You're Out! Explaining Non-Criminal Diplomatic Expulsion

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Of Diplomatic Immunity in the United States: a Claims Fund Proposal

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by Fordham University School of Law Fordham International Law Journal Volume 4, Issue 1 1980 Article 6 Compensation for “Victims” of Diplomatic Immunity in the United States: A Claims Fund Proposal R. Scott Garley∗ ∗ Copyright c 1980 by the authors. Fordham International Law Journal is produced by The Berke- ley Electronic Press (bepress). http://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/ilj Compensation for “Victims” of Diplomatic Immunity in the United States: A Claims Fund Proposal R. Scott Garley Abstract This Note will briefly trace the development of diplomatic immunity law in the United States, including the changes adopted by the Vienna Convention, leading to the passage of the DRA in 1978. The discussion will then focus upon the DRA and point out a few of the areas in which the statute may fail to provide adequate protection for the rights of private citizens in the United States. As a means of curing the inadequacies of the present DRA, the feasibility of a claims fund designed to compensate the victims of the tortious and criminal acts of foreign diplomats in the United States will be examined. COMPENSATION FOR "VICTIMS" OF DIPLOMATIC IMMUNITY IN THE UNITED STATES: A CLAIMS FUND PROPOSAL INTRODUCTION In 1978, Congress passed the Diplomatic Relations Act (DRA)1 which codified the 1961 Vienna Convention on Diplomatic Rela- tions. 2 The DRA repealed 22 U.S.C. §§ 252-254, the prior United States statute on the subject,3 and established the Vienna Conven- tion as the sole standard to be applied in cases involving the immu- nity of diplomatic personnel4 in the United States. -

Legal Regime of Persona Non Grata and the Namru-2 Case

Journal of Law, Policy and Globalization www.iiste.org ISSN 2224-3240 (Paper) ISSN 2224-3259 (Online) Vol.32, 2014 Legal Regime of Persona Non Grata and the Namru-2 Case Marcel Hendrapati* Law Faculty, Hasanuddin University, Jalan Perintis Kemerdekaan, Kampus Unhas Tamalanrea KM.10, Makassar-90245, Republic of Indonesia * E-mail of the corresponding author: [email protected] Abstract Just like the diplomatic immunity principle, the principle of persona non grata aims to ensure justice for both the state seeking to evict a diplomat (receiving state) and the state whose diplomat is being evicted (sending state). This is because both principles can guarantee the dignity and equality of sovereign states when resolving issues in international relation. Not every statement of persona non grata has to culminate in expulsion because a statement may be issued by the receiving state both after the diplomatic agent has started performing his functions and even before he arrives at the receiving state. If such a statement is followed by the expulsion of the diplomat, it should be based on article 41 of the Vienna Convention, 1961 (infringement on laws of receiving state and/or espionage actions). Also, expulsion may occur due to war and severance of diplomatic relation between two states. Indonesia has had to deal with issues of persona non grata on several occasions both as receiving and sending state. This paper analyses several cases of declaration of persona non grata involving several countries, especially Indonesia in order to give a better understanding of how the declaration of persona non grata plays out between states, and the significance of the Vienna Convention of 1961 on diplomatic relations. -

Preventive Diplomacy: Regions in Focus

Preventive Diplomacy: Regions in Focus DECEMBER 2011 INTERNATIONAL PEACE INSTITUTE Cover Photo: UN Secretary-General ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Ban Ki-moon (left) is received by Guillaume Soro, Prime Minister of IPI owes a debt of thanks to its many donors, whose Côte d'Ivoire, at Yamoussoukro support makes publications like this one possible. In partic - airport. May 21, 2011. © UN ular, IPI would like to thank the governments of Finland, Photo/Basile Zoma. Norway, and Sweden for their generous contributions to The views expressed in this paper IPI's Coping with Crisis Program. Also, IPI would like to represent those of the authors and thank the Mediation Support Unit of the UN Department of not necessarily those of IPI. IPI Political Affairs for giving it the opportunity to contribute welcomes consideration of a wide range of perspectives in the pursuit to the process that led up to the Secretary-General's report of a well-informed debate on critical on preventive diplomacy. policies and issues in international affairs. IPI Publications Adam Lupel, Editor and Senior Fellow Marie O’Reilly, Publications Officer Suggested Citation: Francesco Mancini, ed., “Preventive Diplomacy: Regions in Focus,” New York: International Peace Institute, December 2011. © by International Peace Institute, 2011 All Rights Reserved www.ipinst.org CONTENTS Introduction . 1 Francesco Mancini Preventive Diplomacy in Africa: Adapting to New Realities . 4 Fabienne Hara Optimizing Preventive-Diplomacy Tools: A Latin American Perspective . 15 Sandra Borda Preventive Diplomacy in Southeast Asia: Redefining the ASEAN Way . 28 Jim Della-Giacoma Preventive Diplomacy on the Korean Peninsula: What Role for the United Nations? . 35 Leon V. -

David Hare Plays 1: Slag; Teeth N Smiles; Knuckle; Licking Hitler; Plenty Pdf

FREE DAVID HARE PLAYS 1: SLAG; TEETH N SMILES; KNUCKLE; LICKING HITLER; PLENTY PDF David Hare | 496 pages | 01 Apr 1996 | FABER & FABER | 9780571177417 | English | London, United Kingdom David Hare Plays 1 | Faber & Faber Plenty is a play by David Harefirst performed inabout British post-war disillusion. The inspiration for Plenty came from the fact that 75 per cent of the women engaged in wartime SOE operations divorced in the immediate post-war years; the title is derived from the idea that the post-war era would be a time of "plenty", which proved untrue for most of England. The play premiered Off-Broadway on 21 Octoberat the Public Theaterwhere it ran for 45 performances. Plenty was revived at Chichester inin the Festival Theatre between June. Susan Traherne, a former secret agent, is a woman conflicted by the contrast between her past, exciting triumphs and her present, more ordinary David Hare Plays 1: Slag; Teeth n Smiles; Knuckle; Licking Hitler; Plenty. However, she regrets the mundane nature of her present life, as the increasingly depressed wife of a diplomat whose career she has destroyed. Susan Traherne's story is told in a non-linear chronologyalternating between her wartime and post-wartime lives, illustrating how youthful dreams rarely are realised and how a person's personal life can affect the outside world. Sources: Playbill; [3] Lortel [2]. From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia. Official London Theatre Guide. Archived from the original on 18 January Retrieved 4 December BBC News. Archived from the original on 27 February Retrieved 5 May CS1 maint: archived copy as title link sheffieldtheatres. -

Mexico's 2006 Elections

Mexico’s 2006 Elections -name redacted- October 3, 2006 Congressional Research Service 7-.... www.crs.gov RS22462 CRS Report for Congress Prepared for Members and Committees of Congress Mexico’s 2006 Elections Summary Mexico held national elections for a new president and congress on July 2, 2006. Conservative Felipe Calderón of the National Action Party (PAN) narrowly defeated Andrés Manuel López Obrador of the leftist Party of the Democratic Revolution (PRD) in a highly contested election. Final results of the presidential election were only announced after all legal challenges had been settled. On September 5, 2006, the Elections Tribunal found that although business groups illegally interfered in the election, the effect of the interference was insufficient to warrant an annulment of the vote, and the tribunal declared PAN-candidate Felipe Calderón president-elect. PRD candidate López Obrador, who rejected the Tribunal’s decision, was named the “legitimate president” of Mexico by a National Democratic Convention on September 16. The electoral campaign touched on issues of interest to the United States including migration, border security, drug trafficking, energy policy, and the future of Mexican relations with Venezuela and Cuba. This report will not be updated. See also CRS Report RL32724, Mexico-U.S. Relations: Issues for Congress, by (name redacted) and (name redacted); CRS Report RL32735,Mexico-United States Dialogue on Migration and Border Issues, 2001-2006, by (name redacted); and CRS Report RL32934, U.S.-Mexico Economic Relations: -

Democracy, Judicialisation and the Emergence of the Supreme Court As a Policy-Maker in Mexico

The London School of Economics and Political Science Democracy, judicialisation and the emergence of the Supreme Court as a policy-maker in Mexico Camilo Emiliano Saavedra-Herrera A thesis submitted to the Department of Government of the London School of Economics for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, London, August 2013 1 Declaration I certify that the thesis I have presented for examination for the MPhil/PhD degree of the London School of Economics and Political Science is solely my own work other than where I have clearly indicated that it is the work of others (in which case the extent of any work carried out jointly by myself and any other person is clearly identified). The copyright of this thesis rests with the author. Quotation from it is permitted, provided that full acknowledgement is made. This thesis may not be reproduced without my prior written consent. I warrant that this authorisation does not, to the best of my belief, infringe the rights of any third party. I declare that my thesis consists of 73,214 words. 2 Abstract In 1994, four days after taking office, Ernesto Zedillo, the last president to govern Mexico emerging from the once hegemonic National Revolutionary Party, promoted a major redesign of the Supreme Court of Justice that substantially expanded its constitutional review powers and reduced its size from 26 to 11 members. The operation of this more compact and powerful body was left in charge of 11 justices nominated by Zedillo. During the period 1917-1994, the Supreme Court adjudicated only 63 constitutional cases of its exclusive jurisdiction. -

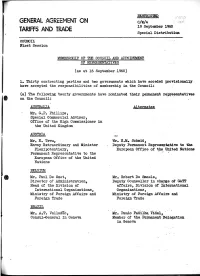

General Agreement on Tariffs And

RESTRICTED GENERAL AGREEMENT ON c/wA TARIFFS AND TRADE 19 September 1960 Special Distribution COUNCIL First Session MEMBERSHIP OF THE COUNCIL AND APPOINTMENT OF REPRESENTATIVES (as at 16 September 1960} 1. Thirty contracting parties and two governments which have acceded provisionally have accepted the responsibilities of membership in the Council: (a) The following twenty governments have nominated their permanent representatives on the Council: AUSTRALIA Alternates Mr. G.P. Phillips, Special Commercial Adviser, Office of the High Commissioner in the United Kingdom AUSTRIA ac Mr, E. Treu, Mr. E.M. Schmid. Envoy Extraordinary and Minister Deputy Permanent Representative to the Plenipotentiary, European Office of the United Nations Permanent Representative to the European Office of the United Nations BELGIUM Mr. Paul De Smet, Mr. Robert De Smaele, Director of Administration, Deputy Counsellor in charge of GATT Head of the Division of affairs, Division of International International Organizations, Organizations, Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Foreign Trade Foreign *rade BRAZIL Mr, A.T. Valladao, Mr. Paulo Padilha Vidal, ' Consul-General in Geneva Member of the Permanent Delegation in Geneva C/W/4 Page 2 Alternates CANADA Mr. J.H» Warren, Assistant Deputy Minister, Department of Trade and Commerce CHILE H.E. Mr. F. Garcia Oldini, Ambassador Extraordinary and Plenipotentiary in Switzerland CUBA H.E. Dr. E. Camejo-Argudin, Ambassador Extraordinary and Plenipotentiary, Head of the Permanent Mission to the inter national organizations in Geneva CZECHOSLDVAKIA Dr. Otto Benes, Economic Counsellor, Permanent Mission to the European Office of the United Nations DENMARK ecu Mr. N»V. Skak-Nielsen, Minister Plenipotentiary, Permanent Representative to the international organizations in Geneva FINLAND Mr. -

Legation, Mmebre M .J Woulbruon (Belgique), De La Délégation Per- Manneet Belge Auprès Del' ONU Membre M

UNRESTRICTED INTERIM COMMISSION COMMISSION INTERIMAIRE DE ICITO/EC. 2/INF.2 FOR THE INTERNATIONAL L'ORGANISATION INTERNATIONALE 25 August 1948 TRADE ORGANIZATION DU COMMERCE ORIGINAL: ENGLISH Executive Committee Comité Exécutif Second Session Deuxiéme Session LIST OF DELEGATES - LISTE DES DELEGUES Mr. J. A Tonkin, Leader Mr. J. Fletcher Mr. J. Russell Mr. c.L. S. Hewitt Mr.G. Warwick Smith Miss Judith Bearup, Stenographer Miss N. C. Stack, Stenographer Miss Mary Heffer, Stenographer Benelux M. Max Suetens, Ministre Plénipotentiaire et Envoyé Extraordinaire , Président D.r .A. .B Speekenbrink,Directeur Général du Commerce Extérieur, Vice-President Male Professeur .E Devries (territoires néerlandais d'outre-mer), Mmebre M.G. Cassiers (Belgique), Premier Secrétaire de Legation, Mmebre M .J Woulbruon (Belgique), de la Délégation per- manneet belge auprès del' ONU Membre M. Indekeu (Belgique), Ministère des Affaires Etrangères, , Adviser Dr. G. A. L amsvelt, (Netherlands) , Adviser Dr. J. Boehstal, (Netherlands), Secretary Brazil Ambassador Joao Muniz, Chief Delegate Eduardo Lopes Rodrigues, Delegate M. Roberto de Oliveira Campos, Adviser M. Oswaldo Behn Franco, Secretary Miss Maria Ilvà Pinto Ayres, Stenographer Miss Maria José Argollo, Stenographer Canada Hon. L.D. Wilgress, Canadian Ambassador to Switzerland, Chairman Mr. L.E. Couillard, Departrnent of Trade and Commerce Mr. S.S. Reisman, Department of Finance Miss Marion Henson, Secretary to Mr. Wilgress China Dr. Wunsz King, Leader Mr. Chi Chu, Delegate Mr. H.S. Hsu, Adviser Mr. S.M. Kao, Adviser Mr. C.L.. Pang, Secretary Miss Gloria Rosen, Stenographer Colombia Dr. Alfonso Bonilla Gutierrez, Envoy Extraordinary and Minister Plenipotentiary, Senator of the Republic Dr. Camilo de Brigard Silva, Envoy Extraordinary and Minister Plenipotentiary Dr. -

Digital Authoritarianism and the Global Threat to Free Speech Hearing

DIGITAL AUTHORITARIANISM AND THE GLOBAL THREAT TO FREE SPEECH HEARING BEFORE THE CONGRESSIONAL-EXECUTIVE COMMISSION ON CHINA ONE HUNDRED FIFTEENTH CONGRESS SECOND SESSION APRIL 26, 2018 Printed for the use of the Congressional-Executive Commission on China ( Available at www.cecc.gov or www.govinfo.gov U.S. GOVERNMENT PUBLISHING OFFICE 30–233 PDF WASHINGTON : 2018 VerDate Nov 24 2008 12:25 Dec 16, 2018 Jkt 081003 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 5011 Sfmt 5011 C:\USERS\DSHERMAN1\DESKTOP\VONITA TEST.TXT DAVID CONGRESSIONAL-EXECUTIVE COMMISSION ON CHINA LEGISLATIVE BRANCH COMMISSIONERS Senate House MARCO RUBIO, Florida, Chairman CHRIS SMITH, New Jersey, Cochairman TOM COTTON, Arkansas ROBERT PITTENGER, North Carolina STEVE DAINES, Montana RANDY HULTGREN, Illinois JAMES LANKFORD, Oklahoma MARCY KAPTUR, Ohio TODD YOUNG, Indiana TIM WALZ, Minnesota DIANNE FEINSTEIN, California TED LIEU, California JEFF MERKLEY, Oregon GARY PETERS, Michigan ANGUS KING, Maine EXECUTIVE BRANCH COMMISSIONERS Not yet appointed ELYSE B. ANDERSON, Staff Director PAUL B. PROTIC, Deputy Staff Director (ii) VerDate Nov 24 2008 12:25 Dec 16, 2018 Jkt 081003 PO 00000 Frm 00002 Fmt 0486 Sfmt 0486 C:\USERS\DSHERMAN1\DESKTOP\VONITA TEST.TXT DAVID C O N T E N T S STATEMENTS Page Opening Statement of Hon. Marco Rubio, a U.S. Senator from Florida; Chair- man, Congressional-Executive Commission on China ...................................... 1 Statement of Hon. Christopher Smith, a U.S. Representative from New Jer- sey; Cochairman, Congressional-Executive Commission on China .................. 4 Cook, Sarah, Senior Research Analyst for East Asia and Editor, China Media Bulletin, Freedom House ..................................................................................... 6 Hamilton, Clive, Professor of Public Ethics, Charles Sturt University (Aus- tralia) and author, ‘‘Silent Invasion: China’s Influence in Australia’’ ............ -

MADE in HOLLYWOOD, CENSORED by BEIJING the U.S

MADE IN HOLLYWOOD, CENSORED BY BEIJING The U.S. Film Industry and Chinese Government Influence Made in Hollywood, Censored by Beijing: The U.S. Film Industry and Chinese Government Influence 1 MADE IN HOLLYWOOD, CENSORED BY BEIJING The U.S. Film Industry and Chinese Government Influence TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY I. INTRODUCTION 1 REPORT METHODOLOGY 5 PART I: HOW (AND WHY) BEIJING IS 6 ABLE TO INFLUENCE HOLLYWOOD PART II: THE WAY THIS INFLUENCE PLAYS OUT 20 PART III: ENTERING THE CHINESE MARKET 33 PART IV: LOOKING TOWARD SOLUTIONS 43 RECOMMENDATIONS 47 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS 53 ENDNOTES 54 Made in Hollywood, Censored by Beijing: The U.S. Film Industry and Chinese Government Influence MADE IN HOLLYWOOD, CENSORED BY BEIJING EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ade in Hollywood, Censored by Beijing system is inconsistent with international norms of Mdescribes the ways in which the Chinese artistic freedom. government and its ruling Chinese Communist There are countless stories to be told about China, Party successfully influence Hollywood films, and those that are non-controversial from Beijing’s warns how this type of influence has increasingly perspective are no less valid. But there are also become normalized in Hollywood, and explains stories to be told about the ongoing crimes against the implications of this influence on freedom of humanity in Xinjiang, the ongoing struggle of Tibetans expression and on the types of stories that global to maintain their language and culture in the face of audiences are exposed to on the big screen. both societal changes and government policy, the Hollywood is one of the world’s most significant prodemocracy movement in Hong Kong, and honest, storytelling centers, a cinematic powerhouse whose everyday stories about how government policies movies are watched by millions across the globe. -

A Recognitive Theory of Identity and the Structuring of Public Space

A RECOGNITIVE THEORY OF IDENTITY AND THE STRUCTURING OF PUBLIC SPACE Benjamin Carpenter [email protected] Doctoral Thesis University of East Anglia School of Politics, Philosophy, Language and Communication Studies September 2020 This copy of the thesis has been supplied on condition that anyone who consults it is understood to recognise that its copyright rests with the author and that use of any information derived there from must be in accordance with current UK Copyright Law. In addition, any quotation or extract must include full attribution. ABSTRACT This thesis presents a theory of the self as produced through processes of recognition that unfold and are conditioned by public, political spaces. My account stresses the dynamic and continuous processes of identity formation, understanding the self as continually composed through intersubjective processes of recognition that unfold within and are conditioned by the public spaces wherein subjects appear before one another. My theory of the self informs a critique of contemporary identity politics, understanding the justice sought by such politics as hampered by identity enclosure. In contrast to my understanding of the self, the self of identity enclosure is understood as a series of connecting, philosophical pathologies that replicate conditions of oppression through their ontological, epistemological, and phenomenological positions on the self and political space. The politics of enclosure hinge upon a presumptive fixity, understanding the self as abstracted from political spaces of appearance, as a factic entity that is simply given once and for all. Beginning with Hegel's account of identity as recognised, I stress the phenomenological dimensions of recognition, using these to demonstrate how recognition requires a fundamental break from the fixity and rigidity often displayed within the politics of enclosure. -

Movies and Mental Illness Using Films to Understand Psychopathology 3Rd Revised and Expanded Edition 2010, Xii + 340 Pages ISBN: 978-0-88937-371-6, US $49.00

New Resources for Clinicians Visit www.hogrefe.com for • Free sample chapters • Full tables of contents • Secure online ordering • Examination copies for teachers • Many other titles available Danny Wedding, Mary Ann Boyd, Ryan M. Niemiec NEW EDITION! Movies and Mental Illness Using Films to Understand Psychopathology 3rd revised and expanded edition 2010, xii + 340 pages ISBN: 978-0-88937-371-6, US $49.00 The popular and critically acclaimed teaching tool - movies as an aid to learning about mental illness - has just got even better! Now with even more practical features and expanded contents: full film index, “Authors’ Picks”, sample syllabus, more international films. Films are a powerful medium for teaching students of psychology, social work, medicine, nursing, counseling, and even literature or media studies about mental illness and psychopathology. Movies and Mental Illness, now available in an updated edition, has established a great reputation as an enjoyable and highly memorable supplementary teaching tool for abnormal psychology classes. Written by experienced clinicians and teachers, who are themselves movie aficionados, this book is superb not just for psychology or media studies classes, but also for anyone interested in the portrayal of mental health issues in movies. The core clinical chapters each use a fabricated case history and Mini-Mental State Examination along with synopses and scenes from one or two specific, often well-known “A classic resource and an authoritative guide… Like the very movies it films to explain, teach, and encourage discussion recommends, [this book] is a powerful medium for teaching students, about the most important disorders encountered in engaging patients, and educating the public.