SPACE ANIKÓ SOHÁR When a book is translated, publishers Lorsqu’un livre est traduit, les éditeurs mo- will often modify or completely change difient souvent, voire changent complète- the cover design. -

Congratulations Susan & Joost Ueffing!

CONGRATULATIONS SUSAN & JOOST UEFFING! The Staff of the CQ would like to congratulate Jaguar CO Susan and STARFLEET Chief of Operations Joost Ueffi ng on their September wedding! 1 2 5 The beautiful ceremony was performed OCT/NOV in Kingsport, Tennessee on September 2004 18th, with many of the couple’s “extended Fleet family” in attendance! Left: The smiling faces of all the STARFLEET members celebrating the Fugate-Ueffi ng wedding. Photo submitted by Wade Olsen. Additional photos on back cover. R4 SUMMIT LIVES IT UP IN LAS VEGAS! Right: Saturday evening banquet highlight — commissioning the USS Gallant NCC 4890. (l-r): Jerry Tien (Chief, STARFLEET Shuttle Ops), Ed Nowlin (R4 RC), Chrissy Killian (Vice Chief, Fleet Ops), Larry Barnes (Gallant CO) and Joe Martin (Gallant XO). Photo submitted by Wendy Fillmore. - Story on p. 3 WHAT IS THE “RODDENBERRY EFFECT”? “Gene Roddenberry’s dream affects different people in different ways, and inspires different thoughts... that’s the Roddenberry Effect, and Eugene Roddenberry, Jr., Gene’s son and co-founder of Roddenberry Productions, wants to capture his father’s spirit — and how it has touched fans around the world — in a book of photographs.” - For more info, read Mark H. Anbinder’s VCS report on p. 7 USPS 017-671 125 125 Table Of Contents............................2 STARFLEET Communiqué After Action Report: R4 Conference..3 Volume I, No. 125 Spies By Night: a SF Novel.............4 A Letter to the Fleet........................4 Published by: Borg Assimilator Media Day..............5 STARFLEET, The International Mystic Realms Fantasy Festival.......6 Star Trek Fan Association, Inc. -

Ted Chiang Story of Your Life and Ot

Ted chiang story of your life and ot Continue Soon there will be a major film starring Amy Adams. This new edition of Ted Chang's masterful first collection, Stories of Your Life and Others, includes his first eight published short stories plus the author's story notes, and the cover that the author commissioned himself. Combining the precision and scientific curiosity of Kim Stanley Robinson with Lorry Moore's cool, clear love of language and narrative subtlety, this award-winning collection offers readers the dual charms of a very, very strange and heartbreakingly familiar. The stories of your life and others represent characters that must withstand sudden changes - the inevitable rise of automatons or the appearance of aliens - while striving to maintain some sense of normality. In an amazing and highly acclaimed title story, a grieving mother copes with her daughter's divorce and death, drawing on her knowledge of alien languages and non-linear memories of memory. Smart pastiche news and interviews chronicle the college's initiative to turn off a person's ability to recognize beauty in Love What You See: A Documentary. With sharp intelligence and humor, Chan examines what it means to be alive in a world marked by uncertainty and constant change, as well as beauty and wonder. Ted Chang is one of the most celebrated science fiction authors writing today and is the author of numerous short stories, including most recently Exhale, which won hugo, British science fiction and the Locus Awards. He lives near Seattle. An award-winning book from the author of Exhale, this collection of short stories mix absorbing narrative with reflections on the universe, existence, time and space . -

The Apocalyptic Book List

The Apocalyptic Book List Presented by: The Post Apocalyptic Forge Compiled by: Paul Williams ([email protected]) As with other lists compiled by me, this list contains material that is not strictly apocalyptic or post apocalyptic, but that may contain elements that have that fresh roasted apocalyptic feel. Because I have not read every single title here and have relied on other peoples input, you may on occasion find a title that is not appropriate for the intended genre....please do let me know and I will remove it, just as if you find a title that needs to be added...that is appreciated as well. At the end of the main book list you will find lists for select series of books. Title Author 8.4 Peter Hernon 905 Tom Pane 2011, The Evacuation of Planet Earth G. Cope Schellhorn 2084: The Year of the Liberal David L. Hale 3000 Ad : A New Beginning Jon Fleetwood '48 James Herbert Abyss, The Jere Cunningham Acts of God James BeauSeigneur Adulthood Rites Octavia Butler Adulthood Rites, Vol. 2 Octavia E. Butler Aestival Tide Elizabeth Hand Afrikorps Bill Dolan After Doomsday Poul Anderson After the Blue Russel C. Like After the Bomb Gloria D. Miklowitz After the Dark Max Allan Collins After the Flames Elizabeth Mitchell After the Flood P. C. Jersild After the Plague Jean Ure After the Rain John Bowen After the Zap Michael Armstrong After Things Fell Apart Ron Goulart After Worlds Collide Edwin Balmer, Philip Wylie Aftermath Charles Sheffield Aftermath K. A. Applegate Aftermath John Russell Fearn Aftermath LeVar Burton Aftermath, The Samuel Florman Aftershock Charles Scarborough Afterwar Janet Morris Against a Dark Background Iain M. -

Progress Report 1 Emma Bull & Will Shetterly Arthur Hlavaty Rick

Minicon 37 P.O. Box 8297 Lake Street Station Minneapolis, MN 55408 Progress Re g i s t r ation deadline has been Report 1 mo ved toNew Years Eve! M a rch 29-31, 2002 at the Hilton Minneapolis in Minneapolis, Minnesota Yes Virginia, there will be a Minicon Writer Guests of Honor: Minicon is a gathering of science fiction and fantasy fans sponsored by the Minnesota Science Fiction Society Emma Bull (Minn-StF). The convention is held each year in (or near) Minneapolis, over Easter weekend. &Will Shetterly Of course, that description doesn't quite do the conven t i o n Fan Guest of Honor: justice. What is Minicon? A gathering of friends (some of whom you haven't met yet) and so much more. Last yea r Arthur Hlavaty Minicon encompassed a rocket garden, a cocktail party, bozo noses, our own version of Ju n k yard War s (but on Artist Guest of Honor: a smaller scale), interesting discussions about books and science and stuff, a trivia contest, Mardi Gras masks, some Rick Berry amazing music parties, a concert, an art show, a hucks t e r ' s room, tasty (and, um, interesting) food and drink, hall RATES: ADULT CHILD SUPPORTING costumes, room parties, and that's just the beginning. Until New Years Eve (1 2 / 3 1 / 0 1 ) : $3 0 $1 5 $1 5 What can you expect this year? Fun: we'll provide wha t Until Valentines Day (2 / 1 4 / 0 2 ) : $4 5 $1 5 $1 5 we can, and we expect you to bring your own. -

The Founder Effect

Baen Books Teacher Guide: The Founder Effect Contents: o recommended reading levels o initial information about the anthology o short stories grouped by themes o guides to each short story including the following: o author’s biography as taken from the book itself o selected vocabulary words o content warnings (if any) o short summary o selected short assessment questions o suggested discussion questions and activities Recommended reading level: The Founder Effect is most appropriate for an adult audience; classroom use is recommended at a level no lower than late high school. Background: Published in 2020 by Baen Books, The Founder Effect tackles the lens of history on its subjects—both in their own words and in those of history. Each story in the anthology tells a different part of the same world’s history, from the colonization project to its settlement to its tragic losses. The prologue provides a key to the whole book, serving as an introduction to the fictitious encyclopedia and textbook entries which accompany each short story. Editors’ biographies: Robert E. Hampson, Ph.D., turns science fiction into science in his day job, and puts the science into science fiction in his spare time. Dr. Hampson is a Professor of Physiology / Pharmacology and Neurology with over thirty-five years’ experience in animal neuroscience and human neurology. His professional work includes more than one hundred peer-reviewed research articles ranging from the pharmacology of memory to the first report of a “neural prosthetic” to restore human memory using the brain’s own neural codes. He consults with authors to put the “hard” science in “Hard SF” and has written both fiction and nonfiction for Baen Books.