1 the Commodity Frontier by Arlie Russell Hochschild in Self, Social

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

November 1998

April 2020 Curriculum Vitae Annette Lareau Edmund J. and Louise W. Kahn Endowed Term Professor in the Social Sciences Department of Sociology University of Pennsylvania 3718 Locust Walk, McNeil Building, Ste. 113 Philadelphia, PA 19104-6299 215 898-3515 (phone) 215 573-2081 (fax) Email: [email protected] EDUCATION 1984 Ph.D., Sociology, University of California, Berkeley 1978 M.A., Sociology, University of California, Berkeley 1974 B.A., Sociology, with Highest honors, University of California, Santa Cruz AWARDS 2004 William J. Goode, Best Book in Sociology of the Family, Unequal Childhoods, American Sociological Association Culture Section, Co-winner of Best Book Award, Unequal Childhoods, American Sociological Association Section on Childhood and Youth, Distinguished Scholarship Award for Unequal Childhoods, American Sociological Association Finalist, C. Wright Mills Prize, Unequal Childhoods, Society for the Study of Social Problems AESA Critics Choice Award, Unequal Childhoods, American Educational Studies Association 1991 Willard Waller Award for Distinguished Scholarship, Home Advantage, Sociology of Education Section, American Sociological Association. AESA Critics Choice Award, Home Advantage, American Educational Studies Association PUBLICATIONS: BOOKS 2018 Ritual, Emotion, Violence: Studies on the Micro-Sociology of Randall Collins. (Edited by Elliot Weininger, Annette Lareau, and Omar Lizardo). New York: Routledge. 2014 Choosing Homes, Choosing Schools. (Edited by Annette Lareau and Kimberly Goyette.) New York: The Russell Sage Foundation. 2011 Unequal Childhoods: Race, Class, and Family Life. Second Edition. A Decade Later. University of California Press. [2011/2003] Translated into Chinese, Korean, and Spanish. Reprinted (selections): American Families (Ed. By Stephanie Coontz, Routledge, 2008, 400-417. 2009 Educational Research on Trial. (Edited by Pamela Barnhouse Walters, Annette Lareau, and Sherri Ranis). -

Immigration Policymaking in the Newest Era of Nativist Populism

IN SEARCH OF A NEW EQUILIBRIUM: IMMIGRATION POLICYMAKING IN THE NEWEST ERA OF NATIVisT POPULisM By Demetrios G. Papademetriou, Kate Hooper, and Meghan Benton TRANSATLANTIC COUNCIL ON MIGRATION IN SEARCH OF A NEW EQUILIBRIUM Immigration Policymaking in the Newest Era of Nativist Populism By Demetrios G. Papademetriou, Kate Hooper, and Meghan Benton November 2018 Acknowledgments This research was commissioned for the eighteenth plenary meeting of the Transatlantic Council on Migration, an initiative of the Migration Policy Institute (MPI), held in Stockholm in November 2017. The meeting’s theme was “The Future of Migration Policy in a Volatile Political Landscape,” and this report was one of several that informed the Council’s discussions. The authors are grateful for Lauren Shaw’s helpful edits and for research assistance from Brian Salant, Gonzaga Mbalungu, Jeffrey Hallock, and Jae June Lee. The Council is a unique deliberative body that examines vital policy issues and informs migration policymaking processes in North America and Europe. The Council’s work is generously supported by the following foundations and governments: the Open Society Foundations, Carnegie Corporation of New York, the Barrow Cadbury Trust, the Luso- American Development Foundation, the Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation, and the governments of Germany, the Netherlands, Norway, and Sweden. For more on the Transatlantic Council on Migration, please visit: www.migrationpolicy.org/ transatlantic. © 2018 Migration Policy Institute. All Rights Reserved. Cover Design: April Siruno, MPI Layout: Sara Staedicke, MPI No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission from the Migration Policy Institute. -

Don't Worry, Be Happy

Don’t worry, be happy. - A study of how unaccompanied refugee minors in a Norwegian refugee reception centre deal with emotions Stig Rune Aasheim Molvik February 2009 - Master’s thesis Department of Sociology and Human Geography Faculty of Social Sciences University of Oslo II There is this little song I wrote I hope you learn it note for note Like good little children Don't worry, be happy Listen to what I say In your life expect some trouble But when you worry You make it double Don't worry, be happy...... Don't worry don't do it, be happy Put a smile on your face Don't bring everybody down like this Don't worry, it will soon past Whatever it is Don't worry, be happy Verse from ‘Don’t worry, be happy’ by Bobby McFerrin III IV Acknowledgements Writing this thesis has been a long and winding road, as the song goes. On my way I have met many people that have inspired and helped me, that I owe my deep respect and thanks. First and foremost I want to thank the unaccompanied refugee minors that I have met in the course of this thesis. You have truly been an inspiration in so many ways, and I am ever so grateful for the kind welcome and hospitality you have shown me during my time with you. A special thanks to those minors that shared their personal thoughts and experiences with me. I also want to thank the reception centre staff, the minors’ teachers, and the minors’ guardians, for letting me talk to you and the minors, for helping me and for sharing your insight into these minors’ lives, and for all the good work you do. -

1 Curriculum Vitae Arlie Russell Hochschild

Curriculum Vitae Arlie Russell Hochschild Personal Work Address Sociology Department University of California, Berkeley Berkeley, California 94720 Home Address 2353 Vine Street Berkeley, California 94708 Married to Adam Hochschild (1965), two children, David and Gabriel. Education Ph.D., 1969, Sociology, University of California, Berkeley M.A., 1965, Sociology, University of California, Berkeley B.A., 1962, International Relations, Swarthmore College Academic Appointments 2006 – Present Full Professor of the Graduate School, University of California, Berkeley 1983 – 2006 Full Professor, Department of Sociology, UC Berkeley 1997 – 2001 Director, Center for Working Families, University of California, Berkeley 1999 – 2001 Co-Director, Center for Working Families, with Professor Barrie Thorne. 1992 (Fall) Lang Visiting Professor, Swarthmore College. 1975 – 1983 Associate Professor, Department of Sociology, UC Berkeley 1978 – 1979 Acting Chair, Sociology Department, University of California, Berkeley 1971 – 1975 Assistant Professor, Department of Sociology, UC Berkeley 1969 – 1971 Assistant Professor, University of California, Santa Cruz Awards, Honors and Grants Honorary Degrees Honorary Doctor of Philosophy, Mount Saint Vincent University, Canada (2013) Honorary Doctor of Philosophy, University of Lapland, Finland (2012) Honorary Doctor of Philosophy, Aalborg University, Denmark (2004) Honorary Doctor of Philosophy, University of Oslo, Norway (2000) Honorary Doctor of Philosophy, Swarthmore College (1993) Ulysses Medal, University College Dublin, Ireland (2015) Honorary Doctor of Philosophy, University of Lausanne (2018) Honorary Doctor of Philosophy, Westminster University (2018) 1 Research Grants Ford Foundation, grant for research on work-family policies reported in The Time Bind (1990-1991) Alfred P. Sloan Foundation grant to establish a Center for Working Families at University of California, Berkeley, to train scholars in qualitative research on working families ($3,000,000; 1997). -

The American Middle Class, Income Inequality, and the Strength of Our Economy New Evidence in Economics

The American Middle Class, Income Inequality, and the Strength of Our Economy New Evidence in Economics Heather Boushey and Adam S. Hersh May 2012 WWW.AMERICANPROGRESS.ORG The American Middle Class, Income Inequality, and the Strength of Our Economy New Evidence in Economics Heather Boushey and Adam S. Hersh May 2012 Contents 1 Introduction and summary 9 The relationship between a strong middle class, the development of human capital, a well-educated citizenry, and economic growth 23 A strong middle class provides a strong and stable source of demand 33 The middle class incubates entrepreneurs 39 A strong middle class supports inclusive political and economic institutions, which underpin growth 44 Conclusion 46 About the authors 47 Acknowledgements 48 Endnotes Introduction and summary To say that the middle class is important to our economy may seem noncontro- versial to most Americans. After all, most of us self-identify as middle class, and members of the middle class observe every day how their work contributes to the economy, hear weekly how their spending is a leading indicator for economic prognosticators, and see every month how jobs numbers, which primarily reflect middle-class jobs, are taken as the key measure of how the economy is faring. And as growing income inequality has risen in the nation’s consciousness, the plight of the middle class has become a common topic in the press and policy circles. For most economists, however, the concepts of “middle class” or even inequal- ity have not had a prominent place in our thinking about how an economy grows. This, however, is beginning to change. -

Managed Heart : Commercialization of Human Feeling, Update with a New Preface (3Rd Edition)

The Managed Heart Commercialization of Human Feeling Updated with a New Preface ARLIE RUSSELL HOCHSCHILD Q3 UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA PRESS Berkeley Los Angeles London The Managed Heart Other books by Arlie Russell Hochschild: The Second Shift: Working Couples and the Revolution at Home The Time Bind: When Work Becomes Home and Home Becomes Work Global Woman: Nannies, Maids and Sex Workers in the New Economy The Commercialization ofIntimate Life: Notes from Home and Work (UC Press) The Outsourced Self: Intimate Life in Market Times The Managed Heart Commercialization of Human Feeling Updated with a New Preface ARLIE RUSSELL HOCHSCHILD Q3 UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA PRESS Berkeley Los Angeles London University of California Press, one of the most distinguished university presses in the United States, enriches lives around the world by advancing scholarship in the humanities, social sciences, and natural sciences. Its activities are supported by the UC Press Foundation and by philanthropic contributions from individuals and institutions. For more information, visit www.ucpress.edu. University of California Press Berkeley and Los Angeles, California University of California Press, Ltd. London, England © 1983,2003,2012 by The Regents of the University of California First paperback printing 1985 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Hochschild, Arlie Russell, 1940-. The managed heart: commercialization of human feeling / Arlie Russell Hochschild. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-520-27294-1 (pbk. : alk. paper) 1. Emotions-Economic aspects. 2. Work-Psychological aspects. 3. Employee motivation. 1. Title. BF531.H62 2012 l52.4--dc21 2003042606 Manufactured in thc United States of America 20 19 18 17 16 15 14 13 12 10 9 8 7 6 543 2 The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of ANSI/NISO z39.48-1992 (R 2(02) (Pnmanence of Paper). -

Swarthmore College Bulletin (December 2002)

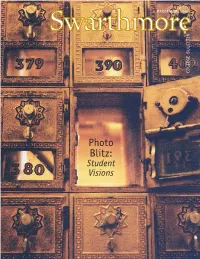

DECEMBER 2002 Photo Blitz: Student Visions ON THE COVER: B DAN FAIRCHILD’S [’03] PHOTOGRAPH OF PARRISH HALL MAILBOXES GRACES THE APRIL 2003 PAGE OF NEXT YEAR’S SWARTHMORE COLLEGE CALENDAR. IT IS ONE OF THOUSANDS OF PHOTOS SUBMITTED DURING THIS FALL’S “PHOTO BLITZ,” SPONSORED BY THE PUBLICATIONS OFFICE. FOR MORE STUDENT VISIONS OF SWARTHMORE, TURN TO PAGE 20. CONTENTS: HANG NGO ’05, ONE OF MORE THAN 360 STUDENTS WHO PARTICIPATED IN THE PHOTO BLITZ, SAID OF THIS PHOTO: “THE SHADOWS ARE [ONES] OF ME AND ... MY BEST FRIEND HERE, FRANCISCO CASTRO ’05 [LEFT].” DECEMBERDECEMBER 2002 2002 F e a t u r e s Cell Divisions 14 Swarthmore-educated scientists, ethicists, and legal scholars help Departments lead the stem-cell and cloning debate. L e t t e r s 3 Readers’ feedback By Tom Krattenmaker P r o f i l e s C o l l e c t i o n 4 Working Toward Through Student Current news a Better World 48 E y e s 2 0 Sam Ashelman ’37 hosted Bosnian A weeklong “Photo Blitz” reveals diplomats at Coolfont Resort.Resort students’ vision of Swarthmore. Alumni Digest 42 Connections and adventures By Elizabeth Redden ’05 By Jeffrey Lott ClassNotes 44 F o l l o w i n g Liberal Arts Correspondence from friends t h e W i n d 6 4 in a Conservative Jon Lyman ’77 enjoys the scenery L a n d 2 6 and sociability of ballooning. Two Swarthmoreans help start D e a t h s 5 3 a women’s college in Jeddah, Sympathy extended By Angela Doody Saudi Arabia. -

CSES Working Paper Series

Department of Sociology 327 Uris Hall Cornell University Ithaca, NY 14853-7601 CSES Working Paper Series Paper #12 Mabel Berezin "Emotions and the Economy" October 2003 Emotions and the Economy1 Prepared for: Handbook of Economic Sociology, 2nd edition, Neil J. Smelser and Richard Swedberg, eds. Forthcoming Russell Sage Foundation and Princeton University Press. Mabel Berezin Associate Professor of Sociology 354 Uris Hall Cornell University Ithaca, New York 14853 607-255-4042 [email protected] 1 I wish to acknowledge Neil Smelser’s cogent comments on the first version of this manuscript. The patience of both editors has greatly enhanced the final product. Brooke West provided able assistance with tracking down references. 2 The Return of Emotion Emotion and economy describes a relation that social scientists have only recently begun to acknowledge and valorize. Outside of various fields of psychology, sociologists and economists often treat emotions as residual categories. It is arguable that the project of modern social science from its European 19th century origins to its contemporary variations defines emotion out of social action in general and economic action in particular. In contrast to other contributions to this volume that discuss more or less established literatures, this chapter attempts to suggest plausible analytic frames that re- inscribe emotion in social and economic action. Even though strong, let alone competing, paradigms have not developed around emotion and economy, this pairing does not constitute an uncharted terrain. Emotions, rather than gone from sociological and economic analysis, have been more aptly in disciplinary exile. Multiple signs suggest that emotions are re-entering sociological and economic analysis. -

1 Curriculum Vitae Arlie Russell Hochschild Personal Work Address Sociology Department University of California, Berkeley Berkel

Curriculum Vitae Arlie Russell Hochschild Personal Work Address Sociology Department University of California, Berkeley Berkeley, California 94720 Home Address 2353 Vine Street Berkeley, California 94708 Married to Adam Hochschild (1965), two children, David and Gabriel. Education Ph.D., 1969, Sociology, University of California, Berkeley M.A., 1965, Sociology, University of California, Berkeley B.A., 1962, International Relations, Swarthmore College Academic Appointments 2006 – Present Full Professor of the Graduate School, University of California, Berkeley 1983 – 2006 Full Professor, Department of Sociology, UC Berkeley 1997 – 2001 Director, Center for Working Families, University of California, Berkeley 1999 – 2001 Co-Director, Center for Working Families, with Professor Barrie Thorne. 1992 (Fall) Lang Visiting Professor, Swarthmore College. 1975 – 1983 Associate Professor, Department of Sociology, UC Berkeley 1978 – 1979 Acting Chair, Sociology Department, University of California, Berkeley 1971 – 1975 Assistant Professor, Department of Sociology, UC Berkeley 1969 – 1971 Assistant Professor, University of California, Santa Cruz Awards, Honors and Grants Honorary Degrees Honorary Doctor of Laws, Harvard University, USA (2021) Honorary Doctor of Philosophy, Mount Saint Vincent University, Canada (2013) Honorary Doctor of Philosophy, University of Lapland, Finland (2012) Honorary Doctor of Philosophy, Aalborg University, Denmark (2004) Honorary Doctor of Philosophy, University of Oslo, Norway (2000) Honorary Doctor of Philosophy, Swarthmore College, USA (1993) Ulysses Medal, University College Dublin, Ireland (2015) Honorary Doctor of Philosophy, University of Lausanne (2018) Honorary Doctor of Philosophy, Westminster University (2018) 1 Research Grants Ford Foundation, grant for research on work-family policies reported in The Time Bind (1990-1991) Alfred P. Sloan Foundation grant to establish a Center for Working Families at University of California, Berkeley, to train scholars in qualitative research on working families ($3,000,000; 1997). -

Ugly Encounters in Scandinavian Au-Pair Novel

Elisabeth Oxfeldt “I Come from Crap Country and You Come from Luxury Country”: Ugly Encounters in Scandinavian Au-Pair Novels In the new millennium, the use of au pairs in the Scandinavian countries has increased steadily.1 Women hire au pairs because of a perceived time bind; without help, the woman in the Scandinavian household is likely to reduce her workload outside the home (Liversage, Bille, and Jakobsen 2013, 16). This may come as a surprise to those who have come to think of the Scandinavian countries as particularly happy and egalitarian. British journalist Helen Russell, for instance, decided to move to Denmark for a year to explore Danish happiness. Attending a language class, she finds herself surrounded by among others, half a dozen Filipino girls working as au pairs. Russell wonders: “’Isn’t everyone supposed to be equal in Denmark? Aren’t Danes supposed to do their own cleaning and child rearing?’” (2015, 69). The answer according to a 2013-report on the Danish au-pair program is “No”. Public institutions take care of children during work hours, and, increasingly, au pairs take care of house cleaning in general, and children during stressful moments at home, such as mornings and right before dinner (Liversage, Bille, and Jakobsen 2013, 16).2 As the report points out, this is far from unproblematic. While the term “au pair” suggests that the relationship between host family and au pair encompasses a cultural exchange between equals, in reality it is full of violations and grey areas.3 Subsequently, the au 1 In Denmark, for instance, the Au-Pair Convention (established by the European Council in 1969) was ratified in 1972. -

Interview with Arlie Russell Hochschild by Madalena D'oliveira-Martins

Sociologia, Problemas e Práticas 83 | 2017 SPP 83 Interview with Arlie Russell Hochschild by Madalena D’Oliveira-Martins Madalena d’Oliveira-Martins Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/spp/2660 ISSN: 2182-7907 Publisher Mundos Sociais Printed version Number of pages: 181-191 ISSN: 0873-6529 Electronic reference Madalena d’Oliveira-Martins, « Interview with Arlie Russell Hochschild by Madalena D’Oliveira-Martins », Sociologia, Problemas e Práticas [Online], 83 | 2017, Online since 06 February 2017, connection on 02 May 2019. URL : http://journals.openedition.org/spp/2660 © CIES - Centro de Investigação e Estudos de Sociologia INTERVIEW WITH ARLIE RUSSELL HOCHSCHILD BY MADALENA D’OLIVEIRA-MARTINS Madalena d’Oliveira-Martins Institute for Culture and Society, Pamplona, Spain Two years ago, I had the chance to do a research stay at Berkeley, and meet with sociologist Arlie Russell Hochschild for the first time. I was conducting research for my thesis and wanted to know more about Hochschild’s work and academic life; she graciously agreed to participate in an in-depth interview, which was con- ducted in Berkeley during February 2014 and updated and revised throughout January and May 2016. An abbreviated version was published in the Internatio- nal Sociological Association newsletter Global Dialogue in September 2014. Today, it seems of utmost importance to publish the complete interview with a comple- mentary update. Hochschild is one of the most distinguished sociologists of our time. Through her work on the sociology of emotions, the American sociologist explores the most urgent problems and challenges our societies face. Zooming in on subjects such as feminism, work-family balance, gender roles and the stalled revolutions surrounding them, feeling rules, emotion management and political emotions, Hochschild shows how her sociological eye on the issues of our time is reinforced by a joyful spirit and deep faith in the importance and effectiveness of social action. -

Provided by the Author(S) and University College Dublin Library in Accordance with Publisher Policies

Provided by the author(s) and University College Dublin Library in accordance with publisher policies. Please cite the published version when available. Title þÿAffective Equality as a Key Issue of Justice : A Comment on Fraser s 3-Dimensional Framework Authors(s) Lynch, Kathleen Publication date 2012-03 Series Social Justice Series; Vol. 12, No. 3 Publisher University College Dublin. School of Social Justice Item record/more information http://hdl.handle.net/10197/4400 Downloaded 2021-09-26T06:15:55Z The UCD community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters! (@ucd_oa) © Some rights reserved. For more information, please see the item record link above. Social Justice Series ________________________Article Vol. 12. No 3, March 2012: 45-64 Affective Equality as a Key Issue of Justice: A Comment on Fraser’s 3- Dimensional Framework Lynch, Kathleen University College Dublin, Ireland Abstract The relational realities of nurturing constitute a discrete site of social practice within and through which inequalities are created. The affective worlds of love, care and solidarity are therefore sites of political import that need to be examined in their own right while recognizing their inter-relatedness with economic, political and cultural systems in the generation of injustice. Drawing on extensive sociological research undertaken on care work, paid work and on education in a range of different studies, this paper argues that Fraser’s three- dimensional framework for analyzing injustice needs to expanded to include a fourth, relational dimension.The affective relations within which caring is grounded constitute a discrete field of social action within and through which inequalities and exploitations can occur.