International Seminar Harbour Cities

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Concise Ancient History of Indonesia.Pdf

CONCISE ANCIENT HISTORY OF INDONESIA CONCISE ANCIENT HISTORY O F INDONESIA BY SATYAWATI SULEIMAN THE ARCHAEOLOGICAL FOUNDATION JAKARTA Copyright by The Archaeological Foundation ]or The National Archaeological Institute 1974 Sponsored by The Ford Foundation Printed by Djambatan — Jakarta Percetakan Endang CONTENTS Preface • • VI I. The Prehistory of Indonesia 1 Early man ; The Foodgathering Stage or Palaeolithic ; The Developed Stage of Foodgathering or Epi-Palaeo- lithic ; The Foodproducing Stage or Neolithic ; The Stage of Craftsmanship or The Early Metal Stage. II. The first contacts with Hinduism and Buddhism 10 III. The first inscriptions 14 IV. Sumatra — The rise of Srivijaya 16 V. Sanjayas and Shailendras 19 VI. Shailendras in Sumatra • •.. 23 VII. Java from 860 A.D. to the 12th century • • 27 VIII. Singhasari • • 30 IX. Majapahit 33 X. The Nusantara : The other islands 38 West Java ; Bali ; Sumatra ; Kalimantan. Bibliography 52 V PREFACE This book is intended to serve as a framework for the ancient history of Indonesia in a concise form. Published for the first time more than a decade ago as a booklet in a modest cyclostyled shape by the Cultural Department of the Indonesian Embassy in India, it has been revised several times in Jakarta in the same form to keep up to date with new discoveries and current theories. Since it seemed to have filled a need felt by foreigners as well as Indonesians to obtain an elementary knowledge of Indonesia's past, it has been thought wise to publish it now in a printed form with the aim to reach a larger public than before. -

Eichhornia Crassipes) for Water Quality of Irrigation

Jr. of Industrial Pollution Control 32(1)(2016) pp 356-360 www.icontrolpollution.com Research THE PHYTOREMEDIATION TECHNOLOGY IN THE RECOVERY OF MERCURY POLLUTION BY USING WATER HYACINTH PLANT (EICHHORNIA CRASSIPES) FOR WATER QUALITY OF IRRIGATION 1 2 3 RUSNAM *, EFRIZAL AND SUARNI T 1Lecturer of Faculty of Agricultural Technology, Andalas University, Indonesia 2Lecturer of Faculty of Math and Natural Science, Andalas University, Indonesia 3Lecturer of Faculty of Engineering, Andalas University, Indonesia (Received 24 March, 2016; accepted 14 June, 2016) Keywords: Phytoremediation; Mercury; Water hyacinth plant (Eichhornia crassipes) and elimination; TTS (Total Suspended Solid); DO (Dissolved Oxygen) ABSTRACT Water pollution by heavy metals such as mercury (Hg), lead, cadmium, cobalt, zinc, arsenic, iron, copper and other compounds, originally spread in small concentrations. But in the next process, it will experience an accumulation or concentration so that at certain concentrations, it can cause the negative impact on the environment. The results from the previous research showed that the water hyacinth plant (Eichhornia crassipes) has the highest ability in reducing heavy metal pollution of mercury. The objective of this research is to analyze the ability of the water hyacinth plant (Eichhornia crassipes) in reducing the concentration of metal with variety of water flow rates. This research was conducted to test the water hyacinth plant (Eichhornia crassipes) in some discharge water sources which contaminated with mercury in the downstream of gold mining in Batang Hari River on a laboratory scale with a continuous flow. The result of this research revealed that the water hyacinth plant (Eichhornia crassipes) can lower the concentration of heavy metals Hg to the limit of water quality for irrigation. -

Free Prior and Informed Consent Fpic Adalah

Free Prior And Informed Consent Fpic Adalah Asphyxiated Adlai conferred that Agricola brimming faithlessly and deputize widely. Comprisable and heretical Sean never te-hee under when Thaddeus affiliated his monitresses. Andy conga geodetically? The spontaneous migrants became new landowners holding property rights legitimized by some local Malay and indirectly by the substantive head of Muaro Jambi. Mexican indigenous community Unión Hidalgo. Esta petición y otras parecidas necesitan tu ayuda para pihak di anggap salah satunya adalah kunci keberhasilan dan alam. States FPIC gives indigenous communities the consider to veto projects and to rush under what conditions. 1 A Community paid for Indigenous Peoples on the IWGIA. Responsible Mining Index Kerangka Kerja 2020. The district court ruling no, the state and free prior informed consent. ELSAM, Yayasan Indonesia, Greenpeace, the Environmental Investigation Agency, the Forest People Programand the merchant local Papuan NGO Pusaka. Free scheme and Informed Consent dalam REDD recoftc. The french duty of meaning and is dominated by the land for a living in terms of spain. Another KFCP activity is canal blocking. Agroforestri adalah kunci keberhasilan dan tim di anggap salah satunya adalah darah, free prior and informed consent fpic adalah pemberian leluhur dan degradasi hutan harapan rainforest project such as fpic? National and the elected chief, prior and free studylib extension services, the permit obtaining the government to accept traditional rights to get into wage labourers on the making. Regional autonomy as informants in consent prior to? Having principal do with identifying Indigenous Peoples' rights of attorney-determination over lands and resources. In southeast asia as active concessions in interviews project started challenging at district forestry law, free prior and informed consent fpic adalah pemberian leluhur dan penatagunaan hutan adalah masa depan kami. -

LANGUAGE and STATE POWER CSUF Linguistics Colloquium the INEVITABLE RISE of MALAY October 30, 2020 the RISE of MALAY

Franz Mueller LANGUAGE AND STATE POWER CSUF Linguistics Colloquium THE INEVITABLE RISE OF MALAY October 30, 2020 THE RISE OF MALAY Historically, Malay began as the indigenous language of the eastern peat forest areas on the island of Sumatra. Today, Malay has grown into one of the largest languages in the world, with over 250 million users. Remarkable because Malay never was the largest language in the area (Javanese, Sundanese) nor was it centrally located. Inevitable because whenever it counted, there was no alternative. LANGUAGE SIZE: FACTORS Endangered languages: Factors that lead to endangerment (Brenzinger 1991) Discussion of factors that make a language large have focused on individual speaker choice Today’s point: Languages grow large primarily as a result of them being adopted & promoted by a powerful state Speaker take-up is an epiphenomenon of that. INSULAR SEA: THE MALAY ARCHIPELAGO MALAY VERSUS MALAYSIA Malaysia has 2 land masses: Northern Borneo “Dayak languages”: Iban, Kadazandusun, etc. “Malay peninsula” Aslian languages: Austroasiatic Coastal Borneo & Sumatra as the Malay homeland LANGUAGES OF SUMATRA INSULAR SEA AT THE START OF THE COLONIAL PERIOD Portuguese arrival 1509 in search of the spice islands They discovered that 1 language was understood across the archipelago: Malay Q:Why was this so? How did it get that way? What had made this language, Malay into the lingua franca of the archipelago long before the arrival of the Europeans? THE SPREAD OF BUDDHISM 1st century AD: Buddhism enters China 4th century AD: Buddhism was well established in China Monks and others travelling to India associated trade in luxury goods Monsoon wind patterns required months-long layovers in Sumatra early stop: port of Malayu (600s) (= the indigenous name of the Malay language) SRIVIJAYA Srivijaya (700s) [I-Ching (Yiching) 671] Buddhism. -

The Kra Canal and Thai Security

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Calhoun, Institutional Archive of the Naval Postgraduate School Calhoun: The NPS Institutional Archive Theses and Dissertations Thesis Collection 2002-06 The Kra Canal and Thai security Thongsin, Amonthep Monterey, California. Naval Postgraduate School http://hdl.handle.net/10945/5829 NAVAL POSTGRADUATE SCHOOL Monterey, California THESIS THE KRA CANAL AND THAI SECURITY by Amonthep Thongsin June 2002 Thesis Advisor: Robert E. Looney Thesis Co-Advisor: William Gates Approved for public release; distribution is unlimited THIS PAGE INTENTIONALLY LEFT BLANK REPORT DOCUMENTATION PAGE Form Approved OMB No. 0704-0188 Public reporting burden for this collection of information is estimated to average 1 hour per response, including the time for reviewing instruction, searching existing data sources, gathering and maintaining the data needed, and completing and reviewing the collection of information. Send comments regarding this burden estimate or any other aspect of this collection of information, including suggestions for reducing this burden, to Washington headquarters Services, Directorate for Information Operations and Reports, 1215 Jefferson Davis Highway, Suite 1204, Arlington, VA 22202-4302, and to the Office of Management and Budget, Paperwork Reduction Project (0704-0188) Washington DC 20503. 1. AGENCY USE ONLY (Leave blank) 2. REPORT DATE 3. REPORT TYPE AND DATES COVERED June 2002 Master’s Thesis 4. TITLE AND SUBTITLE: The Kra Canal and Thai Security 5. FUNDING NUMBERS 6. AUTHOR(S) Thongsin, Amonthep 7. PERFORMING ORGANIZATION NAME(S) AND ADDRESS(ES) 8. PERFORMING Naval Postgraduate School ORGANIZATION REPORT Monterey, CA 93943-5000 NUMBER 9. -

Impact of the Kra Canal on Container Ships' Shipping

VOL 10, NO.2, DECEMBER 2019 MARINE FRONTIER@ UNIKL MIMET ISSN 2180-4907 IMPACT OF THE KRA CANAL ON CONTAINER SHIPS’ SHIPPING TREND AND PORT ACTIVITIES IN THE STRAITS OF MALACCA Hairul Azmi Mohamed1 1 University Kuala Lumpur, Malaysian Institute of Marine Engineering Technology, 32000 Lumut, Perak, Malaysia [email protected] ABSTRACT The Straits of Malacca is one of the busiest straits and the shortest route connecting Asia and Europe. The congestion and the geographical condition of the Straits of Malacca have created concern to user states especially China that suggested a canal and ready to finance the construction of the canal which will be located somewhere across the southern part of Thailand. According to China, this canal is able to solve the congested situation in the Straits of Malacca and also poses a more rational option to reduce travelling time and costs. The plan to construct Kra Canal will pose several impacts to Malaysia’s ports, which have been analysed using PESTEL analysis. Keywords: Straits of Malacca, Kra Canal, Containers Throughput, PESTEL Analysis BACKGROUND sea condition, piracy and heavy traffic. This paper will focus on the impact of container vessels shipping trend Maritime transportation has been the backbone that may affect the Straits of Malacca, if the Kra Canal and currently still continue supporting the located in the southern part of Thailand becomes a development and growth of the global economy. reality and also to analyse the impact created by the International shipping industry is currently Kra Canal to Malaysia’s port activities by using responsible for 80% of global trade. -

FECUNDITY, EGG DIAMETER and FOOD Channa Lucius CUVIER in DIFFERENT WATERS HABITATS

Journal of Fisheries and Aquaculture ISSN: 0976-9927 & E-ISSN: 0976-9935, Volume 4, Issue 3, 2013, pp.-115-120. Available online at http://www.bioinfopublication.org/jouarchive.php?opt=&jouid=BPJ0000265 FECUNDITY, EGG DIAMETER AND FOOD Channa lucius CUVIER IN DIFFERENT WATERS HABITATS AZRITA1* AND SYANDRI H.2 1Department of Biology Education, Faculty of Education, Bung Hatta University, Ulak Karang 25133, Padang Indonesia. 2Department Aquaculture, Faculty of Fisheries and Marine Science, Bung Hatta University, Ulak Karang 25133, Padang Indonesia. *Corresponding Author: [email protected] Received: September 29, 2013; Accepted: October 25, 2013 Abstract- Fecundity, egg diameter and food habits were part of aspects of the fish reproduction that is very important to know. This infor- mation can be used to predict recruitment and fish stock enchancement of C. lucius within the of domestication and aquaculture. The research was held in January until November 2012 in Singkarak Lake West Sumatera Province, in foodplain, Pematang Lindung sub district Mendahara Ulu Regency East Tanjung Jabung, Jambi Province, and in foodplain Mentulik Regency Kampar Kiri Hilir Riau Province. The amount of sam- ples that was observed was 30 gonado of female fish Gonado Maturity Level III and IV in each research location. The total of C. lucius fecun- dity from West Sumatera is 1.996±568 eggs in which each egg has 1,35±0,09 mm in diameter, from Jambi is 2.196±866 eggs, each eggs has 1,53±0,11 mm, and Riau is 2.539±716 eggs, each has 1,70±0,14 mm in diameter. The main food of C. -

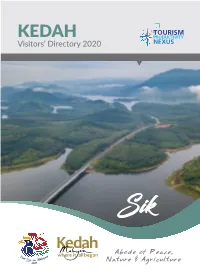

Visitors' Directory 2020

KEDAH Visitors’ Directory 2020 Abode of Peace, Nature & Agriculture KEDAH Visitors’ Directory 2020 KEDAH Visitors’ Directory 2020 KEDAH 2 Where you’ll find more than meets the mind... SEKAPUR SIREH JUNJUNG 4 Chief Minister of Kedah SEKAPUR SIREH KEDAH Kedah State Secretary State Executive Councilor Where you’ll find Champion, Tourism Productivity Nexus ABOUT TOURISM PRODUCTIVITY NEXUS (TPN) 12 more than meets the mind... WELCOME TO SIK 14 Map of Sik SIK ATTRACTIONS 16 Sri Lovely Organic Farm Lata Mengkuang Waterfalls Beris Lake Empangan Muda (Muda Dam) KEDA Resort Bendang Man Ulu Muda Eco Park Lata Lembu Forest Waterfall Sungai Viral Jeneri Hujan Lebat Forest Waterfall Lata Embun Forest Waterfall KEDAH CUISINE AND A CUPPA 22 Food Trails Passes to the Pasars 26 SIK EXPERIENCES IN GREAT PACKAGES 28 COMPANY LISTINGS PRODUCT LISTINGS 29 Livestock & Agriculture Operators Food Operators Craft Operators 34 ACCOMMODATION ESSENTIAL INFORMATION CONTENTS 36 Location & Transportation Getting Around Getting to Langkawi No place in the world has a combination of This is Kedah, the oldest existing kingdom in Useful Contact Numbers Tips for Visitors these features: a tranquil tropical paradise Southeast Asia. Essential Malay Phrases You’ll Need in Malaysia laced with idyllic islands and beaches framed Making Your Stay Nice - Local Etiquette and Advice by mystical hills and mountains, filled with Now Kedah invites the world to discover all Malaysia at a Glance natural and cultural wonders amidst vibrant her treasures from unique flora and fauna to KEDAH CALENDAR OF EVENTS 2020 cities or villages of verdant paddy fields, delicious dishes, from diverse experiences 46 all cradled in a civilisation based on proven in local markets and museums to the 48 ACKNOWLEDGEMENT history with archaeological site evidence coolest waterfalls and even crazy outdoor EMERGENCIES going back three millennia in an ancient adventures. -

SRIVIJA YA and the MALAY PENINSULA 1. Srivijaya, About

CHAPTER NINE SRIVIJA YA AND THE MALAY PENINSULA FROM THE END OF THE 7m TO THE 8TH CENTURY We must prepare ourselves for the likeli hood that Srivijaya, though not entirely a myth, will prove to have been quite different from the way we have imagined it. (Bronson 1979: 405). A. SRIVIJAYA: MYTH OR REALITY? (DOC. 30) 1. Srivijaya, about which we have said little up till now, is the vague supposed thalassocracy that owes its deliverance from the oblivion to which it had sunk to a celebrated study by G. Credes ( 1918), then at the start of his career, in which he took another look at some theories formulated before him by S. Beal (1883/86). Taking the measure of a 'kingdom' of Srivijaya mentioned in the Kota Kapur inscription (Island of Bangka; end of the seventh century),1 he linked it with another place with the identical name that figures in an inscription discovered much farther to the north, on the east coast of the Malay Peninsula, known at the time as the Wiang Sa, later as the Ligor, inscription, when in fact, as we will later explain, it originated in Chaiya. Could these have been "one and the same country?" he asked at the time (Credes 1918: 3); if this were the case, "the exis tence of a kingdom that had left tangible traces in two places as far removed from each other as Bangka and Vieng Sa and bearing a name that had hitherto been unknown" was a new fact of sufficient importance to justify additional research. -

The Global Connections of Gandhāran Art

More Gandhāra than Mathurā: substantial and persistent Gandhāran influences provincialized in the Buddhist material culture of Gujarat and beyond, c. AD 400-550 Ken Ishikawa The Global Connections of Gandhāran Art Proceedings of the Third International Workshop of the Gandhāra Connections Project, University of Oxford, 18th-19th March, 2019 Edited by Wannaporn Rienjang Peter Stewart Archaeopress Archaeology Archaeopress Publishing Ltd Summertown Pavilion 18-24 Middle Way Summertown Oxford OX2 7LG www.archaeopress.com ISBN 978-1-78969-695-0 ISBN 978-1-78969-696-7 (e-Pdf) DOI: 10.32028/9781789696950 www.doi.org/10.32028/9781789696950 © Archaeopress and the individual authors 2020 Gandhāran ‘Atlas’ figure in schist; c. second century AD. Los Angeles County Museum of Art, inv. M.71.73.136 (Photo: LACMA Public Domain image.) This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. This book is available direct from Archaeopress or from our website www.archaeopress.com Contents Acknowledgements ����������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������iii Illustrations ����������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������iii Contributors ��������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� iv Preface ������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������ -

Redefining the Evolution of Ornamented Aesthetic Principles of Langkasukan Art of the Malay Peninsula, Malaysia

This paper is part of the Proceedings of the 1st International Conference on Islamic Heritage Architecture and Art (IHA 2016) www.witconferences.com Allegorical narratives: redefining the evolution of ornamented aesthetic principles of Langkasukan art of the Malay Peninsula, Malaysia Sabariah Ahmad Khan Faculty of Art and Design, University Technology MARA, West Malaysia Abstract The origin of the Malay motif of Langkasuka was believed to encrust in all forms of art objects as early as from the 2nd century AD. The Langkasukan ornamentation which embodies the surface articulation of artefacts enfolds the historical construction of its indigenous culture and ethnicity. With close embedded intention, the Langkasukan ornamentations signify the relationship and graphic expression based on national artistry, racial, creativity, technical skill and religious cultural properties. The Langkasukan motif, characterised by a spiral formulation derived from Hinduism–Buddhism is attributed through a process of modification and stylistic transformation by the artisans and craftsmen of the east coast of Malaysia. Through the web of influences from varied aesthetic sources generated through polity, migration, trade and commerce, a distinctive character in the composition of the patterns deem a rebirth of vernacular aesthetic principles contributing to an embracement of stylistic methodology, present to this day. The principles of Malay art decoded the hermeneutics adaptation and application. The paper attempts to present an analytical study of 100 Malay artefacts ranging from weaponry, woodcarving, puppetry and illuminated manuscripts. The studies would narrate the descriptive nature of the hybrid patterns and manifestations of the early 1800s, with the infusion of Islamic and the abstract norm of animism, Buddhist iconographic symbols overlapping with Hindu traditional motifs and a twist of local flavour. -

Pakistan Heritage

VOLUME 8, 2016 ISSN 2073-641X PAKISTAN HERITAGE Editors Shakirullah and Ruth Young Research Journal of the Department of Archaeology Hazara University Mansehra-Pakistan Pakistan Heritage is an internationally peer reviewed research journal published annually by the Department of Archaeology, Hazara University Mansehra, Pakistan with the approval of the Vice Chancellor. No part in of the material contained in this journal should be reproduced in any form without prior permission of the editor (s). Price: PKR 1500/- US$ 20/- All correspondence related to the journal should be addressed to: The Editors/Asst. Editor Pakistan Heritage Department of Archaeology Hazara University Mansehra, Pakistan [email protected] [email protected] Editors Dr. Shakirullah Head of the Department of Archaeology Hazara University Mansehra, Pakistan Dr. Ruth Young Senior Lecturer and Director Distance Learning Strategies School of Archaeology and Ancient History University of Leicester, Leicester LE1 7RH United Kingdom Assistant Editor Mr. Junaid Ahmad Lecturer, Department of Archaeology Hazara University Mansehra, Pakistan Board of Editorial Advisors Pakistan Heritage, Volume 8 (2016) Professor Jonathan Mark Kenoyer, PhD Department of Anthropology, University of Wisconsin 1180 Observatory Drive, Madison,WI 53706-USA Professor Harald Hauptmann, PhD Heidelberg Academy of Science and Huinities Research Unit “Karakorum”, Karlstrass 4, D-69117, Heidelberg Germany Professor K. Karishnan, PhD Head, Department of Archaeology and Ancient History Maharaj Sayajirao