Factors Influencing Burrow Dimensions of Ground Squirrels

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Utah Prairie Dogs Range from 12 – 16 Inches Dog

National Park Service Bryce Canyon U.S. Department of the Interior Bryce Canyon National Park Utah Prairie Dog (Cynomys parvidens) All photos by Kevin Doxstater Prairie Dogs are ground-dwelling members of the squirrel family found only in North America. There are five species within the genus and the Utah Prairie Dog is the smallest member of the group. Restricted to the southwestern corner of Utah, they are a threatened species that has suffered population declines due to habitat loss and other factors. Vital Statistics Utah Prairie Dogs range from 12 – 16 inches Dog . Utah Prairie Dogs reach maturity in (30.5 – 40.6 cm) in length and weigh from 1 year; females have a life span of about 1 – 3 pounds (.45 – 1.4 kg). Color ranges 8 years, males live approximately 5 years. from cinnamon to clay and they have a fairly Interestingly, they are the only non- distinct black eyebrow (or stripe) not seen fish vertebrate species endemic (found in any of the other 4 prairie dog species. nowhere else in the world) to the State of Their short tail is white tipped like that of Utah. their close relative the White-tailed Prairie Habitat and Diet Like the other members of the genus, for the remaining time. These include Utah Prairie Dogs live in colonies or serving as a sentry looking for intruders or “towns” in meadows with short grasses. predators, play, mutual grooming, defense Individual colonies will be further divided of territory or young, or burrow and nest into territories occupied by social groups construction. -

Delimiting Species in the Genus Otospermophilus (Rodentia: Sciuridae), Using Genetics, Ecology, and Morphology

bs_bs_banner Biological Journal of the Linnean Society, 2014, 113, 1136–1151. With 5 figures Delimiting species in the genus Otospermophilus (Rodentia: Sciuridae), using genetics, ecology, and morphology MARK A. PHUONG1*, MARISA C. W. LIM1, DANIEL R. WAIT1, KEVIN C. ROWE1,2 and CRAIG MORITZ1,3 1Department of Integrative Biology and Museum of Vertebrate Zoology, University of California, Berkeley, 3101 Valley Life Science Building, Berkeley, CA 94720, USA 2Sciences Department, Museum Victoria, Melbourne, VIC 3001, Australia 3Research School of Biology, The Australian National University, Acton, ACT 0200, Australia Received 16 April 2014; revised 6 July 2014; accepted for publication 7 July 2014 We apply an integrative taxonomy approach to delimit species of ground squirrels in the genus Otospermophilus because the diverse evolutionary histories of organisms shape the existence of taxonomic characters. Previous studies of mitochondrial DNA from this group recovered three divergent lineages within Otospermophilus beecheyi separated into northern, central, and southern geographical populations, with Otospermophilus atricapillus nested within the southern lineage of O. beecheyi. To further evaluate species boundaries within this complex, we collected additional genetic data (one mitochondrial locus, 11 microsatellite markers, and 11 nuclear loci), environmental data (eight bioclimatic variables), and morphological data (23 skull measurements). We used the maximum number of possible taxa (O. atricapillus, Northern O. beecheyi, Central O. beecheyi, and Southern O. beecheyi) as our operational taxonomic units (OTUs) and examined patterns of divergence between these OTUs. Phenotypic measures (both environmental and morphological) showed little differentiation among OTUs. By contrast, all genetic datasets supported the evolutionary independence of Northern O. beecheyi, although they were less consistent in their support for other OTUs as distinct species. -

Program & Faculty Guide

Program & Faculty Guide UNLV School of Life Sciences UNIVERSITY OF NEVADA, LAS VEGAS Contents From the Director ..................... 3 About UNLV .............................. 4 Programs .................................. 5 Facilities ................................... 7 Graduate Students ..................11 Postdoctoral Scholars ............13 Faculty Researchers .............. 15 UNLV School of Life Sciences From the Director The School of Life Sciences (SoLS) is one of the largest academic units on the University of Nevada, Las Vegas (UNLV) campus. It has 30 full-time faculty members, 10 adjunct and research faculty, more than 1,900 undergraduate majors, and approximately 55 graduate students. The school’s offices and laborato- ries are located in four buildings: Juanita Greer White Hall (WHI), the Science and Engineering Building (SEB), the White Hall Annex (WHA2), the Campus Lab Building (CLB). Research facilities on campus include centers for bioinformatics/biostatics with access to supercomputer facilities, confocal and biological imaging core with a new a high-speed laser-scanning microscope, genomics center, greenhouses, tissue culture facilities, environmental chambers and mod- ern animal care facilities. The faculty research and graduate programs are or- ganized into Bioinformatics, Cell & Molecular Biology, Ecology & Evolutionary Biology, Integrative Physiology, School of Life Sciences Director Frank van Breukelen and Microbiology. SoLS faculty are recruited from some of the best research institutions and currently collaborate with the Nevada Institute of Personalized Medicine (NIPM), Lou Ruvo Center, Desert Research Institute (DRI), BLM, USGS, US National Park Service, and with faculty and researchers at many universities and government agencies throughout the nation and international institutions, providing ex- panded opportunities for our students. The faculty compete successfully for funding from BLM, DOE, DOI, FWS, NASA, NIH, NSF, USDA, USGS and other agencies. -

Special Publications Museum of Texas Tech University Number 63 18 September 2014

Special Publications Museum of Texas Tech University Number 63 18 September 2014 List of Recent Land Mammals of Mexico, 2014 José Ramírez-Pulido, Noé González-Ruiz, Alfred L. Gardner, and Joaquín Arroyo-Cabrales.0 Front cover: Image of the cover of Nova Plantarvm, Animalivm et Mineralivm Mexicanorvm Historia, by Francisci Hernández et al. (1651), which included the first list of the mammals found in Mexico. Cover image courtesy of the John Carter Brown Library at Brown University. SPECIAL PUBLICATIONS Museum of Texas Tech University Number 63 List of Recent Land Mammals of Mexico, 2014 JOSÉ RAMÍREZ-PULIDO, NOÉ GONZÁLEZ-RUIZ, ALFRED L. GARDNER, AND JOAQUÍN ARROYO-CABRALES Layout and Design: Lisa Bradley Cover Design: Image courtesy of the John Carter Brown Library at Brown University Production Editor: Lisa Bradley Copyright 2014, Museum of Texas Tech University This publication is available free of charge in PDF format from the website of the Natural Sciences Research Laboratory, Museum of Texas Tech University (nsrl.ttu.edu). The authors and the Museum of Texas Tech University hereby grant permission to interested parties to download or print this publication for personal or educational (not for profit) use. Re-publication of any part of this paper in other works is not permitted without prior written permission of the Museum of Texas Tech University. This book was set in Times New Roman and printed on acid-free paper that meets the guidelines for per- manence and durability of the Committee on Production Guidelines for Book Longevity of the Council on Library Resources. Printed: 18 September 2014 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Special Publications of the Museum of Texas Tech University, Number 63 Series Editor: Robert J. -

Status Review Finding for the Black-Tailed Prairie Dog

QUESTIONS AND ANSWERS REGARDING THE STATUS REVIEW FINDING FOR THE BLACK-TAILED PRAIRIE DOG What are the findings of the black-tailed prairie dog status review? The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service has completed a status review of the black-tailed prairie dog and has determined it does not warrant protection as a threatened or endangered species under the Endangered Species Act. The Service bases its conclusion for this finding after a thorough review of all the available scientific and commercial information regarding the status of the black-tailed prairie dog and the potential impacts to the species. What is a status review? A status review, also known as a 12-month finding, makes public the Service=s decision on a petition to list a species as threatened or endangered under the Endangered Species Act. The finding is based on a thorough assessment of the available information on the species, as detailed in the species= status review. One of three possible conclusions can be reached as part of the finding: that listing is warranted, not warranted, or warranted but presently precluded by other higher-priority listing activities involving other species. In the case of black-tailed prairie dog, the Service found that the black-tailed prairie dog is not likely to become a threatened or endangered species within the foreseeable future in all or a significant portion of its range. Therefore, listing of the black-tailed prairie dog as a threatened or endangered species under the Endangered Species Act is not warranted at this time. What specifically does the Service look at to determine if a species needs to be listed as threatened or endangered? We consider the factors specified in the Endangered Species Act to determine whether a species meets the definition of “threatened” or “endangered” per the criteria stated in the Act. -

45762554013.Pdf

Mastozoología Neotropical ISSN: 0327-9383 ISSN: 1666-0536 [email protected] Sociedad Argentina para el Estudio de los Mamíferos Argentina Flores-Alta, Daniel; Rivera-Ortíz, Francisco A.; Contreras-González, Ana M. RECORD OF A POPULATION AND DESCRIPTION OF SOME ASPECTS OF THE LIFE HISTORY OF Notocitellus adocetus IN THE NORTH OF THE STATE OF GUERRERO, MEXICO Mastozoología Neotropical, vol. 26, no. 1, 2019, -June, pp. 175-181 Sociedad Argentina para el Estudio de los Mamíferos Argentina Available in: https://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=45762554013 How to cite Complete issue Scientific Information System Redalyc More information about this article Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America and the Caribbean, Spain and Journal's webpage in redalyc.org Portugal Project academic non-profit, developed under the open access initiative Mastozoología Neotropical, 26(1):175-181, Mendoza, 2019 Copyright ©SAREM, 2019 Versión on-line ISSN 1666-0536 http://www.sarem.org.ar https://doi.org/10.31687/saremMN.19.26.1.0.02 http://www.sbmz.com.br Nota RECORD OF A POPULATION AND DESCRIPTION OF SOME ASPECTS OF THE LIFE HISTORY OF Notocitellus adocetus IN THE NORTH OF THE STATE OF GUERRERO, MEXICO Daniel Flores-Alta, Francisco A. Rivera-Ortíz and Ana M. Contreras-González Unidad de Biotecnología y Prototipos, Laboratorio de Ecología, Facultad de Estudios Superiores Iztacala, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, Los Reyes Iztacala. Tlalnepantla, Estado de México, México [correspondencia: Ana M. Contreras-González <[email protected]>]. ABSTRACT. The rodent Notocitellus adocetus is endemic to Mexico, and little is known about its life history. We describe a population of N. -

Mammal Species Native to the USA and Canada for Which the MIL Has an Image (296) 31 July 2021

Mammal species native to the USA and Canada for which the MIL has an image (296) 31 July 2021 ARTIODACTYLA (includes CETACEA) (38) ANTILOCAPRIDAE - pronghorns Antilocapra americana - Pronghorn BALAENIDAE - bowheads and right whales 1. Balaena mysticetus – Bowhead Whale BALAENOPTERIDAE -rorqual whales 1. Balaenoptera acutorostrata – Common Minke Whale 2. Balaenoptera borealis - Sei Whale 3. Balaenoptera brydei - Bryde’s Whale 4. Balaenoptera musculus - Blue Whale 5. Balaenoptera physalus - Fin Whale 6. Eschrichtius robustus - Gray Whale 7. Megaptera novaeangliae - Humpback Whale BOVIDAE - cattle, sheep, goats, and antelopes 1. Bos bison - American Bison 2. Oreamnos americanus - Mountain Goat 3. Ovibos moschatus - Muskox 4. Ovis canadensis - Bighorn Sheep 5. Ovis dalli - Thinhorn Sheep CERVIDAE - deer 1. Alces alces - Moose 2. Cervus canadensis - Wapiti (Elk) 3. Odocoileus hemionus - Mule Deer 4. Odocoileus virginianus - White-tailed Deer 5. Rangifer tarandus -Caribou DELPHINIDAE - ocean dolphins 1. Delphinus delphis - Common Dolphin 2. Globicephala macrorhynchus - Short-finned Pilot Whale 3. Grampus griseus - Risso's Dolphin 4. Lagenorhynchus albirostris - White-beaked Dolphin 5. Lissodelphis borealis - Northern Right-whale Dolphin 6. Orcinus orca - Killer Whale 7. Peponocephala electra - Melon-headed Whale 8. Pseudorca crassidens - False Killer Whale 9. Sagmatias obliquidens - Pacific White-sided Dolphin 10. Stenella coeruleoalba - Striped Dolphin 11. Stenella frontalis – Atlantic Spotted Dolphin 12. Steno bredanensis - Rough-toothed Dolphin 13. Tursiops truncatus - Common Bottlenose Dolphin MONODONTIDAE - narwhals, belugas 1. Delphinapterus leucas - Beluga 2. Monodon monoceros - Narwhal PHOCOENIDAE - porpoises 1. Phocoena phocoena - Harbor Porpoise 2. Phocoenoides dalli - Dall’s Porpoise PHYSETERIDAE - sperm whales Physeter macrocephalus – Sperm Whale TAYASSUIDAE - peccaries Dicotyles tajacu - Collared Peccary CARNIVORA (48) CANIDAE - dogs 1. Canis latrans - Coyote 2. -

Time Budgets of Wyoming Ground Squirrels, Spermophilus Elegans

Great Basin Naturalist Volume 41 Number 2 Article 9 6-30-1981 Time budgets of Wyoming ground squirrels, Spermophilus elegans David A. Zegers University of Colorado, Boulder Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/gbn Recommended Citation Zegers, David A. (1981) "Time budgets of Wyoming ground squirrels, Spermophilus elegans," Great Basin Naturalist: Vol. 41 : No. 2 , Article 9. Available at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/gbn/vol41/iss2/9 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Western North American Naturalist Publications at BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Great Basin Naturalist by an authorized editor of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. TIME BUDGETS OF WYOMING GROUND SQUIRRELS, SPERMOPHILUS ELEGANS David A. Zegers' .\bstract.— Time budget of free-living adult Spermophiltts elegans differed significantly from that of juveniles in the Front Range of the Rockies during 1974-1975. No differences were found between males and females. Hour of day. day since emergence, air temperature, cloud cover, and presence of predators all correlated with the frequency of various components of the time budget. Study of time budgets is important in com- binocular, and a 20X telescope to observe the prehending the roles of animals in ecosystems squirrels from a blind. The animals were as well as understanding their basic patterns marked for individual recognition from a dis- of behavior. Time budgets constructed for a tance using a unique combination of freeze few ground .squirrels [the Columbian ground brands (Hadow 1972) located at one or two squirrel, Spemiophihis columbianus (Betts of the spots on the animal's body. -

BYE, BYE BIRDIE Introduction

BYE, BYE BIRDIE introduction Humankind is now precipitating the extinction of large numbers Studies For Our Global Future of animals, birds, insects, and plants. Despite human activity, extinction occurs at a natural rate of about one to three species per year. Current estimates suggest that we are losing species at 1,000 to 10,000 times the natural rate. This means that concept dozens of species could be going extinct every day. Between The rate of wildlife endangerment is human impact on the natural world and issues brought on by an increasing and difficult decisions are required increasingly warm climate, over 500 known species could face to determine how to prioritize efforts to save 1 extinction by 2040. endangered species. objectives Scientists believe that many of the species being lost carry untold potential benefits for the health and economic stability Students will be able to: of the planet. With limited funding available for conservation, • Develop and apply a list of criteria that can many believe that humanity should make some tough choices be used to make decisions about protecting and decide which species can and should be saved. endangered species. • Conduct research on an endangered species Vocabulary: biodiversity, ecosystems, ecosystem services, and effectively communicate to classmates endangered species, extinction, indicator species, IUCN Red List its importance and why it should be saved. of Threatened Species, keystone species, poaching, umbrella subjects species Environmental Science (General and AP), Biology, English Language Arts materials skills Critical thinking, researching, comparing and • Research Guide (provided) evaluating, public speaking, decision making method Students determine a list of criteria to use procedure when deciding the fate of endangered species, then conduct research on a specific species 1. -

Journal of the Helminthological Society of Washington 63(2) 1996

July 1996 Number 2 Of of Washington A semiannual journal of research devoted to Helminthology and all branches of Parasitology Supported in part by the Brayton H. Ransom Memorial Trust Fund D. C. KRITSKY, W. A. :B6EC3ER, AND M, JEGU. NedtropicaliMonogehoidea/lS. An- — cyrocephalinae (Dactylogyridae) of Piranha and Their Relatives (Teleostei, JSer- rasalmidae) from Brazil and French Guiana: Species of Notozothecium Boeger and Kritsky, 1988, and Mymarotheciumgem. n. ..__ _______ __, ________ ..x,- ______ .s.... A. KOHN, C. P. SANTOS, AND-B. LEBEDEV. Metacdmpiella euzeti gen. n., sp, n., and I -Hargicola oligoplites~(Hargis, 1951) (Monogenea: Allodiscpcotylidae) from Bra- " zilian Fishes . ___________ ,:...L".. _______ j __ L'. _______l _; ________ 1 ________ _ __________ ______ _ .' _____ . __.. 176 C. P. SANTO?, T. SOUTO-PADRGN, AND R. M. LANFREDI. Atriasterheterodus (Levedev and Paruchin, 1969) and Polylabris tubicimts (Papema and Kohn, 1964) (Mono- ' genea) from Diplodus argenteus (Val., 1830) (Teleostei: Sparidae) from Brazil 181 . I...N- CAIRA AND T. BARDOS. Further Information on :.Gymnorhynchus isuri (Trypa- i/:norhyncha: Gymnorhynchidae) from the Shortfin Make Shark ...,.'. ..^_.-"_~ ____. ; 188 O. M. AMIN AND W. L.'MmcKLEY. Parasites of Some Fisji Introduced into an Arizona Reservoir, with Notes on Introductions — . ____ : ______ . ___.i;__ L____ _ . ______ :___ _ .193 O. M. AMIN AND O. SEY. Acanthocephala from Arabian Gulf Fishes off Kuwait, with 'Descriptions of Neoechinorhynchus dimorphospinus sp. n. XNeoechinorhyrichi- dae), Tegorhyrichus holospinosus sp. n. (l\lio&&ntid&e),:Micracanthorynchina-ku- waitensis sp. n. (Rhadinorhynchidae), and Sleriidrorhynchus breviclavipraboscis gen. n., sp. p. (Diplosentidae); and Key to Species of the Genus Micracanthor- . -

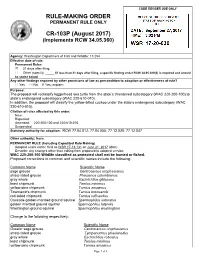

Filed As WSR 17-20-030 on September 27, 2017

CODE REVISER USE ONLY RULE-MAKING ORDER PERMANENT RULE ONLY CR-103P (August 2017) (Implements RCW 34.05.360) Agency: Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife: 17-254 Effective date of rule: Permanent Rules ☒ 31 days after filing. ☐ Other (specify) (If less than 31 days after filing, a specific finding under RCW 34.05.380(3) is required and should be stated below) Any other findings required by other provisions of law as precondition to adoption or effectiveness of rule? ☐ Yes ☒ No If Yes, explain: Purpose: The proposal will reclassify loggerhead sea turtle from the state’s threatened subcategory (WAC 220-200-100) to state’s endangered subcategory (WAC 220-610-010). In addition, the proposal will classify the yellow-billed cuckoo under the state’s endangered subcategory (WAC 220-610-010). Citation of rules affected by this order: New: Repealed: Amended: 220-200-100 and 220-610-010. Suspended: Statutory authority for adoption: RCW 77.04.012; 77.04.055; 77.12.020; 77.12.047 Other authority: None. PERMANENT RULE (Including Expedited Rule Making) Adopted under notice filed as WSR 17-13-131 on June 21, 2017 (date). Describe any changes other than editing from proposed to adopted version: WAC 220-200-100 Wildlife classified as protected shall not be hunted or fished. Proposed corrections to common and scientific names include the following: Common Name Scientific Name sage grouse Centrocercus urophasianus sharp-tailed grouse Phasianus columbianus gray whale Eschrichtius gibbosus least chipmunk Tamius minimus yellow-pine chipmunk Tamius amoenus -

Introduction to Risk Assessments for Methods Used in Wildlife Damage Management

Human Health and Ecological Risk Assessment for the Use of Wildlife Damage Management Methods by USDA-APHIS-Wildlife Services Chapter I Introduction to Risk Assessments for Methods Used in Wildlife Damage Management MAY 2017 Introduction to Risk Assessments for Methods Used in Wildlife Damage Management EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The USDA-APHIS-Wildlife Services (WS) Program completed Risk Assessments for methods used in wildlife damage management in 1992 (USDA 1997). While those Risk Assessments are still valid, for the most part, the WS Program has expanded programs into different areas of wildlife management and wildlife damage management (WDM) such as work on airports, with feral swine and management of other invasive species, disease surveillance and control. Inherently, these programs have expanded the methods being used. Additionally, research has improved the effectiveness and selectiveness of methods being used and made new tools available. Thus, new methods and strategies will be analyzed in these risk assessments to cover the latest methods being used. The risk assements are being completed in Chapters and will be made available on a website, which can be regularly updated. Similar methods are combined into single risk assessments for efficiency; for example Chapter IV contains all foothold traps being used including standard foothold traps, pole traps, and foot cuffs. The Introduction to Risk Assessments is Chapter I and was completed to give an overall summary of the national WS Program. The methods being used and risks to target and nontarget species, people, pets, and the environment, and the issue of humanenss are discussed in this Chapter. From FY11 to FY15, WS had work tasks associated with 53 different methods being used.